Today would have been my dad’s ninety-seventh birthday. In the Jewish faith, we believe that those who have passed never leave us – everything we ever loved about them stays in our hearts. I know my father is nearby, nudging me remember to water the plants. He was a brilliant gardener, something I could never be. Yet for the past three years the flowers on my deck have never looked more beautiful or thrived so long. I’ve even coaxed the bougainvillea to exist contentedly – in a pot! Thanks, Dad – and happy birthday!

My father was more of a smiler than a laugher – with one exception. If he turned on the TV and happened upon an Ealing comedy, he would go into such hysterics that we feared for his life. He especially loved Alec Guinness, and watching the star execute a heist that went wrong in The Lavender Hill Mob or The Ladykillers, or play eight doomed heirs in Kind Hearts and Coronets would set Dad off! His laugh was just like his mother’s, a series of extended wheezes, and when he got wound up, it looked like he had stopped breathing! We would pat him on the back and ask him if he was OK, but Dad would shoo us away and go right on wheezing!

The Ealing comedies were a phenomenon that only lasted ten years (1947-1957). They were marked by comedy of the blackest nature, which satirized British manners. Studio head Michael Balcon explained how the films tapped into the British mood of the day: In the immediate post-war years there was as yet no mood of cynicism: the bloodless revolution of 1945 had taken place, but I think our first desire was to get rid of as many wartime restrictions as possible and get going. The country was tired of regulations and regimentation, and there was a mild anarchy in the air. In a sense our comedies were a reflection of this mood, a safety valve for our more anti-social impulses.”

I bring this up because in 1951, at the midpoint of Ealing’s popularity, an eccentric socialite named Pamela Branch, decided to try her hand at writing a mystery. The result was The Wooden Overcoat, and it is as close to reading an Ealing comedy as you can get! My dad would have rather read a desk-size tome about the Civil War than any work of fiction, but if someone had made a movie out of The Wooden Overcoat, I bet it would have set him to wheezing something awful!!

Unfortunately, American publishers at the time didn’t think their reading audience would laugh, and only the final of Branch’s four books was published in the U.S. – until 2006, when the Rue Morgue Press put out all of Branch’s mysteries. They gave Overcoat the subtitle: “A comedy of manners with the occasional murder,” – it’s the perfect description of this truly rollicking farce. Classic Mayhem republished the book in 2024, but I happen to have the Rue Morgue edition, where publishers Tom and Enid Schantz have provided a delightful introduction, despite little biographical material being known about the author. It seems that fellow writer Christianna Brand thought Branch “the funniest lady you ever knew” because she liked to send Brand “countless postcards with smears of pretense blood on them, or a dreadful squashed box of chocolates with very obvious pinholes into which poison had clearly been injected.”

If I were waxing Shakespearean, I might begin by describing the setting of the book as: “Two houses both alike in indignity/Near Battersea Bridge where we set our scene . . . “ In one of these houses, No. 15, resides a sort of artist’s colony, comprised of two couples, the Hilfords and the Berkos. Peter Hilford is a photographer and a writer of mysteries, but like so many crime novelists, after four adventures of Inspector Carstairs, he is eager to kill his creation off. Peter’s wife Fan is an artist, Hugo Berko is a sculptor, and his wife Bertha a weaver. They live in apparent harmony with a lascivious cleaning woman, a truly alarming miniature poodle, and, most unfortunately, about a thousand rats.

Next door, in No. 13, live the members of the Asterisk Club, founded by Clifford Flush, a man of exceeding grace and charm (ignore the gold tooth!) who achieved a modicum of fame in 1937 when he murdered three people on the Southern Railway (the fourth survived) and earned the sobriquet of The Balliol Butcher. He was caught, but wouldn’t you know? – he got away with it!! Now Flush has created a haven for other wrongfully acquitted murderers: an elderly widow, a red-faced Colonel, a Hungarian temptress, and an enormous monster who would have been played in the movies by Rondo Hatton. They all live in as much harmony as a group of psychopaths can muster.

At the start of the novel, Flush has found a new recruit, young Benjamin Cann, who murdered his mistress because she insisted on keeping a bit of the housekeeping funds aside to use as mad money. (As in . . . the money made Benji very mad.) In exchange for bequeathing all his worldly goods to the Club should he ever shuffle off this mortal coil, Benji can find contentment with those who understand him.

Benji is leery about moving into the Asterisk Club, but the Hungarian temptress is very tempting, and so he agrees to sleep on the offer by lodging in a room next door until he makes up his mind. And so he moves in with the Hilfords and the Berkos and the horny housekeeper and the overdramatic poodle, and a new presence – a retired Rodent Officer with an accent so much like Inspector Clouseau that he could only be portrayed in the film version by Ealing regular Peter Sellers.

Okay, I’ve set the scene . . . now it’s up to you to decide if you want to partake of the rest. Because the plot, such as it is, consists of one surprise after another. If you’re a crime fan, there is a murder – more than one, in fact – and there is a murderer who is unmasked at the end. But don’t go into this expecting a conventional mystery! This is pure comic farce, through and through. I kept asking myself whether Alec Guinness should play the fiendish Clifford Flush, or the flummoxed Peter Hilford, but the answer was obvious: he should play both!

Martin Edwards, in his review of another of Branch’s books, calls her writing style “very concentrated,” and I had to read this in small doses. The plot amounts to little more than a huge shaggy dog story about people working at cross purposes to accomplish some very dark things. It’s not usually my sort of thing – and yet, every time I picked it up, I started to laugh. I tried emailing some of the funnier lines to myself for inclusion here, but then I realized that you wouldn’t understand the context of most of the jokes. Suffice it to say that much of the humor is character-driven, and both households crammed crammed with amusing characters. I should have been offended by the stereotypically gay ballet dancer Rex and his horrific friend Bunny, but they made me laugh. “Rex came in. Peter noticed that, as usual, he made an entrance. He flung open the door with an outstretched hand and looked around the saloon bar, as if he were on a hilltop overlooking seven counties. Then he drooped and drifted over to the bar.”

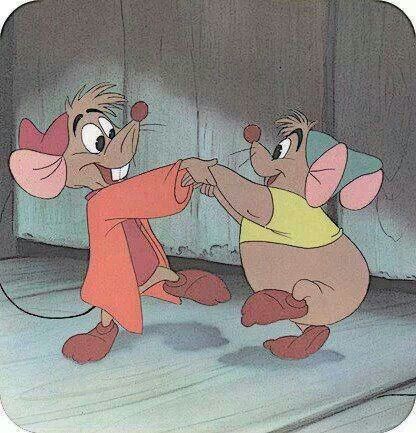

The humor is also brilliantly situational: while each character has a set of qualities that are in themselves funny, it’s the way Branch makes them all react to the increasingly bizarre set of circumstances that befall them that makes this so delightful. Even the animals are funny! (In addition to Croydon, the world’s most melodramatic poodle, there’s Tom, the Asterisk Club’s resident cat – who may be the most evil or the most heroic figure in the story – and a bunch of rats who are nearly as anthropomorphized as they are in Disney’s Cinderella.)

While I may not rush out to find more of Branch’s work – my friend Kate Jackson, who has read three of her four novels, loved this and one other and disliked the third – I really enjoyed The Wooden Overcoat. And I’m especially glad that my Book Club decided to read and discuss it on my dad’s birthday. It makes the whole experience that much more special.