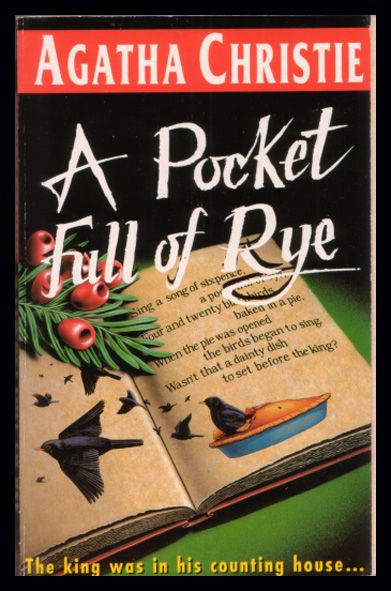

Sing a song of sixpence, a pocket full of rye.

Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie.

When the pie was opened the birds began to sing.

Wasn’t that a dainty dish to set before the king?

Juxtaposing nursery rhymes with mysteries is an effective way to mix the balm of childhood innocence with the bloody drip of murderous desires. Of course, those of us closely familiar with childhood literature know well the darkness that lies within. Poems like “Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary” and “Three Blind Mice” originated in the persecution and torture of Protestants by Mary I of England. “Ring Around the Rosie” came out of the Great Plague of 1665, when citizens thought carrying “a pocketful of posies” around would protect them from sickness (there was a 50/50 chance it could work!) And did you know that “Little Miss Muffet” was the step-daughter of a notorious doctor who crushed up spiders and fed them to her and to his patients?

S.S. Van Dine’s The Bishop Murder Case (1929) is believed to be the first mystery that based its plot on a nursery rhyme, and right off the bat we can see the problem with this. How terribly lucky for the killer that their intended victim was named J.C. Robin and went around with the nickname “Cock!?!” And that Robin’s nemesis was an engineer named Sperling, which means “sparrow” in German. And that another character was conveniently named Madeleine Moffat . . . no, really!

The story goes that around 1939 Ellery Queen came up with an idea for a mystery where folks were being knocked off with the strains of an old nursery rhyme haunting the killing spree – and then they had to pull it because another famous writer put out a book with the same basic idea. The Queen title There Was an Old Woman would be published in 1943. The connection to the rhyme is almost spurious, but it lends an appropriate atmosphere to what might be Queen’s most screwball mystery. Many authors would advantage of the macabre undercurrent of childhood rhymes: Jonathan Stagge in Death’s Old Sweet Song (1941), Queen again in Double Double (1949), Ed McBain over and over again. Most recently, Anthony Horowitz paid homage to this in Magpie Murders (2016) when he based the crimes in the novel-within-a-novel on a lesser-known rhyme “One for Sorrow.” It was a clever way to emphasize the Golden Age quality of the Atticus Pünd novel and contrast it with the more realistic shenanigans besetting the heroine of the book’s other, modern half.

And then there’s Agatha Christie, who was forever turning to literature for inspiration. The number of titles and allusions based on Shakespeare and other classic poets and playwrights could form a book in itself. And nobody – absolutely nobody – was as keen on nursery rhymes as she was. John Curran devotes considerable space in Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks to her use of them, and I think he’ll agree with me that the success ratio of this device is mixed. It works most brilliantly in And Then There Were None, providing a chilling kill list for a psychopath. It is far less successful in One, Two, Buckle My Shoe and Five Little Pigs: in the former, it provides little more than chapter titles, although Christie tries to beef up the connection with a major clue involving a shoe buckle. And in Pigs – well, frankly, it demeans Christie’s most mature work; the American title, Murder in Retrospect, is, for once, the superior one.

In A Pocket Full of Rye, Christie again makes use of a nursery rhyme for the first time in eleven years. As we shall see, she also makes use here of quite a lot of other ideas she has used before. This strategy was nothing new to Christie, and one often marvels how she could reincorporate old ideas in quite original ways. It’s just that Rye seems to be made up almost entirely of old ideas, and as we examine them, we find they aren’t used a whole lot differently from the last time. The good news is that the book is well written, funny, and ultimately moving; in a way, the regurgitation of old plotlines almost makes this feel like Christie’s homage to herself.

Oh, and there is one new thing that elevates the novel considerably, and it has to do with Miss Marple herself. In They Do It with Murders, the concept of our heroine taking on a case to help out a friend really hit its stride. This time the murder hits close to home. Her reaction to that murder, and the steps she takes to find the killer, bring her ever closer to that amalgam of sleuth and avenger that will be the hallmark of her final cases. In Rye, Miss Marple is Sherlock Holmes. She is Batman. She is Nemesis.

* * * * *

The Hook

Christie does something rather rare at the top of this novel. She opens in the offices of Consolidated Investments Trust, a London financial firm, spends three chapters establishing the milieu of the office and the people who work there – and then kicks the whole thing to the curb. For A Pocket Full of Rye isn’t a workplace mystery at all, even if Rex Fortescue meets his maker from behind his plush office desk. The staff members Miss Griffith, Miss Grosvenor, and Miss Somers are well-drawn, but they are witnesses only, providing tons of exposition and a great deal of humor. Inspector Neele, the policeman d’histoire who first appears on page 5, is one of Christie’s best – a good thing, too, because he will be holding Miss Marple’s place until Chapter Thirteen!!

For the most part, the hook here is as basic as it gets. A business executive upsets the office routine by having a fit. Christie paints an amusing picture of the efficient staff going all to pieces as they try to figure out what to do about it. Eventually, several doctors, a couple of ambulances, and the police converge on the place, but they’re all too late; the man dies on the way to hospital. There are two factors that set it apart from a seemingly ordinary murder: First, the poison used to kill Rex Fortescue is a rare one: taxine, which is derived from yew berries. Secondly, the police find something odd in searching the victim. One of his jacket pockets is full of rye.

Once it is determined that taxine is probably the cause and that it is a poison that takes time to take effect, the action moves to the victim’s country home, aptly named Yew Tree Lodge, and the novel can truly begin. All the panicking secretaries are reduced to minor characters (they’re not even mentioned in the Pocket Book character list), but they have served their purpose. The hook may not be particularly exciting, but it has served its purpose and been amusing to boot.

Score: 7/10

The Closed Circle: Who, What, When, Where, Why?

Who?

An eccentric financier suspected by the police and the Inland Revenue of making money off the black market. His inappropriately younger and beautiful wife, who is dallying with another man. His two sons who, along with their wives, are very much at odds with each other and with the stepmother. The elderly aunt who held the dead man in contempt. The daughter who seems to be the only one to show grief at the man’s death.

Does this sound familiar to you? I’ve done my best to describe the cast of characters . . . of 1949’s Crooked House. In that admittedly superior novel, old Aristide Leonides is also poisoned, and with a rare substance (eserine, found in his eyedrops). The family he leaves behind is, like the Fortescues, similarly dysfunctional and rather unsympathetic to the reader. The main difference is that the daughter in Crooked House is the main character and her romance with the hero is the prize at the end. In Rye, Elaine Fortescue may be the most sympathetic of the bunch, but she is also the least interesting. She is described as “one of those great schoolgirls who never grow up. She plays games, quite well, and runs girl guides and brownies, and all that sort of thing.”

Like Aristide, we get to know Rex Fortescue mainly in retrospect, but unlike Leonides, there is nothing benevolent about this tyrant. In some ways, he hearkens back to an earlier monstrous patriarch, Simeon Lee of Hercule Poirot’s Christmas. And again, some outward similarities between the two books’ plots add to this feeling. Both men have a dutiful son and a “black sheep” son, and they like the bad son more. Both men went out to Africa (South or East, take your pick) and swindled a partner; subsequently, a child of that partner sought revenge. Both men were lechers, whose first wives bore them children and then died in despair.

The main difference between them is that Simeon represents the Golden Age patriarchal monster at his finest, while Rex Fortescue is a newer breed: the boorish, tasteless nouveau riche millionaire. Christie revels in spending time with Simeon and his malevolent cackle, but she spares putting us in Rex’s company, for she lived among such people in the early years of her marriage. More about that later.

The Fortescue clan is made up of types we have seen many times before, but Christie’s renders them with energy and wit. These characters turn out to be exactly what they seem to be: just because we like the cad doesn’t make him any less dangerous or dishonest. Instead of characterization, we get contrasts: The wicked Rex and Adele contrast with the evangelical Miss Ransbottom, sister of the first Mrs. Fortescue. Dull Percival and his out-of-place wife Jennifer contrast with Val’s handsome, delightful, charming and thoroughly bad lot of a brother Lancelot and his delightful, charming and . . . no, she’s really delightful and charming . . . wife Pat. Adele’s “golf partner” Vivian Dubois is as disappointing a character as Gerald Wright; Inspector Neele notices that the two men even look alike, although that doesn’t matter in the scheme of things. The presence of both men is extraneous.

What elevates this cast may come as a bit of a surprise to casual readers of Christie: it’s the servants. Ellen the housemaid is the most typical, but the rest are gold. Mr. and Mrs. Crump make a helluva pair. She is one of the best servant cooks in England, but to get her, the Fortescues must hire her husband as butler, “a man with a rather spurious air of smartness, a shifty eye, and a rather unsteady hand” from his frequent tipples from the bottle.

Which leaves the two most important staff members. First, there’s Mary Dove, the housekeeper. She is young and smart and bursting with efficiency. Of course, if you’re a smart, efficient Christie reader, you will perk up at this description:

“The soft dove-colored tones of her dress, the white collar and cuffs, the neat waves of hair, the faint Mona Lisa smile. It all seemed, somehow, just a little unreal, as though this young woman of under 30 was playing a part: not, he thought, a part of a housekeeper, but the part of Mary dove. Her appearance was directed towards living up to her name.”

If you weren’t paying attention during They Do It with Mirrors, where Edgar Lawson was described using theatrical metaphors over a dozen times, pay attention to words like “unreal” and “playing a part.” To be fair, Christie uses this to lead us down a garden path; still, there will be another sort of pay-off in the end.

Finally, we have Gladys Martin, the parlormaid. She doesn’t seem promising, “an unattractive, frightened-looking girl, who managed to look sluttish in spite of being tall and smartly dressed in a claret-colored uniform.” Her first spoken words are “I didn’t do anything,” and in keeping with Christie’s servants, we are inclined to believe her. At least, we have never met a servant in the novels who was guilty of murder (except for a spurious butler who was a total fake!) But Gladys’ story is multi-layered, and she becomes an object of importance, both as the third victim (or was she the second?) and because Gladys received her training in a little cottage next door to the vicarage in the village of St. Mary Mead.

What?

The king was in his counting house, counting out his money.

The queen was in the parlor, eating bread and honey.

The maid was in the garden, hanging out the clothes,

When there came a little dickie bird and nipped off her nose.

I have pointed out similarities to Hercule Poirot’s Christmas and Crooked House, but this novel also shares an element from an even more recent novel – and a Miss Marple mystery to boot! The train that Christie wishes you to follow is that the Fortescues are falling prey to a revenge scheme by a member of the MacKenzie family, whose patriarch partnered up with Rex Fortescue on a business scheme, got cheated, and died for his troubles. We are guided by the author to assume that somebody in our cast is the son or daughter of the late MacKenzie, raised by their mom to despise the Fortescues.

Shades of Pip and Emma! To be honest, this is one of Christie’s go-to tricks that rarely hits the jackpot, partly because she tends to overdo it. In Christmas, no less than three people are masquerading as someone else. In A Murder Is Announced, Pip and Emma are living side by side right in front of everyone’s nose; the fact that Miss Blacklock has recognized Pip all along is explained at the end, just not very satisfactorily. Both novels of 1953 – this one and After the Funeral – make use of impersonation or false identity, and frankly I think these are two of the better examples in the canon. (After the Funeral is a classic!)

In the end, the MacKenzies are a red herring, but the Blackbird Mine is not. (“Uranium deposits found in Tanganyika!”) The killer wants that mine to live the good life, and so he sets about creating a crazy plot worthy of a long sought-after revenge. Fortunately, he figures out that the MacKenzie daughter is living in the house (LUCKY guess, impossible to know or deduce), the victim’s name is Rex, which means “king” (REALLY lucky . . . like “Cock” Robin lucky), and while the murder of Adele makes sense of killing off the heir, the killer is enough of a sociopath to create an over-complicated plan and add a third murder in order to conform to the nursery rhyme (and, admittedly, give himself an alibi). And how lucky that Gladys Martin is lonely enough and stupid enough that she would do all these terrible things for her “Albert” without asking a single question.

I’m not saying it doesn’t work, although it feels like a very surface, artificial plot after the more realistic Christie novels of the 40’s. I think one of the points in its favor is how long it takes for the whole thing to be revealed. For some reason, whenever I think of this novel I get the false impression that the three murders occur in quick succession. Actually, we are well over a third of the way into the novel before Adele Fortescue and Gladys Martin are killed and Miss Marple enters the picture. She mentions blackbirds to Inspector Neele around the halfway point, and we learn about the Blackbird Mine affair twenty pages after that.

That means that for a good part of the way through this novel, the reader is ahead of Inspector Neele, mostly because, unlike that gentleman, we know the title of the book in which he exists. Look! There’s a pocket full of rye on the victim, who is sitting in his counting house. Look! There’s bread and honey on the late “queen’s” tea tray. By the time we get to the clothespin on Gladys’ nose, it’s hard not to sneer at the Inspector, who has been described as someone you would think would spot the pattern:

“Behind his unimaginative appearance, Inspector Neele was a highly imaginative thinker, and one of his methods of investigation was to propound to himself fantastic theories of guilt which he applied to such persons as he was interrogating at the time.”

To his credit, Neele embraces Miss Marple’s theories pretty quickly. It helps that the mine business comes up almost immediately afterward. Before her entrance, when Neele is completely in charge, he manages to keep his interviews brisk, and the subtle grotesquerie of the cast keeps things entertaining. Once Miss Marple enters, her forays into the family are also fun and somewhat new, as in her bonding with Miss Ramsbottom; we get no sense of drag like we did in Mirrors. And it is to the book’s credit that Christie does not resort to a third act crime to goose the action, for it doesn’t need it.

When and where?

Upon his first view of Yewtree Lodge, the main setting of the novel, Inspector Neele forms a distinctly negative impression: “Call it a lodge, indeed! You tree lodge! The affectation of these rich people! The house was what he . . . would call a mansion.” Neele would know, having grown up in a cramped lodge lacking in electricity or any sort of creature comforts. This does not stop the Neeles from being “a healthy family and a happy one,” a sharp contrasts to the loathsome Fortescues basking in tacky luxury. The house is ostentatiously large with “rather too many gables, and a vast number of leaded pane windows.” The grounds have had all the nature trimmed and pruned out of them; the only natural part, “a vast yew tree . . . its branches held up by stakes, like a kind of Moses of the forest world,” is the source of death.

We who know our Christie are aware of her love of real estate and of her tendency to put her own houses in her books. As biographer Laura Thompson points out, Christie’s description of Yewtree Lodge – and, especially, of its placement as a suburb of London “almost entirely inhabited by rich City men” who loved nothing more in their spare time than a game of golf and took full advantage of the multiple courses in the vicinity – is alike to Christie’s home “Styles” in Sunningdale, the one she shared with Archie in 1926. It was ultimately an unhappy home for her, and that emotion permeates the halls of Yewtree Lodge.

Score: 8/10

The Solution and How She Gets There (10 points)

“When he was at Yewtree Lodge, he must have heard about these blackbirds. Perhaps his father mentioned them. PerhapsAdele did. He jumped to the conclusion that MacKenzie’s daughter was established in the house, and it occurred to him that she would make a very good scapegoat for murder.”

That’s Miss Marple speaking about Lancelot Fortescue, surmising what led him to craft his scheme. Once again, she has presented the police with a case that has no stand-up-in-court proof, and this time she doesn’t even suggest a trap! Her latching on to Lance is incredibly annoying, but it is tempered by her explanation of the part Gladys Martin played in the murders. Granted, most of this is based on Miss Marple’s relationship with Gladys and her understanding of servant girls in general, but in the Christie-verse this makes total sense and thus accounts for the strongest clueing in the novel: the fact that Gladys went to hang out the wash at the wrong time of day, that she wore her best stockings to do so, indicating she was meeting someone special, her vehement protestations of innocence at the start – a sure sign, according to Miss Marple (and maybe Christie herself?) that this inept parlor maid had a guilty conscience. The rest we have to assume using our common sense (Miss Marple’s sharpest weapon): who in our cast stood the greatest chance of playing a double role, that of scion to a fortune and Gladys’ unassuming beau, without the maid catching on? (Although one has to ask: did nobody in the house have any pictures of the family on display?)

The success of Lance’s plan largely depends on Gladys’ credulity, and Miss Marple makes a case of a “modern” girl like Gladys falling for the ruse of a truth drug much like 17th century girls believed in witchcraft. That she was sold this bit of goods by a hot young man didn’t hurt, but it’s still hard to explain how Lance got her to put the rye in Rex’s pocket. And Miss Marple doesn’t even try: “I don’t know what story he told her to account for the rye, but as I told you from the beginning, Inspector Neele, Gladys Martin was a very credulous girl.” That’s all we get.

There are also things stuck in that give us certain indications of where the plot may go, such as the newspaper article on truth drugs that Gladys kept, or the article about uranium that Neele reads on the train. These are by no means “fair play” clues, but sometimes in Miss Marple, an indicator is all you get.

Score: 6/10

The Marple Factor

The best aspect of They Do It with Mirrors was that Miss Marple appeared on Page One and pretty much never left the scene. Sadly, we learn that this alone does not an excellent mystery make. Christie won’t give us All Marple! All the Time! again until A Caribbean Mystery. Once she arrives at Yewtree Lodge, though, she really comes to life because she is a woman with a mission. Her desire to stand up for Gladys Martin is a noble one, even as Miss Marple acknowledges that the girl’s stupidity is partly to blame for her getting into this mess.

In the end, Miss Marple weaves her golden solution out of rattier straw than usual. At least we are spared one of her crazy traps, as I figure none of her usual tricks would work on Lance Fortescue. It’s a good instinct, and frankly I’m glad that our last glimpse of Lance comes before he is unmasked. The focus is on Miss Marple, and given what a charmer Lance was, we don’t need to see him snarl or crumple in the end. (The decision to have him perish after a big car chase at the end of the Hickson adaptation was one of the few false steps in that series.)

Since there’s no trickery involved this time, the problem of proving Lance’s guilt seems insoluble . . . until we are handed a deus ex machina in the form of a letter sent by Gladys to Miss Marple before her death. It basically confirms the sleuth’s entire theory, and it even contains a snapshot of Gladys with “Albert Evans” that will surely land the killer on the gallows.

My memory of this final scene was of an emotional moment for Miss Marple, but it’s slightly different than I recall.

“The tears rose in Miss Marple’s eyes. Succeeding pity, there came anger – anger against a heartless killer. And then, displacing both these emotions, there came a surge of triumph – the triumph some specialist might feel who has successfully reconstructed an extinct animal from a fragment of jawbone and a couple of teeth.”

As I said, Nemesis is on her way; here, she’s just getting started.

Score: 7/10

The Wow Factor

I gave They Do It with Mirrors a score of four in this category, based on the fact that Miss Marple appears from beginning to end. I can’t say that there is a lot about A Pocketful of Rye that is wow-worthy, but it is a better book than Mirrors. It is funnier, the servants are terrific, the use of the nursery rhyme has more purpose than usual (and works better), and while Miss Marple doesn’t appear till her usual spot in the middle, she is better served in this case, and her personal quest for justice for a young woman to whom she bore some responsibility (or, at least, felt she did) makes for a much more satisfying emotional arc than in the last book. All of this argues that my score here must be higher.

Score: 6/10

FINAL SCORE FOR A POCKET FULL OF RYE: 34/50

The character of the killer is the best part of the book for me.

LikeLike

I’ve always really liked this. There aren’t many definitive clues. One clue I remember is Miss Ramsbottom saying the mine is in East Africa while Lance says it’s in West Africa. Also, Miss Marple saying that Pat drew her attention to Lance because she’s the sort of girl who “always marries a bad lot” as illustrated by her first two marriages. It was a form of misdirection that Percy is so dislikeable and Lance so charming. Even Inspector Neele asks Miss Marple “hopefully” if the killer she’s describing is Percy, which I found amusing. I also enjoyed Inspector’s Neele’s skirmishes with Mary Dove.

I found the ending with the letter and photograph moving. As in Death in the Nile, at the very end our attention to drawn back to the victim in a poignant way, and that doesn’t always happen in Christie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are plenty of real clues in A Murder Is Announced; the rest is scattershot. The clue of the fingernails, the clue of the glass eye. Most are behavioral clues like you suggested, although I might take issue with the one about Pat marrying bad boys. There’s never any doubt about Lance being a wrong ‘un, but we also never doubt that he truly loves Pat. While I acknowledge that Christie had a very limited sentimental streak, it’s just as likely that one could put these two facts together and believe – or, at least, hope – that Lance is innocent. (Of course, those who embrace this folly are playing right into Christie’s hands!!!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think what makes me the accept the rhyme here, is that (similar to And then there Were None) it is mostly fabricated and used by the killer. Sure, Rex Fortescue’s first name is somewhat of a helpful coincidence, but it isn’t to much of a coincidence, compared to, for example, the Van Dine you mentioned. At leats not more so, than, say, Sir Carmichael Clarke’s name.

In One, two, buckle my Shoe; Hickory, Dickory, Dock or even Five Little Pigs nothing about thr rhyme is fabricated by the killer, and Christie tries to have the rhyme fit the plot by pure coincidence. It doesn’t work at all and is jarring. I don’t have the same impression here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree that Five Little Pigs is Christie’s worst use of a nursery rhyme. It’s completely out of place there.

LikeLike

When it comes to endings – not solutions, but purely the end of the novel – I think Pocket Full of Rye – ranks near the very top of Christie’s work. Those last few lines you quoted are some of my very favorite in the Christie Canon and they leave a huge impact on me.

LikeLike

Brad – I am enjoying your chronologic re-look at the Miss Marple series. What struck me so far is how few of the Marple stories would be considered genuine classics by GAD enthusiasts and yet Miss Marple unquestionably remains a beloved character in crime fiction.

Yes – A Murder is Announced is one of my favorite Christie novels of all time and I have re-read it many times, but even there Miss Marple only makes a late appearance. Yet I cannot name another that I would call an absolute classic. Vicarage, Moving Finger, and others all have wonderful strong points and your reviews show that … but I could only place A Murder is Announced along side the best Poirot novels (e.g., Death on the Nile, Five Little Pigs, Evil Under the Sun, Orient Express, etc. ),

So it is interesting that I feel that the Poirot novels yielded more classics and yet I prefer Miss Marple over Poirot as the protagonist. The idea of an unassuming, elderly spinster, who can run circles around her police detectives, is something that continues to draw me to the Marple stories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love Miss Marple as nemesis, and it’s a compelling version of her! BUT. To me (and maybe I’m too young to fully internalize the specific servant tropes here) it felt like the personal level combined with the types of clues Miss Marple used made the mystery seem less attainable – that is, she had a personal advantage above and beyond her usual life experience and knowledge of people. And I’m not sure yet h whether that makes a better or worse Marple…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Please correct me if I’m misunderstanding you: are you suggesting that Miss Marple’s understanding of servant behavior was too specialized to be considered “fair play” for the reader? For Inspector Neele?

LikeLike

I think it was probably fair play at the time! But… not as much today? I struggled pretty heavily with some of the assumptions about how Gladys “would” act. It’s one of those situations where I believe a character could act as described, but it doesn’t feel like an earned inevitability.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you have a legitimate concern here, whether we are modern day readers or not. The idea that one can assume to predict the behavior of ANY class or type of person is one we find in classic mysteries and have to take with the usual grain of salt. It can be particularly galling when it come to servants, who in this world it is taken for granted are easier to read than “real” people. One thing I like about this novel, however is how varied and well-characterized the staff is at Yewtree Lodge. The foundation is clearly laid that Gladys was a credulous girl prone to fantasy. Someone like Ellen or Mrs. Crump could never have been manipulated like Gladys was. And Miss Anatole knew Gladys very well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Like, maybe the gap is in the examples? Miss Marple will say something like, “oh well Gladys was always scatter brained, I’d keep having to remind her to AIR out the PILLOWS!” And I can cognitively understand that this is part of her job and therefore she’s missing it, but I don’t have good context for how bad it is that she forgets, because I certainly don’t have house help who airs out any pillows on a regular basis…

LikeLiked by 1 person

So many of Christie’s killers are suave, charmers, like Lance, Roger Bassington-ffrench, . . I always thought in her mind each of them was Archie.

Anyway, I digress… I love PFOR for many reasons, much of which was the humor and pathos. I too, thought Rex was most like Simeon Lee. Of anything I thought the Elaine character superfluous and empty. So was her fiancée. In the teleplay, they just cut those characters out, no loss.

Good review. I didn’t miss Miss Marple till she appeared, that’s how good the characters were.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: RANKING MARPLE #8: 4:50 from Paddington (aka What Mrs. McGillicuddy Saw) | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: RANKING MARPLE: Settling the Scores | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX (The Blog-iography!) | Ah Sweet Mystery!