It has been a pleasure hosting the Tuesday Night Bloggers during February’s exploration of Love (and Murder) in Bloom. Here are the months’ previous posts:

This week, Kate at Cross Examining Crime assesses the degree of success with which Dorothy L. Sayers combined murder and romance between her ace detective, Lord Peter Wimsey and his lady love, Harriet Vane.

And Moira at Clothes in Books discusses two examples of obsessive love leading to murder in Agatha Christie.

So is it just a coincidence that this week it was only the girls and I blogging about romance? Where was JJ? Where was Rich? Is love too “icky” a subject for some down to earth male perspective? Inquiring minds want to know . . .

And the thing is: I have no real concept of this male/female thing myself. It’s not how I roll. So as you may imagine – if you ever stopped to imagine such things – it was difficult for a boy like me to find mysteries, or any book or film for that matter, that contained positive depictions of people with whom I began to realize I shared an affinity. The few representations of gay culture that I did find were not exactly affirming. Basically, you had a choice between being an object of fun, an object of ridicule, a tragic figure, or a lunatic. Is it any wonder that I embraced being the class clown until, oh, I turned thirty?

We all grow up, and if we’re lucky, we learn not to base anything on the narrow prescriptions of a finite period of cultural history. (It helps when you have amazing and supportive families and friends. Living in the San Francisco Bay Area doesn’t hurt, either.) Today, I can look at the historical depictions of homosexuality from a more dispassionate distance. Every disenfranchised minority either learns to do that, or they don’t read old books or watch old movies.

It helps to have a brilliant new compendium of essays like the one historian and author Curtis Evans has just published: Murder in the Closet: Essays on Queer Clues in Crime Fiction Before Stonewall. Full disclosure: while I have never met Mr. Evans, he was one of the first members of the “Golden Age Detection” group on Facebook with whom I became acquainted and was kind enough to “guest star” me a couple of times on his blog, The Passing Tramp, when I was fit to bursting with opinions about Agatha Christie. I credit Curtis with inspiring me to start my own blog, even though he never told me to (so don’t go blaming him for this place!) I was excited when he announced last year that he was putting this collection together, and I can’t think of a better forum than this month’s TNB topic on which to offer my opinion.

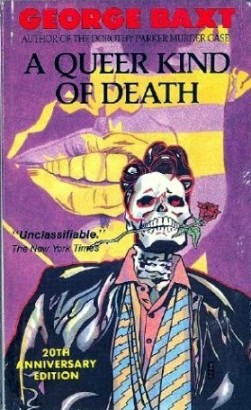

Evans has assembled sixteen contributors who, along with himself, offer twenty-three essays full of insights on the varied depiction of “queer aspects of crime fiction published between the late Victorian period and the height of the Swinging Sixties,” from the writings of Fergus Hume, author of The Mystery of a Hansom Cab, to the work of Joseph Hansen, creator of the tough but sensitive P.I., Dave Brandstetter, and George Baxt and his black hep cat, Pharoah Love. Both Brandstetter and Love are openly gay, and they embrace their sexuality in a way that you weren’t likely to find in the British country homes of the 1930’s. And so the collection manages to parallel the rise and fall of the Golden Age of Detection with the transformative history of gay culture up to just before the Stonewall Riots gave birth to the LGBTQ civil rights movement. Along the way, we meet authors who were themselves gay, although they could not and or would not be open about it. And of course, the masters of GAD, like Agatha Christie, are well-represented: mostly heterosexual writers whose writing manifested a wide range of understanding and opinion about what it meant to be queer. It gives vent to the opinion that, even in a time when the overwhelming emphasis of a mystery was the puzzle, an author might, even unconsciously, provide a cogent social commentary of the times in which (s)he lived.

I would be crazy to attempt a brief summary of the wealth of literary and social criticism being offered here. Evans provides a fine introduction at the start that puts what follows into historical perspective. One of the most important reminders he gives us is of “the confining strictures under which (Golden Age) crime writers once labored.” As my TNB colleagues have intimated throughout this month, the very notion of any sort of sexuality was often thought to conflict with the primary purpose of detective fiction: the presentation and solving of a crime. Authors were discouraged from including any distractions from the main event, and this included focus on heterosexual love affairs as much as any other. The fact is that a great many of the hundreds of writers who penned classic detective fiction were queer themselves and cheerfully acquiesced to follow the rules laid down for what constituted “serious” crime fiction, either as a shield to protect their “true” identities or as a subversive way of coding the truth about their lives for readers who shared their proclivities.

An author like Agatha Christie might include characters who were gay or lesbian, but, as noted Christie scholar John Curran reminds us in his essay, “’Queer in Some Ways’: Gay Characters in the Fiction of Agatha Christie,” every aspect of her books, including character and setting, was put there to serve her primary function of misdirecting readers. Still, Christie’s portraits of gay men probably make most modern-thinking folk squirm. Interestingly, her portraits of lesbians are, for the most part, more humane and life-like, as we see in A Murder Is Announced. And we must be grateful to Christie that only two of her gay characters turned out to be killers!

Because attitudes toward gay people in the early 20th century were so proscriptive, people who identified as queer expended extraordinary amounts of energy keeping their true natures a secret, avoiding the clichéd image of the lisping, effeminate man or butch woman, and often passing as straight – even to the point of marrying and producing childrenIn his wonderful essay, “Dropping Hairpins in Golden Age Detective Fiction: Man Haters, Green Carnations and Gunsels,” fellow blogger Noah Stewart offers this premise for a discussion of the varied “coded” characters whom enlightened folks could identify:

“And so the process of discerning homosexual characters in Golden Age detective fiction is weirdly similar to the process of discerning homosexuals themselves at that time. you will never be told that someone is a homosexual in so many words, although you may hear a character spoken of pejoratively as a “Miss Nancy” or a “man-hater by another. Instead, the way to understand what you are being told about a character is to make small but telling observations about their dress, habits, speech patterns and lifestyle in general.”

I remember the surprise I felt years ago when I was informed that Wilmer, the gunsel who worked for Caspar Gutman, the large yet effete villain in The Maltese Falcon, was actually his lover, and that the term “gunsel” itself referred to a certain type of homosexual tough guy. Mr. Stewart provides a deeper history of the term and the character, (who knew that it all goes back to Yiddish?), along with other character types of the Golden Age, including “prissies and sissies,” “man-haters” and “vampires.”

Last year, one of my favorite reads was Josephine Tey’s marvelous novel Miss Pym Disposes, set in that bastion of rampant lesbianism, an all-women’s college. I jest here, but my friend and fellow TNB’er, Moira Redmond of Clothes in Books offers a wonderful analysis in her essay, “Mutually Devoted: Female Relationships in Josephine Tey’s Miss Pym Disposes” to dispel this very myth that other critics have erroneously attached to the book. In fact, Moira explains, the community that Tey invents here is:

“. . . unexpectedly feminist. Tey has removed the male world of the time, and the girls are able to embed themselves in female friendship (or more, female careers, and even crimes of passion, without distraction. Only a female institution of the kind she describes would allow this to be explored at the time.”

I heartily concur with the conclusions Moira draws here, and the ultimate tragedy is that, in a secluded world where women, young and old, find a balm from the stresses put upon them in their relationships with other women, that Miss Pym, the “great” psychologist, could be so mistaken in her reading of these relationships, and that she could then blithely remove herself from the community without fixing the disastrous consequences she has wrought with her meddling. It’s a shattering ending and a beautiful book, and Moira argues that Tey is smart enough not to muddle the situation with a more explicit rendering of sexuality.

Curtis himself provides several essays, including one about the “various pseudonymous incarnations” of one of my favorite authors, Patrick Quentin (aka Q. Patrick or Jonathan Stagge), who was actually a partnership between real-life lovers Richard Webb and Hugh Wheeler. I was familiar with Wheeler because of his various projects with composer Stephen Sondheim (including A Little Night Music), so it was exciting to read up on Wheeler’s contributions with Webb to GAD fiction. Curtis focuses on one Q. Patrick title that I am actually afraid to read due to its excessive violence, but The Grindle Nightmare provides a smart analysis of the novel’s gay subtext that makes me want to seek it out.

Another of his essays allowed me to relive the pleasures I took long ago from reading the trio of mysteries Gore Vidal penned under the pseudonym Edgar Box. I dimly remember them now as quite witty and wicked. Here, the author analyzes each novel in light of our understanding of Vidal’s struggle with certain elements of his own sexual identity, specifically how to be both gay and “all man.”

Although many of the early instances of homosexuality in classic detective fiction are expectedly grim, there are pockets of enlightenment to be found, and in the second half of the collection, we see more characters like Dave Brandstetter and Pharoah Love emerge, wearing their sexuality openly and with pride. Brandstetter is a sensitive romantic with an active sex life to offset the brutal world of insurance investigation, while Love possesses enough sass and sexual energy to lead a Gay Freedom parade right down Market Street or 5th Avenue. In sum, this varied analysis of early queer history, as filtered through the lens of classic mystery fiction, should be lauded for its scholarly merit and compulsive readability. But more than that, Curtis Evans has assembled a book that packs a huge emotional punch for those of us who love mysteries but have long had to peer beneath the surface to find characters and stories with whom we can identify and empathize.

That’s a great TNC post and a just a great post Brad – and not just because I contributed to the book and you give me a lovely shoutout! The book is fascinating, I’m really enjoying reading others’ chapters, and the whole project is thought-provoking and beautifully done by Curt. And it’s always good to be reminded that we have made progress.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Moira. I’ve been jumping around in my reading, but I think there IS a cumulative effect to reading the essays chronologically. I keep hearing that old cigarette commercial in my head: “You’ve come a long way, baby . . . “

LikeLike

I shied away from this TNB topic largely because — with the exception of every Bright Young Thing romance in every GAD novel ever, and the marriage of the Beresfords — I could think of nothing to say, and I figured saying nothing is better than saying something dull week after week (people may argue that this doesn’t seem to hold me back the rest of the time…). And an investigation into the portrayal of homosexual characters requires he sort of grand oversight that this type of endeavour can provide, rather than me going “Er, there’s Hinchcliffe and Murgatroyd…” and then coming up short. This sounds like a great collection of essays on a very interesting topic, will be interesting to see the examples and studies cited, thanks for bringing it to my attention!

LikeLike

. . . and you can’t go wrong with Hinchcliffe and Murgatroyd! 🙂

LikeLike

But there’s great speculation about whether Hinchcliffe or Murgatroyd are truly lesbians considering Agatha Christie doesn’t go into full overt detail, but she couldn’t do that considering the time period she wrote, compared to now where a writer can go all out. But I prefer the speculation and the question of Hinch and Murgatroyd — are they or not? The outward physical stereotypes seem to spell out clearly that they are and on top of that, they are living together but if you look at the time period and the living arrangements of that time; it’s after WWII and many of the same sex lived together due to living costs.

If Christie wrote A Murder Is Announced today, do you think she would write in more overt signs of Hinch and Murgatroyd’s sexuality?

LikeLiked by 1 person

P.D. James had many same sex couples, mostly female, populating her novels, and she was quite open and wonderfully non-judgmental about their relationships. Frankly, I think Hinch and Murgatroyd were as far as Christie would have felt comfortable going. It says something that they are the most loving couple in the novel, and it’s just as nice that the community accepts them as that they are there!

LikeLike

I’m glad that people like you are buying the book, Brad. I thought for sure it would appeal only to libraries and gay studies professors. There’s a wealth of information on mystery writers and their work even I am unfamiliar with. Thanks for the publicity for what I think is an important work in the history of crime fiction. Moira, is right, Curt did an outstanding job with this project. I’m proud to say that I was a part of it, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

John, did you write the Tey piece? If that’s you, I’m just looking at your proposed collection about Christie and war! Very cool idea!

LikeLike

No, I’m J F Norris not J C Bernthal. His first name is James, I think. I wrote the essay on The Secret of Lonesome Cove by Samuel Hopkins Adams, another on the detective novels of Beverley Nichols, and a third piece is on the Pharaoh Love mysteries by George Baxt.

LikeLike

I’m honored, John! I think the most frustrating thing about this blogosphere is that we all don’t really know each other, and it can get confusing when I want to call someone by his or her name. I enjoyed your contributions very much. I have never read George Baxt, and a local used bookstore has several titles, like Swing Low, Sweet Harriet and Topsy and Evil. What do you recommend for a first go?

LikeLike

You really have to read the Pharaoh Love books in order because they are chronologically intertwined. The second book tells the ending of the first and the third has such an insane ending that it can only be fully appreciated after having the previous two books.

You’re an old movie fan, I think. You’d like his Hollywood mysteries featuring people like Tallulah Bankhead, Greta Garbo and Alfred Hitchcock as main characters. The detective is a Hollywood private eye whose clients tend to be movie people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

All those initials can get confusing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

So glad the book reached you that way, Brad, that’s great to know. I think the book recovers a lot of “closeted” history in mystery fiction. I want to thank the contributors for making this a special book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

John, the Hollywood novels look so familiar, I’m sure I read one or two of them a long time ago!

LikeLike

Hi Brad — Thanks for a great overview and exploration of this collection of essays. I’m excited to get a copy of the book, and happy to see that Curt, John, Moira, and others from the GAD blog community have contributed (or, in Curt’s case, acted as catalyst and editor). Looking forward particularly to reading the essay on lesbian themes in Gladys Mitchell’s work, although getting to know more about the output of George Baxt, Hugh Wheeler, Gore Vidal, and others is also intriguing.

Hope you are well — Jason

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for asking, Jason! I’m working my way through a cold, drat it! I am the worst sick person in the world, but I am keeping my fingers crossed that I’m at the tail end of it. Thankfully, there are stacks and stacks – and stacks – of books to keep me company! 🙂 I hope you are well, too!

LikeLike

Sorry to hear you’re under the weather! This whole winter season appears to be one long snuffle-and-sneeze epidemic. (I work on a campus, so am fairly attuned to the legion of Kleenex carriers and raspy throat coughers roaming the building. I’ve been able to dodge that bacterial/viral bullet so far…)

I don’t recall a murder mystery that takes place where multiple characters are suffering from a cold, but that might be interesting. Or maybe the detective could be the sufferer. There is a crime film where a cold plays an important part: The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, at least the original version with Walter Matthau does. And — can’t resist mentioning this to a Christie completist — one of my favorite (in terms of most ingenious) motives of all time involves an illness, in The Mirror Crack’d.

Feel better, and be wary of fans asking for autographs —

Jason

LikeLike