One of my friend Kate Jackson’s most recent reviews at Cross Examining Crime was Death in a Million Living Rooms by Patricia McGerr. It reminded me that I have a couple of books by McGerr that have been languishing on my shelf, including Murder Is Absurd (1967), which seems to be the one book by this author that Kate has embraced wholeheartedly. It’s also a theatrical mystery. Now, my friends know that I love a good theatre mystery, which may be why these sorts of books seem to be part and parcel of my Secret Santa stash each year. I received Murder Is Absurd several years ago, and for all I know the initials of my Secret Santa that year could have been K.A.T.E.J.A.C.K.S.O.N!

Between 1946 and 1975, McGerr published thirteen novels of crime or espionage, plus a few other things. Perhaps her most lauded novel is her first, Pick Your Victim, where the killer is revealed right away and then the author presents a puzzle mystery where your job is to deduce the identity of the victim. The following year, McGerr wrote The Seven Deadly Sisters, where a young woman learns that her aunt has poisoned her uncle. The problem is that the girl has sevenaunts, and the novel passes suspicion from one woman to another until it reveals which one of them killed her husband. Kate didn’t get on much with either of these books, and since the only other McGerr I possess is Deadly Sisters, I decided to start with what Kate might consider a surer bet.

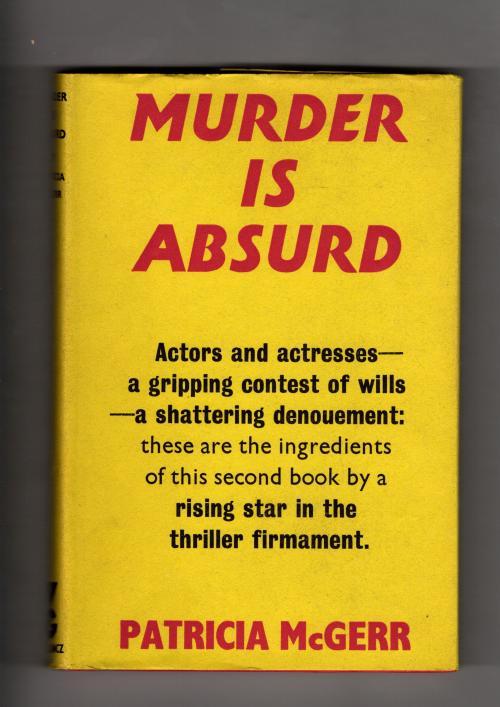

I want to draw your attention to the only covers of these books that seem to be available. First, there is the Gollancz edition, unmistakable in its vibrant yellow. The front cover bears this description:

“Actors and actresses – a gripping contest of wills – a shattering denouement: these are the ingredients of this second book by a rising star in the thriller firmament.”

This sure makes the book sound like one of those books by the likes of Ngaio Marsh where drama unfolds on- and offstage and then the star is found dead in her dressing room . . . or the blank gun seems to shoot real bullets (Derek Smith’s Come to Paddington Fair) or a person is stabbed onstage with nobody nearby (Helen McCloy’s Cue for Murder). That’s not quite what happens here – and I’d like to point out that this is McGerr’s ninth mystery, not her second.

The other cover – the one I happen to own – is more of a blast. There’s a picture of actor Laurence Olivier playing Hamlet in the 1948 film while beneath him a man seems to have spilled out dead from his wheelchair. On the top is a descriptor: The script called for suicide – but the curtain went up on murder!

This page, which certainly seeks to present the novel as a murder mystery, skirts the margins of accuracy, as does the back cover blurb. But anyone going into this expecting a victim, suspects and clues is going to be sorely disappointed. I find it difficult to assign this book to any sub-category of the genre. In terms of criminal activity, I suppose it falls under “domestic suspense,” but ultimately it’s a drama about a theatrical couple and how the unspooling of events results in one person’s redemption and their spouse’s downfall. I didn’t make much of it as a mystery, to be honest – and yet I read this one faster than any book I’ve picked up in a while.

Savannah Drake and Mark Kendall are one of the premier couples of the American stage. Years ago, Savannah was married to playwright Rex Pierson, to whom Mark was like a brother, and they had a son together named Kenny. Rex would write wonderful plays for his wife and best friend to perform together and life was good – until an automobile accident left Rex paralyzed and bitter. He became resolved to quit the theatre and to have his wife retire with him. Then one day his wheelchair plunged off the cliffs outside their beachfront home, and Rex died. The only possible options were suicide or an accident, and the papers graciously played up the latter.

Soon after, Savannah and Mark were married, and Kenny was shipped off to boarding schools in the winter and camps in the summer. Now the boy has become a man, and he has written a play in the absurdist mode. The title is The Suburbs of Elsinore, and a panicked Mark Kendall wonders if this reference to Hamlet might indicate that the plot concerns a young man whose father was murdered by his wife and brother. The play is set to be produced in a summer stock company outside Baltimore, and Mark decides to travel down there and insinuate himself into the company.

Here’s where you might expect to meet an eccentric group of actors and technicians who call each other “darling” and seem to be at each other’s throats. For that, you have to turn to Marsh, Smith or McCloy because that is not what’s going on here. For a good section of the novel, we follow the company as they begin to rehearse Kenny’s play. I have to tell you that I’m not a fan of absurdist theatre, and I can only imagine how difficult it would be for a mystery writer to create an absurdist play of her own. McGerr didn’t have experience in the theatre. She writes a dedication thanking certain people and one company, the Olney Theatre, for providing her with lots of information on the creation of a theatre production.

For me, this was the best part of the book. Warren, the play’s director, begins the rehearsal process exactly like I would have. The actors are committed to the play and not to providing any outside drama. The emotional center of this section is the relationship between Mark and Kenny, which begins in tatters and slowly begins to repair itself – not due to any artificial circumstances but to the two men coming together to produce the play. Mark begins to openly face the fact that his career has been based on facile drawing room comedies that any man with looks and a good voice could perform; Suburbs of Elsinore is a a chance for him to break with conventional theatre and hone his considerable talents in a different way.

The play confounds him – and the bits of plotline and few snatches of dialogue that McGerr provides us confounded me, too! – but the discussions Mark has with his son, with his director, and with the cast, begin to rouse something new and exciting within him. And that is exactly what happens when a company begins to take apart a play and then put it back together in their own interpretation of the text. I found this part fascinating, and it made me realize that as much as I do enjoy classic theatrical mysteries, there never really bear any semblance to reality.

And then Savannah arrives with her own cruel agenda, and the “gripping contest of wills” described on the Gollancz cover begins. Frankly, it’s not much of a contest, as the charm Savannah exudes as a cover for her true sociopathic nature tends to get her what she wants. And while we wait for Savannah to be found sprawled in a dressing room or shot to death by the blank gun . . . or for anyone to die under mysterious circumstances, the true path of the book is the professional and emotional transformation of Mark into a fine actor and a worthy man. Don’t look for any cops, and don’t look for any clues. I don’t think this is McGerr’s raison d’etre! This is the first “theatrical mystery” I’ve read where the emphasis is on the theatre and the mystery is almost an afterthought. Make of that what you will – I enjoyed myself. But I’m a little worried that Kate loved this and found The Seven Deadly Sisters disappointing. At least my copy of that book is a Dell Mapback . . . although I have to say it’s got the most disappointing map on the back that I’ve ever seen on one of these.

Well I am glad you enjoyed the theatre elements of this mystery, even if it was not a perfect read for you. At least it seems to have been a very readable one. My issue with many of McGerr’s other books, such as Seven Sisters is that the narrative over-uses the device of flashbacks – I don’t feel we get much mystery/cluing from them – and if you don’t become invested in the characters and their lives, then the flashbacks become too long. I think The Reluctant Murderer by Bernice Carey does a much better job at creating a mystery where the reader must guess the victim (the premise for Pick Your Victim). You might as well try the other McGerr you have as our views don’t always line up so you might really like it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve edited a two-volume set of Pat McGerr’s short fiction for Crippen & Landru, but sadly her closest living relative declined to give permission for it to be published. Maybe someday….

LikeLiked by 1 person

God, Josh, that’s so frustrating! I’m trying to fathom reasons, other than financial ones, why anyone would prevent their relative’s writing from being enjoyed by others.

LikeLike

Wouldn’t you know it? I bought a different double set of Bernice Carey’s work – the one you raved about the most! Let’s see how I get on with The Seven Deadly Sisters, and then we’ll see!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yay! You should read The Reluctant Murderer first though lol I think Aidan enjoyed it too.

LikeLike

I loved Death in a Million Living Rooms — it sounds similar to this, but with a TV show rather than a play — and then found Pick Your Victim to be rather disappointing given its excellent premise. She’s most assuredly of the Suspense school, but somehow sounds like she writes traditional whodunnits — which is perhaps fitting given the era of genre overhaul in which she was writing. Maybe that’s how an author survived back then…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m fascinated by the marketing of the covers of the two books I own. Clearly, they are trying to make McGerr look like a “traditional” mystery writer when she most obviously is not! It’s like the publishers of the time were fighting the experimentation and overhaul of the genre of which you speak.

LikeLike

Perhaps it’s easier to sell as a traditional mystery, and so misrepresent what it is, than to go to the effort of trying to explain what it is in the small space a book cover allows. By the time most people realised they’ve been lied to, it’s probably too late to return the book 🙂

LikeLike