Author and blogger Margot Kinberg, who comes up with something thought-provoking every . . . single . . . day . . . recently offered up a tantalizing article about illusion. Her focus was on characters in mysteries whose lives, built to varying degrees around an illusory view of the world around them, form the crux of the book’s plot. After a tease about an unnamed Christie novel – I think I know which one you mean, Margot, and it’s one of my favorites – she offered several examples, proving once again that she is one of the most well-read purveyors of thought on the genre around. She included one of my favorite novels, Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and she succeeded in provoking much contemplation on my part about the topic. So, thank you, Margot, for inspiring me once again.

Illusion and the mystery genre go hand in hand. Throughout the Golden Age, the primary use of this element was external. The killer’s plot was built on illusion, designed to convince witnesses and, through them, the police, to look at the sequence of events wrong way round. This may have been done to provide the killer with an alibi, or to frame another person for the crime – or a combination of both.

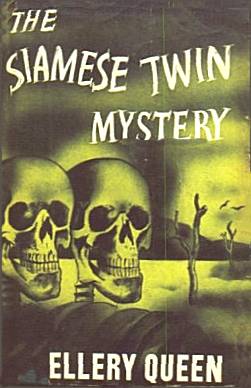

We love external illusion because, by and large, we know full well that the illusion exists, and our job is to attempt to see through it. This gets tricky because, more often than not, we don’t understand where the illusion lies or how it is shaped. In Three Act Tragedy (1935), Agatha Christie manipulates us into asking the question – “By what means could a killer have poisoned Reverend Babbington?” – which starts us down a road that turns out to be the wrong way round. Christie is the expert at getting us to look at things from a skewed perspective. Ellery Queen tackles it in a different way by making Ellery the self-proclaimed expert at identifying the illusion and casting it aside. The cleverness comes from the authors willingness, as in The Siamese Twin Mystery (1933), to hoist young Ellery on his own petard: inspired by the Gothic setting and the imminent danger of an encroaching forest fire, our hero manufactures illusions that aren’t there and almost comes a cropper in the end.

More than any other, impossible crime mysteries revel in external illusion, either because the killer’s ego inspires him to challenge the public’s perception or because certain events, happening fortuitously, create the semblance of an impossibility. Nobody mastered the art of illusion like John Dickson Carr, and his record for creating credible motivations for why an impossibility occurred is quite good. Yes, there are those who can’t swallow these sorts of plots because of their outrageousness. The solution to Frank Dorrance’s murder in The Problem of the Wire Cage(1939) veers toward the ridiculous, especially when you try to picture it happening. Still, there is plenty of motivation for the killer to kill Frank this way, and it has to do, in great part, with preserving an illusion.

But that’s what Golden Age killers do: create an illusion to support the delusion that murder is the answer to all their troubles. As you may imagine, it is well nigh impossible to discuss this aspect of illusion – the murderer’s plot – without spoiling things right and left. I’m not going to even try. But there are other ways that an author like Agatha Christie utilized the concept of illusion. Modern readers – and some similarly misguided authors like P.D. James – relegated Christie and her ilk to a senescent generation mired in the tiresome tropes of the literary long ago. Christie was far savvier than that. Yes, she continued to produce “classic” style mysteries of admittedly decreasing quality till the end of her career. But she knew this! She understood the trends, and she played with her faithful readers, taking advantage on our knowledge of GAD tropes, many of which she had invented or refashioned, to sometimes trick us and sometimes lay a foundation for something even richer than she had attempted before. The best part of At Bertram’s Hotel (1965) is how Christie embarks on a seemingly welcome sojourn into the past and then not only pulls the rug out from under us but gently scolds us for looking backward with such unmitigated fondness.

Two of the best Miss Marple mysteries – 1950’s A Murder Is Announced and 1962’s The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side – both contain murder plots where the web of illusion is woven thick, but there are other factors to consider as well. The post-war village we enter in 1950 seemslike the jolly hamlets of old, with thriving teashops doing a brisk trade and neighbors running in and out of each other’s houses. But the teacakes aren’t very good anymore, and the neighbors are mostly newcomers, allowing for secrets galore. As for Mirror, one of the most interesting elements is the illusions that the victim has about herself (something we see a lot of in village mysteries, old and new) as a do-gooder and a selfless soul. People like this often find themselves lying on the hearthrug with a stiletto between the shoulders or, as here, handed a lethal cocktail at the fete.

With the passing of World War II, social preoccupations with our psychological health inspired deep and lasting changes in the murder mystery. And as the focus became more internalized, the use of illusion shifted to the mental/emotional make-up of the characters rather than the clever touches of a murder plot. Some classic writers, like Christie and Carr, only flirted with the notion, satisfying themselves with greater character development even as they maintained a focus on the external puzzle. Others, like Queen, began to shift toward more psychological tricks. The killers in Ten Days Wonder (1948), The Origin of Evil (1951) and The Scarlet Letters (1953) are playing mind games with their victims, while in the ghost-written novels The Player on the Other Side (1963) and And on the Eighth Day (1964), the use of illusion is literally mind-boggling.

More and more new writers emerged who combined both elements of illusion in works that preserved most of the Golden Age traditions and yet proved to be harbingers of the modern psychological thrillers that readers gobble up today. One of the best was Helen McCloy, whose series sleuth, Basil Willing, was himself a psychologist. This mash-up of old and new reached its apotheosis in her 1950 classic, Through a Glass Darkly, where the exploration into the main character’s inner mind almost convinces us that doppelgangers do indeed exist. The solution may be external (and, given the time in which this was written, is the least convincing aspect of the plot), but the rest is all a highly effective internalized horror show

Despite the fact that the Golden Age of Detection existed when the world was either in the throes of war or whilst conflict was impending or receding, I would venture to say that modern mystery fiction is being written for a darker, more complicated society. We all struggle more to maintain a decent life for ourselves, and we tamp down that struggle by trying to create a semblance that all is well. Everyone’s in therapy, everyone practices wellness, to the point where one wonders about its long-term effectiveness. And art nowadays reflects a greater darkness. Books, films, TV, and video games display graphic violence with no regard for its audience. Only the other night, I met up with a friend, a 2ndgrade teacher, who bemoaned the fact that her students are more focused on their obsession for the Battle Royale murder game Fortnight than on their lessons.

We are all besieged by enormous changes to our socio-political structures, to the ways we communicate and learn, to seismic divisions in the ways we and our neighbors believe, even to great uncertainties about our planet’s very survival. No wonder we gravitate toward books where the very fabric of reality is uncertain. The unreliable narrators, the dystopian world-building, the mysteries that are the opposite of fair-play – these seem to be our artistic bread and butter these days. The hit Netflix movie Birdbox defines its terrors but never shows them; it’s enough that we witness their effect on people like you and me. And all those Gone Girl on the Train with the Woman in the Window by the Other Woman Who Sometimes Lies books offer this precis: Do not believe what I set up for you for the first two hundred fifty pages of this book, for in the final twenty pages I will pull the rug out from under you so that you fall on your ass!

Personally, while I never seem to get tired of the plot wheel variations of Golden Age whodunnits, I have become immune to the miasma surrounding the modern mystery fables. Who cares if the narrator has a multiple personality or her best friend is an imaginary person? What does it matter if the creepy guy down the street is an abused-child-turned-reluctant-hero while the kindly babysitter is a sociopath? Somehow, in the 1930’s the majority of characters were saved in the end when the illusion that any character could be a murderer was resolved in by a gathering in the library. Nowadays, authors are so effective at making everyone so grossly unpleasant that nobody can be saved. Nowadays, the gut punch endings of every book reveal that the illusion is never resolved because the madness never dies. Given how torched the landscape usually is at the end of a modern mystery novel, maybe the world of illusion is where I want to remain.

Thank you, Brad, for the kind words. That means a lot to me, coming from someone whose knowledge I respect as I do yours. And, yes, I do think you know the Christie I was referring to…

I really like the way you trace the use of illusion, both by GAD writers and more recent writers. It’s moved through crime scenes, ‘impossible’ crimes, and so on to more psychological illusions. Even some of the GAD writers played with that (I’m thinking, for instance, of Ethel Lina White’s The Wheel Spins). And it makes me think about the development of our understanding of psychology, and the way the mind can delude itself. As we’ve learned more about how the mind works, perhaps writers have felt more comfortable exploring that sort of illusion rather than the sort that a fictional murderer uses to deceive others? Whatever the explanation, illusion and crime fiction seem to be integrally related. Thanks for showing us how it’s worked.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s not the province of new writers only, Margot. Poe explored the psychology of guilt leading to illusion in “The Telltale Heart.” So did Dostoevsky in Crime and Punishment. The mind plays tricks on us all and has done so for countless generations!

LikeLike

Lament for the Murderers

– A.D. Hope

Where are they now, the genteel murderers

And gentlemanly sleuths, whose household names

Made crime a club for well-bred amateurs;

Slaughter the cosiest of indoor games?

Where are the long week-ends, the sleepless nights

We spent treading the dance in dead men’s shoes,

And all the ratiocinative delights

Of matching motives and unravelling clues,

The public-spirited corpse in evening dress,

Blood like an order across the snowy shirt,

Killings contrived with no unseemly mess

And only rank outsiders getting hurt:

A fraudulent banker or a blackmailer,

The rich aunt dragging out her spiteful life,

The lovely bitch, the cheap philanderer

Bent on seducing someone else’s knife?

Where are those headier methods of escape

From the dull fare of peace: the well-spiced dish

Of torture, violence and brutal rape,

Perversion, madness and still queerer fish?

All gone! That dear delicious make-believe,

The armchair blood-sports and dare-devil dreams.

We dare not even sleep now, dare not leave

The armchair. What we hear are real screams.

Real people, whom we know, have really died.

No one knows why. The nightmares have come true.

We ring the police: A voice says “Homicide!

Just wait your turn. When we get round to you

You will be sorry you were born. Don’t call

For help again: a murderer saves his breath.

When guilt consists in being alive at all

Justice becomes the other name for Death.”

LikeLiked by 3 people

Fabulous poem, Roger! Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

A.D. Hope?!?!

LikeLike

https://www.poetrylibrary.edu.au/poets/hope-a-d

LikeLike

I had English classes in the A.D. Hope Building at the Australian National University. Apparently he had an eye for a pretty girl even in his 80s.

LikeLike

In some ways, a good detective story is less about spending time in another world and more about having a direct conversation with the author. Some of Christie’s characters are certainly memorable, but my own recollections of her writing involve matching wits with Agatha herself. I usually lose — she always has the advantage of creating the damned thing. Perhaps the external illusion you refer to is connected to this aspect of detective fiction. Recently, I sent a manuscript to a friend. He began reading and then stopped, writing to inform me that he would continue after he had purchased some firewood. Naturally, I asked why. He said it was the kind of story one should read next to a fire. I kind of understand. The experience of reading a detective story is more important than the actual world within the pages. As for your description of interior illusion — there must be motivation, but that motivation is not what is fascinating. A few quick lines near the end should do. I’ll take “I killed him because he stole my teddy bear” over a deep psychological analysis any day. Great post.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I love the perspective you present here, James. Yes, we are matching wits with the author; that’s exactly what I meant by “exterior illusion.” (I just didn’t know that!) Yet, by extension, most murderers are creating the illusion themselves. I don’t know how well read in Christie you are, so i won’t give specific titles. But the canon is literally strewn with examples of men and women manipulating the other characters’ sense of reality in order to get away with murder. Making people appear to be alive when they’re not, or dead when they’re not, or present when they’re absent, or vice versa . . . the list of tricks goes on and on, thank God! However, there are examples within books where – completely separate from the killer – Christie is creating an illusion to trick the reader. One of my favorite occurs in After the Funeral; these sorts of tricks are my very favorite.

LikeLike

This is a fantastic and thought-provoking read Brad. I think you picked some wonderful examples (I will always be happy to read thoughts about At Bertram’s Hotel).

One of the things I appreciate about the Agatha Christie podcast you discussed a few months ago is the way they describe the world as it appears to be. It wasn’t a phrase I had encountered before with detective fiction but it has been eye opening as I find myself considering the staging of a crime more and more.

I will say that I find it most satisfying when there is an in-universe reason for an illusion to exist rather than just to fool a reader. Whether it is created to cover up some family secret or an illusion being created by one character for another’s benefit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When the illusion is part of the murderer’s plan, there is always a chance for fair play. When it is a ploy by the author to fool the reader, the situation becomes more problematical. That example I alluded to above from After the Funeral? It’s absolutely effective . . . but highly suspect as fair play, even if Christie essentially, . . . er, plays fair!

Damn this high-minded attempt to avoid spoilers!!!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haven’t read any of the current thrillers, so I speak from sheer ignorance – but aren’t they part of a long tradition? The Tell-Tale Heart, as you say. Hangover Square. Before the Fact. Golden Age mysteries were never as tidy as people like to make out. No blood? Try Have His Carcase.

LikeLike

“Still, there is plenty of motivation for the killer to kill Frank this way, and it has to do, in great part, with preserving an illusion.”

I forgot just how much I enjoyed that element of The Problem of the Wire Cage. There’s a beauty in everything that goes right, and of course, everything that goes wrong. An excellent example of why a crime ends up being impossible.

LikeLiked by 1 person