“After an early dinner at which they drank Aunt Jane’s health, they all went off to His Majesty’s theater . . . The lights went down, and the play began. It was superbly acted, and Gwenda enjoyed it very much. She had not seen very many first-rate theatrical productions. The play drew to a close, came to that supreme moment of horror. The actor’s voice came over the footlights, filled with the tragedy of a warped and perverted mentality. ‘Cover her face; mine eyes dazzle; she died young.’ Gwenda screamed.”

The illusions created on a theatre stage can exercise a powerful effect over our emotions or, as they did to Gwenda Reed in Sleeping Murder, unleash long-buried memories. Agatha Miller, the future creator of the scene above, had a childhood full of theatrical experiences of her own making. Born ten and eleven years, respectively, after her older brother and sister, young Agatha, although much loved, was day to day left largely to her own devices. She loved Ashfield, both the house she lived in and the garden in which she played. Lucy Worsley speaks of her joie de vivre and “high spirits,” even in solitude. In fact, “Agatha was happy alone, making up stories, inventing pretend friends.”

Laura Thompson goes further: “Agatha never thought of herself as lonely. Such an idea would not have occurred to her. She treasured solitude, and the space it gave her for other lives. She also treasured privacy; when she overheard her nurse discussing one of her earliest imaginary games with a housemaid, (‘Oh she plays that she’s a kitten with some other kittens’), she was upset to the core.” According to Agatha herself, her mother Clara did not believe in young girls being conventionally schooled but instead followed the philosophy that “the best way to bring up girls was to let them run wild as much as possible; to give them good food, fresh air, and not to force their minds in every way.” This did not stop her daughter from inventing a school of her own and inhabiting it with a whole slew of imaginary girlfriends. There was Ethel Smith, “clever, good at games . . . and rather masculine”; Annie Gray, who was “shy and nervous and easily reduced to tears”; and the “rich, worldly” Isabella Sullivan, whom Agatha disliked very much.

As her private schoolhouse grew in population, one can only imagine the dramatic events that occurred during each “day of instruction.” One of the girls, Sue de Verte, “curiously colorless” both in appearance and behavior, was actually the “role” Agatha played herself: “I was always Sue conversing with them, not Agatha; and therefore, Sue and Agatha became two facets of the same person, and Sue was an observer, not really one of the dramatis personae.” Later on, we’ll explore the many characters who took on roles and disguises for a wide range of purposes.

In fact, many of Agatha’s games involved role-playing, to delightfully sinister effect. She played a game called “The Elder Sister” with her sister Madge, who was not only a good sport but a good actress. “The theme was that in our family was an elder sister, senior to my sister and myself. She was mad and lived in a cave in Corbin’s Head, but sometimes she came to the house. She was indistinguishable in appearance from my sister, except for her voice, which was quite different. It was a frightening voice, a soft, oily voice. ‘You know who I am, don’t you, dear? I’m your sister Madge. You don’t think I’m anyone else, do you? You wouldn’t think that?’”

Perhaps the most significant imaginary figure in Agatha’s life, for our purposes, at least, was The Gunman. He began to appear in her nightmares when she was five. In her Autobiography, Agatha gives us a description of this mythic figure – “The gun was part of his appearance, which seems to me now to have been that of a Frenchman in grey-blue uniform, powdered hair in a queue and a kind of three-cornered hat, and the gun was some old-fashioned kind of musket.” The Gunman terrifies Agatha not because she fears he will shoot her but because of his “mere presence” which tended to take place in the most ordinary of situations, “a tea party, or a walk with various people, usually a mild festivity of some kind. Then, suddenly a feeling of uneasiness would come. There was someone – someone who ought not to be there – a horrid feeling of fear . . . “

I’m sure many of us have dim memories of a similar figure who haunted our dreams. He might be based on a person who startled you in the street, a figure you glimpsed on a screen or conjured in your head after hearing a story. The Gunman becomes even more significant as Agatha grows older, and the dreams change: “Sometimes as we sat around the tea table, I would look across at a friend, or a member of the family, and I would suddenly realize that it was not Dorothy or Phyllis or Monty, or my mother or whoever it might be. The pale blue eyes in the familiar face met mine – under the familiar appearance. It was really the Gunman.”

Lucy Worsley makes a significant connection between these childhood figures and Agatha’s career: “In the ‘Gun Man’ and the ‘Elder Sister,’ Agatha imagined her own mother and sister becoming strange and horrible. They are important, these childhood fantasies, because they illustrate something that would be particularly modern about Agatha’s detective fiction. In Sherlock Holmes, for example, the criminal is often far outside the social circle of the victim. And yet, in Agatha Christie, the murder was often a trusted family member.”

Christie’s fiction is filled with families like her own: parents both caring and querulous, sisters bound by love and jealousy, brothers who are bounders, closed circles of travelers and work associates and partygoers, even schoolgirls much like Ethel, Annie, Isabella and Sue. They may resemble people we know in everyday life, but their own inner lives are teeming with hidden drama, with secrets bursting to get out, often in the most theatrical of ways.

* * * * *

By the time she made her first trip to see a play, Agatha had been primed with a rich imagination and a flair for the dramatic. Certainly her creative imagination was helped along by her family’s love of the theatre, as Agatha herself attests: “One of the great joys in life was the local theater. We were all lovers of the theater in my family. Madge and Monty went practically every week and usually I was allowed to accompany them. As I grew older, it became more and more frequent.” Agatha would also attend the theatre when she visited her beloved Grannie in Ealing, “at least once a week, sometimes twice. We went to all the musical comedies, and she used to buy me the score afterwards. Those scores – how I enjoyed playing them!”

Family outings included seeing plays like “Hearts Are Trumps, a roaring melodrama of the worst type. There was a villain in it, the wicked woman was called Lady Winifred, and there was a beautiful girl who had been done out of a fortune. Revolvers were fired, and I dimly remember the last scene, when a young man hanging by a rope from the Alps cut the rope and died heroically to save either the girl he loved or the man whom the girl he loved loved.”

These theatrical expeditions weren’t merely passing entertainments to enjoy and forget. Agatha would spend time after seeing a show “going through the story point by point” and placing the characters on a homemade spectrum of good and evil based on her father’s love of card-playing. “‘I suppose’, I said, that the really bad ones were spades . . . and the ones who weren’t quite so bad were clubs. I think perhaps Lady Winifred was a club – because she repented – and so did the man who cut the rope on the mountain. And the diamonds –‘ I reflected. ‘Just worldly’, I said, in my Victorian tone of disapproval.”

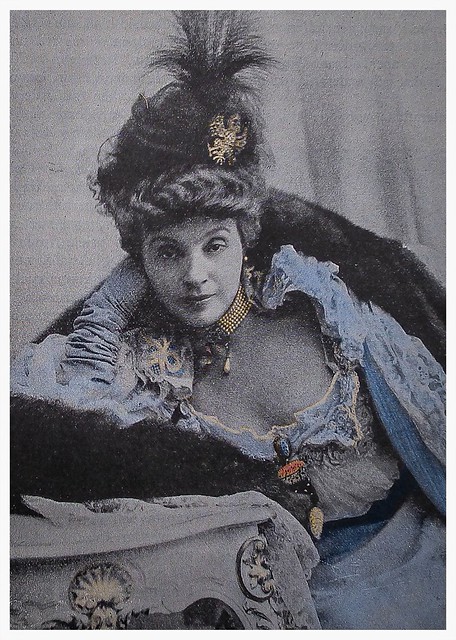

When her mother sent her to finishing school in Paris, Agatha would visit the Comédie Française, where she had the good fortune to see famed actresses like Sarah Bernhardt and Gabrielle Réjane perform. “(Réjane) had a wonderful power of making you reel, behind a hard, repressed manner: the existence of a tide of feeling and emotion which she would never allow to come out into the open. I can still hear her now, as I sit quiet a minute or two with my eyes closed, her voice, and see her face in the last words of the play, ‘Pour sauver ma fille, j’ai tué ma mère’ (‘To save my daughter, I killed my mother.’), and the deep thrill this sent through one, as the curtain came down.”

Modern fans often limit their perceptions of Christie to the shy, heavyset elderly women of whom they’ve seen pictures or heard stories from contemporaries. Young Agatha loved to play the piano and sing, and attending the theatre inspired her to craft her own dramatic experiences, like The Bluebeard of Happiness, which she put together at Cockington Court, the home of family friends, the Mallocks, around 1910. Gillian Gill writes of how Christie became “the star of amateur dramatics and musical events at home and at country house weekends; she indefatigably costumes, made up tunes, lyrics, and even whole operas, sang the lead soprano roles, and accompanied other people superbly at the piano.” This was Agatha at her most youthful and beautiful, surrounded not by the imaginary friends of her imaginary schoolhouse anymore, but by a coterie of other lovely young women who would become her real friends.

Clearly her love of theatre had an effect on her early self-training as a writer, for, along with poems and stories, she wrote plays. The first, The Conqueror, written when Agatha was about nineteen, is subtitled “A Fantasy” and is described by Julius Green as “a parable with a mythological flavor . . . the whole thing is rather baffling and appears to be some sort of morality tale.” It was never published or performed; neither were Teddy Bear or the horribly titled comedy Eugenia and Eugenics, or in fact a number of one-act and full-length plays. The tendency toward moralizing was corrected by Eden Phillpott when Agatha let him read her first attempt at a novel, Snow Upon the Desert. The lack of success at playwriting slowly reversed itself as well, beginning in 1930 with Black Coffee. But Gill points out that Christie’s flair for the dramatic followed her into her novel-writing career as well, where she “was known to develop her plots in dramatic scenes that she ‘talked’ to herself out loud.”

It makes sense that this method helped imbue Agatha’s stories with a sense of the theatrical. Certainly, her fantasies of the Gun Man and the Elder Sister, as well as her experiences seeing all forms of theatre, from the divine performances of Bernhardt and Réjane to the lurid pleasures of Hearts Are Trumps, contributed to the dramatic elements found in her books. And that is what we will look at next: first, the prevalence of actors found in her stories, comprising suspects, victims and murderers, and then a deep look at the way seemingly average characters used the skillset of actors – wearing disguises and immersing themselves in faked personas – to accomplish their murderous goals.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Christie, Agatha, An Autobiography, 1977, Dodd Mead, and Company.

Gill, Gillian, Agatha Christie, The Woman and Her Mysteries, The Free Press, 1990.

Green, Julius, Agatha Christie, A Life in the Theatre, Harper Collins, 2015.

Thompson, Laura, Agatha Christie, A Mysterious Life, Pegasus Books, 2018.

Worsley, Lucy, Agatha Christie, An Elusive Woman, Pegasus Crime, 2022.

Yes! This will be a great book.

LikeLiked by 1 person