If experience is any measure, the majority of Perry Mason mysteries begin one morning, afternoon, or evening in Mason’s law office with the arrival of an intriguing new client. Doesn’t sound very exciting, perhaps, but I get a thrill every time it happens. What bizarre situation is the ingenue secretary, eccentric old woman, blonde bombshell, or mining executive going to dump in Mason’s lap, thus saving the attorney the chore of going through his daily mail?

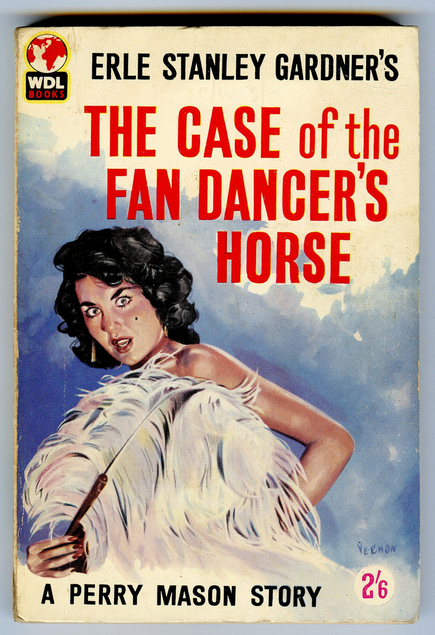

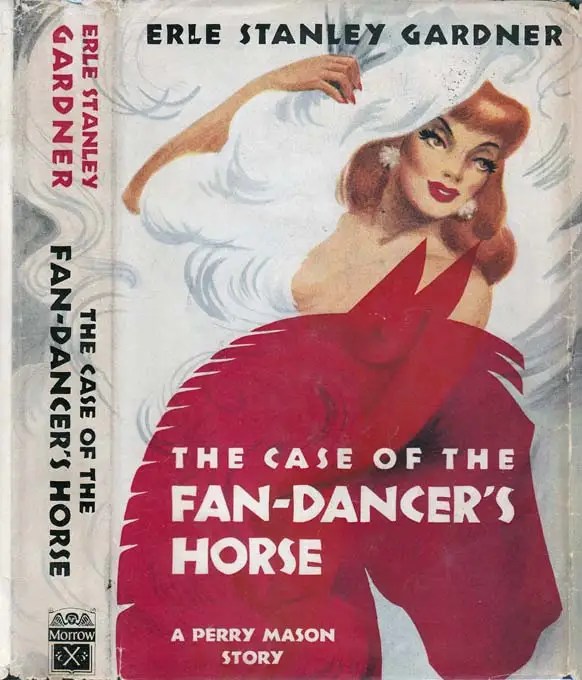

However, the start of 1947’s The Case of the Fan-Dancer’s Horse, our latest visit to the Mason Menagerie, is not only different, it’s positively thrilling. It begins on a highway in the Imperial Valley on “a blistering hot morning” as Perry Mason’s ride with Della Street is disrupted by a large sedan passing at such a speed that it causes the lawyer’s car to sway on its springs. Another car in the sedan’s way is not so lucky: “Fenders seemed only to have given a gentle kiss, but the northbound car went out of control, teetered on two wheels, swerved off the highway into the hot sand, and rolled over.”

Ever the Good Samaritan, Perry stops to give assistance and finds the driver to be an elderly Mexican woman who has managed to survive with little more than a broken arm. She seems nice but not very communicative, and when another passerby offers to drive her to get medical help, she abandons her car and takes off. Looking for the registration certificate to see who the owner is, Perry opens the trunk and finds a pair of dancing slippers and two high-quality ostrich-plume fans, bearing the initials “LF.” Mason recognizes the garb of a fan-dancer (perhaps any healthy adult male living in 1947 would do the same!), but when he checks with the police, he finds that no accident has been reported and that the car was stolen.

The next morning, faced with the usual stack of boring mail, Mason decides he’d rather go looking for fan-dancers. He places an ad in the paper and receives a grateful response from a woman named Lois Fenton, who goes by the stage name “Cherie Chi-Chi!” (Coincidentally, that was my own byline on my junior high school newspaper!) Lois informs Mason that a man acting as her agent will visit him to retrieve her lost property. But that property turns out to be not ostrich fans but a missing horse, a seven-year-old chestnut gelding with fine markings and possibly one marking that’s not so fine: a bullet wound. And not one, but two men arrive acting as agents for Lois Fenton. Soon enough, Perry figures out that there are two fan-dancers named Lois Fenton, a.k.a. Cherie Chi-Chi, and that something funny is going on with the feathers and the agents and the dancers and the horse!

It all culminates, as you might expect, with a dead man in a hotel room, this one run through by his own Japanese sword. On the plus side, his room was being watched by Paul Drake’s men, but that only leaves Mason with a rundown of visitations to the victim that would rival a Freeman Wills Crofts alibi schedule.

It’s a tight little problem, and Gardner has fun with the salacious aspects of Lois’ profession. But I have to say that, after the complexities and epic sweep of our previous outing, The Case of the Drowsy Mosquito, this case feels like a bit of a palate cleanser. The cast is small, and for some reason, Gardner keeps the major players off the page most of the time. It gives the middle section of the book, from the murder to when Perry steps into court at the top of Chapter Eighteen, a static feel as Mason and Drake try to sop up as much information as they can.

With that said, the trial itself is fun: more than once, Perry has used doubles to try and confound Hamilton Burger and the jury; we saw it done beautifully with parrots a few reads ago. A reader would naturally jump to the conclusion that this case of the double fan-dancers would be the perfect time to pull that trick again, so imagine Mason’s frustration when the D.A. stymies his efforts. This, however, leads to an interesting twist that reveals an act of baser chicanery on the State’s side than any trick to which Mason may have ever stooped. The bonus is that it involves Mason’s old adversary from the 30’s, Sergeant Holcomb.

Unfortunately, while this may assist our hero in freeing his client, it does not lead to any dramatic revelation as to who is the actual killer. That information is hurried past us in the final few pages, and while it’s a perfectly feasible solution, our lack of real acquaintance with the culprit and the rush job of proving him guilty, for once lets us down.

* * * * *

If the book feels like lighter Perry Mason fare after some of the classics we’ve read lately, at least the storyline fits beautifully into an episode of Perry Mason. This one appeared on December 28, 1957, the fifteenth episode of the first, and possibly best, season of the show. It is, beat for beat, a stunningly faithful adaptation of the novel, right down to the inclusion of massive amounts of the book’s dialogue. It even sacrifices the traditional big courtroom confrontation with the killer that was the hallmark of the series in order to stay true to the original plotline.

Judy Tyler, the actress who plays the false Lois Fenton, gives a fantastic performance. She had been a regular on Howdy Doody as Princess Summerfall Winterspring. The same year that this episode aired, she had starred opposite Elvis Presley in Jailhouse Rock. Tragically, in July of that year, she and her husband were involved in a road collision far more serious than the one that starts this episode; Tyler was killed instantly. This episode of Perry Mason, shown six months after her death, was Judy Tyler’s last recorded performance.

Next month, we move to the 1950’s and the bizarre circumstances surrounding a moth-eaten mink! As this was the novel chosen for the pilot episode of Perry Mason, it had better be good!

Pingback: THE ERLE STANLEY GARDNER INDEX | Ah Sweet Mystery!

I just re-watched the episode on MeTV and noticed there’s a THIRD fan dancer in the episode…a professional fan dancer who doubles for both Susan Cummings and Judy Tyler in the dance scenes. No mention of her name in the IMDB credits for the episode.

LikeLike