And now we come to the final four tales in this, my favorite Agatha Christie story collection. After the three male members of the dinner party at Colonel Bantry’s estate tell their stories, Sir Henry Clithering issues a complaint:

“We are a company of six, three representatives of each sex, and I protest on behalf of the down-trodden males. We have had three stories told tonight – and told by the three men! I protest that the ladies have not done their fare share.”

“’Oh!’ said Mrs. Bantry with indignation. ‘I’m sure we have. We’ve listened with the most intelligent appreciation. We’ve displayed the true womanly attitude – not wishing to thrust ourselves into the limelight.”

However, it most definitely is the women’s turn in the limelight, and their stories are made even more delightful by their distinctive narrative voices. Plus, the stories are as varied as their storytellers: a nearly inverted murder case, a grand whodunit on a country estate, and a most unusual case of theft and mistaken identity.

CASE #10: “A Christmas Tragedy” NARRATOR: Miss Marple

Miss Marple relates her vacation to the Keston Spa Hydro, where she encountered a married couple and states, “I felt no doubt in my mind the first moment I saw the Sanders together that he meant to do away with her.” From there, Miss Marple describes her futile attempts to save Mrs. Sanders from being murdered and her further exploits at bringing a vicious killer to justice. The grand bonus of this story is the amount of information it reveals about the way Miss Marple thinks. She talks about the frustration of a woman of a certain age trying to get people to believe the worst of others:

“And if one tries to warn them, ever so gently, they tell one that one has a Victorian mind – and that, they say, is like a sink.”

Sir Henry asks, “What is wrong with a sink?”

“Exactly,” says Miss Marple. “It’s the most necessary thing in any house; but, of course, not romantic.”

She talks about how important domestic matters have been to her understanding of human nature, despite men’s lack of interest in such things. For this reason, sometimes Miss Marple can just look at a person and know that they are wicked. Perhaps this is why so many of the solutions in Marple tales rest less on logic and more on instinct. This frustrates many of my fellow Christie fans, who prefer the prevailing logic of a Poirot novel, yet here at her very origin, Miss Marple is making a persuasive case for a different brand of sleuthing. We do not doubt for an instant that Miss Marple is correct about Mr. Sanders! Therefore, we share her sense of shock when she learns that Sanders must be innocent of his wife’s murder!! We will find a similar situation in the first Miss Marple novel, The Murder at the Vicarage, but, since she plays her hand closer to the vest in that case, it’s great fun to see her being so open with her fellow dinner guests, leading them point by point through her reasoning, and then surprising them just the same in the end.

Finally, we get a good look at Miss Marple’s – and Agatha Christie’s – notions of crime and punishment:

“ ‘(X) was hanged,’ said Miss Marple crisply. “And a good job too. I have never regretted my part in bringing that man to justice. I’ve no patience with modern humanitarian scruples about capital punishments.”

The old lady will utter these sentiments with equal fervor in as late a book as 4:50 From Paddington, when she descries the elimination of the death penalty as punishment for a very wicked murderer and as a deterrent to evil.

CASE #11: “The Herb of Death” Narrator: Dolly Bantry

“I never can tell a story properly; ask Arthur if you don’t believe me.”

“You’re quite good at the facts, Dolly,” said Colonel Bantry, “but poor at the embroidery.”

And, with that pronouncement, major fun is had by all as Dolly Bantry – humorously nicknamed “Scheherazade” by Sir Henry, trips and falls over her turn, and joy comes to the reader from watching the Tuesday Night Clubbers attempt to pull the story out of Mrs. Bantry’s muddled head. She admits at the start that the subtleties of storytelling elude her:

“I’ve been listening to you all and I don’t know how you do it. ‘He said, she said, you wondered, they thought, everyone implied – ‘ well, I just couldn’t, and here it is! And besides, I don’t know anything to tell a story about.”

But she does have a fine mystery to relate, a complex tale of mass poisoning and murder at Clodderham Court, the home of Sir Ambrose Bercy. At a dinner party where stuffed duckling is served, someone mixes foxglove leaves with the sage, everyone gets sick, and Sir Ambrose’s lovely young ward dies. It’s a wonderful, traditional whodunit, full of interesting characters and romantic intrigues, and Mrs. Bantry’s strength is in her extremely partisan views of the dramatis personae in her story, views she takes very much to heart.

Miss Marple’s strength lies in her ability to measure the degrees of accuracy in each of Dolly’s opinions and to strip the emotional reaction down to its core of truth. The rest of the group propose strong – and thoroughly incorrect – solutions to the crime, and I have to ask myself, not for the first time, why Dr. Lloyd didn’t notice an important medical fact which provided the basis for Miss Marple’s reasoning.

CASE #12: “The Affair at the Bungalow” Narrator: Jane Helier

If Dolly Bantry was an unreliable narrator in the previous story, Jane Helier is a nightmare. So you will forgive me if I myself am a little muddled by the facts in this story, but that sort of becomes the point. This is without a doubt the funniest tale in the collection, and for reasons which I will not elucidate, it reminds me in a funny way of Anthony Berkeley’s masterpiece, The Poisoned Chocolates Case.

It begins comically as Jane offers to recount a mysterious event that happened to a friend of hers.

“Everyone made encouraging but slightly hypocritical noises. (They) were one and all convinced that Jane’s ‘friend’ was Jane herself. She would have been quite incapable of remembering or taking an interest in anything affecting anyone else.”

And when Jane describes her “friend” as “an actress – a very well-known actress,” Sir Henry Clithering thinks to himself, “Now I wonder how many sentences it will be before she forgets to keep up the fiction, and says ‘I’ instead of ‘She’?”

Not long at all, but that is just the beginning of the group’s trouble at getting Jane to give a coherent and suitably detailed account of what went on at The Bungalow, Riverbury, when a young playwright was lured to what purported to be a meeting with Miss Helier but which takes on more sinister overtones as the story progresses. I want to let you discover the humor for yourself, but I do get the giggles when I recall the sequence of the group trying to assign a fictional name to each person and place. I’ll leave it at that.

I’ll leave the plot at that as well. Lots of things seem to happen at that bungalow, not all of them clear to me. But the final twist of this story is among the most delightful in the collection, and it is the reason I associate this story with the Berkeley novel.

THE THIRTEENTH CASE: “Death by Drowning” Narrator: Agatha Christie

The final tale in the collection is not a murder in retrospect but an actual case. It is important because it shows us the Miss Marple who will turn up a year later in The Murder at the Vicarage, the old lady who takes it upon herself to lead the authorities to the truth about a case that they would otherwise never see.

This story takes place during a subsequent visit by Sir Henry Clithering to the Bantry’s for the weekend. His hosts are upset by the news that a local innkeeper’s daughter, Rose Emmott, has drowned herself. She had been known to run about with the boys, and now she had “got herself in trouble,” as Colonel Bantry puts it, adding with the loquacious stupidity of his sex, “Dolly was all up in arms for the girl – you know what women are – men are brutes . . . But it’s not so simple as all that – not in these days. Girls know what they’re about. Fellow who seduces a girl’s not necessarily a villain. Fifty-fifty as often as not.” Really, for 1930, it’s amazing how modern this story’s sensibilities are!

Almost immediately, Sir Henry is summoned by Miss Marple, who is equally distressed by Rose’s death. Not only has the girl actually been murdered, but Miss Marple claims to know the identity of the killer, not because of any proof but because of her understanding of human nature. Clithering is understandably dubious of her claim, at which point Miss Marple calls upon their previous experiences together:

“’You may remember, Sir Henry, that on one of two occasions we played what was really a pleasant kind of game. Propounding mysteries and giving solutions. You were kind enough to say that I – that I did not do too badly.’

“’You beat us all,’ said Sir Henry warmly. ‘You displayed an absolute genius for getting to the truth.’”

On the strength of this, the retired Commissioner undertakes to investigate the circumstances of Rose’s death, and Miss Marple is good enough to supply the name of the person she suspects on a slip of paper. Sir Henry carries this paper with him throughout the rest of the case, adding suspense to the proceedings as we watch him interrogate each suspect and witness, not knowing whether or not that person is the one who has been named by Miss Marple. For, by this point, the reader has no doubt that whoever the old lady named will turn out to be the killer.

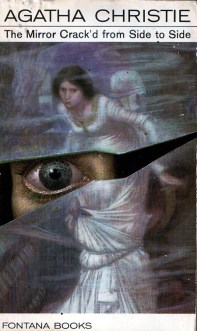

This story reminds me a great deal of Christie’s 1939 novel Murder Is Easy, where a man is accosted by an old woman who knows the identity of a fiendish serial killer residing in her small village. That old lady dies before she can name names, although she does leave a juicy clue as to the murderer’s identity. Miss Marple is a more straightforward old lady. She sees beyond the lies and flourishes to the bare truth in a case. The subsequent twelve novels (and seven more stories) that Christie wrote about her may not satisfy those who crave the tightest and most logically clued of puzzles, but they constitute some of the most poignant mysteries in the Christie canon. I do agree that Hercule Poirot is featured in the lion’s share of Christie’s cleverest cases – just think of Roger Ackroyd, Death on the Nile, and Murder on the Orient Express, to name a few – but A Murder Is Announced is just as clever, and for sheer emotional impact, the endings to Miss Marple novels like A Pocketful of Rye, The Mirror Crack’d From Side to Side, and Nemesis can’t be beat.

Thank you for following this journey through The Thirteen Problems. Here’s to a happy, healthy, safe Thanksgiving for us all!

Modern? MODERN? Victim blaming is older than the pyramids, and too prevalent now!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are absolutely right! What I think I meant to say was, how come we haven’t become more enlightened eighty-five years later?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was taking “modern” in its commonly used eulogistic sense – my mistake! “Modern” is not always good. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Finally, we get a good look at Miss Marple’s – and Agatha Christie’s – notions of crime and punishment.”

Now, I’m not picking on you particularly here, Brad, but there’s a part of me that never quite understands when a charatcer’s opinions on something are taken to be a verbatim expression of the author’s views on the same subject. Everything else is made up – no-one assumes, say, that Agatha Christie went around solving crimes just because her characters did – so why can’t the opinions be? And why is it only the protagonist’s opinions that are taken as a facsimile of the author’s? Why not assume that the author actually share’s the killer’s opinions, or the house-keeper’s? It’s like Gideon Fell saying (in The Hollow Man) that The Mystery of the Yellow Room is the finest locked room myster ever written, and then forevermore that opinion being attributed to Carr…gah! Knowing my luck Carr will be on record somewhere saying it, but hopefully you get my point.

Ahem. Great work once again; I had honestly forgotten how funny ‘The Affair at the Bungalow’ is, but dug out my copy before embarking on this essay and it’s come flooding back to me. This is a really great way to go through a short story collection, and splitting it over a few posts stops the brain getting fatigued…if you fancy doing it again, I encourage you wholeheartedly!

LikeLike

JJ, I certainly agree in principle with what you say: every author is capable of – and many do present – so many multiple points of view that one should be most careful in attributing any certain opinion of a character’s to the author herself. Still, I think it’s widely recognized that Christie’s conservative ideology included support for the death penalty. In addition to the two works I referenced at both ends of the Miss Marple canon, there is the matter of Murder on the Orient Express, the only novel that comes to mind where Poirot let the killer get away scot free because of the strongly held belief that the victim deserved the death penalty.

And finally, I offer you this quote from the author herself which I picked up online on a “pro-death penalty opinions by authors” site: “Too much mercy often results in further crimes which are fatal to victims who need not have been victims if justice had been put first and mercy second.”

So, I think my hypothesis was correct, but, on the whole, I do agree with your opinion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hahaa, superb; now all we need is someone pointing out that Carr left a message in his will saying “Oh, and The Mystery of the Yellow Room is bloody awesome; seriously, nothing I wrote came anywhere close to that” and my ignorance will be complete 😛

LikeLike

I really enjoyed reading through this sequence of posts, Brad, and now will have to go and read the book again….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can someone please explain to me the final dialogue of A Christmas Tragedy between Jane Hellier and Miss Marple? That would be great! Thanks!

LikeLike

I take it to mean this: Jane was a glamorous movie star and is mostly depicted in the tales as woolly headed, but occasionally we see glimpses of hidden depths. Here she is touched by Miss Marple’s story of a wife murderer, and her comment that Mrs. Sanders was “all right” because she never knew her husband didn’t love her suggests that Jane herself has been greatly wronged by men before. Despite her beauty and fame,- or maybe because of it, men don’t treat her well.

LikeLike

Pingback: My Book Notes: The Thirteen Problems: Miss Marple (collected 1932) by Agatha Christie – A Crime is Afoot

I’m glad I’m not the only person who found Jane Hellier’s story confusing. I’ve read it twice, and I’m still not absolutely sure I understand everything that’s going on in it. As a narrator she’s really very funny though. This is in my opinion Agatha Christie’s best collection of short stories (and Joan Hickson does a wonderful job reading them in the audiobook version).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wrote this years ago, and I’m glad you stumbled upon it, Michael. Every few years, I listen to Joan Hickson read these stories. I love all her Marple audiobooks! Just listened to A Murder Is Announced in preparation for this month’s ranking.

LikeLike

Yes, I’m often late to the party (sometimes by years!) when leaving comments on your blog, but I’m in the middle of an Agatha Christie re-read and whenever I finish a book, I check to see what your thoughts were on it. I’m enjoying your current Miss Marple ranking project!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX (The Blog-iography!) | Ah Sweet Mystery!