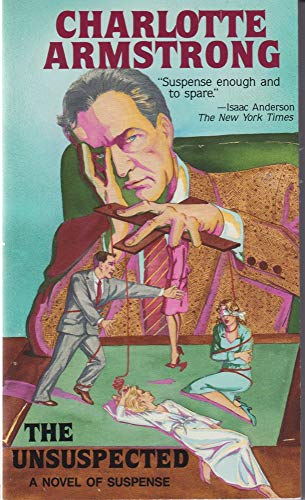

Had Charlotte Armstrong decided that she would become the beloved author of sixty-six cozy mysteries starring her beloved amateur sleuth, retired history professor MacDougall Duff, I have a feeling we would not be talking about her now. Or perhaps Dean Street Press would be slowly republishing her long-forgotten canon. (Not to snark on Duff: I have one of his three cases, The Case of the Weird Sisters, lying around here somewhere and will check the guy out for myself . . . one of these days.) But that’s not what happened. Instead, Armstrong’s agent told her to lay off Mac Duff after three books and try something new. The result, 1946’s The Unsuspected, set Charlotte Armstrong in a new direction as a Queen of Domestic Suspense.

After my great success earlier this year with The Chocolate Cobweb, Armstrong’s 1948 follow-up to The Unsuspected, I was eager to return to the author. Both books have been reissued by Otto Penzler for his American Mystery Classics series, and both had been occupying space on my TBR shelf for far too long. Plus, I wanted a reason to rewatch the 1947 adaptation of The Unsuspected, which is playing on Turner Classic Movies tomorrow morning/afternoon, depending on where you live! As it turns out, book and movie are different kettles of fish . . . but more about that later.

Penzler himself provides a short introduction to the book that is packed with interesting facts and observations. He notes Armstrong’s description as “the leading moralist in the mystery writing community” and the contrast with many of her contemporaries, like Margaret Millar and Patricia Highsmith. While all three authors create deft portraits of abnormal psychology, Armstrong focuses on “sane, decent people who find themselves in difficult situations or are trying to protect the innocent, and who emerge triumphant because their fundamental decency will defeat the evil antagonists with whom they battle.”

The book was a huge success (proving you should always listen to your agent!), but the critical response was mixed. Penzler suggests that critics were upset at the reveal of the killer’s identity almost from the start because they were not aware of the conventions of an inverted mystery. This, despite a long train of popular books in that sub-genre by the likes of Berkeley, Croft, and Sayers!

Maybe Penzler is right, but I have to say that throughout my read – my highly enjoyable read, mind you! – I felt that the structure of the book was weird!! It finally occurred to me that the whole story feels like one long climax: we’re plunged into the situation with hardly a how-do-you-do, and big things keep happening without letting us catch our breath. Plus, Armstrong keeps switching our perspective, albeit in a fascinating way, between various good people – and one very bad one. Naturally, to lend much description to what happens will spoil far too many of the book’s pleasures, so I’ll keep this brief:

Rosaleen Wright, a bright and beautiful young woman, has evidently hung herself in the office of her employer, the beloved retired theatrical impresario Luther Grandison. But two people refuse to believe Rosaleen capable of suicide: her fiancé Francis, recently returned from overseas with war injuries and a broken heart, and the bright and beautiful Jane, who has pieced together evidence that Rosaleen not only did not take her own life but was murdered. And Jane is certain of the killer’s identity: Grandison himself. On an impulse, she gets herself hired in Rosaleen’s place as the old man’s secretary.

Meanwhile, Francis has his own plan for infiltrating the menage: Grandison has two young wards, poor little rich girl Mathilda and just-poor-but-gorgeous Althea. Mathilda was engaged to marry Oliver, but Althea stole him away. The heartbroken heiress decided to drown her sorrows on an ocean cruise, only to simply drown when the boat went down. Francis proposes that he will impersonate Mathilda’s new husband, worm his way into Grandison’s affections, and help Jane find the proof that he killed Rosaleen.

Except . . . Mathilda isn’t dead at all. She was rescued at sea and is making her way back home to her beloved Grandy – and to the “husband” she never knew she had!

And this is only the first three chapters!! It’s to Armstrong’s credit that she takes this almost ridiculous set of circumstances, moves them forward with deft pacing and sustains them (pretty) believably. There’s about six times as much plot contained here as there was in The Chocolate Cobweb, and while I was more likely to raise my eyebrows at each reshuffling of alliances or plot twist, I was having too much fun to complain. Perhaps Luthor ultimately didn’t send shivers down my spine the way the villain in Chocolate Cobweb did, but then we never get inside his head, even as Armstrong poses no doubt that he’s a bad ‘un. Far more chilling are Luthor’s minions, the tortured Mr. Press and his wife, a sour-faced woman who gets a great charge out of inflicting pain.

What I appreciate about Armstrong is how psychologically astute she is in her creation of good people. We root for Jane and Francis and Mathilda, even as they are mostly at odds with each other till the very end. In addition to finding evidence of Grandison’s crimes, Francis and Jane must also “deprogram” Mathilda – and the cops and Grandy’s adoring public – in order to expose the evil within. It’s no easy task, and it places both of them in terrible danger, leading to a climax where Armstrong ratchets up the suspense to the breaking point. And if I tell you that things end on a happy note for most of the characters, don’t feel like I’ve spoiled things for you. After all the darkness at the end of a tunnel manufactured by the likes of Woolrich or Highsmith, it’s nice to put ourselves in the hands of an author who is looking after her good guys.

* * * * *

The 1947 film adaptation of The Unsuspected has a great deal going for it. Director: Michael Curtiz, one of the greats, with over 175 films spanning every genre and including classics like The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), Casablanca (1942) and Mildred Pierce (1945). Cinematographer: Woody Bredel, who was born for film noir and who gave us the best (Phantom Lady) and made the worst (Female Jungle) stylish. Stars: well, it was supposed to be Orson Welles (too busy trying to save The Lady from Shanghai), or maybe Robert Alda or Humphrey Bogart. Luckily, Curtiz ended up with Claude Rains as Luthor Grandison, here renamed Victor. And when he couldn’t afford Joan Fontaine to play Mathilda, Curtiz cast Joan Caulfield, who may not have achieved Fontaine’s stardom but was perfectly cast here.

Then there was hero Francis Howard – or, rather, “Stephen Francis Howard” as he was renamed here. Curtiz thought it would make for great publicity to debut a hot new actor in the role, and so he cast an actor named Ted North. The only problem? Ted North had already made twenty pictures, the last one “The Devil Thumbs a Ride,” that same year! Curtiz convinced North to change his first name to Michael, and the credits feature the shot “and introducing Michael North.” The only problem? North never made another film. Meanwhile, Curtiz made no hay about an actual film debut, that of Fred Clark in the role of the homicide inspector. Any Boomer would take a look at Clark’s mug and swear he had seen that face hundreds of times – as Sheldrake in Sunset Boulevard, Mr. Babcock in Auntie Mame, and in virtually every sitcom in the 50’s and 60’s!

The screenplay, co-written by Curtiz’ wife, was clearly inspired by the director’s admiration for 1944’s Laura; there’s even a portrait of Mathilda hanging in Grandy’s studio at which everyone can hurl meaningful gazes. Curtiz wanted to make a film just like Laura, which may explain why we find ourselves with a more traditionally structured mystery than in the book. We’re a third of the way in before it becomes clear that Grandy is the villain. Meanwhile, the film mines more out of Francis showing up and announcing he was married to the “dead” Mathilda. His motivations, as well as his conspiracy with Joan to solve Rosaleen’s murder, are kept hidden for nearly half the film.

Victor is no longer retired but a huge radio star known for his chilling crime stories. Joan is his producer, and she is played by Constance Bennett, doing her best Eve Arden impersonation. (Curtiz wanted Arden but didn’t get her.) The film mines the most fun out of Althea and Oliver. Audrey Totter gives a sizzling performance as the slinky niece, and the screen lights up whenever this doomed femme fatale appears. Oliver is played by Hurd Hatfield as a moody drunk, and he gets the best line in the movie when Mathilda, newly returned from beyond the grave, is standing before her portrait and Grandy says that she has changed. Hatfield, the star two years earlier of The Picture of Dorian Gray, fixes the portrait with a haunted stare and says, “No, Grandy, Mathilda hasn’t changed; it’s the picture that has changed.”

As with all adaptations, the film tosses out book characters and some wonderful details, but it still manages to give us an entertaining semblance of Armstrong’s book. It’ll never make the list of top films noirs, but thanks to Rains, Totter, and Bennett, it’s a hoot to watch.

One of these days, I’m going to locate some of Armstrong’s other top works, like Michief and A Dram of Poison, and give them a read. Meanwhile, The Case of the Weird Sisters is calling to me. Expect my review . . . within the next year or five!

Excellent double review, sir!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a great book, and I’m sincerely hoping I can discover more by her of the quality of this and The Chocolate Cobweb. Time will tell…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Oh #$%&! Not Another Blogger’s Tenth Anniversary!! | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: BECAUSE YOU LIKE THE LISTS . . . Brad’s Top Ten Reads of 2025 | Ah Sweet Mystery!