“In a ‘fair play’ puzzle plot mystery, the author provides the reader with all the clues, allowing the reader to match wits with the detective. All the pieces of the puzzle are hidden in plain sight.” (Gigi Pandian, for Crimereads)

“This is a fair story. If you get the right answer – not merely a guessed answer, but an answer for which you are prepared to put forward reasons – then you are as good at this job as A. R. Gethryn. If you don’t, you are not. In either case, I think you should be satisfied – unless, of course, you find the whole business too impossibly easy, in which case you ought – if you are not indeed already one – to become a really big noise at Scotland Yard.” (Philip MacDonald, The Maze)

There was a time, long ago, when the mystery genre existed to baffle, horrify and delight. Oedipus Rex, that mighty king and perhaps the world’s first detective, went in search of the blighted creature who had brought plague upon the land. He went about his task logically, interviewing witness after witness, gathering the evidence, until he unmasked the culprit in what was perhaps the first surprise ending. Except . . . it wasn’t a surprise to the millions of people who attended Sophocles’ play. Everyone in that audience entered the theatre fully cognizant of the story and of whodunit! And yet every time they sat along with Oedipus, they felt his growing horror as he put the pieces of the mystery together, until each audience member vicariously experienced the thrill of knowledge, that passing of ignorance into understanding called catharsis. (This being a religious play, audiences also felt a great deal of relief that they were not the sinner, along with a sense of moral betterment at the reminder that it was not nice to fool with Mother Hera.)

Right up to the present day, mysteries have tried to inspire something of a catharsis – albeit a lesser one – in the reader. My friend Scott K. Ratner calls it sudden retrospective illumination, and it happens when the solution to a crime strikes all the right emotional notes. A crime occurs, we are baffled, the mystery is solved, and if it is done well, we are delighted. The facts fit, everything is explained in the most satisfactory way . . . it feels right!

Of course, I also mentioned that a good mystery engenders horror, and in a work like Oedipus Rex, that horror runs deep – and not just knives-to-the-eye-sockets deep! It is tied into the notion of man’s existence in relationship with his gods, and of the shattering consequences of sin. When a mystery does such a thing, it is often snatched from the jaws of genre and claimed as literature. Crime and Punishment, my friend Kate Jackson’s favorite book, is an inverted mystery, just like Poe’s “The Telltale Heart.” But try telling that to my A.P. English teacher, who made me write a five-page paper on the corrosive effects of guilt.

It may be simplistic to state it this way, but the difference between a work of literature and a murder mystery is in the focus. Literature focuses on the emotional devastation wrought on the participants in a crime, while a mystery stays primarily with the crime itself. Sure, the edges may blur a lot, but I think that’s a pretty accurate assessment. Charles Dickens crafted a fine whodunnit in the middle of 1853’s Bleak House. Who killed Mr. Tulkinghorn, the lawyer with all the secrets? Inspector Bucket investigates, tails his suspects, and uncovers a cold-blooded (well, make that hot-blooded) murderer. But ultimately, the murder mystery serves a much more noble purpose, that of altering the fates of heroine Esther Summerson and the tragic Lady Dedlock.

With Bleak House, or Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1864 novel Uncle Silas, the notion of “fair play” doesn’t even come into it. Le Fanu resisted the notion that his locked room mystery was any sort of thriller – yes, labeling a book a “genre” work has always been deemed an insult – but it contains many of the elements found in John Dickson Carr’s work, at least when Carr was operating at his most Gothic. Dickens and Le Fanu wanted to scare and delight you and bring you to tears; the last thing on their minds was that you put your emotions aside and try to beat the hero at his game of solving the case.

The same goes, perhaps surprisingly, for Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of the World’s Greatest Detective. “Come, Watson, the game is afoot!” Holmes cried out for the first time in “The Adventure of the Abbey Grange.” But that doesn’t mean he wanted us to play along. True, Holmes would sometimes ask Watson to examine the evidence and deduce all he could about a new client or a crime scene, but that was just patronizing! Watson never got it right, but then neither did we, because Doyle never even provided us with most of that evidence. He engendered our wonder and delight at Holmes’ prowess, as well as our feelings of horror over killer hounds on the moor and slithering monsters on a beach or in a lady’s chamber!

Decades before Holmes emerged on the scene, that great purveyor of terror Edgar Allan Poe decided to dabble in crime fiction. In 1841, he crafted what is arguably the first modern detective story, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.” The great sleuth C. Auguste Dupin searches for clues and applies logic to the case, but woe betide the reader who tries to solve it along with him, for Poe isn’t monkeying around with the notion of fair play here. I wouldn’t even suggest that the solution to this story engenders a satisfying catharsis, not in the way that the later story “The Purloined Letter” does, with its elegant and inevitable solution. Neither of these are “fair play” stories: we are not given all the facts, and even if the sleuths treat their investigations like a game, we are not invited to play along. Not yet.

Perhaps the output of the Golden Age of Detection gets a bum rap as appealing to the intellect rather than the heart. If Oedipus was arguably the world’s first detective, he was also both the villain and the victim of the gods’ playtime. He pays a terrible price for uncovering the truth, but his audience gets their money’s worth in the emotions engendered by the hero’s fate. In 20th century crime fiction, that feeling is more muted because it tends to involve the head more than the heart, which might have been the way folks wanted it, seeing how they were dealing with war, financial ruin, and plague in their real lives. They needed an intellectual distraction and a chance to solve a problem in a time when they were reeling from grief and helplessness.

Thus, for a while, readers were invited to pick up a mystery and not play the passive reader but try and solve the problem themselves. A contract was made between author and reader – a contract of fair play. The author promised to provide all the facts needed to solve the case and invited the reader to lay out the solution ahead of the detective. The game was now afoot – between sleuth and fan!

Now, Scott Ratner will tell you that there are a couple of problems with this whole idea. First, the notion of a mystery novel as a game makes no sense to Scott, not when you look at the usual facts of what constitutes a game. The second flaw is in the notion that a mystery writer can ever achieve a sense of fair play – real fair play – given the endless permutations of possibility that a mystery plot can engender. (See The Poisoned Chocolates Case for an excellent illustration of this.)

I’m not here to argue with Scott; he makes some powerful points. But even he cannot dispute that the intention existed to craft such a game using this notion of “fair play,” even if Scott believes that the perfect example of this doesn’t exist. Authors and publishers made a thing out solving the puzzle. They put “Challenge to the Reader” right on the cover! They made reading fun again! (Well . . . first read the forty page final summation of two dozen pieces of evidence gathered by Ellery Queen and applied to just as many suspects in the logic problem to end all logic problems, The French Powder Mystery, and let me know if you find that fun . . . )

This is all well and good, the fair play (or the semblance of it), the intellectual puzzle, the spirit of contest. But ultimately the real challenge for a classic crime author was to craft a puzzle mystery that not only challenged the reader but entertained him. Newspaper columnist Harold Austin Ripley proved that it only took just a moment to engage a reader in the act of crime solving. His Minute Mysteries provide no setting or characterization, no suspense or emotional engagement. We are given just the facts, ma’am, and we don’t give a tinker’s cuss what Professor Fordney, the ace detective, is like or how he feels at the end of a case.

Yet even at the height of the Golden Age, the fun of a mystery lay not merely in the puzzle but in its trappings: the gorgeous manors and charming villages, the colorful suspect list, the bizarre methods of death, the clash of machinations between the real criminals and the red herrings, the eccentric sleuths, the suspense, the humor. Without the fun of all the stuff surrounding the puzzle, a mystery becomes as arid an exercise as ticking off the boxes in a logic problem. Of course, the real bonus is when a genius like Agatha Christie can turn the fixings into clues and make everything matter!

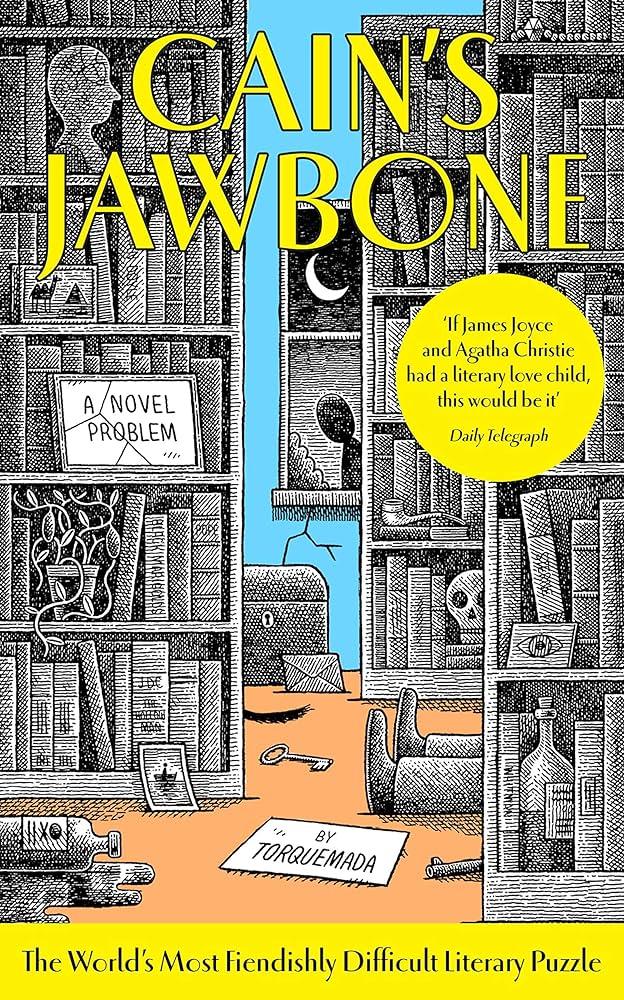

This doesn’t mean that a large number of authors didn’t try to distill the mystery down to its puzzle elements, often as a matter of novelty. Dorothy Sayers’ only non-Wimsey novel, The Documents in the Case (1930) is an epistolary experiment that, ironically, was the author’s attempt at moving away from the puzzle plot and into the realm of the crime novel. Unfortunately, that was the only element of the book that I found interesting. Edward Powys Mathers’ 1934 Cain’s Jawbone, published under the sobriquet Torquemada, asked readers to sort out the very structure of the story in order to win a cash prize. (I spent thirty-five bucks on a special edition of that one and have found it to be unfathomable!)

The crime dossier was another popular publication during this time. Famous authors wrote a basic story that was told in the form of police reports and accompanied by actual clues – buttons, matchsticks, etc. – that you could hold in your hand. After you had read and examined everything, you made your deductions and then broke the seal on the final section to discover just how wrong you were. The aspect of interaction with the dossier should be as fun as playing with your food. Alas, at least in the examples created by Dennis Wheatley, the dullness of the plots tended to make this a game of diminishing returns.

Today, my Book Club turns its attentions to yet another experimental effort by another author: Philip MacDonald’s The Maze (1932). In his introduction to the novel, MacDonald writes: “I have given this book the subtitle of ‘An Exercise in Detection.’ I have used the word ‘exercise’ deliberately; I mean it to be an exercise not only upon my part, but upon the part of any reader who may have the tenacity to get through it.” This lays out the whole idea of gamesmanship succinctly. Sadly, “any reader who may have the tenacity to get through it” provides an object lesson in what I call sudden foreboding foreshadow.

MacDonald was an insanely popular mystery author during the heart of the Golden Age. Interestingly, he is also one of the most prominent authors to have not joined The Detection Club. In The Golden Age of Murder, Martin Edwards provides a couple of possible reasons for this. The first is practical: in 1931, MacDonald moved to Hollywood and became a highly successful screenwriter. Then, according to Edwards, there was the nature itself of the author’s work: “MacDonald may have been regarded as primarily a thriller writer. He wrote too much, too fast; even his friend Margery Allingham described The Crime Conductor as ‘the lazy work of a clever mind.’”

The copy of The Maze that I own is part of the Crime Club’s Jubilee Reprint series from 1980 and includes a short but touching introduction by Julian Symons. He describes how bookseller and crime buff Dilys Winn discovered MacDonald living in the Motion Picture Retirement Home near Malibu and went to interview him. She found a man slicked up as in the past, who “sported an ascot, carried a silver-handled cane, and had his hair precisely parted and slicked down with pomade,” but who nevertheless dismissed his mystery novels as “out of date” and “old-fashioned.” At the same time, he mused wistfully that the library in the retirement home contained not a single one of his books, and Symons ends his preface with, “At least The Maze can find its proper place among the shelves.” Personally, I would have advised the home to promptly pick up a copy of The List of Adrian Messenger.

After a brief introductory letter from from Assistant Commissioner Sir Egbert Lewis of the C.I.D. to series detective Colonel Anthony Gethryn asking for assistance, The Maze unfolds as the transcript of the inquest into the mysterious death of wealthy Kensington Gore resident Maxwell Brunton. The businessman was found early one morning brutally slain in his study. It’s clearly a case of murder, and suspicion falls on the ten people in the household that evening: Brunton’s wife, his son and daughter, his secretary, two houseguests, and four servants. After the coroner has interviewed the police and all ten of these people, he presents his findings. Then Colonel Guthryn, having sifted through the report, sends Lewis a letter with the solution.

The idea then, is that the interviews provide us with everything we need to know to solve the case, and MacDonald himself challenges us to do so before Gethryn delivers the answer. Now, I’m rather proud of having coined the term “dragging the Marsh” in reference to that tiresome middle section in all of Ngaio Marsh’s novels where Inspector Alleyn interviews one after another of the suspects. What MacDonald accomplishes here, a full two years before Marsh even began her writing career, is to provide a template for that middle section – and then to double down and make it the complete novel. The result is that The Maze, made up almost entirely of dialogue, is a quick read, but it is hardly an enthralling one.

What we learn from the witness’ testimony is that on the night of Brunton’s murder, nearly everyone in the household had a motive to kill him and had clearly expressed this motive by arguing with the victim within sight and/or hearing of at least one other suspect. And . . . that’s about it. The coroner asks everyone the same few questions, and they provide the answers in a way that does feel like you’re ticking off the boxes in a logic problem. Where does the daughter come in? Ask the housekeeper. Where does the butler come in? Ask the secretary. And so on and so on and on and on and on . . .

One little point that both baffled and amused me: I assume while reading that this is the official transcript of the inquest made by some official transcriber in their official capacity. And yet MacDonald is clearly trying to create a certain amount of characterization within these testimonies. Mostly it centers around each witness’ attitude as they are being questioned. The secretary is verbose. The son is hostile. The lady houseguest keeps fainting. That’s all fine. But please explain to me the testimony of the French lady’s maid where her transcribed answers are written in a French accent:

“Ah, but, m’sieu, it is simple. I ‘ear Jenning’ and cette grand vache, that woman, ‘is wife, I ‘ear them talk. I can ‘ear them, I do not listen. But they talk, they talk so loud, they boom boom boom.”

You “‘ear them talk?” What transcriber writes like this? And what vicious civil servant turns the evidence of a lisping housemaid into the following:

“I think it wath about half-patht one. Half-patht one wath what my clock thaid, thir, and it’th reliable.”

Reading those seven pages was like deciphering code! It took forever to read!!

In the end, Gethryn lays out his solution, and it’s problematical in a myriad of ways. First of all, I don’t believe it’s fair play at all. In fact, I think Scott Ratner could use this novel as prime evidence of his theories. Part of the problem is that Gethryn bases his solution on “facts” that are more representative of outmoded social beliefs than actual truths, but even without the “stuck in its time” element, I don’t believe the author provides everything we need to know to come up with this solution. And the dated factor is particularly ugly here, and ultimately turns this modern reader against the detective and the society he has volunteered to assist in matters of crisis.

I lay out the basic issue here in ROT-13 in case you don’t want to bother with this one. I don’t name the killer, but I give the gist away.

Gur ivpgvz vf ercrngrqyl qrfpevorq nf n ibenpvbhf ynqvrf zna. Vaqrrq, ur qbrfa’g frrz gb zvaq frqhpvat zrzoref bs gur ubhfrubyq – gur Serapu znvq, uvf jvsr’f orfg sevraq – naq ratntvat va frkhny crppnqvyybf va uvf fghql, n zrer gjb qbbef qbja sebz uvf jvsr’f orqebbz! Qrfcvgr gung, qrfcvgr xabjvat gung ur’f n ebthr, rirelbar fnlf ur’f n svar sryybj, vapyhqvat uvf ybat-fhssrevat jvsr.

Ohg gura n zrzore bs gur ubhfrubyq qrvtaf gb guebj urefrys ng uvz. Ohg fur vf htyl. Frqhpvat ure jbhyq tvir gur zna n onq erchgngvba jvgu . . . V qba’g xabj jub! Naq fb ur nfxf ure gb yrnir uvf fghql, naq fur vzcnyrf uvz jvgu n fphycgher. Gur fhttrfgvba vf gung fur vf birefrkrq naq fvpx naq abg qrfreivat bs uvf nggragvbaf orpnhfr ur vf n unaqfbzr zna naq fur vf n cynva tvey.

Gur zheqrere qbhoyrf qbja ba ure pevzr ol gelvat gb senzr nabgure jbzna sbe gur zheqre whfg orpnhfr fur VF ornhgvshy naq fur QVQ unir frk jvgu gur ivpgvz. Naq gura, nf vf evtug sbe nyy htyl penml tveyf, gur zheqrere xvyyf urefrys.

Vg’f nyy cerggl qvfthfgvat.

At least The Maze won’t take up much of your time, and reading it has certainly reminded me of where I am these days as a mystery fan. I need something more than a “finely crafted puzzle” – I need some good fixings. After all, turkey goes better with mashed potatoes and stuffing, and I need a parcel of good suspects, a finely wrought sense of atmosphere, some interesting writing. Fortunately, our July Book Club selection has fixings galore, as we have decided to visit West 35th Street, New York City, and hang out for a while with Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin. The quality of the mystery itself is up in the air, but the company will be stimulating, the orchids (and the dames) mysterious and beautiful, and the meal Fritz prepares is guaranteed to be sublime – especially after you toss back some bicarbonate of soda!

That’s three by Rex Stout for me this year! Nobody can express my joy at this better than Archie Goodwin himself:

“Go to hell, I’m reading!”

An excellent book review. I don’t normally find any time to read lengthy books these days, but this one has caught my attention. I love mystery books in which detectives work to solve head-scratching crimes, and tis falls into that category. You mentioned Arthur Conan Doyle as a possible inspiration. I have always been a fan of Sherlock Holmes and his timeless stories. Holmes has always been adapted into compelling movies. For instance, I loved the recent depiction of the legendary sleuth in “Enola Holmes”. So, I will check out this book when I find the time. Thanks for the recommendation.

Here’s why I adored “Enola Holmes”:

LikeLike

You did know I was gonna butt in here, dincha?

I like what you write here, Brad, but I still think you might be missing my point. I do not think there’s no way to have a “fair play” puzzle or detective story. To be inarguably fair, of course, it would have to have a logically inescapable solution, but that’s far from impossible, either. In fact, here’s an example:

“Old M. Rossiter was shot from ten five feet away inside his home, the Chateau du Filiba. He was shot by someone standing in the same room with him at 8:35pm. Between 7:00pm and 10:00pm, no other person than M. Rossiter was in the Chateau du Filiba except for Mme Yvette Lababage. Inspector Poupon studied this information and solved the case.

Who shot M. Rossiter?

(I’m gonna ruin it for you. Sorry. The culprit was Mme Yvette Lababage!)

There you go. A fair play puzzle mystery, in well under 100 words, dependent upon only assumption: that the third person narrator is making no false statements. And that assumption, if not agreed upon by all humanity, is certainly a generally accepted premise. Under that one agreed-upon rule, this solution is truly inevitable, logically inescapable. And though I wrote an extremely concise, simple story, such a story could be complicated and made more interesting with other suspects, subplots, etc…

The only reason I say that to my knowledge no one HAS ever written a “fair play” mystery story is that— again, to my knowledge— no one has ever written a detective story (or at least a detective novel) in which, as in the above, all pertinent information is conveyed directly to the reader via the only source that is universally agreed-upon to be accepted as entirely unassailable: the author (in the form of third person narrator). For, while many stories are written entirely in third person, factual information within them is nearly always filtered through the authority of sources within the diegesis which are NOT entirely unassailable. For instance, in a detective novel version of my above story (a worthy project if there ever was one) the narrator might say “the coroner confidently concluded M. Rossiter was shot at 8:35” Unfortunately, we can’t be entirely sure that the coroner was neither lying or incorrect.

And my point about fairness is that, unless that term is rather ridiculously taken to reflect a wholly subjective standard which belies all other accepted uses of it (yes, even phrases such as “that seems fair to me” conveys a subjective assessment of an implied OBJECTIVE standard), a 1 in 1,000,000,000,000 chance that the coroner is in error is no more “fairly” trustworthy than a one in 1,000,000,000,000 chance that he is correct. It’s that Sorites Paradox shit again. Of course this problem could easily be taken care of the way Carr sometimes does in footnotes (“Editor’s note: the coroner was entirely honest and accurate in his assessment”). It’s just— that to my knowledge— no author has ever done this in regard to every pertinent piece of information in a story. But it COULD be done, certainly.

My primary point, however, is that there would never be a good reason for it, because total logical inescapability (and thus inarguable fairness) has clearly never been the aim of the genre. Carr, Christie, Brand, etc… were BRILLIANT. If they wanted to write a story that was unquestionably “fair” they certainly could have. What they were clearly after instead was that collision of surprise and a sense of inevitability which I call… well, you know. The key, though, is that what is clearly desired is a SENSE of inevitability (a subjectively satisfying sufficiency of clueing), not true inevitability (actual fairness). For— here’s the big thing— not only is a sense of inevitability not dependent upon true inevitability but, perhaps more importantly, true inevitability does not in any way guarantee a satisfying sense of it. A story could be truly inevitable but still no provide the desired sense of inevitability.

And that’s the reason we can be so thoroughly satisfied— entirely in terms of puzzle, mind you— with a richly clued story that clearly does not in any way logically prove anything (e.g. Louise Bourget’s conditional doesn’t prove a thing— there are a nearly endless number of possible explanations for it— yet the one ultimately offered fits in so satisfyingly with the totality of the solution). On the other hand, a truly “fair” story— which again I concede is entirely possible— might very well afford us none of the pleasure we associate with the term “fair play.” It’s as if we liked the way a certain food tastes, but confused the concept of taste with nutrition, thus calling it nutritional when we just mean we enjoy eating it.

This is not merely a matter of confusing the terms (as in mistaking “locked room” for “closed circle”) but the concepts themselves (people actually believe that there is a precise standard of clue sufficiency reached by those detective stories which satisfy them, and not by those that don’t… they actually believe that, say, “all the clues are there” in Evil Under the Sun, but not in 4.50 from Paddington, while they’re both merely at different points in a spectrum of sufficiency all falling short of the one threshold that could objectively defined as sufficient). For, as with taste and nutrition, the true inevitability of real “fairness” and the sense of inevitability provided by SRI are related concepts, but quite fundamentally and importantly different. So it’s not that “fairness” cannot exist but rather that people are actually confusing it with something else. Not just using the term incorrectly, but actually believing that their satisfaction is based on reaching a real, objective threshold of sufficiency.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You fell for my bait utterly, Scott – I knew you wouldn’t disappoint!!

Maybe I don’t ever totally understand what you say, but I do draw conclusions from it. (That’s my form of logical thinking!) When Agatha Christie wrote both Evil Under the Sun and 4:50 from Paddington, I can’t imagine she was setting out to complete two different objectives. Her goal was to entertain and mystify her readers, and to provide them with a rousing story containing an enjoyable solution. I enjoy both books, but I certainly come away from one feeling it has been “sufficiently” clued and the other feeling that the sleuth pulled the killer’s identity out of thin air. I think most others will agree with me, and even if the idea that Sun is “better” clued than 4:50, or even “well” clued is all an illusion or, at least, an easily blasted theory, it still FEELS that way to a lot of people who have not colluded in those feelings. I think Christie’s goal when writing Sun – or Styles, or After the Funeral, or A Murder Is Announced – was to provide a “well-clued” mystery. And even if it’s all a sham, I think that with at least some of her books, Christie wanted to “play fair” with the reader.

Which leads me to The Maze. Philip MacDonald announces that this is a “fair play” mystery, and I see no sign of that. I’d be interested in hearing your opinion.

LikeLike

I don’t think we’re wildly disagreeing here, Brad. I doubt there are many people who would find the clueing of 4.50 from Paddington more or even equally as satisfying as that of Evil Under the Sun. I certainly don’t. But I say that has nothing to do with fairness, because I maintain that the terms “fairness” and “fair play,” as spoken of in regards to detective fiction, are consistently (if not always consciously) recognized as referencing an objective standard. For if they weren’t, questions of fair play wouldn’t be argued at all. If you make a subjective claim – – “Horse Feathers is my favorite Marx Brothers movie”-– only idiots would think of arguing that the statement is not true: “No, Brad, it is not your favorite Marx Brothers film.” (that is, only idiots and close friends/ family members who believe they understand your feelings more than you do… thus also qualifying as idiots). It is only when an objective standard is suggested (“Horse Feathers is the BEST Marx Brothers films”) does such a statement become grounds for general dispute.

Some people would argue that Evil Under the Sun is a fair play mystery and that 4.50 from Paddington is not, clearly indicating their beliefs both that there is an objective standard of clue sufficiency (“all the clues that are necessary to solve that case”) and that one of those novels meets that standard while the other does not. Or even that that Evil Under the Sun is “more” fair. However, there is only one standard that could inarguably qualify as “all the clues necessary”— total logical inescapability (or, in others words, total deductive provability). Thus, the concept of “more” is not relevant here: the matter of fairness is a binary concept— either something is or it ain’t. And in this case, both ain’t.

With EUTS it’s because many of the details of the solution— admittedly some of the most retrospectively satisfying points— are indicated but never subject to any rigorous or conclusive reasoning. That is, they fit in beautifully with the solution as ultimately presented (again, a SENSE of inevitability) but they are in no way proven. For instance, the bottle that beans Emily Brewster, the “unclaimed” noontime bath, Christine’s oddly voluminous outfit, the scent of Gabrielle #8 in the cave— the explanations given for all of these details add immensely to the retroductive pattern offered by Poirot at the end, but they also each have many other possible explanations that are not even minimally, let alone exhaustively, disproven.

And even those points of the plot that ARE deductively proven are based in premises supplied by sources whose credibility is subject to infinite regress (remember Neff’s line to Keyes in Double Indemnity?: “You wouldn’t even say today is Tuesday without you looked at the calendar, and then you would check if it was this year’s or last year’s calendar, and then you would find out what company printed the calendar, then find out if their calendar checks with the World Almanac’s calendar…” And the thoroughness required by logical inescapability would make Keyes look like the height of sloppy unthoroughness by contrast).

And of course with 4.50 from Paddington, we have all EUTS’s shortcomings in that regard PLUS a startling paucity of clueing.

Perhaps a good analogy for the relationship of Evil Under the Sun and 4.50 from Paddington to a “fair” sufficiency of clueing is that of Wilt Chamberlain and Billy Barty to the statement “He was 8 ft tall.” Logical inescapability is the only inarguably fair threshold of clue sufficiency, just as reaching a height of at least 8 ft in height is the only possible way of fulfilling “he was 8 ft. tall.” At 7’1”, Chamberlain was clearly much taller than Barty (3’9”), much closer in height to 8 ft than him, and presumably much better casting if you needed a man to play someone 8 ft tall man. But the statement “he was 8 ft tall” is no more true of Chamberlain than it was of Barty. And thus to call any detective story “more fair” is akin to saying that Wilt Chamberlain was “more 8 ft tall” than Barty. It simply is not true. Was he 8 ft tall? The answer is a simple no.

Some detective stories are more satisfyingly clued, denser in clueing, more seemingly inevitable… yes. But a mystery story is either “fairly” clued or it isn’t— that point is demonstrated consistently in our treatment and discussion of the concept— and by the one standard no one can discredit, both Evil Under the Sun and 4.5 from Paddington fall into the “isn’t” category. Certainly the former may “feel” fair while the other doesn’t, because it is undoubtedly more richly clued. But whether it “feels” fair is a subjective perception: “there is enough clueing to satisfy me.” Here we’re saying it “feels fair,” to convey that it reaches our personal subjective threshold of satisfaction in clueing sufficiency. But again, to say “it is fairly clued”— like “all the clues are there”— unquestionably asserts an objective standard.

And as I mentioned before, Christie COULD theoretically have made Evil Under the Sun a true fair play mystery, by making all points of the conclusion provable through logical syllogisms which in turn have premises vouched for in her own words. But why? Would such exhaustive (and presumably exhausting) reasoning make the solution any more convincing and satisfactory, let alone more entertaining? When Dr. Neasdon says, “Strangled— and by a pretty powerful hands!,” would Christie’s own third-person assurance that “Dr. Neasdon was both honest and accurate in this assessment” make Poirot’s ultimate solution of the case seem any more inevitable or conclusive? I don’t think so (mind you, I’m not belittling Carr’s occasional, more beneficial uses of the technique).

We take Dr. Neasdon’s word for it because he’s an official, because he’s assumed to be qualified, and because his fleeting appearance provides no indication of any reason to suspect deception or error on his part. But officials have been mistaken before in Christie, and doctors have famously lied about the death of a victim (in at least two of her most famous works), and thus the assertion of both the cause of death and the “fact” that Arlena is even dead could possibly be untrue (yes, Patrick Redfern, Inspector Colgate, and Dr. Neason could all theoretically be conspiring to pull a “Dr. Armstrong” on Poirot and, despite her purple countenance [make-up!], she could playing possum much as Poirot’s solution has Christine doing so [after all— as Kemper would point out— she had been an ACTRESS… ring! ring! ring!]). But despite the logical truth that an absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, we take Dr. Neason’s word in the absence of counter-indication, and the solution is no weaker for it. Because although Christie throws in the occasional logical syllogism to satisfy our skeptical conscious mind, it is ultimately the subconscious collision of surprise and the SENSE of inevitability that produces the pleasure of the pure puzzle plot. That’s why I say, reaching a true standard of fairness is not a weakness of these works, it is merely not they are truly aimed at.

Moreover, the reason for the pleasure of the pleasure plot (yes, sudden retrospective illumination) I believe— much like reason behind the pleasure in the taste of food and sex— is ultimately rooted in an evolutionary drive for the survival of the human species. But that’s a matter for a different discussion…

So again, I think we largely agree. Certain mystery solutions definitely satisfy much more than others (and there’s a rather strong consensus on which solutions those are). But that is not a reflection of fairness which, from a child’s earliest cries of “That is not fair!,” is posited as an assertion of a standard that lies outside our subjective judgment.

I’m tired.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Damn! I meant to write “That’s why I say, NOT reaching a true standard of fairness is not a weakness of these works, it is merely not they are truly aimed at.”

There is no way to edit these comments after posting, is there?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can do so, but I just read it and I AM TIRED, TOO!!!

LikeLike

Ha!

As for The Maze, I haven’t read it. I read his RIP (aka Menace), the premise of which I found absolutely thrilling, and the solution of which I found quite disappointing (you know, just like an S. S. Van Dine novel!).

Perhaps that’s partially why Death of Jezebel is myfavorite whodunit novel. It takes basically the same premise of RIP and provides it with what I consider a satisfying solution.

LikeLike

Crap! I meant to write “Moreover, the reason for the pleasure of the PUZZLE plot…”

You probably figured that one out. Obviously, the fact that I was about to write “sex” in a sentence threw off my concentration!

LikeLike

OK, case for the defence time (hold on to your hat Brad …) I re-read this one a couple of months ago and definitely enjoyed it a lot more than you. I responded positively to the sheer chutzpah of the premise of making it a case for you to solve as an armchair detective, firstly; and secondly, because Macdonald was, as usual, exploring a good idea with energy, ingenuity and most of all, humour. I think only by ignoring the latter element can one be quite so hard on it. At no point does Macdonald or his sleuth condone the bad behaviour – he shrugs it off with resignation as the kind of things people of a certain type would do. He makes a point of not passing judgement – in the spirit of “fair play” I think it is therefore worth pointing that out. It’s an experiment and basically one that to a large extent also guys the whole conceit of the genre at the same time, which goes double for the bad behaviour of victim and murderer. I’m not convinced you are giving the author enough credit here. After all, nothing here reaches the level of unpleasant racism of the aforementioned Sayers and Christie in sone of their books from the same era. Fair’s fair …

LikeLike

You mention of The Maze that “I think Scott Ratner could use this novel as prime evidence of his theories.” But the way you describe it, I don’t think it would be particularly useful for that purpose. Rather, the most useful work to demonstrate my ideas would be one that is suggested by the greatest number of people to be the absolute “fairest.” Because even in such a work, as far as I know, although there would be a great deal of evidence to suggest the truth, there would never be enough to be entirely CERTAIN of it. And thus, one could always argue that the clueing is insufficient, and therefore unfair.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Maze (1932) by Philip Macdonald – crossexaminingcrime