It’s easy to argue that The Big Four represents the artistic nadir of Agatha Christie’s career. It barely makes a mention in the biographies: Laura Thompson calls it “one of the worst pieces of writing she ever published but . . . it sold well.” Janet Morgan dismisses it as “a stopgap.” Gillian Gill takes a more interesting tack, using the book to prove that Christie’s antisemitism was of the “stupidly unthinking rather than the deliberately vicious kind” because in The Big Four her conspirators aren’t Jewish:

“ . . . she conspicuously refuses to buy into the obsession with a secret world Jewish-Communist-Freemason conspiracy that still haunts so many otherwise sane Europeans of her generation and the next.”

The author herself called The Big Four “that rotten book.” Robert Barnard agrees that it’’s “dreadful,” but he advises readers to be charitable. For after the crisis-laden 1926 that she had experienced, losing her mother and her husband, Agatha needed money. Her brother-in-law, Campbell Christie, suggested that she take the twelve stories she had published during the first months of 1924 under the title The Man Who Was No. 4 and cobble them together into a novel. He even offered to write the sections that would link the stories together into a whole.

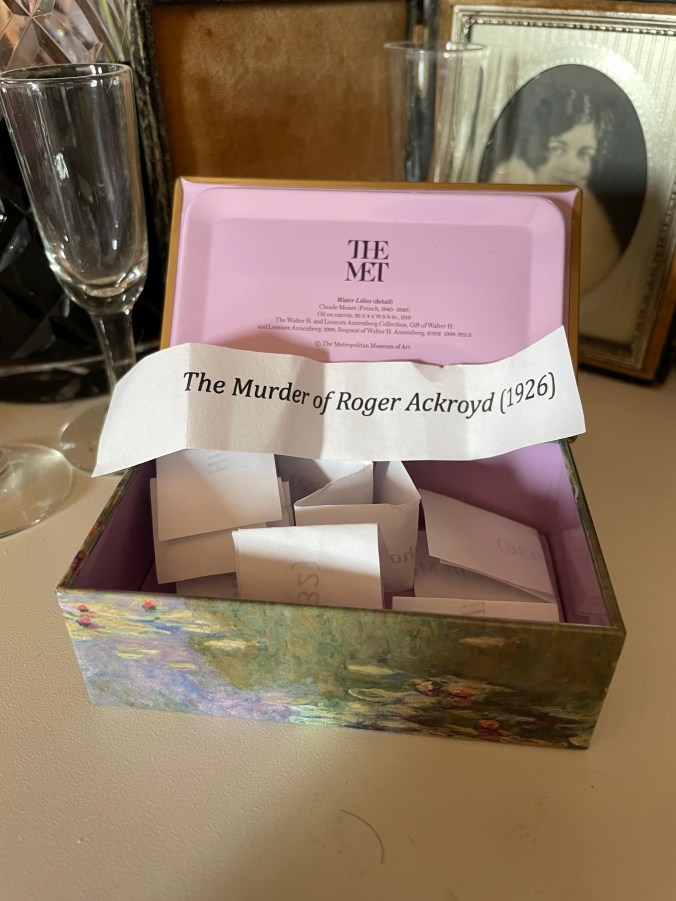

Christie accepted the offer and turned in the finished product to her publisher, Bodley Head – who rejected it. As Gill points out, Campbell Christie would remain a devoted friend to Agatha despite the divorce, “but unfortunately, (he was) no more in tune with Agatha’s talents and themes as a writer than Archie had been.” Christie left Bodley Head and submitted another novel The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, to her new publisher William Collins and Sons. Collins then published in succession The Big Four in 1927 and The Mystery of the Blue Train in 1928, Agatha’s two least favorite novels, before settling in to the great run that continued for nearly fifty years.

The nine novels written during the 1920’s easily divide into the whodunnits, featuring Hercule Poirot, and the thrillers – with one exception:

| HERCULE POIROT WHODUNNITS | THRILLERS |

| The Mysterious Affair at Styles | The Secret Adversary |

| The Murder on the Links | The Man in the Brown Suit |

| The Murder of Roger Ackroyd | The Secret of Chimneys |

| The Mystery of the Blue Train | The Seven Dials Mystery |

Where do we place The Big Four, which straddles both lists and is arguably the worst of each? Personally, I would slot it just above Chimneys at the bottom of the thrillers list; it has no place on the other side! And yet, how are we to account for the novel’s generally good reviews and popularity amongst readers? Christie may have lucked out by submitting the brilliant Ackroyd ahead of this one, allowing her to ride the good feelings of her audience. Then again, conspiracy theories were all the rage between the wars, and Christie was tapping into the zeitgeist.

The Observer summed up the novel’s strengths and weaknesses in its review of February 13, 1927:

“When one opens a book and finds the name Li Chang Yen and is taken to subterranean chambers in the East End ‘hung with rich Oriental silks’, one fears the worst. Not that Mrs. Christie gives us the worst; she is far too adroit and accomplished a hand for that. But the short, interpolated mysteries within the mystery are really much more interesting than the machinations of the ‘Big Four’ supermen.”

I’ll admit that I had fun the first time I read this – but I was fifteen, and the book was exciting in much the same way as the old Batman TV show – if Batman were 5’4” and sported a luxurious mustache. In re-reading it for maybe the fourth time, I felt more distance from the enjoyment I had as a kid. It feels like parody . . . which may explain why Agatha found it so easy to spoof a mere few months after the stories came out! (Check out the Poirot-centered story in Partners in Crime, a story collection that handles the concept of a world conspiracy with more creativity and humor!)

The big challenge for me here is how to rank this one within the categories I have created. In terms of character, plot, Poirot (!), I fear I’m in the same boat that Catherine Brobeck and Kemper Donovan must have found themselves when they tackled the book on All About Agatha! But then it managed to land exactly where I would have put it myself on their list.

Oh, well . . . on with our own ratings game!

* * * * *

The Hook

“I should be (in London) some months – time enough to look up old friends, and one old friend in particular. A little man with an egg-shaped head and green eyes – Hercule Poirot! I proposed to take him completely by surprise.”

The best laid plans of Captain Arthur Hastings oft go astray, but the joke here is that the Great Man himself was planning the same thing! Their joyful reunion is interrupted by an intruder, who collapses on the ground and cannot be revived – until Hastings jokingly refers to Poirot’s latest idee fixe, something called “The Big Four.” Whereupon the stranger revives and, in the manner of Mr. Memory from Hitchcock’s adaptation of The 39 Steps (which won’t grace screens until 1935), he sets up the hokum to follow:

“Li Chang Yen may be regarded as representing the brains of the Big Four. He is the controlling and motive force. I have designated him, therefore, as Number One. Number Two is seldom mentioned by name. He is represented by an S with two lines through it – the sign for a dollar; also by two stripes and a star. It may be conjectured, therefore, that he is an American subject, and that he represents the power of wealth. There seems no doubt that Number Three is a woman, and her nationality French. It is possible that she may be one of the sirens of the demimonde, but nothing is known definitely. Number four –. . . the destroyer!”

One of the main problems with The Big Four can be summed up by looking at the part of this speech dealing with Number Two (I am so tempted to make a joke!) and the questions it raises? Why does Number Two need two symbolic representations? Doesn’t the dollar sign alone give us all the information we need? And why does it take so long for Poirot to associate this symbol with Abe Ryland, the American millionaire who, out of the blue, has employed Poirot to hurry to the Argentine on a matter of utmost vagueness importance? In short, in the midst of all this amazing amazement, there is some level of stupidity brewing. And it won’t be helped as we move along, and the episodic nature of this material’s original presentation rears its head in constant repetitions of the above information.

But if you look at the whole thing as if it were a movie serial, the opening chapter is exciting: Poirot and Hastings leave the man behind in order for the detective to make his ship for South America; then they jump off the train as Poirot realizes he’s been had; then they return to the flat to discover their informant has been horribly murdered; then the man’s body is spirited away by none other than Number Four, whose mastery of disguise will be hammered into our brains innumerable times.

I would add a point for sentimental value, seeing how this is a moment of reunion for two dear friends after Hastings got married and moved out of the country. But since both The Murder on the Links and all the stories later gathered into Poirot Investigates/Poirot’s Early Cases had appeared throughout 1923, I can’t imagine that the audiences of the day felt they were witnessing a striking event – certainly not the way we all felt when we first read Curtain.

Score: 5/10

The Closed Circle: Who, What, When, Where, Why?

Who?

There are dozens and dozens of characters moving through The Big Four, yet, aside from Poirot, Hastings, Japp, and the welcome return of the Countess Vera Russakoff, there isn’t a woman or man in here that I feel better for having known. Christie leans into some frankly awful cultural stereotypes and literary clichés. Lots of people die, but we never know them well enough to care about them. The same goes for those who commit the crimes – most of whom turn out to be the same man in disguise.

Let’s make do, then, with a quick glance at the Big Four themselves:

Number One, Li Chang Yen, is the unseen brains behind the outfit, but it is an Oriental brain and therefore insidious and dangerous. Li is a weary retread of Dr. Fu Manchu with a dash of the yet-to-come Hitler. His goal is nothing less than “the disintegration of civilization” followed by the establishment of total anarchy ruled by Li and his three buddies. Li is given credit for most of the civil unrest occurring around the world, including the October Revolution. World leaders, like Lenin and Trotsky, are said to be his puppets. He resides in a palace in Peking, where he oversees horrifying experiments against Chinese coolies and the invention of weapons of mass destruction. He is your standard Other, a walking advertisement for the dangers of Orientalism, a world conqueror whom we never meet and who, after the group fails, makes an ignominious end of himself.

Number Two, Abe Ryland, is a bore – one of Christie’s stock American millionaires who has dedicated his dollars to controlling the world’s economy. We actually don’t see much of him, as his biggest scenes are cast with an imposter. The best that can be said of him is that he recognizes Hercule Poirot’s abilities early on enough to attempt to neutralize the threat.

Number Three, Madame Olivier, is the world’s greatest scientist, “more famous than Curie,” whose face has been scarred by a laboratory accident. (See what happens to women when they lose their beauty? They become super-villains.) I have a feeling that her unmasking on the page is supposed to be a surprise, since everyone initially was thinking of a French Mata Hari figure. Even at fifteen, I wasn’t surprised.

Number Four is a master of disguise known as “The Destroyer.” He is really Claude Durrell, an English actor whose career never took off, leading him to turn to his fallback career – assassin and spy. He takes on half a dozen or so roles in the novel, without much attention paid to how he could play two or more of these at the same time. Claude’s presence frankly becomes a crutch for Christie: if someone is named as a murderer, Poirot assumes that he must be Number Four. It grows dull pretty quickly. Eventually, we learn a bit about his past, but by then it’s too late to care. We also learn that Claude has what must be the silliest identifying habit in crime fiction, that of rolling bits of bread around on his plate at mealtimes.

What?

What, indeed?

In brief, four extraordinary people want to take over the world. The Big Four seem to be responsible for everything that goes wrong in every country, but oddly they seem to focus their main actions on small events in the greater London area. And only one person in all the world stands in their way of success –Hercule Poirot.

None of this makes sense. Why these four? Why would representatives from China, America, England and France team up together? Why leave out Spain or South America or that perpetual antagonist in world conflict, Germany? It’s all comic book stuff – a Legion of Super Villains, power for power’s sake, mass-destruction because that’s what evil people do!

And why Poirot? I imagine Christie had fun transforming her master of ratiocination into an action hero, but the mantle rests uneasily on his plump shoulders. Moments like when Poirot, on the verge of death, asks for a cigarette and then informs his captors that he is now smoking a blow pipe filled with curare are utterly ludicrous. And if Poirot is the world’s only hope, why isn’t he smarter about it?

If you can relax and stop trying to make sense of any of it, the book flows with a modicum of enjoyment as Poirot and Hastings face off against Numbers Two and Three and track down the elusive Number Four. And since the book is episodic, one can pick and highlight the best episodes. No surprise that these are the chapters that most resemble a traditional Poirot mystery tale, with the most famous being Chapter Eleven, “A Chess Problem.” Taken alone, the story is great fun; how unfortunate that once the killer is revealed, it turns out to be just another disguise for . . . you-know-who!

I also have a special fondness for the section comprised of Chapters Twelve and Thirteen, where Hastings is fooled into believing that his beloved wife Cinderella has been kidnapped. (Beloved? Why has he spent the last six months away from her battling global evil without making sure she’s safe?) Hastings is forced to lure Poirot into a trap, or else Cinderella will die “by the Seventy Lingering Deaths.” Of course, Poirot arrives armed with tear gas and a respirator and saves the day. What makes me smile is the moment at the end when we realize that Poirot really loves this dumb cluck of a friend of his:

“I turned my head aside. Poirot put his hand on my shoulder. There was something in his voice that I had never heard there before. ‘You like not that I should embrace you or display the emotion, I know well. I will be very British. I will say nothing – but nothing at all. Only this – that in this last adventure of ours, the honors are all with you, and happy is the man who has such a friend as I have!’”

I always get a little tired of how dense Hastings can be, but without a doubt his bravery and affection for Poirot hold clear throughout. (But, seriously – why leave his wife for almost a year?)

When and where?

The book takes place here, there, and everywhere, but we never stop long enough to take in any settings. Over the course of nearly a year, Poirot travels a lot, falls out of trains twice, winds up in many secret lairs, and fakes both his own death and the coming to life of his twin brother Achille. Evidently the timing of the book in the 1920’s is relevant, as conspiracy theories abounded between the wars. Honestly, if you’re going to read The Big Four, now is also a good time to pick up the book. Ours is a conspiracy-laden society, and the novel could sadly be read as a screed against American oligarchs, non-white Others, and working women. Oh, and actors! We must always be wary of actors!!!

Score: 5/10

The Solution and How He Gets There (10 points)

This is the least fair category to slot into a review of The Big Four because there is no overarching solution. Poirot is one of the few to have picked up on the existence of an international conspiracy but others who have already done the heavy lifting fill him in on all the details. That leaves room for actual “detection” on two fronts: the unmasking of Number Four in his various guises, and the solutions to smaller but connected cases that Poirot takes. As I mentioned, the Number Four business repeats endlessly without a modicum of cleverness – except perhaps in “The Importance of a Leg of Mutton,” where Poirot has clearly been reading his Chesterton and identifies an overused trick, and “A Chess Problem,” as described above.

In fact, Poirot’s little grey cells here might need recharging. He couldn’t be more certain about the identity of Number Two if the man had sent him his card, and yet he totally muffs up the man’s capture. And he makes a mess of things with Number Three – although he does manage to have those curare cigarettes handy just in case. Once he and Hastings escape from Number Three’s trap, Poirot at least has the decency to berate himself:

“I deserve all that that woman said to me. I am a triple imbecile, a miserable animal, thirty-six times an idiot. I was proud of myself for not falling into their trap. And it was not even meant as a trap – except exactly in the way in which I fell into it. They knew I would see through it – they counted on my seeing through it.”

Score: 4/10

The Poirot Factor

“No, my friend Hastings, . . . Hercule Poirot’s methods are his own. Order and method, and ‘the little grey cells.’ Sitting at ease in our own armchairs we see the things that these others overlook, and we do not jump to the conclusion like the worthy Japp.’”

As I’ve stated above, Poirot behaves out of character far too often in order to fit him, however uncomfortably, into the role of action hero. “Order and method” have little to do with his entanglement with the Big Four. In a way, his combination of Gallic elegance and sudden physical action makes me think of a Belgian version of John Steed from The Avengers – until I’m struck with the image of Hugh Fraser’s Captain Hastings – in Mrs. Peel drag!!! I find it hard to believe that the man who was horrified at the thought that he might have drunk Sir Charles Cartwright’s poisoned cocktail would risk his own life so many times, but what’s more horrifying is how often he risks Hastings’ life.

And yet Poirot is still Poirot . . . at least much of the time. His reunion with Hastings at the beginning is enjoyable, and the sacrifice of his moustache to save the world is a humorous sort of miracle. Collins clearly depended on the public’s love of the character to boost sales of this novel, and you can pretty much understand why they thought this way. And while none of us may swallow the suggestion that Poirot has been killed, the whole final sequence deals with that in an enjoyable way.

Score: 6/10

The Wow Factor

Any “wow” factor here is ironic, but the book does stand out amongst its brethren as the only thriller where Poirot is the star. We’ll also find thriller elements in the much better Cat Among the Pigeons and the not-so-good The Clocks, – but notice how little Poirot appears in either of those books!

My biggest “wow” is reserved for a different Big Four altogether – the one adapted by Mark Gatiss for David Suchet in the final season of Poirot. The episode is most notable for bringing Hugh Fraser’ Hastings and Pauline Moran’s Miss Lemon back for their final hurrah as a team. What Gatiss has managed to do is take the best parts from the novel – the three murder cases – and thread them together with rumors of the secret organization without requiring us to watch any of the outlandish and outdated scenes from the book where Poirot and Hastings face down the Big Four. Instead, Gatiss conceives of a wholly different explanation that is no less outlandish but rather creative – and infinitely more manageable.

I’ll bet that this adaptation divides Christie fans into those who see a definite improvement from the novel and those who would just as soon have seen no adaptation at all. I can’t imagine a more faithful rendering could have been produced without either offending or making people laugh. So . . . a gutsy move by Mr. Gatiss, inspired by a book that is nearly unadaptable!

Score: 3/10

FINAL SCORE FOR THE BIG FOUR: 23/50

THE POIROT PROJECT RANKINGS SO FAR . . .

- The A.B.C. Murders (46 points)

- Three-Act Tragedy (42 points)

- Cards on the Table (36 points)

- Death in the Clouds (35 points)

- One, Two, Buckle My Shoe (34 points)

- Dead Man’s Folly (28 points)

- The Mystery of the Blue Train (26 points)

- The Big Four (23 points)

Next time . . .

Frankly, I’m shocked that this blog has not yet covered this novel in detail. Next month, we’ll correct that oversight!

This is easily my least favourite except for her very, very late novels. And even then, I may actually prefer the Elephants, I’m not sure. I don’t even enjoy this in a just having fun way, I just dislike reading it. But you have been fair to it. Much fairer than I would probably have been.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve read this several times over the years. Each time, it becomes harder to consider the context in which it was written. This time out, I decided to listen to it. Hearing Hugh Fraser read the scene where Hastings is kidnapped by a minion of Li’s – alternating the insidious Asian accent with Hastings shouting, “You fiend!” – does not endear one to this book! But I did have a few uncomfortable chuckles in the car.

LikeLike

It has been years since I read The Big Four and I am overly keen on revisiting it. I understand what Christie was going for here, but I never found her in Edgar Wallace mode all that convincing and the inclusion of Poirot makes it stand out uncomfortably alongside the other novels in the Poirot series. I will readily admit though that I find the Gatiss adaptation rather delightful. It’s still incredibly silly, but it is an improvement on the source material and it is fun to see the series family – albeit briefly – all together again.

LikeLike

Really enjoyed your post but … I’m still not going to re-read the damn thing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You were a blogger, so you know this: we reread these things so you don’t have to!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ridiculous but not as dreadful as Passenger to Frankfurt. Sometimes, it’s hard to believe that the person who wrote After the Funeral and Five Little Pigs also wrote these.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Passenger to Frankfurt SEEMED like a good idea – to an eighty-year-old woman who had always been fascinated with Wagnerian international conspiracies. Big Four might have slipped by as a magazine serial about a similar conspiracy, a Fu Manchu knockoff – but the travails of life led Christie to make a decision that some fans enjoy and others still question.

LikeLike

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #9: The Murder of Roger Ackroyd | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #10: Murder in Mesopotamia | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #11: Hickory Dickory Dock | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #12: Elephants Can Remember | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #13: Hallowe’en Party | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #14: Death on the Nile | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #15: Peril at End House | Ah Sweet Mystery!