When I saw that Rich Westwood was celebrating all things mysterious from 1930 all month at his blog, Past Offenses, I quickly checked out the literary scene at the time. Folks, this year was golden! Nearly every member of the Detection Club seemed to churn one out that year, and some of them created landmarks with the novel they published: Agatha Christie debuted Miss Marple in novel form! Dashiell Hammett had begun serializing The Maltese Falcon the previous year, but it all came to a head in 1930. And perhaps, most notably for readers of Golden Age mysteries, a young Pennsylvanian made his debut, a lover of Poe with one foot firmly planted in the history and literary style of Europe, a man whose fascination with magic and the impossible would soon earn him the title of the Grand Master of the locked room mystery.

Yup, I’m talking about John Dickson Carr, the guy who invented Gideon Fell and Sir Henry Merrivale; the man who came up with nearly every variation on the impossible crime and inspired countless others to give it the old college try; the man who set the bar high for radio mystery programs, including writing most of the early scripts for the classic series Suspense.

In addition to his mastery of the locked room and all its variations, I consider Carr one of the four best handlers of misdirection, the other three being Christie, Ellery Queen, and Christianna Brand. (Is it any surprise that this lover of misdirection has just named his four favorite mystery authors?) As far as Carr goes, I was fairly selective, reading all of the Gideon Fell novels, but skipping the rest (except for The Burning Court – a classic!) I am slowly making my way through the Sir Henry Merrivale titles written under the pen name Carter Dickson. But before either of these portly gentlemen graced the pages of mystery fiction, there was Bencolin.

Henri Bencolin, the juge d’instruction of the Paris police force, appeared in early short stories by Carr and as the sleuth in the first four novels the author wrote. He reappeared once more in 1938’s The Four False Weapons and then, as far as I can tell, disappeared forever more.

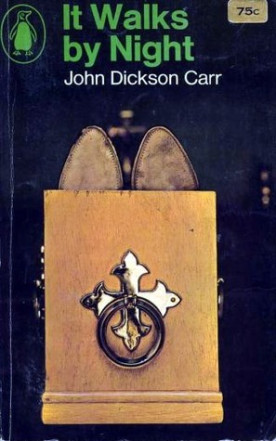

1930’s It Walks By Night introduces us to Bencolin and to Carr himself. As in many early Carr novels, an earnest young gentleman narrates It Walks by Night. Jeff Marle has come over from America to Paris and has looked up an old friend of his father’s, one Henri Bencolin. Bencolin promises to look after Jeff, yet I can’t say that I would place much faith in a man if he put my son through the events to which Bencolin subjects Jeff. They go to a torrid club where gambling and intrigue mask even more lurid crimes, and there they get involved in the murder of a young Duc, who has the ill fortune of being decapitated on his wedding night. Of course, his body is found in a room, the entrances of which were watched at all times, and nobody went in or out.

The investigation proceeds, and more deaths occur or are uncovered, each more gruesome than the last. Bencolin, who claims at the start that he knows the truth to every case almost immediately, leads Jeff and his team on a storm-tossed ride before he unmasks a surprising killer.

Now, debut novels are tricky to review or analyze. An author is clearly just beginning to establish himself, not only as a plotter but in the way he sets a tone for things to come. Each book, by necessity, either gets stronger as one begins to master the tricks of the writing trade, or the writing falls into a dull sameness and the author fades deservedly into obscurity. I can say that this was in many ways an auspicious beginning. It certainly grabs your attention and shakes you over and over until it tosses you exhausted in a pile on the floor. Yet I wasn’t sure that I really liked it. I had to talk to somebody else! And there’s nobody I would rather talk about Carr with than one of the blogosphere’s staunchest fans of the author, Monsieur JJ from The Invisible Event, who has graciously agreed to discuss the novel and the author with me.

JJ, thanks so much for joining me today. Let’s plunge right in: What do you see in this debut that begins to establish Carr as the author he would become at the pinnacle of his success?

Atmosphere, atmosphere, atmosphere. If we’re calling Carr’s peak the 1940s (and they were), he was at a stage then where the dropping of a single adjective could completely change the comportment of a scene or the response it incited in you. Here, he’s guilty of somewhat over-writing to ensure he gets his point across, but even then there are some beautifully descriptive and succinct expressions — ‘Surprising how a match-flame can blind one against a darkness moving and breaking like whorls of foam on water!’ has always stuck with me, especially given the context of that match. It’s Carr’s atmosphere that brings me back time and again — the plots are absolute marvels, but marry them to lifeless settings and you’re getting nowhere — and you see the very nascent threads of that here.

I was blown away by the graphic violence found in this novel! Each murder was more gruesome than the last! It reminded me of those old Tales from the Crypt comic books! Care to comment?

Part of me sees this as the natural extension of it being so over-written, the almost grand guignol aspect of how hideous it all is. No-one will get that alarmed over a stolen book of stamps, but horrible, violent, foul, repulsive murder…well, that’s something to stir the (ahem) blood. It brings home how unusual a thing it is, in spite of those of us who immerse ourselves in this kind of book on a regular basis: the ending of someone’s life in this way is a ghastly thing, and should be written in a ghastly way.

It’s interesting how some Golden Age writers wrote in a style meant to lull us into believing that this whole event – the murder (or series of murders), the suspects, the clues, the grand reveal – all could exist in a reality much like ours. Indeed, in his biography of Carr, The Man Who Explained Miracles, Doug Greene explains that Carr consciously wrote in an unrealistic style, although he certainly tamed the flow of adjectives as he matured. Greene says of this novel, “We don’t investigate the crime; we are fooled by it. Our attention is directed toward the supernatural, toward the innocent characters, toward everyone and everything except the true solution until Carr, and Bencolin, are ready to reveal it.”

How do you yourself rate the quality of the plot? (I have to admit that I guessed the killer because one early piece of misdirection seemed to stand out to me – I wouldn’t put this in the post but it’s when Mme. De Saligny says that she saw her husband walking into the card room and everyone caught a glimpse of someone who could have been the Duc.)

There’s not so much plot as there are “events around what’s going on” to my mind. There’s a huge amount of ancillary material that can be disregarded, once you look back at it. Let’s not claim Carr cracked the perfect puzzle plot at his first swing — he had to wait until The Problem of the Green Capsule for that — even the impossible angle of IWbN is kinda weak when you come to explore it. So I’m not disagreeing with Doug Greene. He still hasn’t talked to me after the last time . . .

Ha ha! We’ll save that juicy story for another day . . . Anyway, you, Greene, and I agree that IWbN is overwritten. I freely admit that I prefer Carr’s novels that find more of a balance between the supernatural and modern domestic British life, books like He Who Whispers and The Crooked Hinge. Where do you stand in your preferences, if you have any?

I agree, but I also think The Crooked Hinge has the same problem — as does The Plague Court Murders, and Hag’s Nook, and . . . well, many others. I don’t know if I have an overall preference in the type of Carr, but I’m more of a fan of Fell than I am of H.M, and there are many moments in Fell’s books where he’s described as watching someone very intently and it always gets the hairs on the back of my neck going. If Carr ever wrote a book where Fell sat in a corner and just stared at people, I’d probably read it every month for the rest of my life.

I agree with you in my preference of Fell over H.M., but neither one is in evidence yet. In 1930, Agatha Christie introduced Miss Marple in novel form (Murder at the Vicarage), the perfect sleuth for a traditional village mystery. Carr gives us Bencolin. He certainly fits with the aura of horror that drips from each page here. I have to say, though, that he kind of drives me crazy! How do you rate Bencolin among Carr’s sleuths?

Carr himself tried to backtrack on Bencolin come The Four False Weapons, having the character much more relaxed and even (I’m pretty sure) apologizing for or excusing his attitude in the earlier books. I like his abrasiveness — he was intended as a sort of anti-gentleman sleuth, with no smooth corners — and I sort of wish Carr had maintained that. But since we never really know him, I can’t lament the absence of more books featuring him. Carr got what he needed out of Henri and moved on. That’s great. I’d rather he ditched Bencolin and brought Fell to life than we never get Fell and have 35 Bencolin novels.

One year earlier, Ellery Queen made his debut. I know you just reviewed The Roman Hat Mystery and are about to do the same with Queen’s second novel, 1930’s The French Powder Mystery. So here are two Americans, peers if you will, and they are completely different in influence and style. Why did Carr make it to your top four Kings of Crime writing and Queen did not?

Urf. At a fundamental level, they did the same thing: produced superlative puzzle plots that can be held up as shining examples of the genre, dazzled readers with their ingenuity time and again, operated across several different mediums, and undoubtedly changed the lexicon and direction of detective fiction in the 20th century. So why Carr ahead of Queen? Carr was a far superior writer in my eyes, produced more legitimately stone-cold classics than Dannay and Lee (again, personal opinion and coverage key factors here), and seemed to be having a lot more fun while doing it. Those early Queens are hard work, man — I had to quit on French Powder because, crikey, wasn’t it ever a drag — whereas Carr had a quick start and just always seemed to be enjoying himself so much, never simply grinding them out to prove how smart he was even if they were a chore to trudge through. I’d pick a Carr novel ahead of any Queen novel to convince someone to give the genre a go, and he seemed more interested in the writing than the brand (witness the countless Queens not written by who we mean when we say “Ellery Queen”). But I know you’re not happy about it, and I’m sorry. Will you please stop prank calling me now?

Oh, dear, I seem to have made you uncomfortable . . . . . good! But I’ll grant you that some of those early Queens are damn near impossible to re-crack while no Carr novel has ever stopped me cold. Maybe it’s because Queen was influenced by Van Dine, who is very hard to read today, while Carr was influenced by Edgar Allan Poe. Still, his literary heart was mostly rooted in Europe, where he lived for many years. Both in setting and in tone, his writing was less realistic, more fantastical, like a Grimm’s fairy tale with none of the original nastiness excised for children. Is this part of Carr’s appeal for you, or does his style ever distract you?

I read Carr for the style, for that moment when a tennis court becomes a lethal place, or a flesh and blood man is snatched out of a sealed, guarded room. The supernatural aspect never really plays into it for me — the Grimms were big on the supernatural, of course, but Carr’s use of it is (almost) exclusively to dispel it with a rationale hewn from something more ingenious than you realised possible in the circumstances. It’s the way his brilliance for exploiting every situation is always ticking away that I find most compelling about Carr, and naturally the style of his writing — the way he chooses to present it — is a massive part of that.

A fascinating fact I learned in Greene’s book is that Carr’s “masterpiece”, The Three Coffins, (which I admit I’m not terribly fond of), was originally intended to mark the return of Bencolin under the title Vampire Tower. And it’s true that TTC is jammed with atmosphere, much like IWbN, more than the usual Dr. Fell novel (and minus the usual allotment of humor). I understand that Carr became disenchanted with his first sleuth, calling him “unreal . . lifeless . . . a dummy!” But do you think that Dr. Fell fits any better into this story?

I did not know that! It would have been an interesting fit for Bencolin…but I suppose it’s a question of which Bencolin: the apologist version of Four False Weapons wouldn’t quite have worked, the horror of it all would have overwhelmed him, I feel. That driven, heedless, arrogant man of Carr’s first works would have met the challenge full-on and probably also been crushed beneath its wheels. It’s undoubtedly a most Fellian case at it stands, I can think of no better detective in fiction to have taken it on — it needs the reassuring presence of a man who can pick up a few books in the study where a murderer has just vanished across a field of unmarked now three storeys down and quietly deduce the entire history of the victim of said killer from just a few notes in the front of the volumes. The magnificence of Fell is how secure you feel in his presence, and he is absolutely the rock around which the waves of that case break.

I want to thank my very special guest, JJ, for volunteering time out of his busy life to answer my questions and offer his insights on Carr and much more. (JJ, I will wire you the location of your car keys and your dog, as I promised, as soon as I post this.) And thanks to everyone who’s reading this for joining us on this exploration into the origins of one of the greats! I’d love to hear about your experiences with John Dickson Carr in the comments below!

Nice choices here! Carr was so good at that ‘impossible-but-not-really-impossible’ mystery, wasn’t he? And I’m so glad you mentioned The French Powder Mystery. What a great look at the early department store!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And such interesting mannequins, eh, Margot? 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂

LikeLike

I recently read for the first time Carr’s novella-length first pass at this novel, >Grand Guignol, published in what appears to be a student mag in 1929 (and available online at the Internet Archive), and really quite enjoyed it. Yes to the overwriting — no prizes for guessing, had you not known the publishing context, that this was a young man’s work. But it was easy to forgive this because there was so much vivid stuff in there amongst the floridity. It’s well worth a look if you get the chance, and, at maybe 25-30,000 words, it’s a quick read..

LikeLike

That is great news! Thanks for letting me know. I will definitely check it out!

LikeLike

It’s been a long time since I read it, but I’m no fan of It Walks by Night. I hate Bencolin and am so glad that JDC ditched him. Of course, since it’s JDC’s first book, one makes allowances. As mentioned, EQ’s Roman Hat Mystery is no picnic, either. Few hit a home run their first time at bat.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just to put this on record, when I first read It Walks By Night and The Roman Hat Mystery, back in the early 1970s, I very much enjoyed them both. I revisited them individually maybe a decade or two later, and still enjoyed them (and have Roman Hat on my current reread list). So could we please not have it, as it were, written in stone that these are bad books? They’re books that you didn’t enjoy.

LikeLike

I don’t really see my discussion of It Walks by Night as a pan, and I especially wanted to bring JJ into the discussion to provide a perspective on the promise this first novel held. I think my opinion of Bencolin, while indeed my own, was presented as such. And I think the fact that Carr quickly abandoned him suggests at least that as a sleuth he was problematical.

As for The Roman Hat Mystery, I do think it’s a dull book and that Ellery is at his most insufferable. But I haven’t even reviewed this book on my blog. JJ and I were merely discussing a shared opinion during our conversation. I strongly feel that Carr’s debut is superior, but I love both authors equally and consider them quite distinct from each other.

LikeLike

I was replying not to you or JJ but to J.J. McC.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And, I should add, I recently read Van Dine’s The Benson Murder Case, and both my desk and my forehead have the bruises to prove it — the cats learned to scuttle fat beneath the furniture. I think I can probably survive a reread of The Roman Hat Mystery. 🙂

LikeLike

You guessed it: “fat” = “fast.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with you about Queen’s first book (or two), but I think Christie’s first fared better. A little heavy perhaps, like a high tea at a middling hotel, but basically very satisfying.

LikeLike

Well, if you can enjoy either one of those books, good for you. I envy you.

LikeLike

Realthog, my cats are capable of scuttling fat!!!

LikeLike

This is going to sound like a silly theory but surely Vampire Tower would make more sense as the working title for He Who Whispers, given the vampire and the tower there…

LikeLike

Great post you two. Been wondering what had happened to JJ. I enjoyed this one on the whole and I found Bencolin an interesting sleuth and I actually liked that he was not larger than life, like Fell is. You can tell this is a debut novel with its referencing of other texts and I think Carr lets slip the identity of the killer through a too obvious literary allusion.

LikeLike

Pingback: ‘A full account of how to make a jam omelette’: The #1930book round-up | Past Offences: Classic crime, thrillers and mystery book reviews

Pingback: #150: The House That Kills (1932) by Noel Vindry [trans. John Pugmire 2015] | The Invisible Event

Great review, I like the interview style. It would be cool to see a few more done like this. I really love your line “I read Carr for the style, for that moment when a tennis court becomes a lethal place.” Well put.

I have very fond memories of It Walks By Night. I was fairly surprised that it was so well written, although in retrospect I don’t know why I assumed a first book would be amateurish. Carr certainly did grow as an author and I’m getting the sense that he first hit his full stride with Hag’s Nook.

To me, IWbN is all about the ending. I still remember the exact moment I read the solution. First, a rush of disappointment. Then a quick flip to the front of the book to check the map. Then, staring out into space for what must have been five minutes as it slowly dawned on me how audaciously simple it was. The conflicting sense of disappointment and profound enjoyment was such a unique experience. Within 10 minutes I was fully convinced this was one of Carr’s best solutions.

LikeLike

For some reason, as soon as the murderer said something in the early pages, I figured they were misdirecting Bencolin, and I had the killer down. What I did NOT have down was the identity of the victim, and I thought that was cool and the discovery of the last body appropriately ghoulish! The whole book is very sexual and grisly, quite surprising for the time period to me.

LikeLike

Pingback: IT’S SHORTS WEATHER: Perusing Bodies From the Library 3 | ahsweetmysteryblog

Pingback: My Book Notes: It Walks by Night, 1930 (Henri Bencolin, #1) by John Dickson Carr – A Crime is Afoot

Pingback: Oh #$%&! Not Another Blogger’s Tenth Anniversary!! | Ah Sweet Mystery!