Back in April of last year, I received an e-mail from a reader made some lovely comments about the blog – before pointing out a gap in my Golden Age coverage:

“Many/most of my favorites are here, as illustrated by the fine group cartoon that graces the top of the blog. The reason I bring up Charlie Chan is that he’s in the group, but I couldn’t find any posts devoted to the Earl Derr Biggers creation or any of the better films. I’ve always felt the Biggers novels were firmly in the GAD era, even though he insisted on a romance in each one—and Charlie in print is harder to categorize than some of his contemporaries. Anyway, I just wanted to reach out and lobby for some Chan attention.”

The reader, John Swann, is an author himself, with a special interest in Inspector Chan, for John has written two continuation novels about Charlie: Death, I Said and The Tangled String. I wrote back and explained that, while I own all six Chan novels, I had never actually read them. What I have done many times, however, is watch the films; in fact, I own all twenty-three Fox films that are available to watch. (An additional seven titles have been tragically lost, but the Fox collection does contain Eran Trece ((They Were Thirteen)), which is a Spanish-language adaptation of the lost film, Charlie Chan Carries On.)

This “however” has a “however”, er, however: the Charlie Chan films have been problematic, especially in the Bay Area, with our rich legacy of Asian culture. The portrayal of Charlie by white actors has always been a problem, but the larger issue is a fundamental problem with the character of Charlie, both in the books and the films. In his invaluable study Charlie Chan, scholar Yunte Huang speaks about the varied reactions: “To most Caucasian Americans, he is a funny, beloved, albeit somewhat inscrutable – that last adjective already a bit loaded – character who talks wisely and acts even more wisely. But to many Asian Americans, he remains a pernicious example of a racist stereotype, a Yellow Uncle Tom, if you will; the type of Chinaman, passive and unsavory, who conveys himself in broken English.”

Let it be noted that Huang is not here to bury Charlie Chan. His book proposes a more “complicated view: ”To write about Charlie Chan is to write about the undulations of the American cultural experience. Like a blackface minstrel, Charlie Chan carries both the stigma of racial parody and the stimulus of creative imitation . . . Before jumping to any ideologically reductive conclusion, we should pause and think: what would American culture be without minstrelsy, jazz, haiku, Zen, karate, the blues, or anime – without, in other words, the incessant transfusion (and co-opting) of diverse cultural traditions and creative energies?”

The first three Chan films actually did cast Asian performers to play the detective: Japanese actors George Kuwa and Sojin Kamiyama, and Chinese actor E.L. Park. Still, to my understanding, the character of Charlie is a minor one in these films. For the rest of its span from 1931 – 1949, first at 20th Century Fox and later at the Poverty Row Monogram Studios, Chan was played by white actors: Warner Oland in sixteen films, followed by Sidney Toler, who played Chan in eleven films for Fox and eleven more at Monogram. Following Toler’s death, he was succeeded by Roland Winters for six more films.

This was, of course, common practice in Hollywood. John P. Marquand’s Japanese detective Mr. Moto, was dramatized in eight films between 1937-39, with Caucasian actor Peter Lorre playing Moto. Then there was Mr. Wong, another Chinese sleuth, who appeared in a series of short stories written by Hugh Wiley from 1934 to 1940. His filmography might be the closest we get to a success story, for while five of the six films featuring the character starred Boris Karloff, the final film, 1940’s Phantom of Chinatown, starred none other than “former Number One Son, Lee Chan,” Keye Luke, as Mr. Wong. Let it be said, too, that neither Lorre nor Karloff affected any form of pidgin English. Mr. Wong sounded like Boris Karloff, and Mr. Moto sounded . . . Hungarian.

Back to Charlie Chan: after he was retired by Monogram Films, the character was put in storage for twenty-four years. It would have been nice to report that he was revived into a more enlightened Hollywood, but 1973’s The Return of Charlie Chan featured Caucasian actor Ross Martin in the role, and 1981’s Charlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen found no less than Peter Ustinov playing Chan, one year before he returned to the role of Hercule Poirot in Evil Under the Sun. Both films treated the character and the subject matter farcically.

By the 80’s, it was pretty much impossible to find the movies on TV, at least in the Bay Area. You had to look out for Charlie Chan festivals in repertory theatres. I remember taking my first trip to London in 1983 to visit my brother who was at school there. I turned on the TV one day, and a Charlie Chan movie was playing. It had been years since I had seen these, and I would have happily given up sightseeing for a couple of hours to watch the movie, but my host returned with a friend and commandeered the set so that they could watch the snooker championships.

To say that I missed the Charlie Chan films in the intervening years would be an overstatement. I mean, there’s a lot of great stuff to fill our lives, and I didn’t give the absence of these films much thought – until maybe fifteen years ago, when that Fox collection was released on DVD. Bursting with nostalgia, I snapped it up and had myself a marathon. Through grown-up eyes, the mysteries remained charming, sometimes even clever, but the other “stuff” was hard to ignore. The first thing you notice is that the depiction of Black people in the Chan films was even worse than that of Asian characters. Stepin Fetchit in Charlie Chan in Egypt and John H. Allen in Charlie Chan at the Race Track both epitomize what Yunte Huang describes as the “lazy, inarticulate and easily frightened Negro. Once the series moved to Monogram, actor Mantan Moreland, as Charlie’s chauffeur, Birmingham Brown, played a more animated version of the same stereotype for the rest of Charlie Chan’s run.

Charlie is always the smartest person in the room, but he speaks in broken English, often feigns subservience to move forward with his investigations (something Hercule Poirot and probably most other non-English speaking or white male detectives have done in perpetuity) and many of his aphorisms are less about wisdom than about garnering a chuckle: “A big head is no more than a place for a big headache . . .” “Always happens – when conscience tries to speak, telephone out of order . . . ” “Bad alibi like dead fish – cannot stand test of time.” It should be said that Earl Derr Biggers himself resented the use of aphorisms for comedy in the films.

Through six novels and dozens of “B” and “C” movies, Charlie Chan remained part of the history of the Golden Age and a beloved figure in the history of movie mysteries. At least, until everyone’s feelings were taken into consideration. And there’s no denying that the films are entertaining (well, most of them are) and that they contain well-plotted mysteries (well, some of them do) and a wide range of actors performing well (and, sometimes, laughably poorly).I’m not here to argue that there should be a Charlie Chan revival, whether in print or on TV. If there was, the character would have to be seriously recalibrated, and it’s a question whether it’s worth the effort to do so, thought the continuation novels by writers like John Swann may be making a strong argument for such an effort.

But if ever there was a time to put our reservations aside and simply celebrate the character and his legacy, it’s now. This month marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Charlie Chan. On January 24, 1925, the first novel The House Without a Key began serialization in The Saturday Evening Post. Earl Derr Biggers had worked on this novel for years, and it originally had not contained the character of Chan. But an article about legendary Chinese detective Chang Apana of the Honolulu police force inspired Biggers to add Charlie Chan to the plot – and a new detective hero was born.

This month, I have designed a series of activities to celebrate Charlie Chan’s birthday:

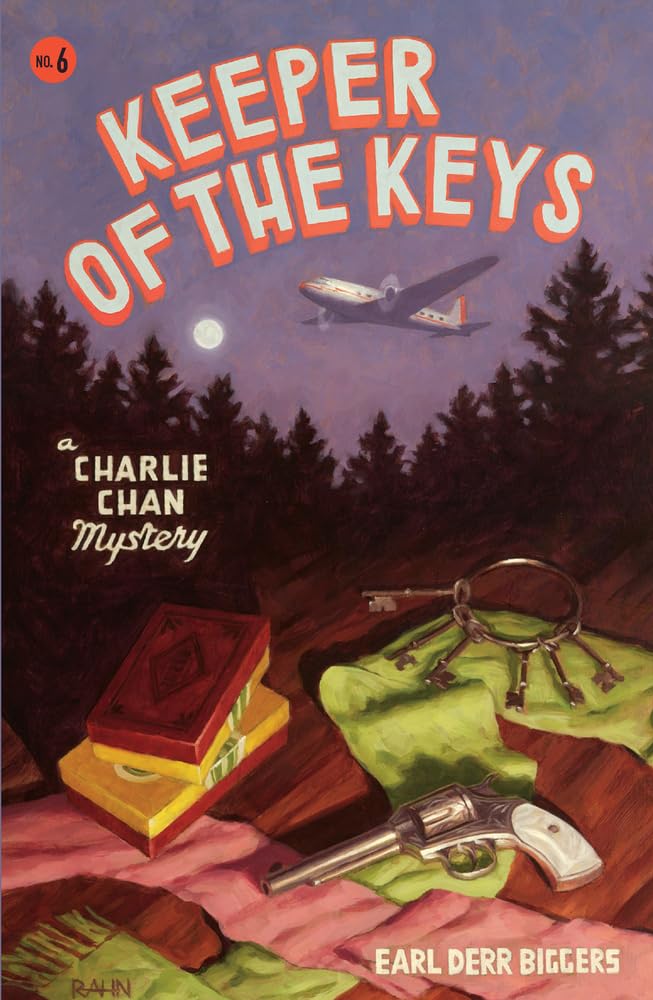

1. I’m going to read my very first Charlie Chan mystery, but rather than start at the beginning, I’m taking John Swann’s advice and reading the final Chan mystery, Keeper of the Keys because . . . well, I’ll let John speak for himself:

“(The) sixth book represents the most fully realized character of Chan; i.e., brilliant detective, student of human nature, philosopher, and Chinese-American pondering his betwixt-and-between place as someone who values the country of his birth and his heritage, but is sneered at as “not truly Chinese” by some . . . and viewed as hopelessly old-fashioned by his too-Americanized offspring. By the time Biggers finished the sixth book, he had come a long way from the more roughly sketched Chan of the first book, The House Without a Key. On the whole, the Chan of the books is quite a bit more complex than even the best Hollywood rendering.”

I plan to post this review on Charlie’s actual “birthday”: January 24. And would you believe it? I convinced my Book Club to make Keeper of the Keys its January read, so expect multiple reviews by the end of the month!

2. Before January is over, I will post a review of a mystery featuring another Chinese detective. My friend Kate Jackson over at Cross-Examining Crime has been championing the work of Juanita Sheridan who, between 1949 and 1953, produced four whodunnits featuring detective Lily Wu. As luck would have it, I found four pristine used copies of these books at my local used bookstore for a song and snapped them up. It’ll be interesting to read one of these and compare Lily to Charlie Chan.

3. On February 8, I will be meeting with my buddies Sergio Angelini and Nick Cardillo to draft the TOP THIRTEEN FOX CHARLIE CHAN FILMS. We have watched all twenty-three movies and made our notes. On February 10th, I will post the results of that draft. And then, on the 12th, I will share with you my complete ranking of all 23 films, along with my notes.

If you would like to join in the celebration, pick up a copy of Keeper of the Keys and read along with me. And if you would like to dive into the Charlie Chan film archive, I have great news: all of these movies are in the public domain and can be found in (mostly) pristine prints on YouTube. Feel free to watch along and let us know if you agree with our rankings. Finally, if you would like to express any feelings about the character, his depiction in the books, or his representation in the films, you are welcome. I only ask that any opinions be presented respectfully.

Here is a list of the Fox films, in case you want to watch them before our draft comes out. You can print the list out and put together your own rankings to compare with ours. (Remember: Sergio, Nick and I will be drafting the top thirteen out of twenty-three films.)

| RANK | TITLE | YEAR | CHAN | GUEST STARS |

| The Black Camel | 1931 | Oland | Bela Lugosi, Robert Young | |

| Charlie Chan in London | 1934 | Oland | Ray Milland | |

| Charlie Chan in Paris | 1935 | Oland | Keye Luke (1st), Mary Brian | |

| Charlie Chan in Egypt | 1935 | Oland | Rita Hayworth, Stepin Fetchit | |

| Charlie Chan in Shanghai | 1935 | Oland | Keye Luke, Jon Hall | |

| Charlie Chan’s Secret | 1936 | Oland | Rosina Lawrence | |

| Charlie Chan at the Circus | 1936 | Oland | Keye Luke, The Brasnos | |

| Charlie Chan at the Race Track | 1936 | Oland | Keye Luke, Helen Wood | |

| Charlie Chan at the Opera | 1936 | Oland | Boris Karloff, William Demarest | |

| Charlie Chan at the Olympics | 1937 | Oland | Keye Luke, Katherine De Mille | |

| Charlie Chan on Broadway | 1937 | Oland | Keye Luke, Harold Huber | |

| Charlie Chan at Monte Carlo | 1937 | Oland | Keye Luke, Sidney Blackmer | |

| Charlie Chan in Honolulu | 1939 | Toler | Victor Sen Yung, Phyllis Brooks, Claire Dodd | |

| Charlie Chan in Reno | 1939 | Toler | Sen Yung, Phyllis Brooks, Ricardo Cortez | |

| Charlie Chan at Treasure Island | 1939 | Toler | Sen Yung, Cesar Romero | |

| City in Darkness | 1939 | Toler | Lynn Bari, Leo G. Carroll | |

| Charlie Chan in Panama | 1940 | Toler | Sen Yung, Lionel Atwill, Mary Nash | |

| Charlie Chan’s Murder Cruise | 1940 | Toler | Sen Yung, Lionel Atwill, Leo G. Carroll | |

| Charlie Chan at the Wax Museum | 1940 | Toler | Sen Yung, C. Harry Gordon | |

| Murder Over New York | 1940 | Toler | Sen Yung, Ricardo Cortez | |

| Dead Men Tell | 1941 | Toler | Sen Yung, Sheila Ryan | |

| Charlie Chan in Rio | 1941 | Toler | Sen Yung, Harold Huber | |

| Castle in the Desert | 1942 | Toler | Sen Yung, Henry Daniell |

I’ll be back on January 24 with my review of Keeper of the Keys.

P.S. Many thanks to Sergio “The Human Film Encyclopedia” Angelini for necessary corrections to my humble efforts. As Charlie Chan says: “Always pleasant journey which ends among old friends.”

Revisiting the Chan films was a great, nostalgic pleasure and I cannot wait to discuss them all with you and Sergio! (I have also made my official ranking of all 23 if it can be of any use to you…!)

I was also hoping to read The Black Camel in anticipation of our draft. Years ago, when I was something of a Chan-obsessive, I read the first three novels but stopped. I just read Charlie Chan Carries On which made for a fun comparison with the film adaptation(s). We’ll see if Can squeeze in Keeper of the Keys too!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Eventually, for Murder, She Watched, I’ll be watching a selection of Charlie Chan films because he is a famous detective. I look forward to your discussion!

In the meantime, did you know about Charlie Chan at the Movies: History, Filmography, and Criticism by Ken Hanke (2004)? It’s from McFarland & Company, publisher of all things scholarly. It’s expensive so we got our copy via the interlibrary loan.

It’s an exhaustive review of EACH Charlie Chan film, rating them, with cast lists and so forth. If you’re looking at Charlie Chan films, this was a stunningly useful resource.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love that book; I just can’t afford to buy it!

LikeLike

While it’s impossible for me to view the Chan films from the perspective of an Asian American, I think it’s important to note that there’s a wide range, in both quality and sensitivity, to the filmography of the character. The films are not of one piece. I think there’s a big difference between Oland’s Chan of CC IN Paris, gently putting racist Erik Rhodes in his place, and some of the less reflective final Toler or Winters portrayals. And while my hero Peter Ustinov and his Chan film are unquestionably farcical and highly embarrassing (somewhat ironic as Ustinov is sometimes criticized as being an apologist for the Chinese), I really don’t see how Ross Martin’s portrayal or teleplay can be seem as anything but (at least relatively) respectful. One may not like the film or the portrayal, but I really do feel it’s as undeniably respectful of the character as any of the portrayals we’ve had.

Incidentally, I really love Hanke’s book. He was a very erudite and witty fellow, and is much missed.

LikeLike

While it’s impossible for me to view the Chan films from the perspective of an Asian American, I think it’s important to note that there’s a wide range, in both quality and sensitivity, to the filmography of the character. The films are not of one piece. I think there’s a big difference between Oland’s Chan of CC IN Paris, gently putting racist Erik Rhodes in his place, and some of the less reflective final Toler or Winters portrayals. And while my hero Peter Ustinov and his Chan film are unquestionably farcical and highly embarrassing (somewhat ironic as Ustinov is sometimes criticized as being an apologist for the Chinese), I really don’t see how Ross Martin’s portrayal or teleplay can be seem as anything but (at least relatively) respectful. One may not like the film or the portrayal, but I really do feel it’s as undeniably respectful of the character as any of the portrayals we’ve had.

Incidentally, I really love Hanke’s book. He was a very erudite and witty fellow, and is much missed.

LikeLike

From my very rough recall of a few of the films, I daresay it would be quite the headache to completely transform the character of Charly Chan. I suspect the easiest path would be to keep the time-frame, portray the subtle and not-so-subtle daily racism and show the well-known Charly Chan demeanour and way of speaking to be nothing but a persona. We might get to see him dream up things to say that will impress his clients, we might see his wife complain to him she cannot put more tasteful decorations in the room where he sees clients – or the other way around. The actor would certainly have a blast, and it should make it easier to adapt the cases without too many changes. What do you think?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Based on my very limited reading, there’s a lot in the books that could be incorporated into a modern-day rendition of Charlie Chan. He describes his choice to “Americanize” himself in order to fit into society, the cost of that decision. This element could be easily explored in a period drama. The question is: what sort of cases would a reimagined Charlie take on today? Do they need to be darker, less Golden Age in style? I honestly don’t know, but I doubt anyone taking on the character could, or would want to, duplicate the old films.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with everything you wrote about the actors playing Chan. It puzzles me why his children and other family members were always cast with Asian actors, but never the man himself.

And, just in case you haven’t enough to watch, there is this:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0068037

LikeLiked by 1 person