A few years ago, I had the good fortune to discuss Green for Danger with two other bloggers: John Norris of Pretty Sinister Books and Ben Randall of The Green Capsule. Here is that conversation, where you’ll discover that the idea I had to revisit all of Christianna Brand’s mysteries is a lot older than even I remembered. It was a pleasure to talk about this favorite book of ours with these esteemed friends, and it’s a pleasure to revisit and Re-Brand her most famous novel.

The richest biographical material that I can find about Christianna Brand comes from Tony Medawar in his preface to The Spotted Cat, Crippen & Landru’s 2002 collection of Inspector Cockrill short stories. But even Mr. Medawar skips over the three-year period between the appearance of her first two novels in 1941 and the masterpiece she published in 1944. Perhaps the war raging throughout England or the raising of her family had slowed her writing down. Or maybe Brand decided to take a more measured approach to getting her new novel down on paper.

Part of the inspiration for Green for Danger may have come from her husband’s experience in 1939-40 working in a military hospital in south London. The author also found herself frequently seeking shelter from the frequent bombing raids: Medawar relates a story Brand told of hunkering down in an air-raid shelter in 1941:

“As I watched, a stretcher was carried carefully down across a pile of crazy rubbish, rafters bricks, furniture, the height of a house – and indeed had one spin two houses – and laid down on the road. I realize now that, as nobody went near it, or attended to the white figure on it, the body must’ve been that of a corpse; it looked ominously short and stumpy. Terrible things happen in an explosion.”

Heads You Lose, which was published after this traumatic event, only pays lip service to the war (“If you say, ‘Is it an air raid?’ I shall scream!”). But Green for Danger is a mystery about the war, of the bombs dropping without warning and decimating villages, and the various services into which ordinary citizens were drafted as part of the battle against Hitler. The setting here is a military hospital in Kent, where we bear witness not only to the tireless courage of the doctors and nurses but also the steps they take to mitigate the grim toll of the work on their lives: the gay parties and amateur talent shows, the gentle flirting between nurses and patients, the more intense, doomed affairs between staff members.

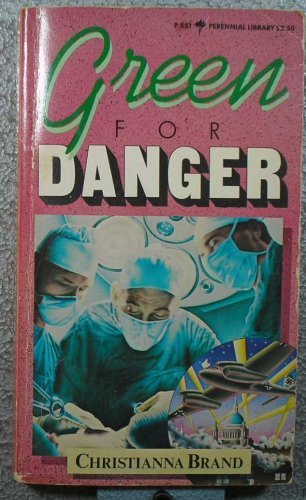

Green for Danger is a novel of war, a workplace mystery, and a gripping domestic drama. Its strengths were recognized almost immediately by the British film industry: the book was adapted to film in1946 and is now recognized as one of the best classic mystery films of all time. It made Green for Danger Brand’s most famous book, an honor it certainly deserves, for it is a wonderful mystery.

The opening chapter introduces us to the dramatis personae as local postman Joseph Higgins delivers seven letters to the military hospital at Heron’s Park, a few miles outside a village in Kent, to announce the arrival of additional staff. In a short space, Brand paints an incisive portrait of each member of the medical team that comprises the main cast. There are the doctors: top surgeon and louche ladies’ man Gervase Eden; earnest and ugly anesthesiologist Dr. Barnes, who is suffering rumors around the death of a patient under his care; and kindly old Dr. Moon, still haunted by the fifteen-year-old death of his only son. And there are the nurses, Marion Bates, the man-hungry theatre sister, Esther Sanson, seeking to escape the confines of a fretful hypochondriac of a mother; Frederica Linley, on a similar mission now that her dad has married a “blowsy trollop of fifty;” and heavy, jolly Jane Woods who dreams of being a dress designer. (In a nod to Death in High Heels, we are told that Woods sends designs to our old friend, Mr. Cecil at Christophe et Cie, who mails her a few quid and calls the drawings his own.)

A year passes, and the lives of these seven strangers thrown together by wartime terrors now resembles a week’s worth of General Hospital: Eden has broken the vengeful heart of Sister Bates, flirted with Woods, and is about to tear apart the betrothment between Dr. Barnes and Fredi Linley, while Esther is consumed by grief and guilt over the death of her mother, whose dire warnings that she would be killed by bombs if Esther left her to work have come true. As the victims of the most recent air raid come pouring in and the stress level rises, one wouldn’t be surprised to find Dr. Eden lying dead in the operating theatre with a scalpel in his chest!

But death, when it comes, strikes nobody in the circle; instead, a patient with a leg injury that is not very serious ends up dying on the operating table. The cause of death is not apparent, and the victim – who turns out to be our old friend, the mailman – hadn’t an enemy in the world. Fortunately, Dr. Moon has an old friend who happens to be “the high ding-a-ding” at the police station in Torrington. If Inspector Cockrill can’t clear the whole matter up, who can?

That is exactly what Cockie intends to do – “Just another anesthetic death. You doctors slay them off in their thousands” – and he hopes to grab a free lunch, interview the widow and staff, sign off on an accidental death and be home before the blackout. But things are about to get a lot more complicated: a figure masked in surgery garb was seen taking the key to the operating theatre the previous night, and yet nobody in the hospital admits to being that person. It’s just the kind of niggling fact that will lead to more intrigue . . . and another death.

As we have already seen, Brand creates well-drawn and sympathetic characters using charming prose and well-crafted dialogue. Her pages teem with good humor and sharply etched observations of the world, as when Cockie is questioning Fredi Linley early on and professes surprise at the all-too-human goings on of the medical staff. Fredi replies:

“People are – just people, aren’t they, wherever you go? I mean, I look upon detectives as superhuman creatures who press buttons and waffle about with a little gray fingerprint powder for a bit, and have their case all solves in half a minute; but I suppose you’re really just ordinary people with worries about having a clean collar and eating your breakfast too quickly and things like that, and so are we.”

Moments like these are a reminder of the changes being wrought in classic detective fiction: the humanizing of the sleuth and the suspects and the emphasis tipping away from pure puzzle and more toward psychology and emotion. Brand was at the forefront of this change and became one of the best of its early purveyors.

And yet, what Green for Danger has that can’t quite be said for her first two novels is a beautifully wrought puzzle, containing clues, a fascinating method for murder, a second murder that is as gripping and dramatic as the first in a totally different way (and it’s not just padding), and some moments that I think rival Christie in their cleverness. One of the most effective examples of this is in the way Brand uncovers motive. There are overt examples: Higgins had overheard all the romantic hijinks going on in the ward; he had also threatened to make trouble for Dr. Barnes by spreading the news that he had killed a girl on the operating table before the war. Additionally Brand invites her readers to speculate – whose voice did Higgins recognize just before his surgery, and from where? – and to jump to conclusions, as when Major Moon tells the story of the unpunished bicyclist responsible for his young son’s death (“I knew who the man was, but – I couldn’t do anything; there was no proof.”) and we are left to wonder if a certain bicycle-riding mailman couldn’t have been responsible.

True to her style, Brand invests as much time exploring the pain wrought upon a close circle of suspects by fear and suspicion as she does on the investigation. Even the murderer is not immune from this growing panic: two more people are nearly killed before Cockerill unmasks a surprising killer, a clever method, and a motive that feels as inevitable as it is tragic.

Three books into this project, and I’m dead sure as to why Christianna Brand appeals to this reader. Fond as I am of a clever puzzle, I am deeply drawn to a story that contains a powerful emotional pull and a gut punch at the end. This may help you understand why I am drawn to Agatha Christie’s 40’s mysteries and Ellery Queen’s Third period (especially Calamity Town and Cat of Many Tails), even though their puzzle aspects can pale beside their 1930’s work. It’s why I love John Dickson Carr’s He Who Whispers and She Died a Lady, which aren’t nearly as complex as, say, The Three Coffins – you feel something at the end of this pair of mysteries that you won’t feel no matter how long you hang out on Cagliostro Street!

And yet . . . the puzzle itself isn’t merely gravy for me; otherwise, I’d be reading a lot more modern crime fiction, wallowing in despair and wondering if these authors ever used order and method to plan their books, why they confuse “closed circles” with “locked rooms” (Ruth Ware did this while referencing her own work in an interview just the other day), and why nobody can come up with a clever clue.

There are clues aplenty in Green for Danger. For the first time in her work, Brand strikes a fine balance between logic and feeling. In the end, one finds oneself heaving a sigh of gratitude for a well-crafted mystery, but there is also a clutch at the heart as we realize that the little circle of medical personnel at Heron’s Park will not soon be forgotten.

* * S P O I L E R S * *

“The old man stirred and groaned, ‘Bombs! Bombs! The bombs!’

”’No bombs,’ said Esther reassuringly. ‘Only guns; not bombs.’

“He lost even his feeble interest in the bombs. ‘The pain!’

“’Just bear it for a little bit longer,’ she said, her hand on his wrist. ‘Just while I get your clothes off and clean you up a little bit; and then you shall go off to sleep and forget all about it.’

“Standing with the basin balanced on her hip, towels over her arm, she looked down at him pityingly. Poor old boy; poor, frightened, broken, pitiful little old man . . . She rung out a piece of gauze in the hot water, and began gently to wash his face.”

One of my favorite types of trickery in classic mysteries is the Trick of Omission. The author gives us certain information and invites us to jump to conclusions. The doctor bidding leave of his friend in the study, the young couple at a fancy restaurant innocently celebrating their betrothment, the girl coming upon a dead body and then staring at her own face in a mirror as her mouth forms a scream. Of course these examples are all Christie, for she excels at this bit of flummery. Who notices the oddity of Dr. Sheppard’s phrasing, or questions if the couple have the same innocence when we next meet them, or wonders whether the girl is truly in shock or if she’s deliberately fixing that appearance of shock on her face.

Whatever the situation, it serves to push suspicion away from a killer (or two), and the above passage early in Green for Danger does the same. We don’t see Esther wipe the dirt away from Higgins’ face and recognize him as one of the local crew who failed to rescue her mother. We are drawn to Esther in sympathy – and because Inspector Cockrill knows her and is fond of her, and because Major Moon dotes on her, and because she has a sweet romance brewing with one of her patients. She’s not pretty and cold like Fredi or quick-witted and brave like Woods. And so we like her and excuse the fragility that turns her into a murderer.

Esther is a good person stricken mad by grief and guilt, but it’s not the unsatisfying insanity with which we were presented at the end of Heads You Lose. As Cockie himself explains, “The murderer is not a lunatic. I think he has what they call an idee fixe on just one subject but in everything else he’s as sane as – as you or me.” Esther’s concern for the others throughout the investigation is genuine, as is the love that blooms between her and the handsome brewer William. In fact, Brand doubles down on Esther’s tragedy, first by having her shoulder – quite unreasonably – the blame for her mother’s death, and then by finally allowing herself to fall in love, only to learn that William was part of the same rescue team as Higgins.

In the end, Cockrill laments at having to bring in the daughter of an old friend for murder, but it is her circle of friends who give Esther the peace she needs. Esther’s death provides a fascinating coda to Cockie’s journey here: after tenderly explaining the how and why of her actions, he reacts with horror at her suicide and frantically tries to revive her in order to face trial and possible execution. Meanwhile, her friends bid her a loving and sad farewell and fend off Cockie’s accusations by pointing out the part he unwittingly played in her death.

In a few weeks, my friends Jim Noy and Moira Redmond and I will be discussing another book that came out this same year: Agatha Christie’s Towards Zero. It’s a book strong on both characterization and clueing, and I like it very much. And yet, there is not a sign of war going on in the country (Christie was good at holding the war at bay when she chose to), and while in retrospect we might feel a tinge of sadness that this is the last time we will come upon Superintendent Battle, we don’t leave the circle at Gull’s Point feeling much about anyone else. The killer is caught, and everybody pairs up neatly and goes off to live happily ever after, forgetting that this lunatic once dwelled in their midst, savagely beat their hostess and friend to death, and tried to frame an innocent person for their crime. No muss, no fuss.

On the other hand, Green for Danger reaches its conclusion and leaves us shattered. The tight circle of wartime co-workers breaks apart. One romance might survive, another certainly has no chance . . . and everyone must go back to their lives haunted by Esther’s tragedy and what it cost all of them, not least the murderer herself.

“Laughing and talking they strolled on up the hill, and if the ghost of an old man toiled ahead of them, carrying in his hand a letter signed with the name of his own murderer – they did not notice him.”

I am not denying the emotional punch of Brand’s works, or the stronger characterization of the 40’s works of Carr, Christie, and Queen. But I think it’s a facile assumption— and an error at that— that the puzzles of this period “pale” besides those same authors puzzles of the 30’s. Yes, the puzzle plot of Five Little Pigs is not as COMPLEX as that of, say, Death on the Nile or Peril at End House. But that does mean that the puzzles— even just as puzzles— are INFERIOR. For instance, I’d say the puzzle aspect of FLP is superior to that of those earlier Christie works, even shorn of its superior characterization— superior by rights of its structure, in which deception is born of natural motivations of the characters (which would have worked even if, say, Amyas had been characterized superficially as the stocked artist devoted to his art). The non-culprit complicity and deceptions of both Amyas and Caroline is brilliantly designed, and would work even if those characters were not nearly as beautifully rendered as they are. Yeah, I recognize the flaws of FLP’s plot, but I think it’s basic structure vastly outweighs them (and I’ve yet to find a GAD puzzle yet free of plot flaws… which I don’t think should be denied or overlooked, but can be outweighed by strengths).

Likewise I’d prefer the plot of He Who Whispers (except for its one problematic coincidence) better than that of The Hollow Man, even if it didn’t have better characterization as well. I admittedly can’t say the puzzle of Calamity Town holds up better for me than that of The Siamese Twins Mystery, but Cat of Many Tails’s does. The 30’s works are by and large significantly more complex in their puzzles. But I don’t think that they’re at all more consistently better puzzles, even if the quality of characterization is not taken into account. The error, I believe, is in mistaking density of clueing for superiority of clueing. One great clue can have more value than five weak ones. Indeed, for most of these authors I belief the 40’s afforded their best work in both characterization AND puzzle.

I also think I perhaps see the emotional impact of the end of Green for Danger differently than you do (I say perhaps because I’m far from certain of this). It is very powerful for me, but having little to do with the the tragedy of Joseph Huggins, Esther Samson, or Major Moon. For me it is all about that twinge of pain following hope for Jane Woods. A tiny, unnoticed, everyday tragedy, but one that is so related to every one of our lives.

Incidentally, I have more background info on Brand and Green for Danger, from her EQMM interview, and all the supplementary appendices in the University of San Diego edition of GFD, which is be glad to share with you if you’d like.

LikeLiked by 2 people

*stock

LikeLike

I did not mean to suggest that the puzzles were worse, only simpler. It’s more of an issue with Calamity Town than the other titles to which I alluded, but CT is a perfect example of a book where even though the murderer is obvious from nearly the start, it doesn’t stop me from enjoying the book a whole lot. I would venture to say, though, that many of my blogging friends disagree and find the “simplified” puzzle disappointing . . . or they don’t find the higher emotional quotient a worthy substitute.

I didn’t get into detail about Woody, although I alluded to the relationship that “has no chance.” Gervase delivers his “it’s not you, it’s me” speech, and Woods smiles through it. The moment is devastating.

As for the extra biographical info . . . . yes, yes, YES please! As soon as you can!!! 🙂

LikeLike

But there again, it sounds like a discussion of compensating for weaker puzzles with stronger characterization, and that’s not at all what I’m taking about. Calamity Town is not a good example for me because it IS a weak puzzle, at least in my estimation (it has both major credibility problems [who is going to write all those letters in advance?] and it’s also transparent [due to the Peril at End House tradition, the culprit is not a character outside of reader suspicion). But people speak of Five Little Pigs and He Who Whispers as if they more than make up for their slightly weaker plots with superior atmosphere and characterization. But I say that their plots— just as plots— are superior to the earlier works they are held up against. Indeed, I think that He Who Whispers and Five Little Pigs would have to be deemed as superior plots to the likes of The Hollow Man and The ABC Murders even if their characterization were lousy!!

◦ Take Five Little Pigs. It has excellent deception (primarily based on the coinciding, non-maleficent deceptions of Amyas and Caroline, in turn based on extremely different but thoroughly understandable and supported motivations), and compelling clueing (the location of fingerprints, Angela’s pranks, “Everything tastes foul today,” etc…). The ABC Murders, on the other hand, has an excellent basic central deception (just a reworking of The Sign on the Cross, but still solid), but practically no significant clueing (indeed, I believe Chesterton’s short story version provides much more).

Likewise, I think that After the Funeral is not only better characterized than The Mysterious Affair at Styles, I think it has a better plot! Not more complex, mind you, but still better, regardless of relative merits in characterization. So this is not a matter of compensation for me.

LikeLike

There are a lot of errors and typos in the above, but none that I think would keep anyone from understanding what I was trying to say. Still, I think it’s important to point out that I meant to refer to Chesterton’s The Sign of the Broken Sword, not the 1932 Paramount film The Sign of the Cross. Sheesh! I swear I haven’t been drinking.

LikeLike

Really enjoyed your post Brad though I have not read all of Brand’s mysteries – this is definitely this us my favourite thus far (I liked CAT AND MOUSE but it is such a different type of book that …). Great to see the still from the movie as I really love that adaptation – there are only a small number of films that really succeed in transporting a classic detective novel faithfully and successfully to the screen but this really is a superb example of when that works. I would add the original film of THE THIN MAN, THE KENNEL MURDER CASE, Clair’s AND THEN THERE WERE NONE, Dmytryk’s FAREWELL, MY LOVELY, both Del Ruth’s and Huston’s versions of THE MALTESE FALCON and maybe THE BLACK CAMEL with Warner Oland … but that’s a whole different conversation 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

PS As ever, apologies for the typos.

LikeLike

There are so few films out there that say, “Let’s assume that our audience is intelligent, that they can handle the delivery of visual, aural, and all manner of clues as they pass before the screen, that there is a way to deliver a complex literary puzzle in another medium and be successful in delivering our message”. Green for Danger is such a film (although it cuts one of the book’s suspects out and cheats us out of much of the drama as a result). So is The Kennel Murder Case. So are a handful of others. I’m a big fan of the Charlie Chan films, but only a few of them had the multiple clues combined with intrigue to vie for a “best of” list; by the time they got to Sidney Toler, we usually got one good “giveaway” clue (the one in Charlie Chan in Panama is my favorite). The same thing happened with the Thin Man movies – although the last few really were a shadow of the first three.

If he can put down the booze for a minute, Scott K. Ratner will trot out his list of the best. Not all of them are easy to get a hold of, but if between the two of you we can get links to every one of them posted here, I will admit to SKR that there is no such thing as “fair play.”

Maybe . . .

LikeLike

Yeah, I’d say there are several others out there, some very hard to access, including (or, I should say, especially) LOVE LETTERS OF A STAR (1936), THE NURSEMAID WHO DISAPPEARED (1939), THE NIGHT CLUB LADY (1932), and a few others. I’d also include THE VERDICT (1946) and DEATH ON THE NILE (1978), that are obviously far more accessible, but their merits are less unanimously agreed upon. LOVE LETTERS OF A STAR has been shown twice in film festivals in the last decade, and I had to take a trip to the BFI to watch a personal viewer (like an editing machine) copy of THE NURSEMAID WHO DISAPPEARED. But both were well worth the effort (but I do have crappy copies of THE NIGHT CLUB LADY, DEATH IN HIGH HEELS, and several other interesting whodunit film obscurities for those with interest. And some of them based on plays [AFFAIRS OF A GENTLEMAN, CRIME ON THE HILL, NIGHT OF THE PARTY] I rate as just as interesting).

And then there are films like THE WESTLAND CASE (1937) which do well by the puzzle plotting of their source novel, but are not particularly cinematic. Even more so with THE DARK HOUR (1936), the extreme fidelity to its source novel somewhat obscured by the turgid, uncinematic presentation probably entirely attributable to its budget.

But even those that are most highly praised are sometimes a mixed lot. For instance, THE THIN MAN— one of my favorite films, mind you— I’d rate as both tremendously successfully (in conveying the warmth and humor of its leading characters) and a total failure (at communicating Hammett’s critical point about the artificial symmetry of GAD). And rather than just omit the latter, it leaves in all the exposition without ever explaining it, so that we have a lot of unnecessary and largely unentertaining footage to sit and wait through (if you don’t believe me, just try to watch the film, skipping everything involving Nick and Nora, and ask yourself how popular that film would’ve been with audiences… but also notice how much film is still there!).

The same might even be said of GREEN FOR DANGER, which I believe both loses and gains in adaptation, even merely in plotting alone. There are some lovely clues left out (the color of the bicycle, the restlessness of the patients), but at least one nice one added in (the salvage bins). And while placing the revelation of method and culprit together at the end is a much more conventional structure than Brand’s several-chapter separation (which recalls several Carrs to me), I’d say it’s probably also more effective. That is, another example of the cliche becoming such because the convention works so well. It’s a trade off, I’d say.

And as for the truth regarding “fair play,” well, the truth of the matter is fortunately not dependent upon our acceptance of it. Or, as Leo Genn says in the film in question, “The truth is no less true for being brutal.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post, Brad. Green For Danger is my favorite of the Brand books I have read so far and for all the reasons that you included in this review. I really do owe it another read because I found Brand’s multiple-perspective style rather jarring on the first read, but even then I loved the simple cleverness of the puzzle and the richness of the hospital atmosphere. Not until Shroud for a Nightingale (a book I LOVE) have I felt that a similar setting has been rendered so well.

Seeing as you hinted toward them, I look forward to your thoughts on Towards Zero . I read it some months ago and found it just as good as it was when I read it the first time. An overlooked Christie gem if you ask me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

SfaN is one of my top three James novels, but as I recall the motive came out of nowhere. What I love about GfD is how the facts you need to know get woven into the text from the start. Have you read Tour de Force? It’s another favorite Brand, although it’s more, er, controversial.

Towards Zero has always been a favorite, but there are a few glitches that come about whenever one reads a mystery six times! I look forward to that conversation,

LikeLike

On the subject of Tour de Force and its controversy, I really think that I liked it so much when I read it and afterwards because I knew the ending. When Re-Branding reaches TdF I’ll come back to go in spoilery detail about that experience…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I acquired the BL reprint of this recently, and am looking forward to rereading it with a better sense of what to expect. I first read it being assured that she was Christie’s equal and came away somewhat nonplussed — the characters were good, but in my memory the plot has nothing like the rigour or clewing that others assure me are there.

So here’s to yet another second reading of something that completely reverses my original stance. One of these days I might pay attention to a book first time around…

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re going to love it the second time: I have it in authority that before she wrote it, and in order to up her game, Brand consulted Ellery Queen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I heard it was actually Leonard Gribble she consulted…

LikeLike

BTW, does “It made Green for Danger Brand’s most famous book, an honor it certainly deserves, for it is a wonderful mystery” mean that it deserves to be her most famous book, or merely that it deserves great fame? Because I taste issue with the former…

LikeLike

I meant the latter. Now shut up. 😘

LikeLike

The irony is that many of those involved with the finest whodunit films seem to have had very little interest in the genre (Sondheim, Shaffer, and Rian Johnson aside) or their source works. In the case of GREEN FOR DANGER we have Sidney Gilliat:

“The novel, by Christianne Brand, had not been recommended as film material by the story department of the Rank Organisation and I bought a copy at Victoria Station just to while away a journey. I was attracted not by the detective, Inspector Cockrill, who, though by no means as dull a plodder as Inspector French, did not exhibit very much in the way of elan; nor particularly by the hospital setting, then still held by many distributors and exhibitors to be death at the box-office. No, what appealed to me was the Anaesthetics—the rhythmic ritual, from wheeling the patient out to putting him out and keeping him out (in this case permanently)—with all those cross-cutting opportunities offered by flow-meters, hissing gas cylinders, palpitating rubber bags and all the other trappings, in the middle of the Blitz, too. As for that unfortunate whodunit element, I largely informed myself and my collaborator Claud Gurney, we would lose it altogether or at the least reduce its importance. But Miss Brand had integrated her story far too well, and in the end we had to change tack and—on the principle, one supposes, of if you can’t beat ’em join ’em—deliberately make capital of the very cliches of the detective novel, in the course of which Cockrill turned into the spritely conceited extrovert of the film with a dash of mild sadism and a decided tendency to jump to the wrong conclusion; and incidentally became the narrator.”

And even less kindly from Rosalind John (Nurse Sanson):

“Alastair Sim was wonderful in that film, which was quite a success – – surprising given the frightful novel from which it came!”

LikeLike

Gillian is definitely in part setting out go guy the whodunit. I also thought he did a great job with ENDLESS NIGHT. It

LikeLike

“Gilliat” that was, before auto correct (pronounced with a hard G by the way). Not sure I thought the 39 version of NURSEMAID was much of a flick (less fun but more faithful than the Van Johnsin version, admittedly) – I much prefer the film of RYNOX (which I also first saw on a Steenbeck in the basement of the BFI, where I used to work).

LikeLike

Really!? I feel much differently. I found THE NURSEMAID WHO DISAPPEARED both more faithful AND more entertaining than 23 PACES TO BAKER STREET (the ‘39 film has the bracing feel to me of a late British Hitchcock film like THE LADY VANISHES, the later film doesn’t, though it’s clearly trying to capitalize on the success of REAR WINDOW). As for RYNOX, a print leaked out on the internet soon after its rediscovery. I’m a big Michael Powell fan (A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH is my third favorite all-time film, following TROUBLE IN PARADISE and the Clair AND THEN THERE WERE NONE), but I found RYNOX rather primitive and uncinematic.

In a certain sense, my favorite Philip MacDonald adaptation is MENACE, the 1934 Paramount adaptation of his R.I.P. it’s not a total success, but it has one of my favorite premises, and one of the reasons that Death of Jezebel is my favorite mystery novel is that it provides a satisfying solution to the nearly identical set-up that neither R.I.P. nor MENACE pulls off (and adds a great impossible crime in doing so).

I wish I liked the Gilliatb ENDLESS NIGHT more. It’s got some good stuff in it, but I feel both Hywel Bennett and Per Oscarsson are rather badly miscast, and I find the house ugly.

LikeLike

In fairness, despite my poor typing (as ever, 1000 apologies), fairly sure I said 23 PACES is clearly less faithful (though I have always liked it, not least for its wacky sense of London geography). I was going purely for decent movies that were also close to the source novel – RYNOX is very small beer in the Powell filmography but is very faithful and lots of fun. I still think Dearden’s SECRET PARTNER is an uncredited remake 😁 BTW the Jean Gabin version of MAIGRET SETS A TRAP is another I would put on the list. And PSYCHO …

LikeLike

Ah, I was thinking less of films that were faithful and also good movies, but rather films that are good whodunits and also good movies. After all, I’d hardly refer to the ‘45 And Then There Were None as particularly faithful to its source (either the novel or the play), but it’s both an excellent whodunit and an excellent film. That a film like THE KENNEL MURDER CASE is also faithful

to its source is rather coincidental in my opinion, as some of the best moments in adaptations, IMO, have been when they’ve been least faithful (and some of the best films overall have been among the least faithful adaptations— while Kennel is my favorite Vance film, for instance, my second favorite is Benson, which is the least faithful Vance film until the late 1940’s).

Then again, LOVE LETTERS OF A STAR is very faithful AND very good…

LikeLike

ROSAMUND John! Jeez! When will I ever proofread before posting?

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is one important question we need to ask. Was the greater emotional complexity and stronger characterisation in detective fiction from the 1940s onwards really a good thing, or was it a mistake? To my way of thinking it represented a giant step backwards, a step backwards into the mid-19th century.

It represented an abandonment of the very things that made the detective fiction of the golden age so exciting. The lack of emotional depth and the thin characterisation of 1920s-1930s were features, not bugs.

The move toward emotional depth in detective fiction appealed to people with a very traditional very conservative view of literature. It made detective fiction seem more like “proper” literature, which for a lot of people meant the 19th century novel.

LikeLike

Unlike surprise and inevitability, which are inherently in opposition (thus the aim of puzzle plot fiction to perfectly balance these two elements) I don’t see characterization and puzzle as being opposing elements. It’s true that the rise in emphasis on characterization has historically coincided with a gradual abandonment in interest in puzzle, but I see no reason why that need necessarily be the case. Certainly richness of characterization can aid the mechanics of a puzzle, and the mystery inherent in puzzle can add fascination to characters. And just because some Golden Age puzzles were thin in characterization didn’t guarantee that their puzzles were strong— there are some lousy puzzles that are poorly characterized. Likewise, later novels with thin or nearly absent puzzles weren’t necessarily well characterized. Unlike surprise and inevitability, they don’t function as yin and yang. It is possible to be strong in both.

LikeLike

I don’t see characterization and puzzle as being opposing elements.

I think that the increasing emphasis on emotion and characterisation inevitably led to the decline in the quality of plotting. Publishers started increasingly to publish crime novels by writers who were strong at characterisation but incompetent when it came to plotting. Critics started giving negative reviews to well-plotted books and over-praised “psychological” crime novels.

Inevitably writers started to neglect plotting in favour of characterisation.

And most of the new breed of crime fiction ended up being second-rate detective stories and second-rate psychological novels. Most writers are not all-round geniuses who are equally strong at plotting and characterisation. Most writers are good at one thing. Gradually the writers whose strength was their plotting became marginalised.

It’s like trying to design a car that combines all the best features of a sports car and a pick-up truck and a station wagon. You end up with a vehicle that is equally useless as a sports car, a pick-up truck and a station wagon. If you want a sports car, buy a sports car. If you want a pick-up truck, buy a pick-up truck.

LikeLike

What I really object to is the widespread assumption that a “good” novel has to be about characterisation and emotional complexity, so therefore 1920s/1930s GAD fiction is “bad” fiction because it’s tightly focused on plot. And BTW, I’m not accusing anyone here of subscribing to such views.

It’s a terribly old-fashioned traditionalist view of literature, hopelessly stuck in the mid-19th century.

What was exciting and fresh about detective fiction in the 20s and 30s was that it rejected such outdated views. Literature could be about characterisation but it didn’t need to be. There was room for new genres like detective fiction and science fiction that had their own rules and conventions and did not feel compelled to conform to 19th century views of what a novel should be.

LikeLike

I too object to that notion that a “good” novel has to be about characterization and emotional complexity, and the fact that puzzle quality ultimately declined in detective fiction as emphasis in character rose is undeniable. But I don’t see these changes necessarily as a logically function of each other.

For, I believe we CAN have the best of all possible worlds… we just can’t have the MOST of all possible worlds. For me, the film Casablanca (which I like a lot) offers a healthy demonstration of this. The screenplay of Casablanca did not have to suffer in quality because of the excellence in acting, and the level of wit in it was not weakened by the quality of the music score or the gleaming cinematography. The film couldn’t be entirely about any one of them, but all of them could be excellent. Indeed, the excellence in the individual elements may have enhanced our appreciation of all the others.

Now admittedly, a greater emphasis on detective story characterization does necessitate a diminished emphasis on puzzle, but it certainly doesn’t necessitate a diminished QUALITY of puzzle. As far as I’m concerned, Death of Jezebel is superior both in puzzle and characterization to Peril at End House. Is it quite as much about puzzle as the earlier Christie work? No, but just because a bit less of the verbiage is dedicated to puzzle doesn’t make it an inferior puzzle, and I believe the superior characterization of the Brand novel actuallt added some brilliant nuance to the deceptive qualities of the puzzle aspect. Again, I don’t believe these elements are necessarily working in opposition, as many of the finest detective stories of the late Golden Age demonstrate.

People began to believe that characterization was paramount and puzzle was cheap, but people didn’t start to believe the puzzle was cheap BECAUSE characterization improved. I’ll agree it was snobby propaganda that ended what we love about the Golden Age, but the improvement of characterization was not at fault. It was rather the idea that excellence in one area inherently means the lack of it in another. As if snobbish film theorists were decrying the wit of Casablanca, saying that it cheapened the photography.

LikeLike

But if publishers decide they want to publish lots of character-driven crime novels that inevitably means fewer puzzle-plot mysteries being published. Just as if movie studios decide they want lots of Marvel comic-book movies that means fewer movies of other types get made.

And I personally don’t think that stronger characterisation in detective stories is a good thing. It inevitably shifts the focus away from plot because all the character stuff slows down and damages a good puzzle plot. It leaves less room in the story for multiple plot twists, otherwise you’ll end up with a book that weighs as much as a house brick. And the longer the book gets the less well it works as a puzzle plot.

You end up with something like CALAMITY TOWN, which fails on every level.

Just as in a movie if you decide you want an extra 30 minutes of gunfights and explosions then other elements will have to be eliminated.

LikeLike

But once again you’re confusing the quantity of an element with its quantity. By this same reasoning, the funniest comedy would be the one with the most jokes, irrespective of the quality of that humor. It just doesn’t work out that way. Though many of the best puzzle plots are indeed highly complex, a more complex puzzle plot is not inherently more satisfying than a less complex one, as is born out by the relative reputations of GAD novels, even among those (myself included) who are primarily interested in the puzzle plot aspect (and even just regarding the puzzle aspect). There are other considerations beyond complexity. The most complex puzzle plot might not be the most effective in its deception, might not be the one offering the greatest sense of retrospective inevitability, and might not be the most credible.

And unlike Boyle’s law of gas pressure, puzzle and characterization are not inversely proportional. It is possible for a work to have both stronger characterization AND a stronger puzzle, because the strength of these elements is not necessarily a function of each other, or of the percentage of words expended upon them. I consider the characterization in Death of Jezebel much stronger than that of The Spanish Cape Mystery… but I also consider its puzzle much (much) stronger as well. How could that be possible if- as you suggest— the strengthening of one necessitates the weakening of another? The Queen novel admittedly devotes a larger percentage of its verbiage to questions of plot, but that doesn’t make its plot more effective (especially regarding the deception axis). And I think it ludicrous to suggest that making that characterization even thinner than it is would have improved the puzzle.

The introduction of Calamity Town as an illustration I consider a straw man tactic. I too think Calamity Town is a lousy puzzle plot. But it’s a lousy puzzle plot because of its lousy puzzle, not because its characterization is strong. If it had weaker characterization it would still be just as weak a puzzle, and possibly even weaker (as characterization can at times be an effective device of plot deception and credibility).

The general shifting of emphasis from plot to characterization over time was no doubt detrimental to the former, I admit, but that’s not at all the same as saying that strength of one element necessarily results in weakness in the other. It was a matter of shifting values, and I share your opinion of it being unfortunate. But there was definitely room in this town— and in any given novel— for both, and the right improvement in characterization could (and at times did) enhance the effectiveness of the puzzle.

LikeLike

I do appreciate the conversation going on between you, d and Scott. D, I disagree with you on many counts, starting with the supposition that the publishing industry drove the change from puzzle-centered to character-driven mysteries. I cannot see Harper Collins calling Agatha Christie and saying, “Please, dear, stop doing all those sensational puzzle msyteries of the 30’s and stick to psychological drama.” All art is dynamic, and the truly great artists do not stick with a formula. Even as the Golden Age began, the founders, like Berkeley and Sayers and, yes, Christie, were chafing to play with formulas and experiment. Every novel by Berkeley was experimental in one way or another. Sayers gave up altogether. Christie jumped back and forth between many forms. Sad Cypress is character-driven, and then Evil Under the Sun focuses more on puzzle – although the characters are much less stick figures than in most of the early-mid 30’s novels.

I think Brand shows that you can have both and do just fine. I think Calamity Town may not be your cup of tea, but I would venture to guess that most Queen fans, myself included, would disagree that it “fails on every level.” It’s a beautiful book, and it is a mystery as well. This does not mean I’m asserting that the character-driven mystery is an improvement on the puzzle; I do think, like Scott, that you can have one or both of these elements and end up with a good or bad book. I do not have much patience with the modern “mystery” novel that has foregone the inclusion of that combination of surprise and inevitability that marks the better mysteries of yesteryear – but there are a number of modern books that do have both and still manage to be more than an homage to the past. Janice Hallett’s The Appeal is such a book.

Of course, plenty of “character-driven” mysteries have done like you said, d: they “inevitably shift the focus away from plot because all the character stuff slows down and damage a good puzzle plot.” But some of my favorite books find the puzzle within the characters and do a great job at both. I think Christie in the 40’s did just that with books like Five Little Pigs, Towards Zero and The Hollow.I think Brand succeeded in doing it as well. An author like Josephine Tey focused much more on character than on puzzle, as we find in Miss Pym Disposes – which I think is a fabulous mystery, despite its emphasis on character over clues.

Obviously, you feel strongly, and I respect your opinion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brad, I agree with all you say there, though I have trouble finding much nystery merit in Calamity Town, and I’m still not seeing any in The Hollow (but again, it’s almost like I’m missing pages fro.pm my copy… though I’ve looked at several copies!).

LikeLike

It’s not so much that I feel strongly about it, but I do feel strongly that the conventional view should always be open to challenge. If the conventional view is that strong characterisation and emotional complexity are good things in any novel my instinct is to ask – why?

And to ask, are they necessarily good things in every genre? Is it possible that in some genres they’re actually bad things?

LikeLike

The more I read of this, Brad, the more I get a sense of why Death of Jezebel might not appeal to you. Though the mystery solution is brilliant (IMO), one doesn’t finish reading it with an emotional gut punch, but rather with an undramatic sense of everyday hopelessness. Nothing horrendous happens to anyone, but no one gets what they want.

LikeLike

I haven’t read it in 30 years. We’ll find out how I feel when I get to it in the fall.

LikeLiked by 1 person

BREAKING: The next book of LRI, DEATH ON BASTILLE DAY by Pierre Siniac will be released this week !

LikeLike

Pingback: RE-BRANDING #4: The Housing Crisis – Suddenly at His Residence | Ah Sweet Mystery!

I’ve just finished reading this for the first time. I enjoyed it greatly, though I felt it got a bit wobbly towards the end. The whodunit element was excellent, the howdunit also great (though I did in fact work it out! But of course it’s revealed early enough that it’s clearly not the puzzle focus), the whydunit fantastic. Great clueing all round, and setting and characters also top-notch. What spoiled it a little for me was the ending. I never felt more sympathy towards Cockrill and less sympathy with what Brand wanted to portray (and what you appear to feel as well). The ending scene was meaningless, since I no longer cared for these characters after what they allowed to happen and gloated about accomplishing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad your first read was enjoyable, Villeic!

“What spoiled it a little for me was the ending. I never felt more sympathy towards Cockrill and less sympathy with what Brand wanted to portray (and what you appear to feel as well).”

What I feel is more complicated: if a body meet a body – and then kill that body – I want the killer to be punished. We sympathize with Esther throughout the book, just as we often sympathize with, or enjoy the presence of, murderers in Christie, Carr, or Queen; that’s part of the trickery of a good murder mystery. But Joseph Higgins is no Mr. Ratchett; neither are Nurse Bates or the cute soldier. They died (or almost died, in the case of the soldier and Freddy) because Esther felt guilty for leaving her mother alone. She deserves whatever punishment she’s got coming to her.

What I love here is the drama of the scene and the fact that these well-meaning people do what they can to put their friend out of her misery. Yes, it’s morally wrong, but it makes for a powerful coda to the solution. If you didn’t like it, I can imagine that the last pages, where all these, oh, let’s call them murderers, go on with their lives, would rankle.

Warning: Brand does stuff like this more than once. She experimented a lot with “alternate” forms of justice. It happens in a different way in the next book, and I liked it less than I like it here. (But then, Green for Danger is a better book.

LikeLike

I feel this kind of ending happens often in detective fiction… Christie did it a bunch. Carr did it a bunch. Crispin has done it too. But since Brand invests everything with such emotion, the complete mismatch between my moral attitude and that of the characters/author hurts more.

That said, Carr’s just as “unconventional” about his endings and I’ve finished at least one of them utterly fuming at the detective.

I think I might have liked the other ending I think you’re referring to more than this one. Could have been the extra excitement of the setting/events. But also in that case the characters weren’t colluding to make it happen, and it was an act of sacrifice as well. Even so, Green For Danger is the better book for sure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve always thought that there was a significant difference between a murder (even a mercy killing) and blocking the intervention of a suicide. I’ve never considered any of the survivors of Green for Danger guilty of much at all.

BTW, Brad, what book are you referring to as “the next book”?

LikeLike

Suddenly at His Residence. Belle OC is correct: nobody is trying to block the killer’s suicide there either, but the circumstances are quite different.

LikeLike

Oh yes— I keep forgetting that Suddenly at His Residence did come AFTER Green for Danger. And yes, I consider Green for Danger a better book.

But what does Cockrill think Major Moon is trying to do with the syringe just before Cockrill knocks it out of his hand? A merciful execution to help her evade legal justice? Because they both seem to be attempting to keep her from dying (one rightfully believing she’s killing herself, and the other miserably believing someone else is killing her mercifully).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brand does stuff like this more than once. She experimented a lot with “alternate” forms of justice.

It is surprising how many GA writers were keenly aware that upholding the law was not necessarily consistent with justice. It’s even more surprising that quite a few GAD writers were prepared to consider the idea that sometimes the law should be actively thwarted.

For me the most disturbing case is Nicholas Blake’s <iHead of a Traveller in which Blake/Day-Lewis seems to be seriously suggesting that artists and intellectuals should be above the law.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not aware of the Blake example. I’m usually not disturbed by the “alternate justice” aspect of GAD. The only two I found somewhat offensive were Carr’s Seat of the Scornful and the neo-GAD Eleventh Little Indian.

LikeLike

It’s something that generally doesn’t disturb me at all. The Blake example just shocked me since it was a case of a member of the intellectual elite suggesting that members of the intellectual elite should be allowed to get away with minor legal transgressions such as murder.

LikeLike

I should I guess make it clear that even thought I thought Blake/Day-Lewis was making an outrageous suggestion that is one of the things I love about GAD (and the genre fiction of that era in general). Authors felt quite comfortable about throwing in the occasional outrageous suggestion and being provocative.

They were relaxed enough to raise awkward questions about the criminal justice system. You had guys like Erle Stanley Gardner making it quite clear that a fair trial was something that the little guy could never hope to get because the system was stacked against ordinary people. And making it clear that if you trusted the police you were a blockhead and if you trusted the D.A.’s office you were deluded. And you had guys like Conan Doyle campaigning to have miscarriages of justice investigated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice

LikeLike

Pingback: REBRANDING #5/BOOK REPORT #WHATEVAH: Death of Jezebel | Ah Sweet Mystery!