Christmas is just around the corner (he said two days before Thanksgiving!), and that means movie studios are about to inundate the theatres with their “prestige” films, hoping these will receive consideration for the big awards (the Golden Globes, the Oscars, and the Independent Spirit). Every year, this period where good movies are released shrinks because, let’s face it, they earn far less than those made during the rest of the year for Hollywood’s actual target audience —- fifteen-year-old boys.

Didn’t you know? When producers worry about box office revenues, most of us are de trop. Marvel Comics is now a bigger movie machine than Paramount or Universal. It didn’t used to be this way: when studios churned out ten to twenty times as many films per year as they do now, the industry was geared to grown-ups (with plenty to spare for the kiddies.) Of course, this occurred about the same time as the Golden Age of Detection, when mysteries were better, too.

November through December is still the time when the trenchant dramas, the noble histories, the high-brow comedies and the latest pictures by Spielberg and his ilk arrive. These dominate our attention for a minute, then again at the Oscars in the spring, and then most of them fade into obscurity because – let’s face it – we go to the movies to have fun, not to think, right, people?

I myself like to do both, and sometimes a genre picture comes along that allows me just that. It offers me a whale of a good time and it gives me pause about the human condition. Sad to say, although this sort of picture may do well at the box office, it seldom gets the attention of the Motion Picture Academy.

Let’s look at four of my favorite movie genres: horror (when it doesn’t opt for cheap tricks by bathing itself in gore), musicals, mysteries, and science fiction. Of these, only musicals have fared pretty well in winning the Oscar award for best picture. Out of ninety winners in the history of the Academy Awards, nine were musicals. I want to point out, however, that the last winner, Chicago, occurred in 2002, and that was the first time a musical had won in thirty-four years. Who can say if a recent hit like La La Land will revive the genre, although a promising sign is the arrival this season of The Greatest Showman, a musical about P.T. Barnum, starring Hugh Jackman and with a score by La La Land composers Benj Pasek and Justin Paul.

As for the other three genres . . . well, forget about it! Rebecca (1940), In the Heat of the Night (1967), and The Silence of the Lambs (1991) just about do it for mysteries, although Silence contains just as many of the tropes of a horror film. Otherwise, horror and sci-fi are batting zero. And it’s too bad because the American reliance on genre to bring in the bucks while it lavishes praise and awards on something like 1% of its film output smacks of outright snobbery. I’m not here arguing that we should equate box office winners with quality. What I’m asking for is some consideration for genre films that do their category proud by making us laugh, scream, cry . . . and think.

With that, I offer four titles chronologically – a musical, a mystery, a science fiction film and a horror movie – that you should see not only because they all push the right genre buttons, but because their creators have found a way to simultaneously entertain and enlighten us in brilliant ways. All of these movies were box office successes, as befits a well-made genre film. In addition, they offer such an insightful mirror on the prevalent human condition of their time that each of them deserves to be considered not merely as models of their genre, but as great films in general.

THE MUSICAL

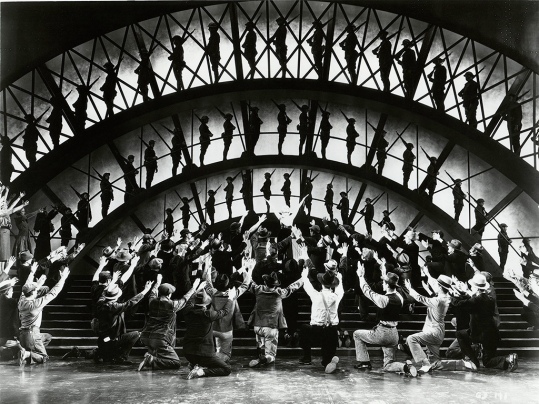

1933 was a stellar year for movie-making, largely because the Hayes Production Code had not yet gone into effect. This freed films to show life as it is, as well as expose and examine its every dirty seam. That’s exactly what the studios did. From the sly sexual farces that Paramount turned out, like She Done Him Wrong and I’m No Angel (both starring Mae West and Cary Grant) or Design for Living (a sophisticated take on a ménage a trois) to the slam-bang gangster movies and musicals at Warners, film audiences had full access to hard-hitting and wildly entertaining films. At Warner Brothers’ the musicals dazzled as long as choreographer Busby Berkeley held sway, with his complex geometrical dances and chorus lines filled with hundreds of beautiful, scantily clad girls. No less than three Berkeley films came out in ‘33: 42nd Street may be the most famous, and Footlight Parade has James Cagney hoofing it up to give it class. But my favorite of the trio is Golddiggers of 1933, which stands out from the rest for its incisive depiction of life at the height of the Depression.

Both 42nd Street and Footlight Parade center around male protagonists. The first is the ultimate backstage musical as it follows producer Julian Marsh (Warner Baxter), who must stave off bad press and mortality itself by staging “Pretty Lady,” his greatest musical ever. In Footlight Parade, Chester Kent (Cagney) must battle against progress: the growing movie industry itself is killing musical theatre! Kent’s solution is to create musical “prologues” for the movies themselves, although it is clear that none of these numbers would ever fit on a stage!

Like the others, Golddiggers is a backstage musical, but not only is it female-centered, it’s proletariat-centered. Its tale of four chorus girls trying to survive in these troubled times, where financial troubles could shut down a potential hit days before it opens, is hilarious throughout yet openly confronts the terror that working stiffs go through every day. The direction (by Mervyn LeRoy) is killer, and the company of actors delivers the sparkling, double entendre-filled dialogue with zest. Aline MacMahon, Ruby Keeler, Joan Blondell and Ginger Rogers make a wonderfully varied bunch who set out to prove that no Depression – and no man – will ever get the better of them.

Being Pre-Code, the film dealt frankly with sexual matters: while three of the girls have the title of “golddigger” thrust upon them by rumor, prejudice, and happenstance, one of them (MacMahon) embraces her role as a woman out to capture and seduce a wealthy man. Not only does she win in the end, she and her mate are divinely happy! All the men are relegated to love interests for the women, and most of the guys turn out to be fools for love.

But it’s in the songs and dances that Golddiggers reveals to the audience the mores and fears of a generation. The movie starts with a close-up of Ginger Rogers leading a line of chorines all dressed in gaudy coin outfits. “We’re in the Money,” she sings, and the bright scenery and undulating bodies try to prove it. But before the number ends, the doors burst open and men rush forward to repossess every prop and stick of furniture, even ripping the costumes off the girls’ bodies. The Depression has gunned down yet another Broadway opening.

It doesn’t take long before new opportunities arise, and the girls face new challenges with resilience and humor. Berkeley’s two production numbers in the middle of the film showcase the sexiness and the glamour of these girls and more. “The Shadow Waltz” is a Berkeley classic, elegant with its neon-lit violins and kaleidoscopic patterns, while “Pettin’ in the Park” is a lewd commentary on the loose morals of modern women, with the men shouting “Hallelujah” at the fact. Yet the number ends proving the girls are in control of their virtue and that they expect a deeper commitment from their guys before they are willing to be “carried away”.

Four minutes before the end of the movie, it looks like the requisite happy ending is in sight: the production company has withstood all obstacles and made it to opening night, and every chorus girl has found her guy. Yet if the opening of Golddiggers of 1933 reminded us in an ironically amusing way that no matter how much you can try to escape the Depression in the movies, it’s still out there, then the finale delivers a musical gut punch which obviates all the romantic folderol that preceded it.

“My Forgotten Man” is a masterpiece that would fit right in with the tragic musical operas of the 1970’s and beyond, like Rent and Les Miserables. It uses song (a rousing chorus of the blues), movement and spectacle to make a plea for those who suffer just outside the theatre doors, specifically returning soldiers, many of them suffering from PTSD, whose lives have been obliterated by economic ruin. This is a torch song for the masses, and Joan Blondell and singer Etta Moten give the song’s melodrama such dignity that you can’t help but be moved in ways you might not have expected . . . from a mere musical!

THE MYSTERY

Make no mistake: Rear Window (1954) works perfectly well as an entertainment, and if you wish to leave it at that, so be it. You can check off all its assets:

- one of the greatest Hollywood leading men of all time (James Stewart)

- one of the classiest, most beautiful actresses (Grace Kelly)

- a supporting cast like no other, even without famous names (although Thelma Ritter delivers the best comic supporting performance of all time, and Raymond Burr is a sheer delight as the antagonist)

- a plot (and script) that is funny, suspenseful, romantic and scary, all in one

- the trademark brilliant direction of Alfred Hitchcock

The result is a delectable crime film that delivers in every way a good mystery should. We could leave it there and move on. But then, you are here reading an eclectic blog by a mystery nerd, so I figure you’re willing to dig a little deeper with me. While Vertigo gets on all the best movie lists for its dark vision of obsession, Rear Window is just as dark, but it is leavened with great wit and a suspiciously happy ending, so it is not taken as seriously as Vertigo. Make no mistake at dismissing Hitchcock’s depiction of the urban human condition during a sweltering summer in the 1950’s. After thirty years of making movies that celebrate the power of love, Hitchcock’s message takes a dark turn here that will continue for the rest of his career: love is difficult, and real happy endings are elusive.

“It Had To Be Murder,” the short story by Cornell Woolrich that was the basis for the film, is a snappy little noir piece about a guy, bored from sitting in his apartment with a broken leg, who watches his neighbors and becomes increasingly certain that one of them has murdered his wife. The tale hit all Hitchcock’s buttons, and he crafted a script – or, rather, played Svengali to screenwriter John Michael Hayes – that used Woolrich’s plot as the skeleton upon which to explore his favorite motifs: the persecution of an innocent man, the importance of love and marriage, and the powerful and sick allure of voyeurism.

But here Hitchcock twists his own themes. The hero of the film should be the innocent man on the run, in the exact position that Robert Donat finds himself in The Thirty Nine Steps, or Robert Cummings in Saboteur, or Cary Grant in North by Northwest. Instead, our “hero” is the persecutor of that man: Stewart’s L.B. Jeffries has no proof that Lars Thorwald has committed murder, but he wants him to be guilty because . . . well, that would make the game of tracking him down more exciting!

Early on, Hitchcock imbues his main character with a character flaw, a penchant for voyeurism. Knowing that the audience will no doubt identify with James Stewart, the director quickly points out that we share this perverse trait with our hero, as stated openly by Jeff’s nurse, Stella (the mordantly funny Thelma Ritter): “We’ve become a race of peeping Toms,” she warns, and she means those of us seeking thrills in the movie theatre, too!

Every Hitchcock hero has a beautiful blonde helpmate, a woman initially suspicious of the man’s innocence who transforms into his champion and eventually his lover and wife. Grace Kelly’s Lisa operates from different motives: she already loves Jeff, but she can’t get him to commit to her romantically. She only assists Jeff in proving Thorwald’s guilt because crime-solving is the thing that binds them together. The danger Lisa puts herself in for Jeff is like an audition to prove to Jeff that she can stand beside him for the adventurous life he craves. She passes the test, yet at the end we see her put aside an explorer’s biography and take up a fashion magazine, indicating that the differences between them haven’t really disappeared. Can their love overcome their differences? Will this marriage survive? It’s the first time in a Hitchcock film that the romantic fate of a couple is left ambiguous.

Up until now, Hitchcock had utilized the hunted man’s journey to prove his innocence as a trial by which the hero could graduate from his bachelor life – or worse, a dependence on his mother! – and become a willing partner in the sacrament of marriage. In Rear Window, the director doesn’t abandon this theme, but he suggests that marital bliss is all but impossible to sustain. He does this by populating his film with a fascinating assortment of neighbors for Jeff to spy on, from the newlyweds, whose feverish coital pleasure slowly disintegrates into nagging and recriminations, to the sexy dancer who entertains businessmen while her soldier husband is overseas, to the comical couple who lavish all their love on their dog, to the tragic Miss Lonelyhearts, a middle-aged woman who entertains inappropriate – or invisible – strangers in her apartment.

These people, along with the Thorwalds, mirror Jeff’s relationship with Lisa, and it’s a troubled image. And yet, before you start thinking that Rear Window is a load of doom and gloom, Hitchcock provides hope through an exploration of another thematic preoccupation of his: voyeurism. In a customary display of irony, the director wanted audiences to flock to his films and make him a rich, famous man – he traded in thrills and chills for that very reason – but he also liked to remind us that, in sitting in a darkened theatre watching other people live their lives, we are all voyeurs getting our kicks out of other folks’ troubles. It’s a highly pleasurable pastime, but if we don’t get out and live, people, the greatest joy we can hope to find is of the vicarious variety.

Jeff takes pictures for a living, and he finds his thrills by shooting dangerous subjects in far-flung locales. (The implication here is that he broke his leg taking a picture of an auto race, and the wheel came off a driver’s car and hit him.) Comfort and luxury is anathema to him, an emasculating sign. When he is stuck in his apartment, he channels his adventurous spirit by snooping on his neighbors rather than deepening his relationship with Lisa. She, in turn, longs to pamper him with take-out lobster dinners and lovemaking until he is well. She is a model, the subject of other men’s assuredly prurient interest, and she lives the very pampered life Jeff reviles. It is a sore subject between them, and it threatens to tear them apart . . . until Mrs. Thorwald disappears.

Whatever her motives, Lisa joins in on the hunt to brand Thorwald a killer with an unbecoming rigor, climbing up fire escapes and stealing evidence. Her foolishness works, binding her to Jeff’s heart. (“Gosh, I’m proud of ya,” he swoons after she nearly gets herself killed.) Ultimately, though, Jeff is left alone to face his nemesis. He can no longer just watch; he has to act! Amusingly, Hitchcock makes Jeff pay a price for his voyeurism, but he does allow him to get the girl in the end. It will be the last time the director allows this to happen: with Vertigo and then Psycho, his voyeuristic “heroes” will pay for their watchfulness with a descent into madness. It’s what I love about Hitchcock: he crafts delectable thrillers that also illuminate both the darkest and the best natures of the human spirit.

THE SCIENCE FICTION FILM

Filmmakers have been using science fiction to reflect on the mores and fears of their own generation since movies began. The concept of technology enslaving mankind was seen as early as 1927 in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Sci-fi as metaphor reached its apotheosis in the 1950’s when films explored both the dangers of radiation posed by the atomic bomb (most of these resulted in the creation of a very large bug) and the worry engendered by the Communist scare (Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Invaders from Mars). And even though this genre is associated with massive amounts of CGI and special effects, a good science fiction movie doesn’t need to rely on spectacle to work.

I don’t want to come across as a snob here. I love big effects as much as the next guy. When aliens land, I want the spaceship to look cool and the aliens to dazzle. When I’m traveling in space, I want to believe I’m traveling in space. Still, bigger isn’t always better. A lot of the big spectacle science fiction tropes have been merged or subsumed into other genres, especially action and horror. (Last year’s Passengers created a hybrid of sci-fi and romantic comedy, to everyone’s horror.) The thoughtful science fiction film is becoming a rare bird today, but when it occurs, it is a wonder to behold. Every other year, we are bombarded by a new Transformers movie, but snuck in there are incredible films exploring the relationship between man and machine, films like Ex Machina and Chappie.

Last year, Arrival, a science fiction film, earned such acclaim that it was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture. It won a single award for Sound Editing, but it earned other awards that give more respect to genre filmmaking. Arrival is based on a 1998 short story by Ted Chiang called “Story of Your Life.” Amy Adams plays a linguist named Louise Banks who is summoned by the military when twelve alien spaceships arrive and hover above locations all over our planet. The U.S. joins every other country so honored in trying to figure out the aliens’ motive for coming to Earth by making contact and trying to communicate with these beings.

The aliens look a bit like walking octopi (although they are labeled “heptapods” for having only seven limbs), and they make sounds that Louise and her team cannot make much sense of. However, they have an intriguing written language that springs from ink emitted through their tentacles, and this proves more promising. As the American group makes further headway in deciphering the aliens’ message, so do the other nations in what seems to be a competition to be the first to communicate. And then an argument springs up over the meaning of a particular symbol: are the aliens offering the Earthlings a weapon?

The concept of interaction with aliens as a metaphor for our nations’ own problematic relations is nothing new. It was done perfectly in 1951 with The Day the Earth Stood Still. Arrival does explore this theme, but it has another layer to it that is even more powerful and surprising. It seems that the heptapods’ relationship with time is quite different from our own . . .

I won’t say any more about the plot. I do want to mention that I saw this film when it opened exactly four days after our last election. I was devastated by the results and worried about our future. Arrival took me out of that feeling for a couple of hours and while it didn’t provide me with a solution to our problems, it moved me very deeply. I felt a bit like Pandora, who had watched every evil pour out of the chest she had opened . . . only to be followed by the spirit of hope. I assure you that Arrival is not in any way as turgid and goopy as I just sounded. It’s a movie that will make you think about a lot of things.

THE HORROR MOVIE

I love a good legal drama, so a couple of weeks ago I took myself to see Marshall. This film chronicles a real life case taken on by Thurgood Marshall, the first black Justice of the Supreme Court, early in his career when he worked as a lawyer for the NAACP, traveling across the country to represent innocent black men who had been accused of crimes and couldn’t afford representation. I say “innocent” because it was the policy of the NAACP to only help innocent men it believed were victims of a system of “justice for all” that was rigged against African-Americans.

I have since done some research on the case of The State of Connecticut vs. Joseph Spell, and it appears that the film pretty much got the whole thing right. In 1940 Marshall is sent to Bridgeport to defend Spell, a chauffeur, who has been accused of raping and trying to kill his wealthy employer’s wife. But when Marshall steps into court, the judge allows him to be present only if he does not speak (Marshall didn’t have jurisdiction to practice law in Connecticut) and hands the case to the presenting attorney, a respected Jewish lawyer named Sam Friedman (no relation).

Like I said, the case is real, but I’m sorry to say the film disappointed me. I managed to predict every plot twist that occurred, which was odd since the whole story isn’t fiction. It felt like lazy storytelling, real life reduced to a by-the-numbers legal thriller about the put-upon good guy forcing the bad people to find justice for the underdog. I knew that the defendant had lied about something. I knew that the accuser had been attracted to her employee. I knew that the Jewish attorney would overcome his prejudice against the black lawyer and vice versa. I knew that the bigoted judge would be forced by his love for the law to overcome his prejudices and that the sneering district attorney would get his comeuppance. It’s a great story told in so-so fashion, but it looked great!

That reminded me of the 2016 film Race about Olympic medal winner Jesse Owens, an inspiring biography if there ever was one, yet it was somehow reduced by its fairly strict adherence to all the clichés of a sports movie: the gifted natural who falters then wins, the curmudgeonly coach, the racist teammates transformed by respect for Jesse’s ability. Yes, it probably all happened that way, but it got stuck in its genre rather than transcended it.

Now, I believe we should make a point of learning the stories of real life heroes from every culture and strata and highway and byway of our history, particularly in these troubling times when a small segment of small-minded men is trying to negate America’s rich status as a nation of immigrants. I also want my movie experiences to be fresh and exhilarating, not blandly familiar. Truth to tell, the people sitting next to me at Marshall were more than pleased with the film, and I saw an elderly woman crying as she related her memories of Marshall to her seatmate. So it clearly moved people, and I’m just a hyper-critical bastard who wants to really really learn more about what it’s like to walk in another man’s shoes. I got that last year watching Moonlight, which won the Oscar for Best Picture in a televised moment of upset that shouldn’t have been upsetting – it deserved to win! And I felt it the other evening as I watched a fabulous horror movie called Get Out.

Modern horror has become so heavily reliant on gore that I have all but given up on the genre. Truth to tell, that’s why I didn’t bother seeing Get Out when it premiered in theatres. Whenever a friend would say, “You have to see this movie!” I would ask them, “Is it gory?” And nobody ever said, “No, it’s fine.” So I’m here to tell any other squeamish horror lovers that if the gore level in this film is moderate enough for me, you can certainly handle it! It’s an original idea, expertly written and beautifully acted by a fine cast.

Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) is a gifted photographer with a cool apartment, a great dog and a beautiful girlfriend, Rose (Allison Williams). Despite his reluctance, he agrees to drive upstate to spend the weekend with Rose’s parents and brother. Chris’ reluctance stems from the knowledge that Rose hasn’t told her folks she is dating a black man, but the Armitage family seems welcoming. The Armitages are wealthy liberals who voted for Obama and are apologetic for their black maid and groundskeeper, who are, to say the least, a very odd couple. Dean (Bradley Whitford) is a neurosurgeon, and his wife Missy is a psychiatrist who offers to perform hypnotherapy on Chris to cure him of his smoking.

That’s all I’m going to say about the plot. From the moment Chris and Rose take off on their trip, director Jordan Peele begins to build an atmosphere that is increasingly unsettling. It’s also a funny film, but you find your laughs coming out almost as a little scream, as Chris begins to feel that all is not right with this world.

What he discovers delivers the scares of a horror movie as well as the punch of satire, this one on liberal do-gooders. In many ways, the movie functions as a mystery: what is going on here? The answer to that is surprising and satisfying, as is the series of climaxes that make up the film’s third act. Nowadays, horror movies all end in the same tiresome way: a battle between good and evil and a supposed resolution, followed by a surprise reversal at the credits. Reading about the making of Get Out, the director clearly toyed with options in this and other directions. I think the choice he made was the right one, and it ends up striking a blow against those who would look at the color of a person’s skin and imbue him, for any reason, with a sense of being “other.” By the end of Get Out, we stand with Chris and say, “Enough is enough.”

If you haven’t watched any or all of these movies, you have a treat in store for you when you do. Get Out is showing on HBO right now, and all the films are readily available on DVD. Having movies like this to savor is just one of many reasons to feel thankful.

Happy holiday, everyone!

No fair Brad, this is at least 4 posts rolled into 1 😀 Not seen ARRIVAL yet but agree completely otherwise. I think GOLDDIGGERS OF 1933 was the first musical I ever saw, about forty years ago ….

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, Sergio! I could be celebrating my 400th post if I cut these mammoth writings up! Yikes!

LikeLiked by 1 person

As you say, Happy Holiday. There is a lot to read through here, and your interesting take on these films. Hitchcock does have a brilliant way of taking the simplest of human traits and letting our imagination run wild in fear -but of what? It is the screen shots and the music that take effect on my emotions with a feeling of exaggeration focused on the irrational.

As before, Happy holiday.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree completely, Brad, about Rear Window. It’s a truly classic suspense story, isn’t it? And the timing, acting, and so on are superbly done, I think. An Arrival was really very good, too. I’m glad that it didn’t depend on the special effects for success; there’s a real story there, and it’s done quite well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And by not depending on the FX for success, Margot, the effects that they included felt more real to me; it was so easy to accept that this really could be happening.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hsven’t seen a single one of those films but very much enjoyed this appreciation of them. It’s a problem ‘genre’ seems to have in every format, a sort of assumption of shallowness which is by no means always correct. Any story can be used to illuminate humanity (and entertain you doing it).

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Assumption of shallowness . . .” What a great way of putting it! That’s part of it, as is an assumed reliance on formula. We watch coming attractions and feel we’ve seen that movie before. Some people LIKE this! These previews are made to assure viewers that they will get the movie they think they’re getting, right up to the end (which is often spoiled). It’s disheartening how many people don’t like to be surprised!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t seen Arrival – yet – but the short story it’s based on is one of the most powerful SF works I’ve ever read. I do have a hard time seeing how they’re going to translate that story into a film – I’m always wary they’ll take the path of least resistance and just focus on the visual cool stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Actually, while the spaceship and the aliens are well depicted, this is one of the most realistic Sci-fi films I’ve ever seen in its depiction of the event of an invasion. Most of us would see events unfold on TV screens, out of the corner of our eye, not with spaceships blasting over our head. This movie focuses on the effect all this has on the people involved.

LikeLike

To me, the short story “The Story of Your Life” is not about an alien invasion. I don’t recognise the description you’ve given above, Brad. This makes me yet warier.

Chang’s story is about how language affects the way we see things. Did they actually manage to transfer that to the big screen? If so, kudos to the film makers.

LikeLike

Linguistics and word meaning is a BIG part of the story. The world is brought to the brink of catastrophe because countries can’t agree on the interpretation of the alien language. (And even that sentence puts it too simply.) The story also deals with time, and that’s where it really grabbed my heart.)

LikeLike

Okay, it seems to be that the film plays up the alien invasion bit quite a lot. In the short story, the aliens are really only there to make sure that the language issue works.

But the main thing about the short story is simply about the scientist mother and her relationship with her daughter over time. Which I guess is the bit that grabbed you as well.

Did you read the short story too? It’s available on the ‘net, though I’m unsure about the legality of that… 🙂

LikeLike

I have NOT read the story, although I sure want to! And I honestly think the invasion aspect is NOT played up in the film. You really have to see it though to understand what I’m obviously having a hard time describing. It is one of the most thoughtful sci-fi films I have ever seen.

LikeLike

Oh, I’ll get around to seeing the movie one day. I’m sure it’s better than most other movies around, even though it probably won’t fulfil all of the promises of the short story. 🙂

And do try to find the written version, it’s a wonderful piece of SF. I added it to my own collection of mindblowing SF stories.

LikeLike

GET OUT is an amazing movie. Truly brilliant. I almost didn’t go because the trailer made it seem like a mash-up of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? and a slasher flick. Then I read a rave by someone who I trust implicitly so I did go expecting something exciting and fresh. And I wasn’t let down at all. GET OUT is all that and a helluva lot more. It turns out to be …dare I write this?… OK, I’ll do that thing I hate to do… [SPOILER ALERT] a revisionist Stepford Wives, only a lot more timely and powerful. [end SPOILER] I loved every minute of it. Everyone should see regardless of whether or not they like horror movies. It’s destined to become a cult classic just like the movie which served as its inspiration.

LikeLike