“Your travel life has the essence of a dream . . . you are yourself, but a different self.” (Agatha Christie)

Full disclosure: I’ve tried writing this article five times, and it becomes increasingly difficult to stick to the subject. My basic issue around Murder in Mesopotamia is that, despite a few interesting features, what fascinates me more about the book is everything around it – all the stuff that reveals information about Agatha Christie and her life. Thus, I ask you to bear with me here: I’ll get to the rankings, but I’d like to talk first about a few other things . . .

Like . . . The Murder of Roger Ackroyd was published at the emotional nadir of Agatha’s life, and yet she managed to shake off her mother’s death, her disintegrating marriage, and the short stories she had recently published that would form The Big Four, perhaps the low-point in Hercule Poirot’s career, to produce the best book of the 20’s and a sure classic in the canon. And then, in the 1930’s, when Christie was at the top of both her professional and personal life, when she was on a roll as far as Poirot was concerned, she wrote Murder in Mesopotamia – not a bad book by any means, but arguably the least and the dullest of her Poirot travel novels and one of the lowest ranked of her 30’s output. (Just for fun, I looked it up on the All About Agatha rankings list: it placed 16th out of seventeen 30’s novels, with Dumb Witness placing just one spot lower.)

The book contains several interesting features:

- Despite her rich characterization of women and girls, Christie almost never allowed a woman to narrate the stories. Off the top of my head, I can think of three: Anne Beddingfield in The Man in the Brown Suit, Miss Marple in “Miss Marple Tells a Story,” and, of course, Mesopotamia’s Amy Leatheran. My favorite of the three, of course, is Miss Marple, but Amy is a good narrator: observant like any capable nurse, and charmingly self-deprecating.

- The impossible crime mystery is a hugely popular subset of the genre, but it is not one that Christie stuck her toe in very often, as I’ve written about before. Perhaps the very best example is one that some folks don’t even include because the impossibility is almost snuck in at the end, and that’s And Then There Were None. I would argue that this brief moment achieves everything an impossible crime mystery should and more – but it leads us in a direction beyond the scope of our present discussion. The two major Hercule Poirot’s Christmas and Mesopotamia. Many a locked-room mystery fan finds both of these examples to be problematic, but they achieve the same effect that many a Carr, Rawson, Halter and writers of their ilk set out to accomplish.

- The gold standard of Agatha’s travel mysteries, Death on the Nile and Murder on the Orient Express, may depend at least in part for atmosphere on Christie’s own journeys; the same goes for the perfectly competent Appointment with Death, A Caribbean Mystery and most of the thrillers. But Murder in Mesoptamia is teeming with Christie lore: the day-to-day workings at an archaeological dig become, for the first and only time, a closed circle setting. And the victim, the magnificent Louise Leidner, is based on Christie’s good friend Katherine Woolley, a woman evidently so self-centered that when she read the book, she did not recognize herself in it!

For Christie, there were few things more glorious than travel. I wish her Autobiography were as stuffed with thoughts about her own work as it is with delicious details about her voyages around the world. We’ve seen how her trip around the world with Archie led to Major Belcher, the obnoxious man who inspired the best character in The Man in the Brown Suit. We’ve witnessed how she tried unsuccessfully to bury herself in her work after her mother died and Archie left, but only by sequestering herself in the Canary Islands was she able to churn out The Mystery of the Blue Train. We saw how a restorative trip aboard the Orient Express inspired one of Agatha’s most ingenious books.

When she returned to the Middle East to recover from her divorce, Agatha was unprepared for how Anglo-philed it had become. She sought escape from the old biddies and stuffy tea parties she found in Baghdad and would journey outside the city whenever she could. I was struck by some of her findings, not so much in the details of what she saw but in how her interpretation of them illuminates the way we see her work:“I learned soon enough that nothing in the Near East is what it appears to be. One’s rules of life and conduct, observation and behavior, have all to be reversed, and re-learns.” And isn’t that true of Christie’s plots and characters? Nothing and no one is exactly what they appear to be.

Lucy Worsley offers insight into Christie’s romantic notions of the Middle East, and I think her description here is also apt in describing the author as both a romantic and a journeyman, an eager observer of the world around her and one who puts those observations to work for her:

“. . . she would never really be an archaeologist, in the sense that she was never paid for her work. Her retrospective account of her trip on the Orient Express may reflect less her real experience in 1928 than the genre of archaeological writing which often begins with the ‘epic journey’. The archaeologist narrating the story becomes the protagonist of an odyssey. Indeed, for popular archaeology, the fieldwork itself doesn’t really matter.”

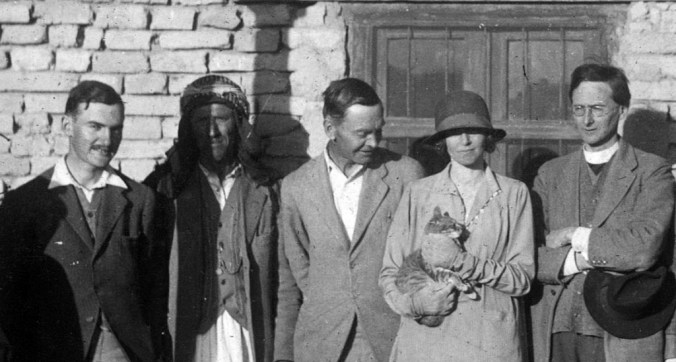

On that restorative “epic journey” in 1928-29, Agatha wanted to visit the archaeological dig at Ur. Her request was met by a stroke of luck: Katherine Woolley, the wife of the dig leader, Leonard Woolley, had just read The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and loved it. An invitation was sent, and Agatha found herself a welcome guest behind the closed doors of the expedition house. Max was nowhere in sight. He had taken ill and begged off this year’s expedition; happily, Agatha would return the following year and meet her future second husband.

Agatha’s description of that first visit is delightful. She meets Leonard, all kindly and helpful, just like Dr. Eric Leidner (if Leidner wasn’t an insane murderer.) She meets Father Burrows, a Jesuit priest and the resident epigraphist, who actually gave her an idea for a mystery story that she would turn into her own a quarter century later; he is similar to Father Lavigny (if the latter hadn’t been a fraud and a thief.) But most important of all, Agatha met Katherine, whom she would count a great friend in the years to come and whom she considered “an extraordinary character:

“People have been divided always between disliking her with a fierce and vengeful hatred, and being entranced by her – possibly because she switched from one mood to another so easily that you never knew where you were with her. People would declare that she was impossible, that they would have no more to do with her, that it was insupportable the way she treated you; and then, suddenly, once again, they would be fascinated.”

Agatha speaks almost entirely positively about Katherine Woolley. Christie’s biographers are not so reticient, pointing out dtails of her seductive, neurotic personality and the oddness of her marriage to Leonard. I love the salacious detail about the Woolleys having an essentially sexless marriage, apart from Katherine allowing Leonard to watch her bathe at night. No matter what the truth about her, Katherine inspired the best character in Murder in Mesopotamia, and one of the most intriguing victims in the canon.

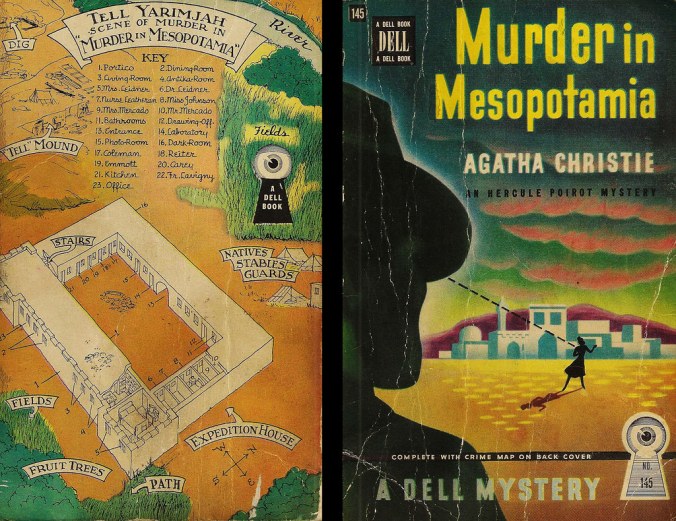

In the end, Tell Yarimjah, a fictionalized depiction of Ur, provides an interesting setting, and it’s employees make up a circle of suspects that, while perhaps less interesting, are at least well motivated to kill. These folks love, hate, feel jealousy toward, or fear Louise. And one of them conceives of a murder plot that will have the investigators and readers scratching their heads over the “howdunnit” of it all.

And yet . . . there is an elephant in this dig, and it’s a big one. Fans of Christie are painfully aware of what I’m talking about, and it divides them over how much it affects their enjoyment of the overall book. We’ll get into it below, but I’ll spoil this much for you right away: it bothers me a lot

* * * * *

The Hook

“There have been the wildest and most ridiculous rumors suggesting that important evidence was suppressed and other nonsense of that kind. Those misconceptions have appeared more especially in the American press. For obvious reasons, it was desirable that the account should not come from the pen of one of the expedition staff, who might reasonably be supposed to be prejudiced. I therefore suggested to Miss Amy Leatheran that she should undertake the task.”

I’m a little puzzled at the idea that the public would be interested in reading about a case that took place four years earlier, but I’m more curious as to what these “rumors and misconceptions” might be. Anyway . . . Amy Leatheran, the only “outsider” in the case, is chosen to take up the story, and she begins by asserting that she is not up to the task: “I don’t pretend to be an author or to know anything about writing. I’m doing this simply because Dr. Reilly asked me to, and somehow when Dr. Reilly asks you to do a thing you don’t like to refuse.” Again, the mischievous imp in me asks why someone so insecure about her talents should be given the helm as authoress, since the purpose must be to sell books!

“Treat it as case notes,” Dr. Reilly tells her, and one almost wonders if there were such notes taken from which Amy could pull; how else to explain her extraordinary memory for conversations and details four years after the fact? And of course, Amy can’t submit any such thing as “case notes!” A book, even a “non-fiction” document as this book purports to be, must contain sufficient drama to balance the plenitude of information that the writer is recounting in order to grab the reader’s attention. What Amy gives us may be the most traditional opening section in the canon: she is hired to do a job, she is given information about the people she will encounter, and then she takes up her post. Arguably, the “hook” stops here!

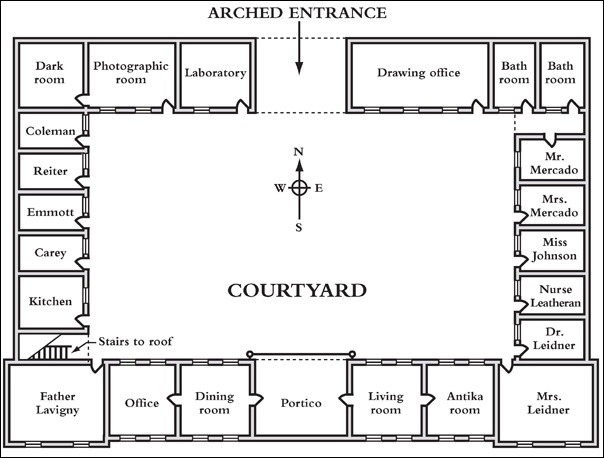

Amy actually describes the occupants of Tell Yarimjah twice. In Chapter Three, “Gossip,” she has the good fortune to receive detailed information about each person there from a friend of her ex-employers. This squadron leader is extraordinarily sensitive in his detailed portraits, both of the people and the place: “There was a queer atmosphere of tension. I can explain best what I mean by saying that they all passed the butter to each other too politely.”

After this, Amy makes her journey and conveys her own first impressions of each person. She also senses the tension and is able to describe it and assume that her patient, Mrs. Leidner, is the source. I don’t see how we can go further. Amy leaves behind the familiar, filled with excitement and unease over the job to come. Christie has poured on this unease, chiefly (and rather cleverly) through the impressions everyone has of Louise Leidner, a potential troublemaker, and her husband, a man so kind and gentle and quietly authoritative that if he wants his wife to have a nurse protector, he too must sense something wrong at Tell Yarimjah. It’s a perfectly legitimate opening – not terribly exciting but nicely character-driven. But are we propelled to move forward by Amy’s narration or by the faith that we have gained, from previous reads, in Mrs. Christie’s abilities?

As Amy herself says, “Well, I must wait and see.”

Score: 6/10

The Closed Circle: Who, What, When, Where, Why?

Who?

“Yes, individually, they are all pleasant people. But somehow or other, I may have been fanciful, but the last time I went to see them I got a queer impression of something being wrong. I don’t know what it was exactly. Nobody seemed quite natural. It was a queer atmosphere of tension. I can explain best what I mean by saying that they all passed the butter to each other too politely.”

Midway through the 1930’s, Christie began making the switch from reliance on stock character tropes to creating fully-fleshed people. Think of the sketched-in characters that populate the suspect lists of Murder on the Orient Express, Three-Act Tragedy and even Death in the Clouds. Sure, there are terrific characters – Mrs. Hubbard, Sir Charles Cartwright, and Mr. Clancy immediately come to mind – but a definite change occurs in the three novels published in 1936. In both The A.B.C. Murders and Cards on the Table, Hercule Poirot creates a psychological profile of the killer and profiles each of his suspects enough to decide who is innocent and who is capable of a certain type of murder.

As far as characterization goes, Murder in Mesopotamia is a mixed bag between the usual tropes and this newer, richer sort of character. While there are arguably too many suspects here, many of them make fascinating company. This is more true for the women than the men. The three lads who act as “possibles” for William Bosner are quickly delineated as “the Wodehouse one” (Bill Coleman), the one most like Max Mallowan (David Emmott), and the “most likely suspect because he’s German” (Carl Reiter). It’s a wealth of dubious riches, and it’s significant that Reiter and Emmott are cut from the David Suchet adaptation, as is Dr. Giles Reilly, a hugely enjoyable but admittedly unnecessary character.

More interesting are those that might have alternative motives to the Bosner impersonation: Mr. and Mrs. Mercado, at odds with Louise and everyone else due to his drug addiction; the dashing Richard Carey, as much afraid of Louise as he is obsessed with her; the kindly but jealous Miss Johnson; and the fake cleric, Father Lavigny. None of their characterizations are particularly deep, but they are better differentiated than the passengers on the Orient Express or the party guests at Gulls Point, and their motives are suitably mysterious and ultimately more believable than the real one!

Often, Christie achieves her best with her depictions of the victim and the killer. Here, at least, she scores one triumph. Louise Leidner is a masterpiece of psychological neurosis, a woman alternately pitiable and unsympathetic. It’s frankly shocking that Katherine Woolley didn’t recognize herself in Louise. Both are beautiful women who suffered a tragic first marriage. Katherine’s husband killed himself within six months of their wedding. The fate of Louise’s first husband is the stuff of thrillers: Frederick Bosner turns out to be a German spy, and a conflicted Louise turns him in to her father, who works conveniently in the War Office.

Of course, he didn’t die: Bosner escaped in a train wreck that killed the real Dr. Leidner, took the man’s place, established himself as a foremost archaeological authority in America (raise your hand when you start to scoff), and led one expedition after another over the next thirteen years, all the while keeping tabs on his wife in England, sending her threatening notes whenever she went out on a date, and keeping her a grieving (and single) widow until he determined to woo her and marry her again, only as someone else.

The key to explaining this ridiculous scenario is to focus on Louise’s incredible self-absorption. She is so focused on being the center of attention that she can’t identify her enemy even as she shares his name and, one might imagine occasionally, his bed. But then, maybe like Katherine and Leonard, the Leidner’s marriage is essentially sexless. Eric’s need to possess Louise does not include physical passion. (Hands raised!!) Being a victim of Bosner’s long-term persecution has had an effect on Louise’s emotional state. She likes to “stir the pot” and has antagonized many of the residents of the expedition house. “Lovely Louise,” commands men’s attention and then keeps them at arm’s length – all except for Richard Carey. At the same time, she loves her husband and depends upon his strength and protection – but it feels like a daughter’s love for a father figure.

Another great character, Sheila Reilly is almost as difficult a person as Louise, albeit for more innocent reasons. Her relationship with her father mirrors that of the Leidners, again with far more innocent overtones. One of the better jokes in the novel is Amy’s reticence to show Dr. Reilly her manuscript because she can’t help but describe Sheila as something of a bitch. The punchline is Reilly’s response to this: “. . . as children criticize their parents freely in print nowadays, parents are only too delighted when their offspring come in for their share of abuse!”

Finally, we have Amy Leatheran, a significant figure for being one of only three female narrators in the canon. But Amy’s narrative is marked by little in the way of personality, other than her sense of inadequacy about her own writing. We don’t learn much about her past or, after the fact, her future. Still, she is a nurse, a profession Christie respected, and this gives Amy the observational skills required in the reporting of a criminal case and perhaps more empathy than one might expect from Captain Hastings or Luke Fitzwilliam.

What?

- “Dr. Leidner sprang to his feet. ‘Impossible! Absolutely impossible! The idea is absurd!’

- “Mr. Poirot looked at him quite calmly but said nothing.

- “’You mean to suggest that my wife’s former husband is one of the expedition and that she didn’t recognize him?’

- ”’Exactly.’”

Hoo boy! The bulk of the plot rests on this lunatic assumption, although nobody will know how ridiculous it really is until the end. A rational reader will figure out that it can’t be true. The killer must be Frederick Bosner’s younger brother, William – but that means he is one of that trio of indeterminate young men, and Christie seldom hands us such an unprepossessing figure as the murderer at the end. So maybe Louise was killed because of jealousy (one of the women) or because she knew something (Mercado’s habit? The thefts around the tell?) or because Richard Carey, her lover, had grown weary of her. The only person it can’t be is Dr. Leidner. He’s too saintly, and he has a perfect alibi.

Surely that should give the whole game away!

When and where?

“. . . nothing like a road – just a sort of track all ruts and holes. Glorious East indeed! When I thought of our splendid arterial roads in England it made me quite homesick.”

I just want to discuss the Christie Time Frame a little here:

If this narrative was written four years after the events that occurred at Tell Yarimjah, then Poirot must have solved this case on the same trip but earlier than, his adventure on the Orient Express. He comes upon the case after settling a crisis for the Syrian government. After handing over the killer, he travels to Aleppo, where he saves the hide of the French military. He then journeys to Istanbul for a well-deserved rest, only to be summoned back to England due to long-standing “important business” – which brings him on board a certain famous train. After, I presume, righting things for the Crown, Poirot takes a busman’s holiday to Cornwall to settle Sir Charles Cartwright’s hash, flies over to Paris and gets stuck with a murder on the flight back, and then, as Amy Leatheran’s manuscript is hitting the bookstore shelves, Poirot is saving England from a serial killer then solving the murders of Mr. Shaitana and Emily Arundell – all before returning to the Middle East for two busman’s holidays, one in Egypt and the other in Jordan.

And he’s “retired?”

As for the place, Christie never gives us mountains of description, and yet the gift of her travel writing is in how it keenly reflects her personal reactions to each place and experience. Thus, we get to know Hassaniah through Amy Leatheran’s reactions to each stage of it, from the bumpy ride she takes with Bill Coleman from the train station to Tell Yarimjah to her final summing up after the case is over:

“I’ve never been out East again. It’s funny – sometimes I wish I could. I think of the noise the water wheel made and the women washing, and that queer haughty look that camels give you – and I get quite a homesick feeling.”

Some people criticize Christie’s economy of description, but after you’ve read Murder in Mesopotamia, you have a surer sense of the life Christie experienced in an expedition house at one of her husband Max’s jobs. It’s one of the richest environments Agatha ever gave us.

Score: 8/10

The Solution and How He Gets There (10 points)

Poirot’s relates his solution to the case over two chapters spanning thirty pages of text. Most of his lengthy monologue involves jumping from one suspect to another and pondering the possibility of their guilt without necessarily eliminating them. In the end, the sleuth pieces together the truth – that Eric Leidner, alias Frederick Bosner, killed his wife by luring her to her bedroom window with a dangling mask and then hurling a heavy quern at her head when she popped it out the window. He then pulled the quern, through which he had threaded a rope, back up onto the roof, worked another hour to confirm his alibi, and then “discovered” his wife’s body, taking the time to switch a bloodstained rug and close the window.

Poirot essentially uses three clues to put all this together, and all of them come from the unfortunate Miss Johnson. First, she says she heard Louise give a faint cry before her death. Second, she figures out how her beloved boss could have been the killer by standing up on the roof and looking down at Louise’s window. And, finally, with her dying breath, she gives this message to Amy: “The window – nurse – the window!”

Poirot experiments and figures out that Louise’s window must have been open when she died; otherwise, Miss Johnson couldn’t have heard the cry. And yet the window was closed. This is the best clue in the book, although it can’t possibly imbue Poirot with the entire truth. He has to do some guessing up on that rooftop, but I suppose it’s natural to then suspect the only person who was up on the roof the whole time, establishing a perfect alibi.

If you ask half my friends – or if you check out John Goddard’s invaluable analysis of the book in Agatha Christie’s Golden Age, a lot of folks have trouble believing that Louise would respond to the mask by sticking her entire head through the bars of her window and thus allowing Leidner to drop the weight on her head. Some question the bars being wide enough – but they must have been. I tend to look at it more psychologically. Seeing the “spirit” that has frightened her several times at night in broad daylight and realizing it’s a trick, why wouldn’t Louise run out of her room and go up to the roof? Or circle the Tell? Or sound an alarm? Leidner’s plot calls on his wife to make the weirdest choice! How could he have been sure she would do this?

It is close to absurd that Poirot could have deduced the truth from these paltry clues. Goddard makes a further point that Poirot finds enlightenment on the roof before he finds the weapon, an object of which the reader was never made aware until it is found. John argues well that Christie may have laid a path for Poirot to find out the solution, but here she most certainly did not play fair with the reader.

Score: 5/10

The Poirot Factor

“’(Poirot) lives in London, true,’ said Dr. Reilly, ‘but this is where the coincidence comes in. He is now not in London, but in Syria, and he will actually pass through Hassanieh on his way to Baghdad tomorrow . . . it seems he has been disentangling some military scandal in Syria.’”

What a lucky break for the case that Poirot is in the area! I’m perfectly happy that he is here, but he shows up later than for any case to date, fully a third or more of the way into the book. That means rehashing all that has gone before, and while he makes use of Amy’s powers of observation, he never takes her into his confidence or treats her like a Watson figure. In fact, there are a lot of people Poirot works with here – Amy, Dr. Reilly, Colonel Maitland, Dr. Leidner – and yet he remains more removed from the group than usual. He is very much a hired consultant, the traditional outsider detective, and I suppose his little grey cells are needed to sort out the killer’s plot – and yet . . .

I can’t help thinking that Amy Leatheran would have left a much more interesting legacy in our minds had she solved the case – or perhaps she could have worked side by side with Dr. Reilly and then married the fellow and been done in one. People argue that Hercule Poirot didn’t need to be in The Hollow or Cat Among the Pigeons, but I find his presence in those cases far more fascinating and, indeed, necessary than his presence here.

Score: 6/10

The Wow Factor

Murder in Mesopotamia is a lot like the archaeological dig upon which it is set: there are a number of interesting finds, but the whole thing is a bit dusty. We’re definitely seeing more character development than we’re used to. Christie gives us a female narrator and a wealth of details about the day-to-day lives of men like her husband Max.

If you read your Dr. Curran, you’ll find that the book seemed to come easily to Agatha. It comprised a mere fifteen pages of notes and didn’t involve much speculation as to alternate scenarios about who- or howdunnit. In fact, Christie seemed excited about placing what she called “the window idea” into this story (she even drew a chart!), and the murder method is probably the most distinctive thing about the book. It’s also a perfectly legitimate example of the impossible crime – if you are willing to accept that Louise would stick her head all the way between the bars and look up to find the source of the offending mask.

Unfortunately, Christie’s choice of killer, while certainly audacious, is ultimately unbelievable. You can argue that lots of classic detective novels got this crazy! I would counter that this is the solution more Christie fans shake their heads at than any other. Agatha was going for “Wow!” and ended up with “Wha-?!?”

Score: 5/10

FINAL SCORE FOR MURDER IN MESOPOTAMIA: 30/50

THE POIROT PROJECT RANKINGS SO FAR . . .

- The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (48 points)

- The A.B.C. Murders (46 points)

- Three-Act Tragedy (42 points)

- Cards on the Table (36 points)

- Death in the Clouds (35 points)

- One, Two, Buckle My Shoe (34 points)

- Murder in Mesopotamia (30 points)

- Dead Man’s Folly (28 points)

- The Mystery of the Blue Train (26 points)

- The Big Four (21 points)

Next time . . .

We dive into the private life of Miss Lemon! Does it all go downhill from there? Stay tuned!

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX | Ah Sweet Mystery!

I’ll agree that Louise not recognizing her husband is hard to believe and yet, I don’t know.

Keep in mind that we’re TOLD that Louise isn’t a sensualist.

When she marries hubby #1, she’s probably (IIRC) a well-connected, properly brought up, 19-year-old virgin Edwardian young lady, emphasis on the lady. Not woman. Lady. A different species. It’s quite likely that she had little idea of what sex was. OUR society is so sex-soaked (I just returned from Write Women Book Fest 2025 and my word!) that it’s hard to understand how different the past was.

Thus, Louise marries the dashing young man and quickly discovers that she doesn’t like being under some man’s thumb and she doesn’t like sex, which consists of awkward fumbling in the dark under a blanket with her eyes closed while she thinks of America.

Again, a very different mindset from 21st century America. Or England. Some of the memoirs of ladies of that period are quite astonishing in how much they didn’t know.

Then, within a few months of her marriage, Louise discovers that she can get rid of a husband she does not want AND she can be the patriotic heroine because said husband is a German spy. Everyone approves! What a brave girl, doing her duty for God and Country!

Louise is free. She does not remarry. She doesn’t, apparently, carry on physical affairs. Emotional affairs or affairs of the mind where she holds the whip-hand? You bet. But not getting naked and sweaty in the sheets.

When she meets hubby #2, would she really recognize a man she was with for only a few months 20 years before? A man she did her best to erase from her mind, including those distressing, awkward, animalistic fumblings in the dark that decent ladies wouldn’t dream of doing?

I could see it. There are none so blind as those who will not see.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sure, I could see it, too . . . if only Agatha had written it that way!

There’s a gap of twelve years, not twenty, between the marriages. During that time, Louise sought out male company but ran away because of the threatening letters she would receive each time she got close to a man. Perhaps her marriage to Eric was intellectual and non-sexual; we’ve only got the Woolley parallel to give us a hint about that because Christie wouldn’t be so brazen with details. But Louise, at least, is strongly physical, as we see with Richard Carey.

We can draw whatever line of believability that we like with classic crime fiction, explaining away whatever outrageous features we come across. (Read J.D. Carr’s The Crooked Hinge, which I have no trouble embracing!) Generally speaking, I think people would have a

Lot of trouble buying the recognition factor here. Even the bloom of young love is about more than sex, and disguising yourself 24/7 from a wife you married before is harder than it would seem!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suppose I’m reading some of my own reading and experiences into the story!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good Lord! Did you marry Bill twice?!? Have you just realized it?!?

LikeLike

Hah! No, but if I was forced to remember some past boyfriend from long ago, I wouldn’t remember much. And I’m a modern woman, not some fainting Edwardian flower whose never done more than hold hands or share a dance.

I think of some of the Victorian stuff I’ve read. It seems that the higher the woman’s social status — until you reached the aristocracy where anything goes because who cares what you respectable plebes think — the less she knew! Farm girls knew because it was unavoidable as did anyone poor, because you’ve got too many people crammed into too small rooms. Plenty of prostitutes patrolled the streets, too and they weren’t shy.

I think that the Victorians were as prudish as they were (think of John Ruskin) because sex was everywhere in the streets. Their attitudes had to come from somewhere.

People don’t get worked up over things they don’t care about and can ignore.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m one of those who’s bothered by the mechanics of the barred window. Yes, the husband thing is far stupider, but bars you can fit your whole head through? Walls that are thin enough that even if you can fit your whole head head through the bars, enough then protrudes beyond the wall that the murder weapon can do the deed and not seem to have caused two wounds – where it hits her and the other side of her head as it smashes into the window sill. And that the bars are soooo wide that she just falls back into the room…

I could go on…

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is precisely why I designed my own home with thin walls and wide bars, in case any of my guests displeased me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Did you receive your copy of “International Agatha Christie, She Watched?”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I did. I’m reading it now.

LikeLike

Excellent! I always worry about the post office making deliveries. Silly, I know.

I do mention you here and there, too!

LikeLike

That All About Agatha ranking is shocking.

How did Dumb Witness end up behind this (I struggled with this one a lot from memory)? I clearly need to listen back to those episodes again to hear some reasoning!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dumb Witness has its own problems (I.e., the dumbest clue in the canon), but it has great characters and one of the best incarnations of Hastings, who is slightly dumber than Bob the dog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If I remember their episode about Dumb Witness correctly, they really disliked the beginning of the novel and thought it dragged on forever. They said it was the longest novel so far and didn’t need to be.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Ironically, the beginning is my favorite part of Dumb Witness: the hook is effective, and the early scenes where Poirot and Hastings are interviewing villagers to get information about the Arundells is really well done. (Great villagers!!)

LikeLike

I too consider Christie’s And Then There Were None her most impressive sojourn into the world of impossible crime. I’m somewhat surprised by the unwillingness of some to accept it into the category, merely because the apparent impossibility is so short-lived— don’t they realize that the very slightest aspect of impossibility makes an entire world impossible? Somehow, framing this idea in a work of fantasy (the modern penny in Sonewhere in Time, the ring in Peter Ibbetson) makes the concept more easily comprehended.

With a work like Murder in Mesopotamia, I’ll admit that the glaring improbability of the solution (I’m taking about the forgotten husband aspect, not the barred window) diminishes my enjoyment of the work. But I think it’s somewhat a function of Christie not doing very thing she could to minimize the sense of improbability. I also think it’s interesting that ridiculous coincidences of The Bishop Murder Case and those of He Who Whispers— both of which I think make Mesopotamia seem like unremarkable realism by contrast— don’t receive the same level criticism (don’t get me wrong— I LOVE He Who Whispers- but it takes a helluva lot to swallow).

I also find it odd that most of the analysis of the Mesopotamia implausibility centers on the issue of sexual intimacy. As intimate as sexual intercourse is, I don’t know whether it’s the strongest indicator of individual identity— especially in an era and country in which restraint of behavior was probably present even in those actions (and lights were DEFINITELY kept out).

LikeLiked by 2 people

I always giggle when you talk about The Bishop Murder Case and the fortuitous circumstance of EVERY neighbor having a name that corresponds with the killer’s favorite nursery rhyme. It makes the plot of And Then There Were None seem like Neo-Realism!

And, yes, that’s my point: I don’t mean to get crass here, but we’re talking about more than recognizing a man’s penis!! There are other intimacies you share with a loved one: intimacies of conversation, looking in their eyes, their scent, their idiosyncrasies . . . they become warmly familiar and you remember those things.

LikeLike

Impersonation / disguises are rarely convincing anyway (almost any film or TV example you care to mention is revealed as utterly transparent within seconds after all). But an individual”s scent, laugh, voice, personal habits, physical characteristics etc etc would be impossible to miss. How much more interesting it would have been to suggest she knew all along and it was all part of an elaborate role play / charade between them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

She could have accepted his new identity as payback for having turned him in as a spy, or because her father had gone against her wishes and arrested him. One of the stories in the NEW Marple story collection plays around with this idea – and it works.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Does not Styles start in a similar way with Hastings explaining he is writing up the case to dispel som confusion in the media? (Ackroyd noticeably has no such explanation.) I can easily believe that once the solution was known this case would attract media attention. (Less convinced that Styles would do it.)

I think the mechanics of luring Louise to the window could have been made more realistic, if it was a note or something. Maybe we could have been told her husband was in the habit of sending love notes to her in strange ways.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hastings speaks not of confusion, but of “intense interest”, and “worldwide notoriety!” He wants to write his account to “silence the sensational rumors. Like you, I’m not convinced that the Styles case would have generated any of this!!

LikeLike

I am wondering if perhaps the bars were widely spaced than we might expect. Went down a Google rabbithole to see what the house Agatha lived in in Iraq might have looked like and came across this interesting article. The house still exists! https://shafaq.com/amp/en/Report/Historic-Baghdad-house-of-Agatha-Christie-nears-ruin I zoomed into every picture and one of the upper floor windows looks like it may not have proper bars. Perhaps the narrow bars were put in later. Given that she drew from so many of her own lived experiences for this book, perhaps the house too is based on the house she lived in. Anyway, a fun fifteen minutes for me. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, first of all, what a wonderful sojourn that must have been for you! I’m willing to accept that the bars were wide enough to get a head through; it’s still awkward to think that her head stuck out far enough to be hit. Plus, it would do Louise no good to look down, so she would have to twist herself fully around to look up. MUCH easier to slip outside and walk the few yards it would take to check the roof!

LikeLike

It’s not a very good book – even as a kid, much as I enjoyed the physical “thwack” of the murder method, I knew it was basically absurd. But your excellent and witty critique makes it all worthwhile. Thanks Brad.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #11: Hickory Dickory Dock | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Which story did Father Eric Burrows inspire?

LikeLike

If you asked me which character in THIS book Father Burrows inspired, the obvious answer would be Father Lavigny, as both men translated ancient religious texts. As to another story, I’m afraid I have no idea.

LikeLike

“She meets Father Burrows, a Jesuit priest and the resident epigraphist, who actually gave her an idea for a mystery story that she would turn into her own a quarter century later…”

LikeLiked by 1 person

If it’s not this very novel, I’m not sure. Janet Morgan mentions him in her Christie biography as part of the same expedition where she met Max. Is there another story you’re thinking of?

LikeLike

From your review, above: “gave her an idea for a mystery story that she would turn into her own a quarter century later…”

LikeLike

So which mystery story did Agatha write based on an idea of his?

LikeLike

Agatha speaks of her meeting with Father Burrows in her Autobiography. She says he laid out details of a plot that she ended up using in, not a novel, but a long short story. Unfortunately, that is the only clue she gives us as to what that story was.

LikeLike

Thanks so much! – I searched online, as well as my two Curran books, three Aldridge books and Agatha Christie Companion by Bernthal and found nothing.

Now I need to pick up her autobiography.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #12: Elephants Can Remember | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #13: Hallowe’en Party | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #14: Death on the Nile | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #15: Peril at End House | Ah Sweet Mystery!