- “’Chief,’ (Della) said, ‘why don’t you do like the other lawyers do?’

- “’You mean plant evidence, and suborn perjury?’

- “’No, I don’t mean that. I mean, why don’t you sit in your office and wait until the cases come to you? Let the police go out and work up the case, and then you walk into court and try and punch holes in it. Why do you always have to go out on the firing line and get mixed up in the case itself?’

- “(Mason) grinned at her. ‘I’m hanged if I know,’ he said, ‘except that it’s the way I’m built. That’s all. Lots of times you can keep a jury from convicting a person because they haven’t been proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. I don’t like that kind of a verdict. I like to establish conclusively that a person is innocent. I like to play with facts. I have a mania for jumping into the middle of a situation, trying to size it up ahead of the police, and being the first one to guess what actually happened.’

- “’And then to protect someone who is helpless,’ she said.

- “’Oh, sure,’ he said, ‘that’s part of the game.’”

The 1930’s incarnation of Perry Mason is as much action hero as attorney, and when you combine his restless drive with the cavalcade of calamitous women he meets on our “Girls! Girls! Girls!” tour, the trouble never lets up! That’s certainly how it feels in 1934’s The Case of the Lucky Legs. Where there was only one taloned vixen in The Case of the Velvet Claws and a single moody heiress in The Case of the Sulky Girl, this time out, Mason is beset by pretty dames with beautiful legs – although they don’t prove to be as lucky as the title suggests. The main attraction is Marjorie Clune who, despite her misguided decision to lie to her attorney, is the most loveable innocent we’ve met so far.

I wish the same could be said for Perry himself. It’s fascinating to see how Erle Stanley Gardner spent these early days formulating his main character. We know he’s beefy and strong, that he’s a fighter (he describes himself thusly at least fifty times here), that common legal work bores him, that he withholds expression until it’s necessary, and that his efforts on behalf of his clients veers toward the unscrupulous. In Velvet Claws, he seemed like an action hero. In Sulky Girl, he more resembled an armchair detective.

Here, he’s just a jerk.

Perry keeps his worshipful secretary Della Street in the dark for most of the novel. He finds the body (as he does in maybe sixty out of eighty-two cases) and then messes with the crime scene. He lies to private detective Paul Drake and sets himup to find the body, then “cheats” on Paul by hiring a second detective agency. He persuades an innocent girl to strip down and climb into a hotel bed, pretending to be his mistress, and then instructs her to chew gum and come on to the hotel porter. (Oh, it’s all for a good cause!) He drags more than one cab driver around the city and makes them wait for him indefinitely – he even tasks one with hiding evidence in a train station. Then he does the same thing with an airline pilot! Yes, it’s in service to justice for his client, but you can understand why Della keeps making all these maternal clucking sounds!

But what is this case involving lucky legs? It seems that a shady promoter named Frank Patton has a crazy scheme going, made all the crazier because it keeps working. He enters small California towns, meets the chamber of commerce and promises the merchants that he can put their town on the map and turn a fortunate young lady into a movie star if all the businessmen put their faith in him. And they do: a contest is held to find “the Girl with the Lucky Legs,” and the winner will have said gams insured for two million dollars (a decade before Betty Grable had her legs insured in a massive Hollywood publicity stunt) and be sent to a Los Angeles film studio with a three-picture deal.

That’s when everything goes wrong for the mark! The winner is sent to Hollywood, but a carefully worded detail in the contract always gives the studio an out, leaving the girl with zip and the chamber of commerce with zilch, while Frank drives off into the sunset with oodles of dough! The latest victim is the aforementioned Marjorie Clune of Cloverdale, who hightailed it to L.A. to become a star and has disappeared. Margy isn’t actually Mason’s client, though. That would be J.R. Bradbury, a “substantial citizen” of Cloverdale, who wants Mason to locate Frank Patton and bring him to his knees, thus rescuing Margy, whom Bradbury plans to marry.

It has probably not escaped the attorney’s attention that Bradbury, at 42, is nearly twice as old as the woman of his dreams. Plus, as Mason will soon discover, there’s another man, a handsome young dentist, who is looking for Marjorie, too. Mason takes the case and sets P.I. Paul Drake off to find Patton. Knowing that proof of intent to commit fraud is extremely difficult to make, Perry is itching to confront the con man and shake a confession out of him:

“I want to force him to betray himself; to admit that the whole thing is a racket; that his intent from start to finish is to defraud the merchants with whom he is doing business and the girl who is given the phony picture contract. In order to do that, we’ve got to crash in and surprise him. We’ve got to get him off his guard and rush him off his feet before he gets a chance to figure just how much of our talk is bluff and how much of it we can prove.”

Such a scene would be a glorious sight to behold; thus, it’s disappointing, if not surprising, that once Perry locates Frank Patton, he is as dead as dead can be, sprawled on the floor in his apartment with a knife wound bubbling away on his left breast. What’s more, the neighbor across the hall heard arguing just a short while earlier between Patton and some woman who was screaming about her “lucky legs.” And Mason, while fleeing the scene, runs right into a pretty young woman with bright blue eyes who answers to the name of Marjorie.

If the girl with the lucky legs didn’t do it, who did? The suspect list is minuscule and consists of another female victim of Patton’s con job, the hot young dentist who loves Margy, and Mason’s own client, Mr. Bradbury. I don’t like spoiling things, but the solution here would never work on the TV show. Even worse, it necessitates Mason never setting foot in a courtroom. Ultimately, the plot here is pretty spartan and the whodunnit aspects won’t thrill anybody, although there is one nice legitimate clue that leads straight to the killer. The bulk of the scenes take place in various hotel rooms, and there is one nice moment when Mason tracks down a hostile suspect who tries to scare him off by picking up the phone and dialing her hotshot lawyer – someone named Perry Mason!

The main reason to read The Case of the Lucky Legs is to check out our hero in his nascent stages, when his behavior was anything but respectable. Erle Stanley Gardner seems to believe the same thing: my copy of the book is a 1961 paperback reissue, and its chief asset is a short introduction by the author himself to the pleasures of reading early Perry Mason adventures.

Yes, Gardner reminds us, “Perry Mason shares the prerogative of all good fictional characters. They never grow old.” But as those of us who adore the fictional attorney can well testify, early Mason was a different animal to the more settled practitioner of law popularized by Raymond Burr in the hit TV show of the 50’s and 60’s. Gardner tells us that “nowadays, when the celebrated Perry Mason dashes past a cornerstone of legal ethics without bothering to touch base, bar associations shiver with apprehension.” But in those halcyon days when Mason was an ambitious yet far-from-famous attorney, “. . . a bunch of skeleton keys in his pocket was standard equipment. After all, who dared to keep a locked door between a Perry Mason reader and the mystery on the other side? Certainly not the author!”

The Case of the Lucky Legs is distinctive for breaking the cardinal rule of the canon (ROT-13: Znfba’f pyvrag vf arire thvygl!) and for being one of the few titles with two screen adaptations (more on that below). I’ve read better entries in the series, but it’s fun to watch our favorite attorney going through growing pains, and in a long-running book series that tends to follow a strict pattern set by the plot wheel, a broken rule is a broken rule!!

* * * * *

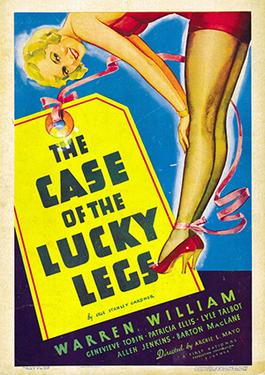

The Case of the Lucky Legs was Warner Brothers’ third outing in its Perry Mason series. Warren William continues his run as the first screen Mason, with Genevieve Tobin as the latest in a long series of Della Streets and Allen Jenkins, a member of the Warner Brothers Character Actor Brigade, as “Spudsy” Drake, the hen-pecked stooge who aids Mason in his investigations.

Frankly, this film made me tired! In its depictions of our main trio, in its pace and its score, it plays as a comedy. The suspects are played straight, at least, and the plotline more or less follows the book. But the “humor” wears me out, and William’s version of Mason as a lush and a joker, whose doctor puts him on a teetotaler’s diet of milk, who can’t remember his client’s name, and whose repartee with Della and “Spudsy” verges on the Marx Brothers, is not my cup of tea. At least the murderer is played by an actor who, a year earlier, had taken on the role of the killer in a much more famous mystery film from another studio, but their role is seriously curtailed from the part they play in the book.

“The Case of the Lucky Legs” was also a part of the Perry Mason TV series, premiering on December 19, 1959, as the tenth episode of the third season. It follows the basic plotline of the novel, with these exceptions:

- Cloverdale is in Utah (which makes sense)

- Two minor characters are given major motives and the killer’s motive is different

- There IS a trial, which comprises half the episode, prosecuted by Hamilton Burger with his stalwart investigator, Lieutenant Tragg, by his side (neither character existed in 1934)

The problem is that everything that makes the novel distinctive – Mason’s law-breaking stunts, his client’s increasingly belligerent behavior – are missing from the teleplay. What keeps it from being totally bland is the excellent casting of Jeanne Cooper (The Young and the Restless’ Kay Chancellor) as Thelma Bell, and Doreen Lang (who played the terrified Mother in the Diner in The Birds) as the nosy neighbor.

Next month: Our theme finally starts to heat up with an excellent adventure where Mason finds himself up all night solving the problems of a sleepwalker’s niece!

I’ve never read the book, but the 1935 film version is likewise too silly for me. I personally like the level of jocularity in the film version of Curious Bride, but this one goes too far for me.

LikeLike

Pingback: THE ERLE STANLEY GARDNER INDEX | Ah Sweet Mystery!