All my life I’ve loved going to the movies. I grew up in that awkward era between the movie palaces and the multiplexes, but I have to say that growing up in San Francisco meant I had lots of options. There were a few grand old theatres still around, like the Castro on Castro Street (still there but more inclined to live events), the Alexandria on Geary, and the Royal on Polk Street. There were newer theatres that gathered lines around the corner because they only showed blockbusters. And there were plenty of small art houses tucked away in alleys where a guy could relive the glory days of old Hollywood or see international films deemed financially unworthy of a general release.

When I was around 10, my mom would drop off my brother and me at the neighborhood cinema, where for a quarter admission and a couple of dollars for concessions, we could spend hours stuffing ourselves with Milk Duds, popcorn and Coke while watching multiple features, cartoons and comic shorts, coming attractions, even a newsreel. The program lasted so long that we had intermissions, which explains the classic jingle: “Let’s all go to the lobbbbbbb-y!” I can’t say every movie we saw was good, but every moment spent in the theatre was special.

That special feeling has faded a lot in recent years – and not just because of the pandemic. The streaming services that everyone is currently yelling about have also contributed by limiting theatrical release and forcing people to tack on additional fees to their exhorbitant cable bill in order to watch a theatrical release on a smaller TV set. It ain’t the same. In fact, I know that some films which are given a brief premiere in a cinema are televised on a wholly different format which decreases the audio/visual quality of the experience. (Kenneth Branagh’s Death on the Nile is a case in point.)

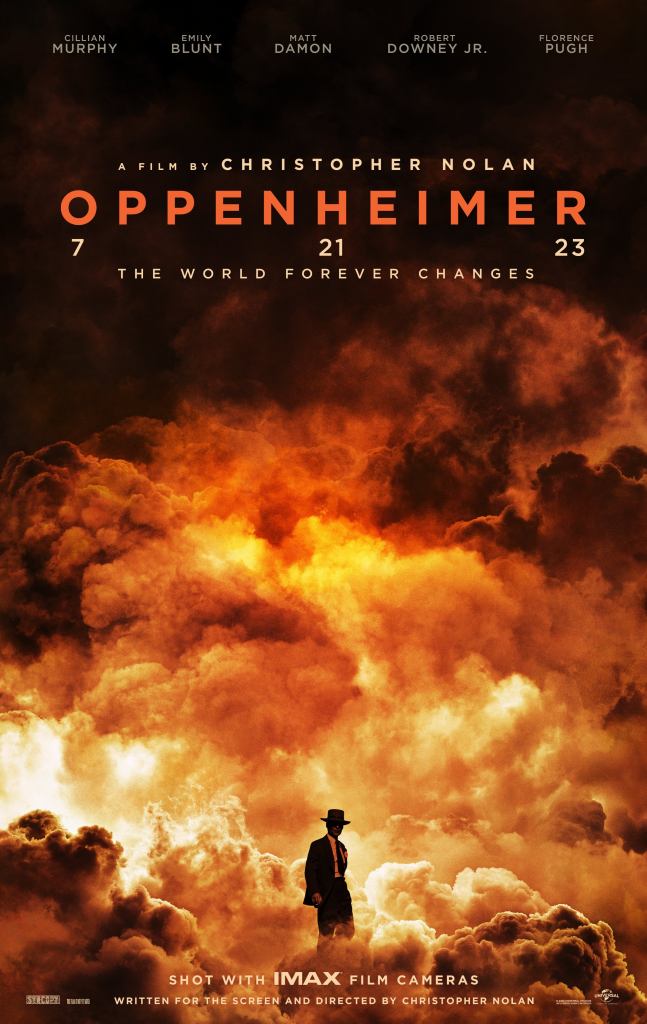

I miss the experience of standing in line for over an hour to get into a prestige production. I remember doing it for every musical I ever watched, including Mary Poppins, The Sound of Music, Camelot, and Funny Girl. Hell, I miss having a wealth of movies come out that I want to even see! So it was with great excitement that I accepted my friend Stephanie’s invitation to be part of the “Barbenheimer” experience! It certainly isn’t unusual for multiple films to open on the same day, but since Greta Gerwig’s Barbie and Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer have been touted for months – and since they seem to be such contrasting films, both in style and content – some genius in publicity spread the idea of filmgoers buying tickets to see both movies on the same day!!

Yeah, the Age of the Double Bill is long forgotten!

The hype spread throughout the general public, and the studios certainly hoped that “Barbenheimer” would result in a boffo box office. Well, let me say that if it does, it will not be due to the contributions from the Century 20 in Redwood City, California. I would guess that there were about thirty people in the 11:00 showing of Oppenheimer (which I have to admit was five times as many people as I sat with at last week’s matinee of Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning, Part I), and there were probably a little over half that many at the 2:35 showing of Barbie. Granted, some of this might be due to the recent remodel at the Century where every seat is now a glorified throne. I hate those seats. I feel dwarfed in them. I have to lean them back or else I’ll slide off the slippery surface. I didn’t know they come with cooling jets until the end of Oppenheimer where I nearly froze to death, and then Stephanie showed me how the seats warm up, too, and that was even more unpleasant.

Despite the fact that we were in for five hours of movie-going, both screens showed extensive coming attractions. The only movie that looked appetizing was Alexander Payne’s upcoming film The Holdovers, starring Paul Giamatti as a curmudgeonly schoolteacher. At last, a film I can relate to! As for the rest of the movies, this seems to be Jason Statham’s year, and I couldn’t be more pleased for him. Looks like I will be spending most of the autumn curled up with a good book.

The great appeal about Barbie and Oppenheimer opening together seems to be their differences. They are both about an invention that caused massive disruption and ultimate change to our society, but I guess they are total opposites in every other way. Although I saw it second, I’ll start with Barbie. There are some wonderful people on that screen doing fun stuff. Margot Robbie makes a wonderful Barbie – well, a wonderful Stereotypical Barbie; turns out that in Gerwig and Noah Baumbach’s screenplay, most every woman plays some incarnation of the doll, while most of the men make a rainbow assortment of Kens. Ryan Gosling is the Uber-Ken, and he’s a wonderful match for Robbie. Helen Mirren plays the Narrator and, sight unseen, gets the funniest line in the movie. And my favorite performer was America Ferrara as the only human woman in the film, who gets the plot rolling and delivers a great monologue that lays out what Gerwig is trying to say about Barbie’s position both as a shaky representation of idealized womanhood and a conduit for little girls’ dreams, with the proviso that some of those dreams have been manipulated by men.

The film looks terrific and is crammed with jokes centered around Barbie-lore, some of which I have to admit my friend Stephanie needed to explain to me. But the whole mythology of the film is a bit of a mess. In The Wizard of Oz, which you can’t help but think about frequently while watching this, Dorothy says, “My, people come and go so quickly here.” With the amount of character movement back and forth between Barbieland and The Real World, picture Dorothy’s statement on steroid overdrive.

The story introduces us to Barbie Land, a perfect-in-pink world where the Barbies rule and the Kens live to get their attention. That perfection is spoiled one day when Barbie begins to think dark existential thoughts. She consults the town witch, a.k.a. Weird Barbie (a funny Kate McKinnon) who tells her that the answer lies in the Real World. And so Barbie jumps into her pink convertible and heads to Santa Monica, only to discover that Ken has stowed away to be with her. They drive through a desert landscape that, for some reason, reminded me of Los Alamos and then take many Barbie-centric vehicles that get them to California. What they discover there is better left for you to find out by watching the movie. Suffice it to say that there is some sort of psychic connection between the dolls’ world and the real-life owners of those dolls. Some of this is played for laughs and some of it is meaningful. Some of it works, and some of it is, well, over-complicated.

I’m happy about The Real World because it brings America Ferrera into the story as a dissatisfied Mattel employee at odds with her teen daughter. I’m less thrilled because we also get a subplot about the president of Mattel (Will Ferrell) trying to do . . . well, whatever the heck he is trying to do. This man and his minions are played for laughs, but I was ice-cold immune to their charms, and the storyline led nowhere. Similarly, Michael Cera plays a doll named Allan (I’m assured he really existed) who was discontinued long ago and lives a miserable life in a world of Kens. Given how funny Cera can be, it was a shame that this subplot, too, petered out.

So, evidently, did the interest of half our audience: the entire row to the left of Stephanie was occupied by a party of tween girls who grew increasingly restive as the film went on until one of them cried out, “I’m bored.” This was the signal for those little harpies to chatter through the rest of the movie. I would have scolded them, but I was sympathetic: this is not the film they were probably expecting. Rather, it’s targeted to all the former tweens of twenty to fifty years ago, the women who, like my friend and the ladies to my right, chuckled throughout, who all had a “Weird Barbie,” that they played too hard with, who had the patience to act out scenarios with the car and the dream house and the multiple accessories, who remember Allan and Pregnant Midge and the Barbie that had a camera in her eye and a little TV in her back!!!

I accept then that I am not the target audience – although I will spend two hours any day staring at a shirtless Ryan Gosling doing a dance number with his male friends. Still, I suspect that Gerwig didn’t play completely fair with Barbie’s history, that some of the backstory of Barbie Land was jacked to fit into a directorial message that kept changing plot directions and veering back and forth between raucous comedy and touching dramedy. Maybe I’ll watch it again another time and enjoy it more because there is a lot to appreciate. And next time I’ll make sure I haven’t just come out of the three-hour screening of a film about the creation of the atomic bomb.

* * * * *

Barbie is just under two hours long and sometimes felt longer. Oppenheimer clocks in at three hours and . . . oh, who am I kidding? It feels like a long movie. More importantly, it feels like a huge movie. There are 79 credited actors playing a part in this, and I’ll admit that sitting in Row D of a D-Box theatre where my seat growled throughout the movie, I might have gotten a bit confused here or there about who was who. But I figure I can get that sorted out and watch the movie again because Oppenheimer is an experience that bears repreating.

One of my favorite Christopher Nolan films is Dunkirk where the director delivers agonizing history three ways: by land, sea, and air. Nolan is one of our great auteurs who never lets you forget you’re watching a movie, even as you get lost in the story. With Dunkirk, I felt for the soldiers and politicians trying to survive and win, even as I marveled how each segment of storytelling intersected and merged with the others. The narrative structure of Oppenheimer is even more complex, veering back and forth in time as it comes at the history from two perspectives. First, of course, is that of J. Robert Oppenheimer himself (Cillian Murphy) who emerges from his studies to both teach and build this terrifying thing, then tries to warn the world about it, then pays for his moral turnaround by being brought up on charges of treason and stripped of his security clearance. Then there is Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), former chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission who went from being Oppenheimer’s boss to his nemesis. The scenes of Oppenheimer facing the commission investigating him parallel those of the Senate sub-committee considering President Eisenhower’s nomination of Strauss for Secretary of Commerce.

Nolan switches us back and forth between these meetings and interweaves Oppenheimer’s biography through all of this. He switches film stock to help us out, but the result is a dizzyingly complex narrative that may occasionally have the feel of a history lesson but is nonetheless intense, scary and ultimately moving. It is a film about intellectuals who enter into a partnership with the American military to end a war and save the world. As the atomic bomb inches closer to reality, you can see the shifting emotions of excitement, doubt, and fear cross the faces of men on both sides.

It’s hard to find a hero here; in fact, it’s easier to describe this or that character as less villainous in the context of what they wrought. But Nolan, whose screenplay is based on a definitive biography by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, lets us view most of these characters from multiple perspectives. Thus, Matt Damon, as Lieutenant General Leslie Groves, an engineer and military man who hired Robert to lead the Los Alamos project, is both a military hothead and manipulator who then becomes Oppenheimer’s ally; Emily Blunt as Robert’s wife Kitty comes off alternately as coldly patrician and sloppy drunk until she turns into a fiercely protective wife. Cillian Murphy, who barely exits the screen for the film’s running time, is extraordinary in his ability to project the tortured soul that existed within Oppenheimer even during his moments of greatest certainty. And Nolan plunges the audience right inside that torment with blasts of imagery and sound that I’m still trying to shake off a day later.

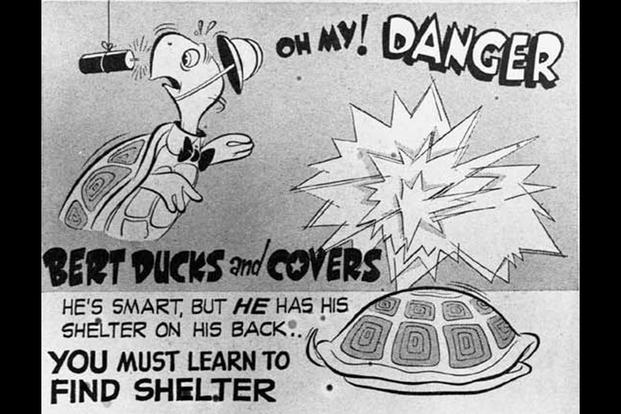

Oppenheimer is an epic film about the hubris of man and what he has wrought. I think most of the audience with whom I sat were too young to remember those school drills where we were instructed that a hiding under a wooden desk would protect us from a nuclear explosion and not to forget to hide our eyes because that flash is bright. (That “Duck and Cover” cartoon was almost as cute as “Let’s All Go to the Lobby!”) We also understand the motivation of Jewish intellectuals trying to stop Hitler, but it’s hard to give anyone a free pass from the perspective of our modern day where unstable leaders cavalierly issue threats about dropping The Bomb on their enemies as if that will solve a problem.

Nolan covers that with some frightening imagery at the end, but he also focuses on the human toll The Bomb takes on its inventors. There’s a wonderful scene at the center of the film when Oppenheimer gathers all the employees together at Los Alamos to give a rousing speech celebrating their success. It disturbs us greatly and then catapults us into the final act. Frankly, as upsetting as some of the imagery was, I’m grateful Nolan chose not to show any war scenes of nuclear horror – although some of those younger audience members I was with expressed their disappointment in the men’s room afterward that they didn’t get to see Nagasaki blow up.

Threading through this grand history is the conflict between two men, Oppenheimer and Strauss, and the light it shines on the merging of the political with the personal is also illuminating. The source of Strauss’ loathing of Oppenheimer is deeply personal and, ultimately, ludicrous, even as it leads to world-shaking consequences. Having watched the childishly savage lashing-out of ex-President Trump at his enemies for the past six years, it was easy to follow how Strauss devolves into the film’s most obvious villain, even if historically this may not be entirely fair – and even if the film is bursting with villains. (Gary Oldman, like most of the wealth of actors appearing here, was unrecognizable to me, but his brief turn as President Harry Truman is chilling and brilliant.)

Maybe the use of the word “villains” is unfair. Ultimately, these folks – the scientists, the soldiers, the spies – all were trying to do what they thought was best for their world. It’s just that their thoughts didn’t extend far enough. They couldn’t – or wouldn’t – project past the immediate future to see what a frightening and uncertain world they were creating for their children. Or maybe some of them saw but felt that their present necessity mandated the risk. Oppenheimer is a brilliant historical film, but in making us confront and embrace that risk for three hours, it is also quite the horror movie.

Well done chum – I love the idea of the double bill and hope both film do really well at the cinema. I suspect the Nolan is a bit more my speed but will definitely go see both.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Both films deal with toxic masculinity and a creation that wreaked havoc upon the earth! Both have a lot of sand. You may be more attuned to BARBIE than you thought!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

So basically they’re both riffing on LAWRENCE OF ARABIA? I knew it 🤣 I thought LITTLE WOMEN was really, really good so am definitely looking forward to BARBIE.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a splendid double feature review.

Your opening comments got me recalling Saturdays at the Harding Theater on Divisadero Street, watching newsreels during the last months of WWII and going with my mom to see Joan of Arc a few years later at the Fox on Market Street.

I’m looking forward to Oppenheimer— Peaky Blinders meets Little Boy indeed.

Cheers Bill

LikeLiked by 1 person

I sat in my Grandma’s lap at the Fox to see my very first film, GIGI! Bring back the movie palaces!

LikeLike