WARNING: This post attempts to analyze and reflect upon a work of detective fiction , and as such, certain plot points will be discussed, including the solution to the murders. If you have not read Crooked House yet, I hope you will join in after you have done so. (And really, you should read this book before the movie comes out!)

“Dispute not with her: she is lunatic” William Shakespeare, RICHARD III

Despite the fact that Golden Age detective fiction is enjoying a renaissance, and long forgotten authors have been excavated for our pleasure, it is the career writers, those who published across the decades, who are a mystery fan’s bread and butter. Some of them, like Gladys Mitchell, Rex Stout and Ngaio Marsh, may or may not have improved in their craft but seemed content to never vary their content or style. John Dickson Carr’s modernized his style and experimented a little with historical thrillers, but basically he remained the JDC of old until the bitter end. Finally, there were the authors, like Ellery Queen and Patrick Quentin, who divided their careers into significant periods and experimented often, with varying degrees of success.

Where, then, to place Agatha Christie? Of the group mentioned above, her career aligned most closely to Carr’s. She had her penchant for semi-political thrillers, but most of the time she turned out whodunits. And yet, there were some shifts in her timeline that are deserving of mention.

The nine novels she wrote in the 20’s constitute Agatha Christie’s training period, and on retrospect, it was a bumpy ride. That decade produced one genuine classic – The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), a fairly conventional village mystery even for its time, in every way except the finale. The rest ranged from entertaining mysteries (Styles, Murder on the Links) and thrillers (The Man in the Brown Suit, The Seven Dials Mystery) to some odd hokum (The Big Four) and stylish mediocrity (The Mystery of the Blue Train).

The 1930s were Christie’s Golden Age, the time when she hit her stride and produced seventeen mysteries, many of them full on classics of the genre. Among the best were Murder on the Orient Express, The A.B.C. Murders, Death on the Nile, and And Then There Were None, but there was virtually nary a lemon in the basket. (Even Dumb Witness has its charms!)

I love the 30’s, yet for me, Christie’s richest and most mature work appeared between 1940 and 1950. One could argue that the complexity of puzzle is missing in some of these cases – although I don’t think Christie ever truly cheated her readers there – and the fact that the crime-solving aspects were balanced against deeper characterization and a richer depiction of the social and historical background of wartime and post-war England may not have been everyone’s cuppa! Whether you prefer the Lee family of Hercule Poirot’s Christmas (1938) or the Angkatells of The Hollow (1946) is a matter of personal taste. Both clans accomplished the same purpose of providing a closed circle and enough drama to inspire murder; it is the presentation of these families that is so markedly different. The Lee sons can be reduced to: the dutiful one, the naughty one, the priggish one, and the angry mama’s boy. This categorization doesn’t work at all in The Hollow, but then The Hollow sacrifices some of the Golden Age trappings to present a fuller-bodied picture of an upper middle class family in the throes of crisis. Which you prefer is your call; I like ‘em both!

And then there is the Leonides family of Crooked House, Christie’s 49th mystery, published one year shy of her thirtieth anniversary as an author and one of her personal favorites, as she claims in the foreword:

“I don’t know what put the Leonides family into my head – they just came. Then, like Topsy, ‘they growed’. I feel that I myself was only their scribe.”

Crooked House was the work of an author at the height of her powers, but also a novel that, like many of her later titles, borrows and builds upon old ideas and tricks. It is one of those rare mysteries of hers that not only sets itself in a recognizable world, one dealing with the after effects of a real war and its lingering effect on the British people, but also makes this background integral to the actual mystery. The time is certainly ripe for an in-depth discussion for the novel that has been previously classified as “unfilmable” has finally made it to the screen. Already released in Italy to good reviews, it is set to premiere in the States on December 22. You can bet I’ll be there to let you know what I think. Meanwhile, there is so much to say about the novel, I hardly know where to begin.

Background

Think of it: from 1939 to 1945, Christie largely ignored World War II! Her only politically tinged novel of the period, One, Two, Buckle My Shoe (1940) finds Christie in her usual “silly thriller” mode, creating a picture of world politics far too lacking in real world references or details to be believable. Then there was N or M in 1941: a light-hearted Tommy and Tuppence romp about Nazi spies.. And then there was . . . nothing! Christie was fulfilling her contract to the British people, to take them out of themselves amidst the air raids and the bombing and the march of Hitler through the West and Hirohito in the East by creating charming microcosms of the world – villages and country houses and stylish London neighborhoods, even a farm in ancient Egypt – where evil is rooted out and order restored.

What, then, to make of the two post-War novels Christie published back to back in 1948-49? Taken at the Flood is a sprawling country-house family mystery (it sprawls because it comprises several households, stretching all the way to London), with an inheritance plot and a female heroine who, among other things, must choose between two romantic rivals, one safe, the other dangerous. We can talk at length at another time about all the interesting socio-political trappings of this novel: how the first death, the one that jumpstarts the story, occurs during a London blitz; how the heroine, Lynn Marchmont, is a returning Wren, how her “safe” fiancé bridles at the fact that he couldn’t go to war while his romantic rival is a returning war hero with all the attendant personality disorders that Christie’s soldiers tend to collect; how war affected the lives of upper class country families throughout Britain.

The most intriguing thing is that, although the mysteries contained herein are solved, the solution is far from traditional, and nobody can argue that order for the Cloade family is restored, most especially the future fortunes of Lynn Marchmont. Is the unsettling nature of Flood a fluke? Perhaps – until one considers the follow-up novel. Crooked House is even more traditional in its premise – a pure country house mystery – but much of the book is an odd juxtaposition of tradition and the subverting of those traditions. Some of the book feels rather mundane – the trope of an old man marrying a beautiful young wife, the business with the wills – yet it all leads to one of the most extraordinary solutions in the canon. Does this title achieve higher status simply because of its ending? Or is there more to this novel to account for its special notice? That is a question worth considering.

The Plot

Crooked House opens with the promise of hope and new beginnings after the lengthy conflict of World War II. I can only imagine the number of conversations that actually occurred between young men and women, just like Charles Hayward and Sophia Leonides, who having been thrown together by war ended up falling in love. Christie never dwells too long on physical attraction in her work. She describes Sophia as “refreshingly English,” and Charles announces with becoming reticence: “I liked what I saw.” He is also enamored of Sophia’s “clear mind and a dry sense of humor,” yet he is surprised one night by the realization that he wants to marry her. An engagement means waiting for at least two years, for Sophia is set to return to England, while Charles must remain on duty in the Egypt Foreign Office. Their conversation is practical, their reasons for sticking together more logical than romantic.

Before she leaves, Sophia gives Charles a hint of what he’ll find if he seeks her out upon his return: a large, extended family living together due to the exigencies of war “in a little crooked house . . . “ Characters quote that nursery rhyme so many times throughout the novel that the connection starts to feel forced, but there’s no denying that the house itself – the very structure – is crooked:

“It was incredible! I wondered why it had been called Three Gables. Eleven Gables would have been more apposite! The curious thing was that it had a strange air of being distorted – and I thought I knew why. It was the type, really of a cottage, it was a cottage swollen out of all proportion. It was like looking at a country cottage through a gigantic magnifying glass. The slant-wise beams, the half-timbering, the gables – it was a little crooked house that had grown like a mushroom in the night!”

Any good love story is fraught with complications. Of course, this being a murder mystery, Charles’ and Sophia’s path to happiness is blocked by the death of her beloved grandfather, Aristide. Once it is learned he died from poisoning, Sophia refuses to marry Charles until the case is solved. And by an extraordinary coincidence – really, this one is almost too much – Charles’ father is the Assistant Commissioner of Scotland Yard, and Charles has an in to becoming the “man on the scene” for the police and the nominal sleuth of the novel.

Yet, as a detective, Charles is pretty ineffectual. True, he is observant, and he shares his thoughts and feelings with his father, with Inspector Taverner who is in charge of the case, and with the reader. Ultimately, however, Charles is played for a fool all around: his first impressions of the people around him are nearly always incorrect, he nearly loses the girl through a flawed alliance with Brenda Leonides, “the enemy,” and he doesn’t actually solve the case. It isn’t until the final page that he asserts himself enough to claim his mate and take her away from the crooked house, which may or may not be the best thing for Sophia.

Thoughts on Being Crooked

The victim, Aristide Leonides, is frequently described as being “crooked,” and this appellation operates on several levels. His appearance is appropriately distorted: “Nothing much to look at. Just a gnome – ugly little fellow – but magnetic – women always fell for him.” More problematic to modern readers is the suggestion that being an immigrant from Greece who took advantage of every opportunity that came his way somehow makes Aristide crooked. He rose in business, although his businesses weren’t what you’d call classy – restaurants and catering, “second hand clothes trade, cheap jewelry stores, lots of things” – and he made money in everything he put his hand to.

In America, we call such a man an entrepreneur and admire his ability to raise his status. The suggestion that his behavior is crooked –here meaning “dishonest” – is, at best, tenuous, and is magnified by Aristides’ status as a foreigner: “Nothing he did was ever illegal – but as soon as he’d got on to it, you had to have a law about it, if you know what I mean.” Even more presumptuous was the fact that he married above his station, to a woman whose choice might have been as much about defiance as love: “There was something exotic and dynamic about him that appealed to her. She was bored stiff with her own kind.”

Nobody can deny that, more than anything, Leonides is smart! He bought real estate in Swinly Dean before it became posh. He made a fortune several times over, giving the money to his children and then starting over again. He was, in many ways, the antithesis of Simeon Lee, another “self-made man” from Hercule Poirot’s Christmas who earned his fortune largely by cheating others, who disparaged his late wife to an early grave, and who took absolute delight in tormenting his sons and their spouses. By contrast, Aristide was loyal to his wife, who bore him eight children and then died, loving, generous, and protective toward his family.

Perhaps he was too protective! Compare Aristide to Gordon Cloade, the late patriarch of Taken at the Flood, whose death during the Blitz sparks the family trials to come. Out of love, both men supported their families during the war, coming to their aid in any crisis, protecting them from the outside world. Upon their deaths, they each left behind a family of emotional cripples. In Crooked House, some profess a sense of freedom from Aristide’s benevolent tyranny: his second wife Brenda may or may not have a passion for the childrens’ tutor; his daughters-in-law, Magda and Clemency, long to escape the house and spread their wings. His grandson, Eustace, wants to run off to college; even eleven-year-old Josephine hopes at last to be able to take ballet lessons.

But others are more discomfited by Aristide’s death. His sons have unfinished business to deal with: Roger, the oldest, wants to make right the financial mess he has made of the family business before he flees with his wife to an island paradise, while Philip still resents his father’s presumed neglect. Sophia mourns the loss of her grandfather, perhaps because in terms of intellect she resembles him more than anybody else. And sister-in-law Edith DeHaviland either hated Aristide or loved him, depending upon whom you talk to.

The most interesting – and to my mind, problematic – use of the word “crooked” stems from Sophia’s refusal to marry Charles until the case is solved – and only if the “right person” is found guilty. That person is Brenda, the outsider. This would certainly be convenient for the family, causing the least amount of emotional fuss. But Sophia’s larger concern is this: should one of her immediately family members have committed murder, it would mean there is a strain of “crookedness,” of mental distortion, in the family blood.

Christie provides a houseful of suspects whose situation has invariably bred madness in fiction. There’s Philip, the neglected son, who broods about the past and his father’s lack of love for him, and Roger, the disappointing favorite, whose amiable nature masks insecurity and a terrible temper. Philip’s wife, the actress Magda West, is a horrific egoist. Roger’s wife Clemency is a cold scientist. Eustace has never been the same since his “illness.” People go around saying Josephine is “not right in the head.” And Lawrence Brown is “sensitive” – too sensitive to have fought in the war. Even elegant Aunt Edith, a paragon of upper class snobbery who looked down her nose at Aristide, is rumored to have actually been thwarted in her love for him. Many of these “types” have been unmasked as the killer in other Christie novels.

The only characters seemingly devoid of the “crooked” taint possess the most legitimate motives of all: Sophia inherits all the money, and Brenda loves another man. Christie does a fine job balancing these “ordinary motives” with an exploration into the strained passions of the other characters. In doing this, she adds depth to characters who otherwise run the risk of being stereotyped. For example, with each scene that she appears in, Clemency becomes more and more human . . . and ironically a more likely suspect. In contrast, Philip and Magda become more and more repellent, both as artists and as parents. Even Eustace has some strong moments, and teenage boys were Christie’s weakest character type, perhaps because she had little to no experience with them.

Lawrence Brown initially comes off as both an odd duck and a dull fellow. Sophia suggests that her grandfather actually arranged Brown’s presence in the house to give Brenda a romantic life he could not provide himself. He assumes – as probably most of Christie’s readers at the time did – that Lawrence’s standing as a conscientious objector made him a weak lover. And yet Christie ultimately reveals Brown to be both an excellent teacher and a man of strong moral character, as he explains his reasons for refusing the draft to Charles:

“All right then, what if I was – afraid? Afraid I’d make a mess of it. Afraid that when I had to pull a trigger –I mightn’t be able to bring myself to do it. How can you be sure it’s a Nazi you’re going to kill? It might be some decent lad– some village boy– with no political leanings, just called up for his country’s service. I believe war is wrong, do you understand? I believe it is wrong.”

Charles gathers all of this information, peeling back layers of character for the reader to savor, but he doesn’t quite know what to do with it. And there is certainly a suggestion that he simply doesn’t have the stuff to put the facts together into a reasonable solution. Josephine treats Charles as if he were an amiable idiot and goes about trying to solve the case herself. Sophia says she depends on Charles, but she grows increasingly distant from him – perhaps because he is sympathetic to Brenda’s plight as another outsider in the family. In the end, when Charles reports the name of the killer to his father, Sir Arthur says, “Yes. I’ve thought so for some time.” Even removed from the scene, Sir Arthur has remained several steps ahead of his son.

The Solution

Up until now, I have discussed the plot in detail but have tried not to reveal anything about the solution. I figured that anybody reading this has already read the book. But I know myself: somebody tells me not to look in the closet, and . . . So those who have not yet read Crooked House and have still followed me to this point for some ungodly reason need to stop here if you don’t want the ending ruined for you.

Try as she might, I rarely buy Christie’s forays into psychology, particularly her theories of insanity. Now, it’s true that this this may have been the prevailing idea at the time, that craziness is an inherited trait. Intermarriage amongst the upper classes certainly contributed to genetic weakness. And the existence of the hidden maniac befits the mystery author trying to hide certain things about her murderers until the end. In titles like Murder Is Easy, And Then There Were None, and Towards Zero, Christie informs us at the start that the murderer is a maniac. We learn certain facts about these killers in order to provide evidence of their insanity in the end. But the author ultimately presents these three as simply having been born “wrong,” and this idea seems, at best, convenient, and at worst, simply wrong.

So let’s acknowledge that the inherited taint of madness was a prevalent belief at the time. Doyle used it frequently. John Dickson Carr had plenty of characters who were the children of murderers and therefore more likely to commit murder themselves. Ellery Queen, in The Tragedy of Y, presents a family tainted by syphilis, but his subsequent foray into nutty clans, There Was an Old Woman, presupposes that one woman can have six children and that the trio begotten by Husband #1 can all be crazy, while those of Husband #2 are upright. It’s hard to swallow, but accept it we must in order to carry on in the GAD world.

Now, my friend Ben at The Green Capsule glommed onto the solution to Crooked House right away. I wonder if modern readers are more likely to do so after the types of fiction we have been bombarded with since 1949. But at the time of its publication, I can only imagine the open-mouthed reaction of Christie’s readers when Charles opens Josephine’s detective journal and reads the words: “Today I killed grandfather.”

The author goes to great lengths to prepare us. (I wonder if she thought she might get into some difficulties with her publishers and/or her public if she didn’t make sense of this nightmare.) Chapter Twelve is a marvelous tour de force, in its own minor way rather like Carr’s locked room lecture in The Three Coffins or Queen’s discourse about dying messages in The Tragedy of X. In his most endearing and human moment in the novel, Charles Hayward sits down with his father and rather helplessly asks, “Dad, what are murderers like?”

“The Old Man looked at me thoughtfully. We understood each other so well that he knew exactly what was in my mind when I put that question. And he answered it very seriously.

“’Yes,’ he said. ‘That’s important now – very important, for you . . . Murder’s come close to you. You can’t go on looking at it from the outside.’”

Classic mystery writers were long at pains to convince readers that anybody could be a murderer. Some books are crammed to the rafters with odious characters, but your average mystery should contain people we enjoy spending time with, and the unmasking of a such a person as the killer carries with it both the element of surprise and a certain emotional resonance. “I trusted this person.” “I liked this person.” “I can’t believe that this person was the murderer!” These are all reactions that a mystery writer hopes her reader will have (and it’s the reaction I myself always want to have.)

Sir Arthur reminds his son that murderers can be “nice ordinary fellows like you and me.” In his experience, the person who hates “to excess” is unlikely to kill; it’s the person full of affection who has that affection thwarted of the love and attention they crave. “I think people more often kill those they love than those they hate. Possibly because only the people you love can really make life unendurable to you.”

Sir Arthur also points out the common denominator for murderers he has known:

“I’ve never met a murderer who wasn’t vain . . . It’s their vanity that leads to their undoing, nine times out of ten. They may be frightened of being caught, but they can’t help strutting and boasting and usually they’re sure they’ve been far too clever to be caught.”

Christie creates a template for a killer who is both thwarted by love and incredibly vain – “strutting and boasting” as it were – and one character begins to emerge. The problem is – it’s a little girl, and little girls don’t do murders. It’s rather cheeky then of Christie, don’t you think, to put these words into Sir Arthur’s mouth halfway through the novel:

“A child, you know, translates desire into action without compunction. A child is angry with its kitten, says ‘I’ll kill you’, and hits it on the head with a hammer– and then breaks it’s heart because the kitten doesn’t come alive again! Lots of kids try to take a baby out of the pram and drown it, because it usurps attention – or interferes with their pleasures. They get– very early– to a stage when they know that that is wrong– that is, that it will be punished. Later, they get to feel that it is wrong. But some people, I suspect, remain morally immature. They continued to be aware that murder is wrong, but they do not feel it. I don’t think, in my experience, any murderer has really felt remorse . . .”

Josephine wants ballet lessons. Grandfather won’t give them to her. Grandfather must die. It’s as simple as that. Which, of course, makes the whole situation that much more horrible. But it’s not really that simple. Where were Philip and Magda when all this was going on? Locked in their own worlds, ignoring their children. Eustace hates his sister, and Sophia is overseas for two years. Brenda is frightened of the girl – she actually warns Charles early on that Josephine is mentally unstable – and Lawrence is distracted by Brenda. It’s up to the little girl to fend for herself, and she decides to take drastic action when she doesn’t get what she wants.

I imagine this would have had a far greater impact in 1949, given the relationship of the adult world to children and, perhaps, to British children especially. Aristide rushes to Roger’s defense, marries a seemingly pregnant waitress, and helps finance Magda’s rotten plays. But he dismisses Josephine, telling her she would not be a good enough ballet dancer so why bother? He fails to recognize that, next to Sophia, Josephine has inherited his will, hid determination to succeed against all odds. She has also inherited her mother’s vanity and her father’s dark nature.

Are pride, vanity and moodiness inheritable traits? Is there a physiological/genetic predisposition for sociopathy/psychopathy? That, my friends, is the question.

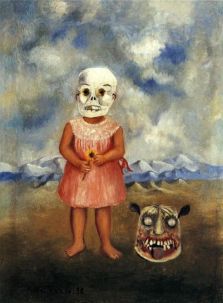

Six years after the publication of Crooked House, William Golding wrote Lord of the Flies, and William March wrote The Bad Seed. Golding’s book is brilliant literature about the breakdown of civilization through the actions of young schoolboys. It states that we are all savages, and that the thin veneer of civilization, of separating right and wrong, can be erased in a snap. The Bad Seed is pure camp about Rhoda Penmark, an eight-year-old psychopath. An immediate success as a novel, it was immediately adapted for the stage by Maxwell Anderson (and enjoyed a long, successful run on Broadway) and then, two years later was made into a film by Mervyn LeRoy (and received four Oscar nominations). The Bad Seed is not a whodunit: Christine Penmark realizes early on that her daughter is a cold-blooded killer. What’s more, Christine discovers that she herself was the biological daughter of a female serial killer, which means Rhoda’s mania is an inherited trait.

Watching The Bad Seed today will probably make you laugh, especially the movie. In the novel and play, evil wins out, but the movie had to adhere to the rules of the Hays code, so Rhoda is suitably punished for her multiple crimes. And in the end, just to remind us that it’s all a movie and all in good fun, the director stages a theatrical curtain call for all the actors – all of them alive now – and even has the mother figure pull Rhoda over her knee and spank her! (I’m serious!)

Still, the success of The Bad Seed was a harbinger for countless future books and films about evil children. Movies like Village of the Damned (1960), The Innocents (1961), the ’61 episode “It’s a Good Life” from the TV series The Twilight Zone and on and on to The Exorcist, The Omen, Rosemary’s Baby and Children of the Corn have made the evil kid a standard of thrillers and horror movies for the past 60 years. Until finally the time is right to put Crooked House on the screen . . . and wonder what its impact will be.

Agatha Christie didn’t start this trend. She was most certainly not the first mystery writer to create a murderous child. Yet, up to the revelation that Josephine has killed two people, Christie creates a startlingly effective portrait of a pathetic monster. Throughout the novel, we are bemused, annoyed, intrigued by Josephine’s efforts at detection, mostly because she is clearly a fan of Agatha Christie! She follows the tropes of classic GAD: the most likely suspect, the false arrest, the second murder. Part of us is on her side – yes! we say, that’s how these stories are supposed to go! Part of us wants to scream at her: Cut it out, you little fool! Do you want to get yourself killed? In the end, it turns out that Josephine, who has been busily writing in her little journal throughout the novel, resembles in some ways her creator, as she plots all the happenings at Swinly Dean. If only Josephine could have planned out her own finale! As it stands, the ending feels rushed to me: Edith’s sacrifice makes quick work of Josephine and leaves Charles free to put down the uneasy mantle of detective and whisk Sophia off to Persia. How Sophia will carry on her duties as the New Family Leader from afar is not explained, nor are we shown how the news of Josephine’s culpability affects the family. With claims that she is saving her grand-niece from suffering “if called to earthly account for what she has done.” But I wonder if Josephine would have suffered, or if she would have relished being in the spotlight. Why, she might have become more famous than Edith Thompson! Instead, Josephine dies, and the world goes on without her, forever oblivious to her achievements.

“Poor child . . . “

This is a great and interesting breakdown! I have been collecting vintage Agatha Christie’s over the past few years and although I have this book, I haven’t read it yet. Don’t worry! It won’t ruin anything for me, I still plan on reading it but now I can think back on what you took away from it and make some analyses of my own.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope you didn’t read my ending! It really pays to go into this one without knowing the solution! But thank you for your kind words. I hope that after you read it, we can talk about your reactions!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Alas, I did. But it’s okay, my goal is to read all her books so I’ll still read it and act surprised. Lol

LikeLike

Spoilers Do I even have to mark spoilers in a post like this? Well, it’s good habit anyway, I suppose.

I think you captured what clued me onto the killer perfectly midway through your post – Christie plainly describes the characteristics that the killer must have, and lo and behold, there’s a character who just happens to match that description to a T. I suppose decades ago you would automatically rule out the child, but in this day and age, the child is practically expected to be the killer. Of course, I probably watch more horror movies than I should…

I would love to use this space to comment on the new film adaptation, but as I’ve learned that you haven’t watched it yet, I’ll bide my time…

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m sorely tempted to go to iTunes . . . and yet I feel I want to watch this one in the theatre, surrounded by people who have no inkling as to what’s to come. Of course, this presupposes 1) that the movie will even go into wide release! (I mean, in England they’re showing it on TELEVISION!!!) and 2) that anyone else will be interested in seeing it! We’ll see . . . and then we’ll talk! 🙂

LikeLike

Give in to temptation!!!! Well, that’s a selfish request because I just can’t wait to nerd out about this one.

LikeLike

Fascinating discussion, Brad. I find it interesting the way writers of that time handled children’s psychology in general. On the one hand, they certainly aren’t/weren’t simply smaller adults. On the other, we didn’t have the tools we have now to understand their thinking. And you bring up the fascinating nature/nurture issue, too, which of course plays a role here. Christie touches on that more than once, and I find it interesting to see how she explores it.

LikeLike

Yeah, I tend not to buy the nature argument, Margot! In The Bad Seed, Rhoda is raised by kind, loving parents. Her mother is not even aware of her own biological connection to a killer. The idea that Rhoda got that “serial killer” gene passed down to her seems ridiculous to me. But then, I never took biology, so what do I know?!? 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is a really good discussion of one of Christie’s darkest books, and I’m looking forward to seeing the movie.

The idea of the SPOILER child murder SPOILER isn’t new with Christie; Conan Doyle and Ellery Queen were there before Christie – and Christie, I suspect, had Queen’s book in mind. The first British edition (Collins, 1949) blurb reads: “it was the old Greek himself who had supplied the blue-print for his own murder, actually suggesting the very method to be used – by the right person…” Which is a fair description of the plot of Queen’s novel. Christie’s is a weaker detective story (there aren’t many clues, and the detection is much weaker than in a Poirot, let alone Period I Queen), but the characterization is better, so the revelation of the murderer’s identity is more shocking. Part of the appeal of Christie, I believe, is her powers of characterization; her suspects are always believable people – and, as you say, seemingly /likeable/!

One sentence brought me up short, though: “Some of them, like Gladys Mitchell, Rex Stout and Ngaio Marsh, may or may not have improved in their craft but seemed content to never vary their content or style.” That may be true of Stout, but it’s simply not true of Mitchell, any more than it would be of, say, Margery Allingham.

Many of her books up to the early 1950s (the first quarter-century of her career!) are often bold experiments in style and form, and she was looked on as one of the most UNpredictable of detective writers. This is, after all, the same writer who told a couple of novels from the perspectives of children, another in the vein of Wodehouse, and has a fake diary in the style of M.R. James in another. Others will play with a particular genre (Greek drama, Mystery play, Buchanesque adventure novel, Gothic novel, bucolic farce, Metaphysical poetry…) The style of the late books is, again, quite different from that of the early books; they’re told more through dialogue than narrative, in the manner of I. Compton-Burnett.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I bow to your knowledge of Mitchell, Nick. My apologies.

I’m a little confused by your Queen reference, as “the old Greek” would suggest The Greek Coffin Mystery, and I know you mean another novel that I will not name here. In that book, the child who kills does so by following a dead man’s blueprint. What’s interesting is that this child is barely in the book and has almost no dialogue. Yes, the ending is shocking, but it doesn’t hold a candle to Christie’s version, even if it is chock full of clues!

I also know which Holmes story you mean. It is one of my favorites and one of the most moving stories in the canon.

LikeLike

Thanks for the extensive review. 🙂 I liked ‘Crooked House’, and I thought it was the superior work to ‘Tragedy of Y’. As a novel, I found ‘Tragedy of Y’ stilted, with somewhat weird characterisation – and, in this instance, weirdly unenjoyable. It was even more unfortunate that the ending was semi-spoilt for me, when I read a review making a comparison with ‘a certain Christie novel’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I felt the same way, John, although Y is a better novel than The Tragedy of X! But Queen got there first; so did Margerie Allingham (haven’t read her take on the idea).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just finished re-reading this in preparation for the upcoming movie release. I had a post planned around Christmas time. Supposedly the movie will be released in limited run on Dec 22. I expect it to show up in Chicago at the “art house” — Landmark Century Theater.

The “shocking” ending has been forever ingrained in my memory bank and so I paid close attention to the way Christie set out her clues and misled the reader. This is a textbook case of having *everything* handed to you on a platter. The first time I read this over forty years ago I said to myself: “Aha! I’ve got it. It’s Edith. It has to be Edith.” And that’s exactly what she wants us to think from the moment Edith grinds the bindweed under her feet during her first meeting with Charles in the garden. But did we pay close attention? To the lecture on dangerous children Sir Arthur delivers, to the tell tale dirt clumps on the chair in the guest house, Josephine’s oddly adult disdain for the police, among the many clearly stated points. I was marveling at how cleverly she leads the reader into first believing that Brenda and Laurence are killers and then switching our suspicions to Edith in the final scene.

I need to add another book to the shelf of surprise child killers of the Golden Age. There is a Q Patrick book with teenagers as the murderers published in the 1930s. I don’t think I should give the title though for those who have yet to read it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I know which book you’re referring to. I haven’t read it because of its very dark nature, including violence against animals. I did not know that the killers in it were teenagers. If I ever run across it, I might skip it!! 🙂

LikeLike

I hate this story. Too creepy

LikeLike

As I’m sure is now common knowledge, the movie will be shown on terrestrial TV here in the UK — I’m not sure whether this was achieved before the BBC’s planned Ordeal by Innocence was taken out of the schedules, but it probably was — and I’m veru curious to see how it transfers. I mean, I remember very little of the details, indeed my distinct memory is that of very little in the way of proper clues…but I was probably looking in the wrong direction the whole time (the end came as a complete surprise to me — it is sudden, I agree, but I think Christie wanted to just dump it on you and leave you reeling; I wouldn’t be surprised if in her ideal version of the book it was a final line reveal, but she felt the need to tidy up a few threads and so things got rather more drawn out).

I barely have time to read the books I haven’t read, never mind going back to reread ones I already have, so I’ll watch the film, remember every detail — I have a weirdly eidetic memory where moving pictures are involved — and will compare the two when I finish Christie and start rereading titles. Thuis, expect my full-blown analysis of film v. book in 2035. It’ll be worth it…

LikeLike

What a superb study of the book. For once I have actually read this one so can really appreciate your insights.

The notion of inherited insanity has definitely prevailed at many times in history, perhaps more in the UK than the US or here???…I’ve read lots of books which have variations on the theme. Even in the 60’s Ruth Rendell was writing strongly on this subject. In A NEW LEASE OF DEATH (1967) a father refuses his daughter permission to marry the man she loves because that man’s father has been convicted of murder. His actual words when asked why he won’t approve of the marriage, despite thinking the woman perfect in every other way, are “Heredity…I shall watch my grandchildren from their cradle. Waiting to see them drawn towards objects with sharp edges.”. I shudder at his thinking but I imagine it was (perhaps still is?) a commonly held view.

As for killer children…I think it’s still a difficult subject to depict well…as you say there is such temptation to go overboard with melodrama or gothic-style themes. Here I think Christie made it as ordinary as possible which is far more likely than inner monsters. A local author called Jane Jago wrote a modern take on this theme in a book called THE WRONG HAND which took as its starting point a case loosely based on a UK one in which 2 boys killed a toddler for no apparent reason. The book actually reminded me of the Christie in the way it ‘normalised’ the killing…trying to show that it’s not some kind of Exorcist-type invasion of a child’s soul that causes such things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The cruelty of children – and I remember this from my own childhood as well as witness it in my job – is chillingly banal in its origins. It takes a while for morality to “set,” even in “good little boys and girls.” I know Christie is presenting someone she deems insane, but what makes Crooked House so timely to me is that the “me first, carried to the extreme” attitude is all too prevalent today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Christie certainly sides with nature over nurture. This goes all the way back to Murder on the Links and in some of her later books it gets IMO really uncomfortable. That said, she does add a different interpretation here, with the nanny saying, that Jopsephine became evil because Magda called her nasty names. I don’t know which name was used in the English edition, because I only read the German one. Here, Mada said “Wechselbalg, which basically means that the girl was switched at birth”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The English word, “changeling,” has the exact same meaning. A changeling is a demon that looks like a child and is switched in the cradle when nobody is looking.

LikeLike

Just found out the new film is on UK TV tonight, so looking forward to watching it in about 10 minutes…

Really enjoyed your analysis, which was nail on the head, absolutely spot on. And if I think about it – I like Christies from all periods, but I think most of the ones I love would be 40s and 50s, so I’m with you there.

LikeLike

I’m cracking here, Moira. It’s supposed to open in the States on Friday, but there’s no guarantee it’ll open in my area. Meanwhile, I could just rent and watch it on iTunes! I might just have to do that tonight!!

LikeLike

Pingback: THE FACE OF ME BEING MAD: The Crooked House Movie | ahsweetmysteryblog

Pingback: THE BRIDGE TWIXT GAD AND MODERNITY: Christie’s The Body in the Library | ahsweetmysteryblog

Hi Brad fantastic analysis of Crooked House which I just finished. And although I knew in my heart who the murderer was just from reading the quote on the back of ‘a shocking surprise finish’ (I mean there can only be one ‘shocking surprise finish’ – none of the adults would have been ‘shocking’) I was still surprised because Josephine was such a likeable maniac. While I’m here I was wondering what your favorite Christie books are as Crooked House was the first Christie I have read in a long long time.

LikeLike

Hi, Warren! Thanks so much for visiting and for your kind words! I think my favorite Christies probably change with each passing day, depending on my mood. And just because they’re my favorites doesn’t mean they’re the best. So today, November 15, 2018, my thirteen ten Christies are:

Murder on the Orient Express

Cards on the Table

Death on the Nile

Hercule Poirot’s Christmas

And Then There Were None

Five Little Pigs

The Moving Finger

Towards Zero

The Hollow

A Murder Is Announced

Mrs. McGinty’s Dead

After the Funeral

The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side

That’s in chronological order, not preference, and already I regret my answers!!!

What are your favorites?

LikeLike

Hi Brad, I can’t say I have even read ten Agatha Christie books but I read a few of them when I was a teen: And then there were none, Murder on the Nile, Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case, The Mysterious Affair of Styles. I even remember reading a Mad Magazine parody of the movie Murder on the Orient Express which was very funny but they gave away the ending!

I decided to read Crooked House because I wanted to see what I thought of her thirty years later. She holds up very well. I like her lean mean style of writing. She definitely predated George Orwell’s writing advice of “Never use a long word where a short one will do.”

I am currently reading The ABC Murders as I thought it would be interesting what she did with a serial killer. Speaking of which, even though she didn’t coin the term she comes close when he is described as a ‘series’ killer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Actually, Warren, I was just ruminating today how much I love what Christie does with “series” killers in her work. Curtain, ABC, Murder Is Easy, And Then There Were None, The Pale Horse . . .each is a completely different approach to the idea.

I’m glad you’ve returned to Christie. I hope you’ll tackle many more and that you’ll come by and let me know what you think of the one’s you’re reading! 🙂

LikeLike

thanks Brad will do. One more thing about the ABC murders so far: I think it was (I’m not sure if this is the right word) ‘cute’ to discover that Poirot had read his Sherlock Holmes and makes a joke about it.

LikeLike

Pingback: Crooked House (1949) by Agatha Christie – crossexaminingcrime

Pingback: A CENTURY OF AGATHA CHRISTIE, PART THREE: Death – and Depth – in the 1940’s | ahsweetmysteryblog

Pingback: My Book Notes: Crooked House, 1949 by Agatha Christie – A Crime is Afoot

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX (The Blog-iography!) | Ah Sweet Mystery!