Re-reading The Mystery of the Blue Train proved to be a bit of a challenge, but not for the obvious reasons. My recent bout of COVID left a going-away present in the form of pneumonia; a kitchen remodel stretched out to months, and my 60-year-old Pocketbook copy of Train fell apart in my hands while reading. Dealing with mysteries should not be so difficult! But then I thought of Agatha Christie and what she went through to write The Mystery of the Blue Train. The death of her mother. Her husband’s abandonment. She begged Archie for another chance. He came home. They were miserable. He left for good. The disappearance with all its attendant notoriety. And there was her publisher saying, “Where’s the new book?”

And so Agatha cobbled a bunch of stories together and called it The Big Four. And then she pulled out an old short story from 1923, “The Plymouth Express,” and began to expand upon it. She covered eighty-five pages over two notebooks with notes and, according to John Curran, what she described there is what you get in the finished product. She took baby Rosalind and secretary Carlo Fisher to Egypt and Tenerife to write the book. Rosalind behaved shamelessly like an eight-year-old girl. Agatha was distraught.

“I had no joy in writing, no élan . . . I knew, as one might say, where I was going, but I could not see the scene in my mind’s eye, and the people would not come alive. I was driven desperately on by the desire, indeed the necessity, to write another book and make some money.”

Some may find it easy to dump on 1928’s The Mystery of the Blue Train, but nobody did it quite as expertly as the author herself. “I have always hated The Mystery of the Blue Train,” she wrote in her autobiography. “Really, how that wretched book came to be written I don’t know.“ Some of her criticism is for the finished product itself: “I think it commonplace, full of cliches, with an uninteresting plot.” But we must imagine that some of Christie’s feelings about the book are tied into that awful time in which it was written.

Other critics and scholars down through the years have been kinder to the book. Curtis Evans calls it “very much an underrated Christie.” Kemper Donovan and Catherine Brobeck ranked it #54 out of 66, with five Poirot mysteries ranking lower. Mark Aldridge has this to say: “If divorced from its origins and read simply as a new Poirot murder investigation then there is much to admire in the ingenuity of the murderer’s plan and way it is initially presented to the authorities . . . “

If some of Blue Train feels like a tired thriller and some of the characters are stock – or worse – we must remember the time in which it was written, as well as the delight Christie took in writing thrillers. Finally, it can’t be understated how much this book represents an important lesson that Christie learned – one that I myself experienced through COVID and pneumonia and antibiotics and kitchen remodels and a book falling apart in my hands: the lesson of perseverance.

“That was the moment when I changed from an amateur to a professional. I assumed the burden of a professional, which is to write even when you don’t want to, don’t much like what you are writing, and aren’t writing particularly well.”

Let’s see what we make of it.

* * * * *

The Hook

The influence on Christie of her peer, the popular thriller writer Edgar Wallace, seems evident throughout the 1920’s, most prominently in the Tommy and Tuppence and Mr. Parker Pyne stories and in 1927’s hodgepodge of a Poirot novel, The Big Four, whichis rife with disguised villains, plans for world conquering, and bizarre death traps. Blue Train opens in a similar vein, with an assortment of dodgy characters moving around the slums of Paris, all in fear of a mysterious masked criminal called “Monsieur le Marquis” and all eager to follow the path of a magnificent set of rubies. The largest, the “Heart of Fire,” is said to have adorned the neck of Catherine the Great.

The problem with these opening chapters is two-fold: they are peopled with embarrassing caricatures, and the action is vague. M. le Marquis makes his appearance, but I couldn’t tell you in the moment what his goal is. CriticRobert Barnard refers to this as “the deleterious influences from the thrillers.” Still, it leads to the off-page sale of the rubies and the introduction of a whole new set of characters as we segue into a turgid melodrama involving the rich and famous, a subset of society with whom Christie usually had little interest. A ruthless American millionaire Rufus Van Aldin, his spoiled daughter Ruth, her ne’er-do-well husband and ne’er-do-well lover, the husband’s sleek French mistress . . . I’m beginning to understand Christie’s own comment about things feeling “commonplace” and “full of cliches.”

The first six chapters feel like something of a slow burn meant to maneuver the Heart of Fire into its proper place. But then, in Chapter Seven, Christie changes gears: she moves into Jane Austen territory and introduces us to the actual protagonist of the novel, Katherine Grey, whose Cinderella story is actually fun to read. And get this – Katherine lives in the village of St. Mary Mead, which was introduced to readers three months earlier in the short story “The Tuesday Night Club.” Why Katherine is not a member of this club, and why she seems to have not made the acquaintance of Miss Marple, I cannot say. The important point is that hanging out in Miss Grey’s company is a whole lot more enjoyable than anyone else we have met thus far. Even her greedy relations are fun!

In summation, it takes ten chapters to gather together the turgid rich people and the charming Austen people on the Blue Train. Throw in the possibility that Monsieur le Marquis is also onboard, as well as the presence of a striking Belgian gentleman with an egg-shaped head (who is about to get his first female assistant), and the stage is set for murder.

So what’s the hook? The jewels? Ruth Kettering’s romantic dilemma? Katherine’s inheritance? Maybe in this one, you get to Choose Your Own Adventure!

Score: 5/10

The Closed Circle: Who, What, When, Where, Why?

Who?

“Snake charmers, they say, are born, not made. Katherine Gray was born with the power of managing old ladies, dogs, and small boys, she did it without any apparent sense of strain. At the age of twenty-three she had been a quiet girl with beautiful eyes. At thirty-three she was a quiet woman, with those same gray eyes, shining steadily out on the world, with a kind of happy serenity that nothing could shake. Moreover, she had been born with, and still possessed, a sense of humor.”

This may become a running theme, but for me the quality of character depends on which narrative thread you are following. The best characters by far populate the Austen-ian world surrounding Katherine Grey, and are led by that young lady herself. You can tell by her description that Christie likes Katherine, indeed, perhaps, envies her as someone who can assess and conquer any problem.

In her biography of the author, Laura Thompson compares Katherine to Charlotte “Carlo” Fisher, Christie’s secretary-companion, who could charm Clara Miller when she was alive, earn young Rosalind’s respect, and tend to the emotional maelstrom that was Christie’s life at the time.

Although she is surrounded by scoundrels, self-servers, and fiends, Katherine isn’t an ickily-good, Fanny Price-type of heroine. She’s more like Elinor Dashwood from Sense and Sensibility: handsome and inquisitive, willing to let others take the limelight but equally curious about establishing a happy life for herself. And she does like the bad boys!

Her relations are nearly as charming, even in their flawed glory. Lady Rosalie Tamplin is celebrated for her parties on the Riviera and described in the context of her four husbands, the latest of which, Chubby Evans, is anything but chubby and half Lady Tamplin’s age. Her avarice is charming for its openness; she even proposes a fair trade of putting up Katharine to society in exchange for gold. Even her sour daughter Lenox is one of my favorite characters, one in a long line of dissatisfied young women (Rosalie Otterbourne, Deirdre Henderson, et al) whom Christie rendered so well.

The link between Katherine’s world and – oh, let’s call it the Downton Abbey-esque plotline is Derek Kettering, the future Lord Leconbury and Ruth Kettering’s estranged husband. Already a whopping thirty-four, there is still something boyish about Derek, as well as a plenitude of charm. But there is also in his voice a lazy quality and “a slightly ironic inflection” which I think mitigates any eagerness to compare him to the more earnest Archie Christie. Maybe he’s a sort of mash-up between Archie and Agatha’s ne-er-do-well brother Monty. Derek is frankly more annoying than charming throughout the book, but he is clearly redeemable by the attentions of a good woman. And that is what Christie has in mind here: the number of coincidental times Katherine and Derek run into each other is staggering.

The rest of the Downton clan does not impress me. Rufus Van Aldin is, in many ways, the typical American tycoon you find in Christie: forthright and ruthless, out for the advantage, always wary of being taken. He is described with adjectives suggesting coldness, except when he deal with his daughter, whereupon his emotions veer dangerously close to obsession. This guy is supposed to be a financial brain and a great judge of character, having got rid of the Comte de la Roche the first time and shaken his head when Ruth married Derek. But Van Aldin hires Richard Knighton on a whim to be his confidential secretary, and it proves to be a tragic mistake.

If Katherine represents the sort of person Christie would rely upon in her time of crisis, Ruth Kettering could be almost a stand-in for Agatha herself. Faced with the prospect of divorce from an unfaithful husband, Ruth sees no easy choices before her. But she has no job in which to bury herself, and so she turns to a previous unsatisfactory lover for solace. Had she survived her journey on the Blue Train, Ruth would have had to face the consequences of the Count’s con game. We don’t get much time with Ruth, and I find her dialogue to be some of the stiffest in the novel. But that may be because most of the time she is lying.

This brings us to the four villains of the piece, and they are the least satisfying of the lot. The two paramours of our tragic couple are so cliched as to feel cartoonish. The Comte de la Roche is played up as a conniving Pepe Le Pew: he cuts a fine figure and possesses a nice moustache, but we never see him in paramour mode, only as a schemer. Mirelle, the French dancer, could be a female Pepe or a Gallic Mae West:

“Mirelle was lying on the divan, supported by an incredible number of cushions, all in varying shades of amber, to harmonize with the yellow ocher of her complexion. The dancer was a beautifully made woman, and if her face, beneath its mask of yellow, was in truth somewhat haggard, it had a bizarre charm of its own, and her orange lips smiled invitingly at Derek Kettering.”

Both these characters are so over-the-top that they make no sense as distractions for Ruth and Derek, respectively; rather, they lessen the believability of husband and wife in our eyes, both of whom are too cosmopolitan to be so taken in by a fine scent and what I assume must be magnificent sexual prowess.

As for our murderers, Ada Mason and Richard Knighton, Mason is a cipher because she’s a servant, and I can only think that if Christie had performed some of her magic and created some semblance of personality for Mason, it would have made for a richer story and a better surprise. Knighton is clearly Monsieur le Marquis because – well, who on earth else could it be? It has long been my practice when reading Christie to suspect the secretary. (It happens often enough that I am even correct sometimes!) And Knighton also follows a rule found in countless mysteries: when a woman finds herself possessed of two suitors, a good guy and a bad boy, and she is emotionally drawn to the bad boy and ultimately rejects the good guy, chances are good that in the end, the good guy will indeed turn out to be the real bad boy!

Knighton is our link between the Downton world and the Edgar Wallace world. The characters that populate the latter are the hardest to take in the book. Most of them are stuck severely in their time, such as Boris Ivanovitch, who has “the least hint of a curve in the thin nose. His father had been a Polish Jew,” and Olga Demiroff, whose make-up cannot disguise “the broad Mongolian cast of her countenance. At least the Greek scoundrel, Demetrius Papopolous, effects a grandly benign countenance, but Christie can’t resist describing his daughter Zia as “Junoesque.” And I suppose we must give Christie some credit for making Papopolous a Jewish man of honor – because he owes a debt to Poirot, and the Jewish race “never forgets.” I’m not sure that Demetrius deserves a whole lot of credit, since he seems to keep his Judaism a secret, but it says something for Poirot that he takes it for granted that this man honors his debts because he is Jewish.

What?

Wouldn’t you know it that when Katherine Grey meets Hercule Poirot, she’s reading a detective story? Who knows whether her own roman policier takes its own sweet time to get going, but once Poirot invites her to join him in a true-life sleuthing adventure, the pace picks up considerably. Ruth Kettering is found dead – brutally so, as it happens, her face bashed in beyond recognition; Katherine becomes the key witness, the first woman to Watson for Poirot, and the object of every man’s romantic eye! Even Poirot looks at her with a little twinkle in his eye!

In all seriousness, though, he is assuming a new role that will become a beloved one through the years – that of “Papa Poirot,” the Belgian equivalent of Yente the Matchmaker. He maneuvers Katherine quickly into a romantic triangle between the dashing Major Knighton and the irresistible cad, Derek Kettering. It all happens too fast, but it’s worth noting that Christie is no Patricia Wentworth, she frequently enjoys employing the Rule of Romantic Triangles found in so many classic mysteries. Every scene with Knighton is breezily romantic, while each rendezvous between Katherine and Derek becomes increasingly fraught with suspicion and hopelessness. And in the RofRT, it’s never the easy choice.

We learn the circumstances of the crime, and they’re not much. Ruth has dismissed her maid back to Paris, presumably in order to complete a rendezvous with the Comte de la Roche. But the Count denies ever meeting her and produces an alibi for the time of the crime. “Oh, alibis!” snorts Major Knighton, who seems to be a big fan of Poirot’s. “You confess that you read detective stories, Miss Grey. You must know that anyone who has a perfect alibi is always open to blatant suspicion.”

Seeing that Christie provides her murderers with perfect alibis in book after book, she knows that Knighton’s opinion openly expressed will do much to disarm her readers. We fully expect the Count’s alibi will be dashed, but is it possible to really suspect this clown? De la Roche would make a most unsatisfying main culprit in any Christie novel, but it’s fun to boo and hiss him here, as when he has an assignation with Mirelle and the two of them plot and counterplot so dramatically that you can easily imagine them dancing the tango ing throughout their discussion.

Let’s not forget that Major Knighton also has a perfect alibi: he was in Paris, giving a perfect alibi to Ada Mason, Ruth’s maid. Most people will accept the testimony of this pair with alacrity: he is essentially a minor character so far, and she is – (cue music) – a servant. Unless we can find a way to place Lady Tamplin or Lenox on or near the train, perhaps disguised as a young lad in a cap and overcoat on the station platform at Lyons, then it looks like the only major suspect who could be our killer is Derek Kettering. But where would that leave us in that Rule of Romantic Triangles?

Look, it’s only 1928, and this is only Christie’s eighth novel and fifth Poirot mystery. Everything going on here is perfectly serviceable, if a bit hackneyed to most post-Golden Age readers. I had no problem with it when I was fifteen in terms of believability; I just found it dull. And that’s the real problem here: we’re on board the world-renowned Blue Train, chugging through a novel by a woman who displayed command of plot and characters from the start and only improved from there! We should expect our service to excel!

Think of the complex romances between the Cavendish boys and their ladies in The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Think of all the interesting women swirling around Paul Renauld in Murder on the Links. Think of the brilliance of the murder plot in Roger Ackroyd and the insouciant charm of Tommy and Tuppence in The Secret Adversary. In Blue Train, as long as we are in the company of Hercule Poirot and/or Katherine Grey, it feels like we are firmly in Christie territory. The alternating scenes, however – between Derek and Mirelle, between Mirelle and le Comte de la Roche, between the Comte and Derek – are filled with creaky dialogue and tired melodrama. (How tired I got of the great wafts of perfume emanating from the dancer and her goofy – how you say? – accent!)

When and where?

Blue Train is considered one of Christie’s travel books, which always promise a heightened sense of place and incident. Unfortunately, stacked up against Death on the Nile or Murder on the Orient Express or Appointment with Death, we ride the rails, party on the Riviera and skulk about Paris without ever getting much of a sense of time or place.

Christie was never a provider of extended description: most of our feelings about place come from its service to the action laid out across the landscape. But as much as these characters flit from carriages to chateaus, from slums to salons, mostly they just talk. They report things to each other, and the plot inches along. I’m making it sound dull, and it really isn’t that dull, less so to a man, er, a few years past fifteen, which should remind us once again that Christie did not write for children. But it’s . . . well, it’s a little dull.

Score: 4/10

The Solution and How He Gets There (10 points)

“’And now you have come to London to see Mr. Van Alden?’

“’Not entirely for that reason. I had other work to do. Since I have been in London, I have seen two more people – a theatrical agent and a Harley Street doctor. From each of them I have got certain information. Put these things together, Mademoiselle, and see if you can make of them the same as I do.’”

So says Hercule Poirot to Katherine Grey at the penultimate point in the novel. It’s the moment when the detective says to the Watson, “I don’t need to name the killer. You can do that yourself if you can only explain the significance of the oversized footprint in the flowerbed, the aroma of burnt hazelnuts, the chloroformed budgie, and the strange behavior of the greengrocer’s aunt.”

As far as the reader is concerned, Katherine could not possibly explain the significance of Poirot’s visits because a. she wasn’t with him, and b. she has been given no context. Heck, WE went on the visit to see the agent, and none of us could tell you what the actress Kitty Kidd has to do with the case or how Poirot came up with the name.

By this point, Katherine seems completely ambivalent about playing Watson to Poirot, no matter how many times he reminds her that this case is the real life Roman policier that they share. She has fled the Riviera and taken up a post with a new querulous old lady. But, as it turns out, Katherine is no traditional Watson; as far as this goes, in fact, Christie has broken Ronald Knox’s 9th Commandment: “The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal from the reader any of the thoughts which pass through his mind . . .” Poirot explains to Lenox that “Mademoiselle Katherine has spent a great deal of her life listening, and those who have listened do not find it easy to talk; they keep their sorrows and joys to themselves and tell no one.”

This reticence is commendable – unless you are a character in a mystery novel who is required to share certain information with the reader in order to give us a fair shake at solving the case! We witness a moment when Katherine feels strongly the presence of the late Ruth Kettering in a room; what we aren’t made aware of is that the message Katherine feels Ruth is sharing with her is that Major Knighton is her killer. And rather than flee the ardent young man, Katherine shares (in private) her suspicions with Poirot and decides to play up to Knighton in order to . . . I don’t know, catch him somehow?!?

Poirot’s own suspicions of Knighton are explainable – he spends several pages at the end explaining it all to Mr. Van Aldin – but when we think of what a brilliant puzzle plotter Christie is, the explanation is unsatisfying. It hinges on a statement made by the maid, Ada Mason, which Poirot actually misinterprets, and it involves the clue of the cigarette case with the letter “K” monogrammed on it.

For a brilliant clue of a piece of hard monogrammed evidence found near the body on a train, look no further than Murder on the Orient Express. Christie mines the handkerchief with the initial “H” for all it’s worth. The cigarette case is a poorer specimen: since nearly everyone involved in the case has “K” as one of their initials, the case outwardly tells us nothing. But when Mason suggests that Ruth might have bought the case as a gift for her estranged husband, Poirot interprets that statement as an absolute and deduces that, given the state of their relationship, Ruth would not have bought such a gift for Derek. Poirot goes even further, suggesting that this odd statement makes everything that Mason has told him suspect.

This is quite a leap, but it gives the detective the impetus to come up with the idea that Mason did not leave the train but in fact impersonated the already murdered Ruth in order to tell the conductor that she, Mason, had left the train at Paris, thereby establishing herself with an alibi. It’s a clever idea, and of course it doesn’t gibe with the statement by Major Knighton that he saw Mason at the Ritz in Paris. Once you put these two facts together, if you can, the idea that Knighton and Mason were working together starts to form.

This leads to a rush of memories about Knighton, if you’ve been paying attention, particularly the fact that wherever he goes – Lady Tamplin’s makeshift hospital, a house party he attended, the part of Switzerland where he met Van Aldin – there have been jewel burglaries. There’s also the fact that he limps while the Marquis doesn’t – a “fact” that is supposed to rule him out, but which Poirot dashes because of a chance remark made by Lenox Tamplin that the doctors had said Knighton would not limp.

It turns out that Knighton has a passion for old, storied jewels and that he conceived this plot with his confederates, the chief among them being actress Kitty Kidd, a.k.a. Ada Mason. Did nobody notice that both Knighton and “Mason” entered their employ at the same time? Evidently not. Their plan is complex but effective and manages to survive the complications of Katherine Grey’s befriending Ruth on the train and the inconvenient alibi of their scapegoat, the Comte de la Roche (an alibi that turns out to be fake, another fact that Poirot guessed rather than deduced.)

But there are problems with this solution. Why did the Marquis kill Ruth when he could have easily had the jewels stolen and remained in the background? Poirot comes up with a last-minute explanation for this: “He is a killer by instinct; he believes, too, in leaving no evidence behind him. Dead men and women tell no tales.” Okay, but how did this renowned thief with the complex plan then leave his cigarette case behind? Sure, anyone can make a mistake, but given his track record, this seems to be an incredibly foolish and unlucky one.

There are problems, too, with the delivery of information. Poirot (and Katherine) play things too close to the vest to play fair with us. The scenes with the Comte’s servants and Joseph Aarons, the theatrical agent, come out of nowhere. And there are no real suspects for us to consider, as John Goddard explains in his analysis of the case in Agatha Christie’s Golden Age:

“We don’t believe that the Comte is the murderer (he is too obviously offered up to the police.) We don’t believe that Derek is the murderer (he is too obviously offered up to the reader.) Katherine seems too genuine to be the murderer, just as Mirelle seems too temperamental. With rather too much predictability, the stereotyped suspects seem too obvious or too unlikely – other than Ada – but Knighton saw her in Paris. So we are not sure what to believe.”

I suppose the actual solution, with its hidden conspiracy, is meant to surprise us. I’m sure that it does surprise a lot of people. Although I maintain that Knighton’s exposure as the Marquis is hardly a surprise, the fact that he is actually the killer is surprising. It strikes me as an unfair surprise however, as I have discussed, and the whole solution seems shakily clued.

Score: 4/10

The Poirot Factor

It’s true that Hercule Poirot doesn’t enter the case until Chapter Ten, but once he begins to work, he shines. I may have issues with Christie’s presentation of his solution, but his methods are a delight to follow as he goes from interview to interview and takes on the persona that is necessary to get the job done.

What is especially lovely is the chance to see the real Poirot through the eyes of Katherine Grey. We know he loves Hastings, but he is always infuriated with his friend’s dumbness or infuriating Hastings with his showy methods, lack of openness, and unmitigated ego. Here Poirot is charmed by Katherine and invites her to join him in the case not to impress but to spend time in her company. He wants her life to change for the better and seems to think it will if they share their own roman policier together. He likes her enough to be impressed with her sensitivity – her feminine intuition – that leads to her suspecting Knighton and to take those suspicions seriously. (How often has Hastings plumped on an innocent person as the murderer and been met with an amused, dismissive grin?)

In a significant way, Poirot seems to treat Katherine like a peer, which is even more apparent when you compare the way he treats Lenox Tamplin. There, he is pure “Papa Poirot,” well aware that Katherine will end up with the man Lenox loves and making sure in the book’s final scene that the younger woman will get over her romantic disappointment and move on. We also see the varying ways in which Poirot deals with his suspects and witnesses, handling the smarmy Comte and the tempestuous Mirelle with ease or striking just the right authoritative note with the Comte’s servants in order to break his alibi. (How he knew they were lying, however, we will never discover!)

Most delightful are the several scenes we get between Poirot and his valet George (or Georges). There amusing dialogues together have a sort of Jeeves/Wooster ring to them, although Poirot is no airheaded aristocrat; rather, he plays straight man to George’s amusing observations of the upper classes. His snobbery actually aids the detective in solving the crime; if only George’s understanding of the viciousness of certain aristocratic hooligans could have aided the reader more!

Score: 10/10

The Wow Factor

This case is, as others have stated, far from hopeless, but it fails to wow me. Still, I’m going to go back to the beginning and give the book a few points to The Mystery of the Blue Train for the part it played in Christie’s life. There’s something to be said for a book being it’s creator’s least favorite and still being credited for turning her into a professional!

Score: 3/10

FINAL SCORE FOR THE MYSTERY OF THE BLUE TRAIN: 26/50

THE POIROT PROJECT RANKINGS SO FAR . . .

- Cards on the Table (36 points)

- The Mystery of the Blue Train (26 points)

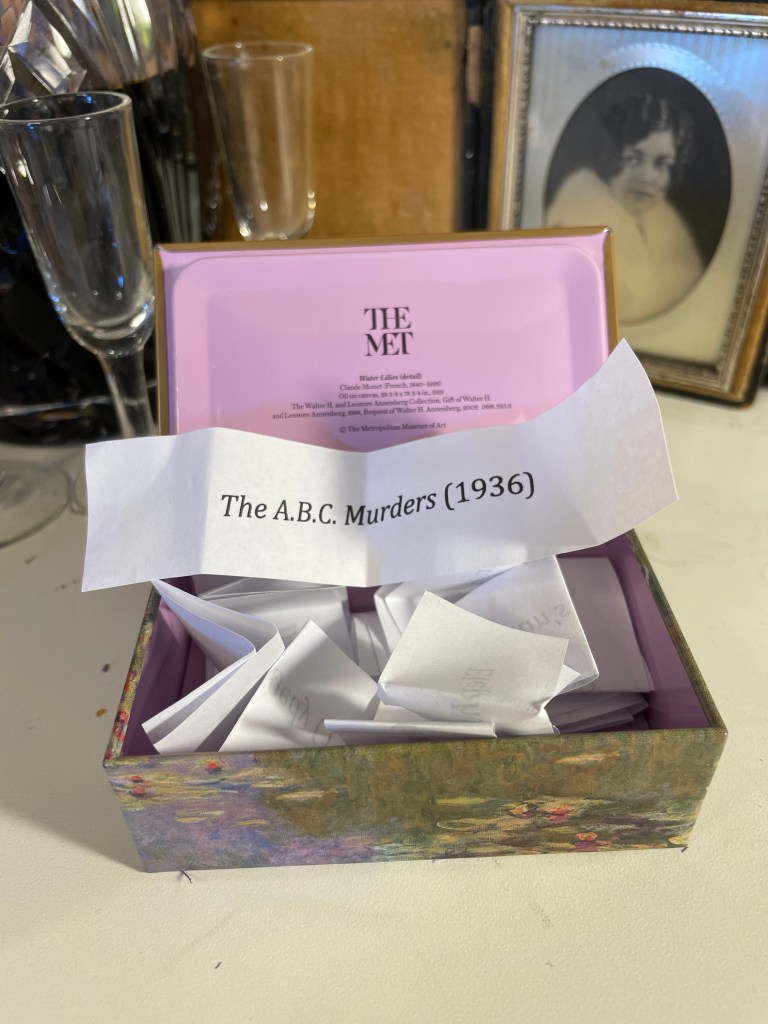

Next time, we return to 1936 and a wholly different connection to trains . . .

Most fans call this one of the best. Let’s see how it stacks up in the rankings. See you in a month.

Sorry to hear that things have been tough, Brad. I hope it’s all on the up now.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

First of all, I hope you are feeling better now and the pneumonia is gone.

Regarding this book: I like, that she made it part of the plot, that the Blue Train travels in a very slow speed around Paris. I assume this was from real life (so the train really did this) and she used it very cleverly. I think from this information we could have gotten that someone could have entered and left the train around Paris.

The lighter is IMO one of the worst clues in all of Christie. It doesn’t help at all and made the killer seem stupid.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The one time I read this, many train journeys ago, I knew none of the background… but I knew a lemon when I read one! I think you are correct throughout out here but not even remotely persuaded on the top score for the Poirot factor. Unlike your new kitchen, which clearly deserves 10 points!!

LikeLike

It wasn’t until we saw “Agatha Christie and the Truth of Murder” that we learned she was probably inspired by the murder of Florence Nightingale Shore (the famous nurse’s goddaughter). In 1920, she was killed aboard a train from being hit with a blunt instrument. The murder was never solved. One neat bit of trivia: one of the clue pointed to “The man in the brown suit,” and Christie must have filed that away for later use.

Plus, I’ll add that the “Poirot” adaptation was pretty good, helped along by Elliott Gould’s performance as the American millionaire (he was a fan of the show and approached them to see if they had a part for him), the cast of characters, and filming in the south of France.

Final note and then I’m done: Katherine Grey sounds like a precursor of Lucy Eylesbarrow from “4.50 from Paddington”: a competent woman who involves herself in murder and romance.

LikeLike

Sorry, Bill, your comment got lost in the ether of WordPress, and I just recovered it. Thanks for the info about real-crime connections. And, yes, I always thought of Katherine as a precursor to Lucy – with a similarly unsatisfactory resolution to her romantic troubles. (I mean, Lucy SHOULD have married Dermot Craddock – everyone knows that – and Katherine follows the path that others will continue of falling for a bad boy who will probably not treat her very well in the end.

LikeLike

It has been a very long time since I read this so I cannot challenge your review or, indeed, the conventional wisdom surrounding this book. Nevertheless, I think a case can be made that this is the superior novel to that earlier Poirot adventure, Murder on the Links; an opinion I believe is shared by Kemper Donovan. Blue Train *feels* like Christie; the unbreakable alibi, the least likely suspect(s); even the master jewel thief feels like one of the time-honored tropes that Christie made her own. Murder on the Links feels so indebted to Doyle and Gaston Leroux that it is hard to view it as anything other than a conscious pastiche of their work. As you say, if this is the book that turned Christie into a professional, the evidence is surely there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You won’t get any argument from me, Nick! One of the happiest moments for me was when I discovered that among the 15 novels that I had not provided reviews for on this blog so far, none of them were The Murder on the Links! I have tried to like that one, but it may very well be my least favorite Poirot mystery.

LikeLike

I quite LINKS actually and she definitely wrote much weaker Poirots than this one (like … BLUE TRAIN). But let’s meet in the middle – I get LINKS and you can keep every copy of ELEPHANTS in the universe and save the rest of us from its sheer rubbishness … 🤣

LikeLike

Murder on the Links is a far more complex mystery, more so than it’s predecessor The Mysterious Affair At Styles and Blue Train, so maybe that’s why I don’t read it as much. It’s not a bad mystery, but if you want something more a complicated, complex, and intricate mystery, then Links is it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Links has always left me cold. It feels like the most Holmesian of the Poirot mysteries, and I find it significant that after one previous case, Christie already wants to marry and ship Hastings off.

LikeLike

I think it was a wise decision for Christie to ship Hastings away instead of dragging him along in all of the novels as a Watson figure. Christie probably thought Hastings is more tolerable in appearing in the many short stories then full-length novels. Watson appearing in all of the Sherlock Holmes stories is far more tolerable.

LikeLike

Dull is very much the word that comes to mind for me with The Mystery of the Blue Train. I am so predisposed to enjoy train mysteries that one has to miss really badly for it not to work for me on some level. FWIW, I’d go so far as to say that this may be my least favorite Christie (though I haven’t reread some of the later Poirots in a while)…

I do like the way though that Poirot comes to consider the deceased, rather than the man who hired him. That struck me as quite heroic on the part of Poirot and I think that is one of the things that defines him as a detective.

I liked the idea of Katherine, but not the execution. Mostly because of the unconvincing romance storyline she’s saddled with…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, this isn’t the only time Christie will saddle a woman with two highly unsuitable suitors to choose from. In a way, I’d like to think that this was the Miss Marple origin story, but there’s no reason why she would have changed her name from Grey to Marple.

LikeLike

I can understand a lot of your criticisms, and can’t really argue with them, but I still like this one much more than most people do. Like you, I read it as a teenager and thought it was glamorous and romantic beyond words. I now see it quite differently, but still enjoy it. Of course there is an excellent transformation scene where Katherine buys new clothes, always a favourite round here.

And (even more than Orient Express) it gave me a taste for train travel – every time I’m on a train pulling out of a major European city I get a tremendous thrill, reaching right back into Christie’s books. And when we stop at a darkened station in the early hours, I look out the window just in case there is a slim figure in an overcoat and cap either getting on or getting off…

LikeLike

I can understand a lot of your criticisms, and can’t really argue with them, but I still like this one much more than most people do. Like you, I read it as a teenager and thought it was glamorous and romantic beyond words. I now see it quite differently, but still enjoy it. Of course there is an excellent transformation scene where Katherine buys new clothes, always a favourite round here.

And (even more than Orient Express) it gave me a taste for train travel – every time I’m on a train pulling out of a major European city I get a tremendous thrill, reaching right back into Christie’s books. And when we stop at a darkened station in the early hours, I look out the window just in case there is a slim figure in an overcoat and cap either getting on or getting off…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course, I don’t have your experience with train travel, Moira. But I did take a train to Torquay this past fall, and my experience was a bit different: on the advice of many friends, I snagged a window seat, but when I arrived, I discovered that my window seat was wet! I ended up sitting on the aisle next to a woman who was giving loud advice over her cell phone through much of our trip. Sadly, I saw no evidence of a woman in a scarlet kimono anywhere!

LikeLike

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX (The Blog-iography!) | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #3: The A.B.C. Murders | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #4: Dead Man’s Folly | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #5: Three-Act Tragedy | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #7: Death in the Clouds | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #8: The Big Four | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #9: The Murder of Roger Ackroyd | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #10: Murder in Mesopotamia | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #11: Hickory Dickory Dock | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #12: Elephants Can Remember | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #13: Hallowe’en Party | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #14: Death on the Nile | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #15: Peril at End House | Ah Sweet Mystery!