Considering how much I have loved John Dickson Carr for the past fifty years, it never ceases to baffle me that I purposefully, and with extreme prejudice, decided to ignore the work of one Carter Dickson. It was nothing more than a childish whim, one that in 2018 I began to rectify by tackling the Dickson novels in chronological order. And I have to say that my youthful folly was a boon in disguise! Christie’s all read (and re-read multiple times), Queen’s all read, Brand is all read . . . but with Carr/Dickson, there’s a whole stack of wonderful crime fiction still awaiting me in my dotage.

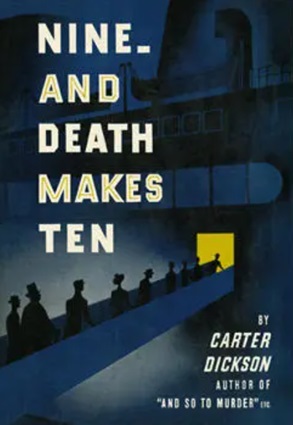

Still, I’ve been taking my good sweet time: five years into A Carter Dickson Celebration, I find myself about halfway through the canon of novels concerning the delightfully bombastic Sir Henry Merrivale, government agent and solver of impossible crimes. (He’s like Sherlock and Mycroft Holmes all rolled into one!) Fortunately, my Book Club has done right by me this month by selecting the next Dickson on my list: 1940’s Nine – and Death Makes Ten (a.k.a., Murder in the Submarine Zone, a.k.a. Murder in the Atlantic). Like its predecessor, And So to Murder, also published in 1940, this is a wartime mystery, but while one is a hilarious, light-as-air salute to the British wartime film industry, Sir Henry’s latest adventure is a white-knuckle thrill ride.

It is January, 1940, and the luxury liner Edwardic has been commissioned by the British military to carry several tons of munitions from New York to an unnamed British port. The Atlantic waters are infested with German submarines and the discovery, just before the ship set sail, of time bombs planted in the hold proves that the Nazis are aware of this valuable cargo. It is up to the crew to navigate the ship through enemy waters (the “submarine zone”) and deliver the weapons safely to the British military.

Since the mission is so dangerous, it would make sense to refuse passage to any non-essential personnel, but nine “civilians” have been granted permission to make this perilous crossing. Among them is Kenwood Blake, – sorry, that’s John Sanders – my bad! Max Murray is latest “eyes and ears” of the moment (I have written more extensively about that here), and as a Watson and stand-in for Carr himself, he is an exemplary specimen of the breed. Like Carr, who took a similar voyage during wartime, Max is a writer, a British newsman who until recently worked for a New York paper. Then an accident at a fire he was covering cost a colleague his life and landed Max in the hospital for a long, painful convalescence. Now jobless, he wants to head back to England as quickly as possible to put his journalistic skills to use in the war effort. It just so happens that the captain of the Edwardic is Max’s older brother, and while Frank is displeased to see Max make such a perilous trip, he decides to employ his brother’s journalistic skills for a worthy cause. Frank informs Max about the planted bombs and then enlists his sibling to watch his fellow passengers for signs of espionage or other suspicious activity.

Just what sort of person would skip the safe, if longer, transatlantic routes for such a crossing? As one of Max’s fellow passengers sums up: “They must have pretty strong reasons, all of them, for wanting to get to England in a hurry . . . Look at the safe sea-routes. But if you’ve got to go clear down to Genoa or Lisbon, and then come back overland, that takes time. If they’re risking this box of dynamite rather than do it, they’ve got good reason to. What I mean is, there must be some very interesting people aboard.”

The passenger list makes for a promising cast of suspects: a jovial, overly gossipy American, a bright young thing with a temper, a sleepy West Country rubber stamp salesman, a solitary French officer, a droll doctor, and a foppish aristocrat suffering from mal de mer. All the men would agree that the stand-out passenger is a voluptuous woman with the exotic name of Estelle Zia Bey, whose cabin lies directly (and conveniently) across from Max. She is one of Carr/Dickson’s minxes, albeit a slightly older one: “The woman’s attractiveness was instantaneous. Max felt it. Yet there was something vaguely unpleasant about her face: something like a small, mean wrinkle past the mouth.”

Much against Max’s will (he is only a man, of course), he and Mrs. Zia Bey engage in a tense flirtation, which amuses the other men and annoys the ship’s only other female passenger, Miss Valerie Chatford. If you can’t tell from the instantaneous dislike Max and Valerie feel for each other that they will be partners for life by story’s end, then you have no sense of the rules of screwball comedy, a genre that Carr/Dickson often taps into to enjoyable effect! The author mines even this aspect of the novel for suspense, weaving their romantic travails expertly into the murder plot.

For, of course, a murder occurs, with the crime scene awash in blood, and the killer has foolishly left his prints all over the room. With great expedience, the fingerprints of every passenger and crew member are collected – only to find that the prints at the murder scene match those of nobody on board!! But this is impossible! Who is nearby who can handle such an extraordinary situation??? And who is that mysterious ninth passenger hidden from view? Were you ever in doubt it would turn out to be the One and Only? The question is, can Sir Henry Merrivale unmask an invisible killer before the ship docks in England? For that matter, will the Edwardic even survive its crossing through the submarine zone before he reaches a solution?

Nine – and Death Makes Ten is enjoyable from start to finish, and Dickson really ramps up the tension with the double danger from an increasingly desperate killer and the growing threat of torpedo strikes as the ship nears England. HM is funny without being ridiculous, and the humor engendered by his tussles with the ship’s barber even lead to that “aha!” moment of intuitive insight we always enjoy. Also, we do not spend too much time with Sir Henry pontificating one false theory after another, as sometimes happens; instead, there’s a nice balance of focus between our detective team and the other passengers, which provides a better display of characterization than usual.

The solution, when it comes, is extremely clever and wildly improbable in the way that GAD masters could be. My only quibble is with the clues: there is simply too much stuff here that, as a mildly intelligent and well-read person living in 2024, I couldn’t possibly know. I grant you there are “traditional” clues that deliver the goods. But the whole fingerprints thing and a few other matters rely on information that must be given to all of us laymen. And Carr has a way of pulling motives out of his hat and dropping them into our laps at the end with nary a hint beforehand.

No matter: this one has to rank in the top tier of the dozen HM mysteries I have read so far. True, for once the dabbling into impossibilities is relatively minor, but the book scores both for its puzzle and for its suspensefully rendered wartime setting. I believe the emphasis on WWII diminishes beginning with the next title, but I have to say that 1940 was a very good year for Carter Dickson.

Glad this went well. I love it. It’s a terrific piece of entertainment with a great premise and the solution to the whodunit always fools me!

LikeLike

This is a great ready and I find a bit of comedy in reflecting back to key scenes. Unfortunately, you’ve hit the end of peak Merrivale with this one. That first run of 11 novels is unsurpassed in Carr’s career. The books going forward are perfectly readable (except The Cavalier’s Cup) and enjoyable, but they just never reach these heights again. Well, I suppose you could make the case for He Wouldn’t Kill Patience and She Died a Lady.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of the second half, the only one I’ve read is She Died a Lady, and I have very positive memories of it. I have heard your complaints about the back half; the reader is warned.

LikeLike

I enjoyed this one a lot, Brad, it is such a great setting.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: ACDC, PART THIRTEEN: “You’re Starting to Get Sleepy” . . . Seeing Is Believing | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: EVE OF POSSIBILITIES: Looking Back on ’24 and Forward to ’25 | Ah Sweet Mystery!