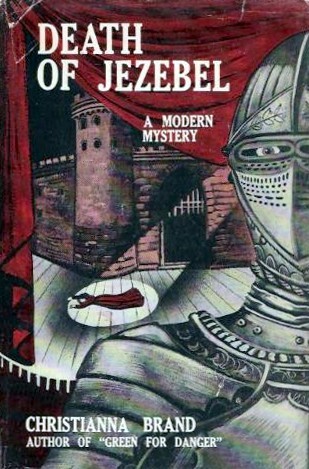

For the second lovely time, my Book Club has chosen Christianna Brand, and the timing couldn’t be better. For one thing, Death of Jezebel (1948), her fifth mystery, happens to be next on my list for the glorious wallow that is the Re-Branding Project. For another, it happens to have been, for many a year, the most elusive title in the canon. I understand why Green for Danger is easy to find – there was that movie, after all – but you don’t hear people griping over scarce any copies of the other books are, and I can’t figure out why.

As for me, well, I’ve had a nondescript library copy in my hands for years and years, but I hadn’t revisited Jezebel since my long-ago first read, and I couldn’t remember much. I thought I remembered the killer, but, as it turns out, I was happily, gloriously wrong. I turned out that I had forgotten quite a lot actually, and I was excited to return to Jezebel and see what all the fuss was about. Plus, thanks to its recent reissue by the British Library, my friends at Book Club could easily join me on this sojourn.

What makes Jezebel stand out from the rest is that it is a full-blown impossible crime mystery: Isabel Drew, whose machinations around her circle of “friends” have earned her the justifiable nickname of “Jezebel,” appears to be pushed from a tower in front of thousands of witnesses. When her dead body is examined, she has been strangled – but only a ghost could have approached her to do the deed. For years, the fanboys who read Robert Adey’s Locked Room Murdersfrom cover to cover and have wondered frantically about entry #213 have been eager to get their hands on this one – and now they can! (While Suddenly at His Residence dabbled with locked rooms and missing footprints, Jezebel is a full-blown, dazzling impossible crime mystery with possibly Brand’s strongest puzzle yet.)

As for this Brand fan, I have to say that the howdunnit aspects were extremely satisfying, for reasons I will get into in the Spoiler section, but for me the best part of Death of Jezebel is that Brand gives us two detectives for the price of one. Young, stalwart Scotland Yard Detective Inspector Charlesworth (from Death in High Heels) is back, and he is joined by Inspector Cockrill (from everything else!), who is up in London from Kent in order to attend a conference that he never quite makes. Cockie is the grumpiest fish out of water who ever lived, and when murder strikes before his very eyes, he feels seriously inconvenienced to have no power or fame in the Great City.

“’Never heard of me, I suppose,’ said Cockie, wistfully.

“’Of course, Cockie, you’re used to having the Law behind you, and everybody in Kent being terrified of you, and you being the sort of center of everything . . .’

“’And you think I can’t get anywhere on my own personality?’ said Cockie grimly.”

The pairing of Cockrill and Charlesworth is an inspired and hilarious battle royale worthy of King Kong vs. Godzilla or Freddy vs. Jason. Charlesworth, safe in his professional capacity, can be both charming and condescending:

“‘Cockrill, Cockrill . . .’ said Charlesworth, thoughtfully biting upon his underlip. ‘Where have I . . .? Oh, yes! It was you who made such a muck of that hospital case down in Kent!’ Innocent of the slightest intention to wound, he shook the Inspector thoroughly by the hand. ‘Delighted to have you down here. Hang around . . .”

Privately for Charlesworth, Cockie is a hick interloper (“All very well to potter around and build up neat theories in the intervals of some tin-pot conference . . .!”), while Cockie shows us that, when push comes to shove, nobody can be more childish or irascible when it comes to a rival colleague:

“Inspector Cockrill . . . observed to himself with sardonic satisfaction that his colleague was covering up, with a lot of rather frantic badinage, the fact that he did not know what on earth to do next. With any luck, Detective Inspector Charlesworth was going to ‘make a muck’ of the Jezebel case! Until, of course, he, Cockie, the despised, the rejected, stepped in to put things straight for him.”

It’s marvellous stuff – but, of course, you want to know about the mystery. Death of Jezebel polishes the basic structure Brand had been honing throughout the 1940’s: the well-wrought cast of characters (listed for your edification at the start), a text suffused with subtle humor and extreme emotions, and a plethora of false solutions, all leading to a satisfying conclusion. The novel is suffused with a post-war sensibility without being preachy or obvious. Jobs are scarce, and some characters are hard up; others have not recovered from the bombs bursting in air, and are emotionally unstable. While Brand’s closed circles tend to be composed of generally likeable people caught in extremis, here her characters are suffused with bitterness, suffering both personal losses and deprivations caused by both the war and their own human baseness and creating her least likeable dramatis personae yet.

In a prologue, we learn that eight years earlier, a charming young soldier named Johnny Wise had killed himself after finding his girl, Perpetua Kirk, in the arms of fading actor Earl Anderson. It was Isabel Drew who set up Johnny to walk in on the pair, and she may be the coldest fish Brand has ever created, taking no blame for what happened. (“I was half-seas over myself, and he got on my nerves, standing there insisting on seeing her. How was I to know that he was such a little Puritan?”) Since that time, Perpetua has lived a shell of a life, stepping out with Earl when he’s in town – and feeling nothing.

The three are brought together in the present day to participate in a lavish medieval pageant that seems designed to advertise and sell new houses and domestic conveniences, like Flee-Flea Insect Powder and Bowels-Work Barley Sugar. In the way that mysteries work, the others who join them in this endeavor also happened to know Johnny: elderly Edgar Port, who harbors a deep crush on Isabel while his wife remains locked away in an asylum; the charming and manly Susan Betchley, and the dashing Dutchman Brian Bryan who counted Johnny among their favorite friends. Finally, we have George Exmouth, a disturbed teenager who did not know Johnny Wyse but would like to get to know Perpetua a whole lot better.

Tensions are ramped up during preparations for the pageant, which involves a team of eleven knights in armor (including Brian, George, and Earl) surrounding a battlement on which will appear the fetching Isabel reciting a speech. Isabel, Perpetua and Earl are bombarded with threatening letters, leaving one to question whether someone in the wings is out to avenge Johnny’s suicide. On the fateful day, Isabel appears on the balcony – and plunges to the ground in front of a horrified crowd. Cockie is there to observe it all, and Charlesworth soon makes his entrance. Together they realize that Isabel must have been pushed – and yet nobody could have pushed her!

Always, there is that undercurrent of Brand-ian humor that suffuses the proceedings, like the fact that the eight other knights are all unemployed actors who answer police questions “in plushy voices made plushier by RADA.” But there is something grimmer underneath, and this plotline reminds me, funnily enough, of all those 80’s slasher movies that centered on revenge for past evils or maybe the more elegant but no less horrifying giallo films of Dario Argento. (To prove this, Brand even provides an act of pure, unmitigated gore!) The author usually illustrates the lacerating effect that mutual suspicion has over a close group, but here the sickness has been festering among them all ever since Johnny’s death. For once, the horrors of murder seem poised to deliver justice for an earlier wrong and to provide the innocent with an opportunity to finally heal.

Most mystery authors toy with the concept of the “false solution,” but here Brand makes an art of it. Fully a quarter of the novel consists of our two detectives standing on the pageant stage with the suspects and taking them through one theory after another. Each “solution” appears reasonable, even as certain details appear to cancel out one after another. Most of them are presented by Charlesworth, with Cockie standing silently to the side, deriding all his efforts but using this fact or that one to “click, click, click” the proper solution in place. (Brand gets some clever use out of that “click” sound at the climax.)

What is so satisfying about the final solution is that it perfectly justifies each bizarre aspect of the case. My problem with a lot of impossible crime mysteries is that, unless the impossibility comes by accident, there never seems to be much of a good reason for the murderer to kill this way, except for dramatic effect. Here, there are reasons – and good ones – for everything that happens, and they supersede all the viable-but-wrong solutions that had been earlier presented.

If, in the end, Death of Jezebel lacks for me the emotional punch of my favorites (Green for Danger and Tour de Force), the brilliance of its puzzle and the joyful humor of the Cockrill/Charlesworth smackdown makes this a classic not to be missed. How thankful we are to the British Library for making it readily available again.

* * S P O I L E R S * *

It has often been stated in this blog that we mystery fans much prefer having the wool pulled over our eyes than being all clever and such as armchair detectives. I approached this re-read with the knowledge that Perpetua Kirk was the killer and managed to enjoy Charlesworth’s theories accusing all the others, plus the fact that everyone except Perpetua has a moment to confess to the murders and have their actions explained – wrongly, as it turns out.

Thus, when Cockrill takes over and grabs Perpetua by the wrist – the woman he has known and loved since her girlhood in Kent – and offers the best theory yet, one that gives us the motive that was staring everyone in the face and a nice explanation – I was ready to close the book with a sigh and do my write-up.

That’s why the discovery that Perpetua was not the killer (indeed she could not have killed Earl Anderson) and that Brian Bryan was a much darker and more complex character than we thought was such a wonderful surprise to me. Evidently, I had remembered the wrong solution in a mystery that contained six or seven!!!

The idea that the extra suit of armor had been used as a blind atop one of the horses had figured into several of the theories, but of course it made sense that Brian, with his equine expertise, would know best how to handle the armor and the horse. It provides a sound reason for Isabel’s body having to fall from the balcony – not merely for effect but to spook the horse. The biggest objection to his having done so was George swearing that he had looked into Brian’s piercing blue eyes as the murder occurred. Having this be the reason for Earl’s beheading is both blood-curdling and logical.

THE MYSTERIES OF CHRISTIANNA BRAND

Death in High Heels (1941)

Heads You Lose (1941)

Green for Danger (1944)

Suddenly at His Residence a.k.a. The Crooked Wreath (1946)

Death of Jezebel (1948)

Cat and Mouse (1950)

London Particular a.k.a. Fog of Doubt (1952)

Tour de Force (1955)

A Ring of Roses (published under the pseudonym Mary Ann Ashe – 1977)

The Rose in Darkness (1979)

Read recently and loved it so I followed up by watching and then reading Green for Danger. Why it’s taken me so long to get into Brand, I truly don’t know. At least in those two books, she’s really quite brilliant.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’m glad you enjoyed both, Jo. My favorite might be Tour de Force, although both of the ones you’ve read might be stronger mysteries.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brad, I’m glad you enjoyed it more this time, and recognized— as few do— that the key clues are not such matters as the two nooses or a “t” in a name (though those are admittedly fun), but the justified motivation behind the decapitation and throwing Isabel over the balcony.

Though it’s my favorite novel in the genre, I do recognize that it is not without faults. Here are a few I’ve noticed:

SPOILERS!!!!!!!

1. Not once but twice is a guilty knowledge clue (“Red shoes? I never mentioned they were RED shoes? How did you know they were RED shoes?”)— one of them concerning Edgar Port (regarding his knowledge of the poem) and the other George Exmouth (regarding his knowledge that Earl was already dead)— raised and then summarily dropped prior to any suitable investigation or explanation. I admire that these clues did not turn out to be the conclusive indicators of the solution (thus taking this novel out of Murder She Wrote territory), but that Cockrill and especially the less imaginative Charlesworth would let the matters drop without even a bit of further examination I find extremely unlikely.

2. Why make the death an impossible crime at all? Is that part of that “cloak of fantasy” that fits in with the culprit’s madness? That certainly fits in better than if it had been a purely pragmatic killing, but it still strikes me as not entirely motivated (especially as all impossible crimes leave unclosed cases, leaving clouds of suspicion upon the innocent).

3. Susan Betchley says that she must’ve been whistling “Sue Le Pont D’Avignon” because it’s the only tune she knows. Now, I can well imagine only knowing one tune on the piano or the uke. But only knowing one tune for the purpose of whistling? Really!? It’s a tiny thing, but still…

4. I just have trouble believing that if the killer really cares “not a jot” about hanging, he’s still willing to kill an Inspector he’s always liked for the sake of getting away.

5. There’s actually a medical fact that evidently makes the whole plot impossible! That’s too bad, but it really doesn’t bother me all that much. The ingenuity here is too great.

6. The novel’s biggest flaw in my opinion is a lack of clarity as to the layout of the setting. The diagram certainly helps, but we could really do with one that shows where the stables, dressing rooms, etc… are located.

Again, all that said, it’s still my favorite detective novel. I’ll grant that it doesn’t pack the emotional punch of other Brand novels (and interestingly— and perhaps intentionally— leaves every single character [including Charlesworth and even Cockrill] with a degree of personal dissatisfaction). But the characters are nicely drawn, nonetheless. I would also have liked a longer post-denouement wrap-up… but for me that’s a very minor issue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

SPOILERS AHEAD:

I wrote SO MUCH . . . and then decided to cut it down. Murderers tend to possess a strong desire for self-preservation, but as Brian referred to himself as an “executioner” and made a big deal about stopping his persecution of Perpetua once he realized she had been an innocent victim, too, it’s hard to fathom his willingness to let the others suffer from police suspicion. I chalk up the method of killing Isabel as a public execution and ignominious end for this horrid woman he believes to have been a murderer. The impossible-ness of it helped establish an alibi; plus, it allowed Brian’s vengeance toward Earl to serve another purpose in his plot against the principal actor in Johnny’s death. In fairness to Brand, an earlier doubt is cast on Brian’s sanity, albeit in a way that charms rather than inspires fear or suspicion. I like that even his “foreign” habit of carrying a Mac and hat in hot weather actually has a murderous purpose – although, now that I think of it, I seem to recall that the more innocent explanation was expressed as one of his thoughts. I must be wrong there.

I didn’t emotionally take to this group as I do to others in Brand, and the suddenness of the ending, plus the emotional dissatisfaction that, as you point out, all are left with in the end, didn’t help. It shows that there is a purpose to all those post-reveal “But how did you know it was Thelma, Miss Marple?” scenes, and a little falling action after the climax doesn’t hurt. Still, I’m not sure how ANY of these innocent suspects could find some sort of happiness, at least for a while . . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree that the characters are not as emotionally compelling as in some other Brand novels, but still more so than in many (even most) books of the genre. And, I find the universal concluding dissatisfaction of the characters (note that not even Charlesworth Cockrill achieve their purpose in being there) more interesting than personally dissatisfying for me. For, it is so thorough and universal that it strikes me as an intentional point (though I don’t know what that point is).

The lack of “How did you know it was Thelma?” doesn’t bother me, as all of that was thoroughly explained (even more so than usual) in the dénouement. But I would have liked to have seen a bit of how the characters are going to face the future.

I certainly see the earlier indications of madness in Brian— I just don’t see very much of the function of making the crime an impossible one. A public one, sure— and even one in which the innocent are seen to have alibis. But an impossible crime doesn’t clear anyone, it just extends investigation until a possible solution— very likely incriminating an innocent person— is found. And an unwillingness to let the innocent be harmed should surely extend to the life of a likable policeman. It’s hard to reconcile the final “click, click, click” with the “I’ve always liked you, inspector” and “I don’t care a jot.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Incidentally, if it had ended up with the penultimate solution— the one you remembered— I would’ve been EXTREMELY disappointed. That might have still made an interesting novel, but not a very deceptive puzzle plot (indeed, Brand is employing omission of overt suspicion to lead the reader to that false solution).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, I very much agree! And it confused me that Brand never really included Perpetua in the detectives’ consideration. This, I feel, is often a flaw of Christie’s, who often plants a dynamic character on the scene and never casts suspicion on them until the final reveal. Turns out Brand IS better than that!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, yes, it’s a wonderful employment of the “Deception Expectation Principle.” The inverse of “Exoneration by mere acknowledgment of possibility’ it’s “incrimination by conspicuous absence of possibility acknowledgment.”

LikeLike

But no wonder your memory of thr book was not all that enthusiastic, if you thought Perpetua was the culprit! For me, that would be almost like remembering the mafioso solution to Orient Express!

LikeLike

Well, maybe more like remembering Angela as the culprit of Fuve Little Pigs. Better analogy.

LikeLike

Sounds great. Not read it yet but it’s climbing up the TBR pile.

LikeLike

Glad you liked this one as much as it deserves! I can’t deny the faults Scott calls attention to above, but I think it’s a testament to the novel that I can acknowledge the faults and still find the effect of the novel so salient. This is, as of writing this comment, my favorite mystery novel ever written, though given my recent reading into Japanese language mysteries I feel its place might be somewhat threatened…’

After her somewhat inauspicious beginning with DEATH IN HIGH HEELS and HEADS YOU LOSE, two fine but uninspiring novels, Christianna Brand basically produced back-to-back-to-back-to-back masterpieces. GREEN FOR DANGER is obviously the finest example of Brand’s ability to use misdirection to not only trick you into ideas, but to hoodwink you into believing ENTIRE false narratives… SUDDENLY AT HIS RESIDENCE is one of my less favorites but everyone else considers it a great so I’ll relent and count it… and then DEATH OF JEZEBEL, the finest mystery novel I’ve ever read, followed up by CAT AND MOUSE which I haven’t read but can only assume is great… and then capping it all off with the rarely discussed and less tricky but nonetheless brilliantly conceived FOG OF DOUBT and the audacious alibi plot of TOUR DE FORCE.

So, what is that? 5 verifiably great novels, making half her mystery output certifiable masterstokes? Nobody else has that kind of track record (no, not even Christie, Queen, or Carr), with that level of consistency. I’m sure Brand could’ve spat out five more masterpieces of mystery plotting but she humbly bowed out of the genre before she could brashly overshadow everyone else!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Could she have, though? There is a risk to being prolific, and if we look at percentages rather than numbers (50% are NOT masterpieces?!?), then Brand fares about the same as Christie, Queen or Carr.) What she definitely saves us from (that the others did not) is an inauspicious decline. Even her final mystery, THE ROSE IN DARKNESS, written thirty years after this, is charming and haunting.

For me, RESIDENCE has charming characters but not half the mystery of JEZEBEL. I remember nothing of CAT AND MOUSE, so I’m very much looking forward to that one!

I forget: did you read SHADOWED SUNLIGHT, Libby? It is mentioned in JEZEBEL and even referred to as one of Charlesworth‘s failures!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t read that one yet! It was in a BODIES FROM THE LIBRARY, yeah?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’ in the 4th edition . . . and it’s GOOD!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You can stretch that five to seven by adding A Ring of Roses and The Rose in Darkness – both really solid books. Of the five you listed, Cat and Mouse might be the lesser simply because the mystery isn’t at the forefront of the story – in fact you’ll read most of it not quite understanding whether there is a mystery – but it features a lengthy head spinning conclusion that makes it a classic in my mind.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ve never read A RING OF ROSES; fortunately, a friend sent me a pdf of it. I love THE ROSE IN DARKNESS: Brand pulled no punches when it came to her solutions.

LikeLiked by 2 people

One of the greatest GAD novels ever written, and a master class in misdirection.

By the way, for a book with such a small cast, it’s interesting that there are two significant characters who never come under suspicion (and I don’t mean Cockrill and Charlesworth). When I first read the novel, I thought both of them were strong contenders for the killer. I should probably put this under a spoiler warning, in case anyone wants to know what *doesn’t* happen:

SPOILER

SPOILER

SPOILER

– I was surprised that Charity Exmouth was never suggested as a candidate for Johnny’s mother. In her role as the designer of the pageant, she could have included some prop or architectural feature which allowed her son George (who would therefore be Johnny’s brother) to commit the murder.

– And the second unsuspected suspect is…Johnny Wise! When you combine the vague description of his suicide (notice that the scene abruptly cuts away *before* his car crashes) with the fact that he has a twin brother, alarm bells should be going off in the head of any experienced mystery reader.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I suspect that both were calculated by brand as useful “outlets” for possible reader suspicion.

As a magician, I always include additional avenues of possibility for the purpose of misdirection— possibilities which are ultimately demonstrated as untenable— for if there truly seems to be no possibility, the one true possibility becomes more vulnerable to disclosure (it’s a common technique among magicians for which I cannot take credit). The same type of technique is used by the mystery writer, but a mystery writer doesn’t necessarily need to plug up those holes as thoroughly, for convincing the reader of the “inevitable” truth of the true solution is far more important than the pricing the total impossibility of all other considerations.

I hadn’t even considered the second of your suggestions— the elipse struck me as so dramatic as to seem only to avoid mentioning the details of an unavoidable consequence. I suppose you’re right, but it would’ve taken a lot to convince me in the denouement of the circumstances by which that character realistically continued as a viable possibility— especially as premeditation on his part in the opening chapter seems out of the question. This seems very different to me than a “missing in action” kind of situation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with you about Johnny, Scott. My opinion about Charity is slightly different. (See my own reply to Nick.) I always like Brand’s “extra” characters – the husbands and boyfriends in Death in High Heels, the commander and patients in Green for Danger, and so on. Since they’re not on Brand’s list, however, I can never put them under suspicion. Not only does she usually do a good job of showing how only a certain group could have dunnit, she states plainly that her list contains “two victims and a killer.” It’s interesting that she does include Johnny Wise on this list, but she states clearly that his death and the avenging of it are what this book is about. It narrows the possibilities considerably.

When Van Dine, Queen and Ngaio Marsh included their lists, they named every character in the book. This was especially helpful to Queen, as certain books contained killers who you would not expect to be on a suspect list. Christie, on the other hand, never made lists at the start of her books, and I am increasingly amazed at the editorial chutzpah of the Pocketbooks editions and the Dell Mapbacks, both of which had somebody write descriptions – and not of EVERY character but only certain ones. (Not all of these were suspects, either, so what gives?)

Death on the Nile, to my knowledge, was never published in an edition that included a cast of characters, and a lot of those passengers are not suspects at all. Although they could be lumped under suspicion of being a jewel thief, Christie really doesn’t go there with Miss Bowers, Cornelia Robson, Jim Fanthorp, or Dr. Bessner. The play version I just directed underscores Christie’s lack of concern that everyone be suspected: Dr. Bessner states a motive and then is dropped from suspicion, while the Cornelia Robson figure (here named Christina Grant) is a witness and a secondary love story. Mr. Fergusson, the Communist, (here named Smith) makes no threat against Linnet (I added it in, and the actor did a great job of inspiring suspicion). We had to work to make it less obvious who the killers were. Meanwhile, Anthony Shaffer goes and gives EVERYONE a motive – that’s the movies for you!

LikeLike

I think of Charity Exmouth as a wasted opportunity. The circle could have included an extra suspect, an older woman, and she could have easily been even an acquaintance (a mother FIGURE) to Johnny and thus possess a strong motive. Her position at the pageant could have cast a lot of suspicion on her as well. As for the whole twin thing – I did wonder why the possibility hadn’t even been mentioned, but I think, like Scott does, that this was a matter of a clear death rather than jumping off a cliff or “perishing” in a fire (cue the missing tramp). Johnny died in a car crash, pure and simple. I did figure out that Susan was Johnny’s twin SISTER – except, of course, she wasn’t! – and I liked how the spirit of the twin haunted the story almost as much as Johnny’s death did (and led to a similar tragic end).

I do think the suspect list was a bit sparse here, though. I never bought George Exmouth as a possible killer. He reminded me too much of Edward Treviss in Suddenly at His Residence, who was given far too much page time wandering through his self-delusion and convincing himself that he had killed Grandfather. At least we got just enough of George and no more.

LikeLike

But as far as I’m concerned, that’s the point. Even if one doesn’t consider George a viable suspect, the remaining pool (Edgar, Susan, Perpetua, Brian) proves large enough, as it succeeds in deceiving. The great puzzle plotters can achieve this with a very small pool of suspects (I think of Five Little Pigs and Cards on the Table). In a sense, I think Carr even pulled it off with 2 suspects— though I’ve often expressed my dissatisfaction with the solution of The Crooked Hinge, I think he succeeds in keeping the reader uncertain as to the identity of the true claimant (and shifting the reader’s trust between the two) for a large section of the book. In such situations, it is certainly not a matter of the reader never considering the culprit’s guilt, but that it nonetheless comes as a surprise when ultimately revealed.

As for Charity, I don’t see her as a missed opportunity, but one that is effectively used. Brand never places overt suspicion on her, but the very fact that we entertain the thought is proof of its obfuscating effectiveness. Just as with not mentioning the possibility of Perpetua’s guilt, the absence of overt consideration invites the reader’s suspicion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think Perpetua works well on fans like us who look for this stuff. Here’s someone who’s right in the thick of it, and the fact that 1) she’s an old friend of Cockie (like other Brand killers before her), 2) she was the victim of chicanery, both in terms of being threatened AND in being subdued during the murder, and 3) not even Charlesworth entertains suspicion or offers a theory. Cockrill’s Perpetua “solution” is a good one, if not a satisfying one, and I was led by the nose to it.

Charity, on the other hand, never comes under suspicion. I agree that we don’t need her to, but she seemed poised to become an interesting character and then was essentially dropped.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I see what you mean about not being on the list of suspects. But in general— without consideration of a suspects list— I don’t think an author ever need mention the possibility of a character’s guilt to be considered by the reader. Indeed, the fact of the possibility not being mentioned is the catalyst for suspicion. That’s the essence of the deception expectation principle.

I have also found Brand’s “two victims and a killer” pronouncements very tantalizing, as she never clarifies if these catagories are mutually exclusive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Notas sobre La muerte de Jezabel, 1948 (Inspector Cockrill # 4), de Christianna Brand (traducción de Elena Magro Gómez y Manuel Navarro Villanueva) (una relectura) – A Crime is Afoot

Pingback: THE 2022 ROY AWARDS: Making My Case for Jezebel | Ah Sweet Mystery!