If I was a Londoner, I’d spend my evenings with my mates Daniel (The Reader Is Warned) and JJ (The Invisible Event), study-hopping between each other’s flats or spending an evening in the pub over Scotch eggs, bangers and mash, backed bubble and squeak, (do you people eat anythingnormal?), having a rigorous back and forth over all things associated with the Golden Age of Mystery.

I would also find a means of rudely pushi- inveigling my way onto their delightful podcast, The Men Who Explain Miracles. While both of them rank far above me in their knowledge of, and passion for, all things locked, un-footprinted, pseudo-haunted and in all ways impossible, I could be their Old Man in the Corner, their Mr. Satterthwaite, their Djuna – pouring the tea and offering an occasional comment that clarifies all that went before. (Wait! That would make me their Miss Marple . . . )

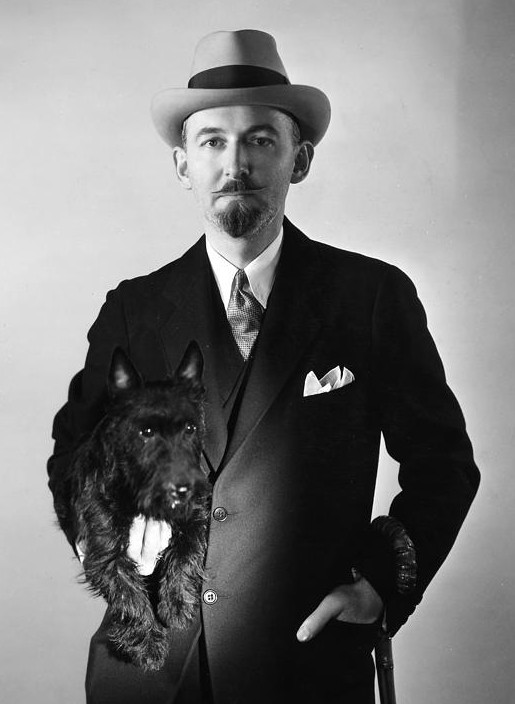

A lovely afternoon hanging out with Dan and JJ (that’s me in the middle).

A lovely afternoon hanging out with Dan and JJ (that’s me in the middle).

Once again, the Boys have inspired me with their latest episode – the first of a two-parter – in which they tackle The Rules. Authors S.S. Van Dine and Ronald Knox separately conceived a set of regulations by which all classic mystery authors were expected to abide. It’s arguable just how tongue in cheek these enterprises were, but I would venture to guess that Knox could laugh at himself more than Van Dine; this is pure supposition, however, based on the latter author’s ambivalent relationship with the genre that ironically made him the household name he had always wanted to be.

The first episode – which you can listen to here – focused on Van Dine’s Twenty Commandments. Of course, JJ and Dan examined the rules through the lens of locked room aficionados, while I sat back and listened with my brain attuned to none other than the Mistress of Mystery. Agatha Christie has been on my mind a lot lately, ever since I watched the latest BBC adaptation, The ABC Murders. The program has generated a great many varied reactions, and my own personal response prompted more of the same. Where Sarah Phelps and I disagree is over how “dark” Christie was, with Phelps claiming that her adaptations are simply the stories as Christie wanted to write them.

If I disagree with Phelps there – and I most vehemently do – this is not to say that I don’t credit Christie with a thorough awareness of the evil that men and women can do, with ample evidence of this splattered like blood across her literary canvas. Once more, I think Christie was one of the most ruthless of authors when it came to her characters. Nobody was guaranteed a happy ending in her books, not if such happiness stood in the way of Christie’s puzzle. She abided by certain tenets of classic mystery writing – unlike Van Dine, she embraced the genre and was well read in it – but she also broke many of the Rules. I thought it would be interesting to examine Christie’s relationship with Van Dine’s commandments. Such an exploration requires some spoilers, so I’m afraid you casual or beginning Christie readers must either tread past the parts marked SPOILER or part ways with me from this moment on.

VAN DINE’S TWENTY COMMANDMENTS

Herewith, then, is a sort of Credo, based partly on the practice of all the great writers of stories, and partly on the promptings of the honest author’s inner conscience. To wit:

1. The reader must have equal opportunity with the detective for solving the mystery. All clues must be plainly stated and described.

I think this first commandment is the single most inarguable descriptor of classic detective fiction. Most authors who break it are either bad writers or are not writing GAD fiction. We can argue the effect till the cows come home, but Christie’s intent throughout her career was to lay out a case before her readers, at which point they could race the detective to the denouement. Neither Poirot, Miss Marple, the Beresfords or any other detective willfully held back information from the reader that later proved so valuable to the case that without it, the mystery would be unsolvable.

This is not to say that all clues are created equal in Christie. The piece of pink rubber in Hercule Poirot’s Christmas probably ranks as one of her worst clues. She can have a balloon float ludicrously by at a late moment in the story. She can have someone speak of animals in distress. There is no clear path here for most readers to figure out what that piece of rubber represents. Still, Christie supplies us with other, better, clues regarding the killer’s identity, and once you get that, you might have more luck figuring out the rest of the case. I say again: you might!

2. No willful tricks or deceptions may be played on the reader other than those played legitimately by the criminal on the detective himself.

FIRST RULE BROKEN! For the most part, Christie adheres to this rule because she wants to play fair, and the detective must have all the facts. But sometimes, her cleverness with the language and tactics of mystery inspires her to play a trick on the reader. This is especially true in the latter part of her career when she was less likely to present her whole tale from the general point of view of the sleuth and more likely to take us into the minds and hearts of her suspects.

SPOILERS-EXAMPLES-SPOILERS*

At the start of After the Funeral, Aunt Cora causes an uproar amongst the Abernethy family by announcing at her brother Richard’s funeral that he was murdered. The next section follows each of the relations as they take trains and cars back to their houses, showing their reactions to batty old Cora’s revelation. One of these passages shows us Cora herself, sitting in a café, having her tea, and feeling exhilarated about the stir she caused. EXCEPT . . . Christie never actually names the woman to whose thoughts we have been made privy. What’s more, at the very end of the passage, something happens which gives a large hint as to the intriguing motive behind this complex murder plot.

Another example occurs in Third Girl, when Frances Cary discovers the murdered body of David Baker, the main suspect’s boyfriend. Christie presents this discovery from Frances’ point of view: coming upon the body, Frances stops, looks up to see her face reflected in a mirror, and then screams. Yet Christie never actually takes us into Frances’ mind, so we have no way of knowing her purpose for looking at herself (to check on whether she looks suitably shocked to find the body of the man she herself has killed!)

The final and, perhaps most famous, example occurs in Christie’s first great shocker, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. We must remember that Dr. Sheppard is writing his memoir of the case as he awaits execution for his crimes. Hercule Poirot doesn’t get to read it; only the reader is given this private access to the mind of a killer. And Sheppard is playing a game with us: the way he describes certain things, like his course of actions upon taking leave of Ackroyd or the phone call he receives that takes him back to Ackroyd’s house – all of these are tricks the author (Sheppard/Christie) is playing on the reader, not the sleuth.

3. There must be no love interest in the story. To introduce amour is to clutter up a purely intellectual experience with irrelevant sentiment. The business in hand is to bring a criminal to the bar of justice, not to bring a lovelorn couple to the hymeneal altar.

SECOND RULE BROKEN! One could write about this rule ad infinitum! In fact, I have posted two articles about love and Christie: one concerns the deadly duos that crowd the canon – those pairs united by passion to commit a deadly act – and the other lists a few great love matches found in Christie’s novels.

I suppose that what Van Dine is really alluding to here is the idea of crowding a tense mystery with romantic interludes. I agree that one thing that differentiates the modern mystery from the classic is the modern writer’s tendency to focus on the private lives of the characters at the expense of the case. This is what has undone Elizabeth George, where if you cut, say, the 150 pages of her last two books devoted to Thomas Lynley’s tortured relationship with the zookeeper, the books might approach a more palatable length.

But love is one of the two most powerful emotions, a likely motivation to act, whether chivalrously or murderously, and something that will no doubt occupy the thoughts of the multitude of female protagonists found in the canon. As I stated above, Christie was one of the most ruthless female writers of them all, showing us from nearly the beginning that we can trust no one, including an attractive lover. She has great fun with this, too, providing a myriad of alternative routes to the solid romantic question: “Who is X’s Mr. Right?” Here are eight examples (SPOILERS AHEAD):

Three Act Tragedy (1935): The lady in question: Hermione “Egg” Lytton-Gore. She is part of the crime-solving quartet and the beloved of Charles Cartwright. Her presence humanizes Cartwright in our eyes because, if there’s one fact honestly presented here, it’s that Charles adores Egg. And so, significant page time is set aside to create this attractive romance – for a reason!

Death in the Clouds (1935): The lady in question: Jane Grey. During the investigation into who murdered Madame Giselle, Jane acquires two suitors, and Christie manipulates us to root for Norman Gale. He’s appealing, and Christie has let us into his thoughts at the beginning of the novel to show that he finds her maddeningly attractive. Together they work with Poirot to solve the case, and the sleuth becomes “Papa” in his determination to find Jane a husband. The other suitor, archaeologist Jean Dupont, is perfectly likable, but he is a foreigner and is presented more in connection with his father than in a romantic capacity. It’s all part of Christie’s plan to hide her murderer in plain view.

Death on the Nile (1937): The lady in question: actually, there are several. What’s an exotic cruise without the promise of murderromance in the air? Who’s looking for love here (sometimes without even knowing it): Rosalie Otterbourne, Cornelia Robson, Tim Allerton, Jim Ferguson, Dr. Bessner, Louise Bourget. Never mind that the whole plot hinges on one of the great love affairs in Christie: all these side side characters interact with each other and eventually pair off (or go home alone!)

This roundelay of romance is common in the larger cast Christie stories. The members of the Boynton family each have their romantic intrigues in Appointment with Death (1938) and each end up married in what might be Christie’s stickiest and silliest epilogue. There’s a do-si-do of partners, past and present, going on throughout Towards Zero (1944) and The Hollow (1946), but fortunately this is the 1940’s and Christie eschews sentiment by pairing off the minor characters (Mary and Thomas, Midge and Edward) and letting the major ones suffer the loss of their love. (At least poor Henrietta has her art!)

Death Comes As the End (1945) concerns itself almost as much with beautiful young widow Renisenbs’ romantic prospects as it does with the serial killer decimating the members of her family. Given her two prospects – the sober, thoughtful Hori and the winsome, playful, handsome Kameni – it seems likely that one or the other might turn out to be the killer in the end. Christie plays a bit with this before taking us in a different situation entirely. This leaves poor Renisenb with a problem: since murder did not eliminate one of the suitors, she must choose. Given Christie’s own experience with winsome, playful, handsome men, we know there is only one possible choice.

Final example: Taken at the Flood (1948): Lynn Marchmont, home from the wars, has to settle down with the proper husband. Will it be loyal stick-in-the-mud Rowley Cloade or handsome-as-the-devil bad boy David Hunter? Lynn’s choice resembles Renisenbs’ taken to an extreme, and it’s anybody’s guess whether the good guy or the bad guy will turn out to be a murderer. (Surprise: both of them are!)

4. The detective himself, or one of the official investigators, should never turn out to be the culprit. This is bald trickery, on a par with offering someone a bright penny for a five-dollar gold piece. It’s false pretenses.

THIRD RULE BROKEN! There’s no need to go into it. Christie broke this rule several times. It is one of her trademarks that everyone must be suspected, and in one of her earliest efforts here she states that “one forgets that policemen are human, too.”

5. The culprit must be determined by logical deductions–not by accident or coincidence or unmotivated confession. To solve a criminal problem in this latter fashion is like sending the reader on a deliberate wild-goose chase, and then telling him, after he has failed, that you had the object of his search up your sleeve all the time. Such an author is no better than a practical joker.

This is as basic a tenet to classic mystery writing as Rule #1, and to my mind, Christie never went out of her way to break it. If we all differ on the success of various titles in being truly logical – particularly in any case not featuring Poirot – it was not for lack of trying on the author’s part.

6. The detective novel must have a detective in it; and a detective is not a detective unless he detects. His function is to gather clues that will eventually lead to the person who did the dirty work in the first chapter; and if the detective does not reach his conclusions through an analysis of those clues, he has no more solved his problem than the schoolboy who gets his answer out of the back of the arithmetic.

Done and done. Even when the sleuth is the basest amateur – Charles Hayward in Crooked House, Arthur Calgary in Ordeal by Innocence, Jane Marple in, oh, everything she’s in! – they are assisted, not always willingly, by the official police, yet it’s the amateur with whom we identify and who comes up with the actual solution.

7. There simply must be a corpse in a detective novel, and the deader the corpse the better. No lesser crime than murder will suffice. Three hundred pages is far too much pother for a crime other than murder. After all, the reader’s trouble and expenditure of energy must be rewarded. Americans are essentially humane, and therefore a tiptop murder arouses their sense of vengeance and horror. They wish to bring the perpetrator to justice; and when “murder most foul, as in the best it is,” has been committed, the chase is on with all the righteous enthusiasm of which the thrice gentle reader is capable.

This is really a matter of taste. Read The Moonstone, Mr. Van Dine. But I, too, feel cheated when there’s not a murder, and Christie never disappoints there. (I’m a little worried about my future read of Carter Dickson’s And So To Murder however . . . )

8. The problem of the crime must be solved by strictly naturalistic means. Such methods for learning the truth as slate-writing, ouija-boards, mind-reading, spiritualistic seances, crystal-gazing, and the like, are taboo. A reader has a chance when matching his wits with a rationalistic detective, but if he must compete with the world of spirits and go chasing about the fourth dimension of metaphysics, he is defeated ab initio.

This rule fascinates me! Were there psychic sleuths out there in the 1920’s-30’s who communed with the spirits to get the job done? Christie’s plots were grounded in the natural world, and whenever she incorporated the occult, you could bet that there was a clue lurking in the ectoplasm.

SPOILERS HERE: When Katherine Cloade arrives at Hercule Poirot’s door at the start of Taken at the Flood with a message from the beyond, we recognize that perhaps Aunt Kathie is not the flake she pretends to be. When ethereal phenomena manifests itself from out of Emily Arundell’s mouth during a séance with the Tripp sisters, there’s not a chance in the world that Miss A. is possessed by demons and every likelihood that we should be taking our manual on poisons down from the shelf. The most significant example occurs at the top of The Sittaford Mystery as a séance ends with a warning of Captain Trevelyan’s death, sending his best friend, Major Burnaby, down to the village to investigate. And since we just know that there’s no such thing as spooks, we have to ask ourselves who made the table rap out the warning message. And then we have to ask ourselves who had access both to the séance and to the dearly departed Captain. And that is how I solved The Sittaford Mystery!

9. There must be but one detective–that is, but one protagonist of deduction–one deus ex machine. To bring the minds of three or four, or sometimes a gang of detectives to bear on a problem is not only to disperse the interest and break the direct thread of logic, but to take an unfair advantage of the reader, who, at the outset, pits his mind against that of the detective and proceeds to do mental battle. If there is more than one detective the reader doesn’t know who his co-deductor is. It’s like making the reader run a race with a relay team.

FOURTH RULE BROKEN . . . SORT OF. I’ll grant you that when Hercule Poirot is in charge, he is in charge! But he often gathers a group together to help him out: Three Act Tragedy, The ABC Murders, Death in the Clouds. All of these tales include a cabal of “assistants” who aid Poirot in his search for the killer. Of course, when this happens, the killer often tends to be closer to home than anyone thinks.

But there is one clear example where a group of detectives work together: Cards on the Table (1936). And while we can argue that Colonel Race takes off early, and Mrs. Oliver is dithery, and Superintendent Battle is wooden, and Poirot still gets to give his denouement at the end, he isn’t the first to hit on the truth! Just sayin’.

10. The culprit must turn out to be a person who has played a more or less prominent part in the story–that is, a person with whom the reader is familiar and in whom he takes an interest. For a writer to fasten the crime, in the final chapter, on a stranger or person who has played a wholly unimportant part in the tale, is to confess to his inability to match wits with the reader.

I absolutely agree with this rule . . . and so, apparently, did Christie! Check!

11. Servants–such as butlers, footmen, valets, game-keepers, cooks, and the like–must not be chosen by the author as the culprit. This is begging a noble question. It is a too easy solution. It is unsatisfactory, and makes the reader feel that his time has been wasted. The culprit must be a decidedly worth-while person–one that wouldn’t ordinarily come under suspicion; for if the crime was the sordid work of a menial, the author would have had no business to embalm it in book-form.

This is such an awful, snobbish, head-up-your-ass rule that it’s hard to give it any of our time or credence as decent modern citizens. Christie never made a servant the brains behind a crime in her novels, but her short stories are another matter. There are a few cases where a servant was an accomplice – willing or unwitting – to the main criminal, or committed a secondary crime, like theft – but Christie separated the classes as Van Dine suggested. I suppose we can take comfort in the wealth of fine character portraits of maids, housekeepers, and especially butlers that sprang from her pen.

12. There must be but one culprit, no matter how many murders are committed. The culprit may, of course, have a minor helper or co-plotter; but the entire onus must rest on one pair of shoulders: the entire indignation of the reader must be permitted to concentrate on a single black nature.

FIFTH RULE BROKEN! I refer you to my past post on “Deadly Duos” (see above.)

13. Secret societies, camorras, mafias, et al., have no place in a detective story. Here the author gets into adventure fiction and secret-service romance. A fascinating and truly beautiful murder is irremediably spoiled by any such wholesale culpability. To be sure, the murderer in a detective novel should be given a sporting chance, but it is going too far to grant him a secret society (with its ubiquitous havens, mass protection, etc.) to fall back on. No high-class, self-respecting murderer would want such odds in his jousting-bout with the police.

Christie loved the Edgar Wallace-type adventure about world-wide conspiracies, but she managed most of the time to keep her thrillers separate from her detective stories. There was NEVER a pure whodunnit that featured a secret society. However, her thrillers all had whodunnit elements, so one may argue about whether The Seven Dials Mystery, The Big Four, Destination Unknown and my favorite thriller, The Pale Horse, break the rules. I don’t think they do.

14. The method of murder, and the means of detecting it, must be rational and scientific. That is to say, pseudo-science and purely imaginative and speculative devices are not to be tolerated in the roman policier. For instance, the murder of a victim by a newly found element–a super-radium, let us say–is not a legitimate problem. Nor may a rare and unknown drug, which has its existence only in the author’s imagination, be administered. A detective-story writer must limit himself, toxicologically speaking, to the pharmacopoeia. Once an author soars into the realm of fantasy, in the Jules Verne manner, he is outside the bounds of detective fiction, cavorting in the uncharted reaches of adventure.

Well, there’s “Calmo,” or whatever it’s called, in The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side, but that’s a pharmacological invention that fits in with actual drugs. I fear that Christie might have dallied with something impossible in one of her thrillers or short tales, but let’s face it: mobody knew their poisons as well as she did, and she played with them to amazing – and totally fair – effect. One can argue that nobody could solve The Mysterious Affair at Styles or The Pale Horse without being aware of the scientific properties of the poison in question. Sure, I’ll give you that, but the rule remains unbroken. All the other weaponry Christie employs can, I think, be purchased through ACME Weapons, the catalogue of choice of Wile E. Coyote.

15. The truth of the problem must at all times be apparent–provided the reader is shrewd enough to see it. By this I mean that if the reader, after learning the explanation for the crime, should reread the book, he would see that the solution had, in a sense, been staring him in the face–that all the clues really pointed to the culprit–and that, if he had been as clever as the detective, he could have solved the mystery himself without going on to the final chapter. That the clever reader does often thus solve the problem goes without saying. And one of my basic theories of detective fiction is that, if a detective story is fairly and legitimately constructed, it is impossible to keep the solution from all readers. There will inevitably be a certain number of them just as shrewd as the author; and if the author has shown the proper sportsmanship and honesty in his statement and projection of the crime and its clues, these perspicacious readers will be able, by analysis, elimination and logic, to put their finger on the culprit as soon as the detective does. And herein lies the zest of the game. Herein we have an explanation for the fact that readers who would spurn the ordinary “popular” novel will read detective stories unblushingly.

If Scott Ratner shows up here, he will tell you that 1) the “game” referred to here is not a game as we know games to be, and 2) it isn’t really possible for a mystery writer to be totally “fair play” since the whole thing is artificial and manipulated by the author to be what she needs for it to be. I’m sorry, Scott, I’m sure I got that a little wrong, but that is essentially the idea here.

Within Scott’s parameters or without, I posit that Christie was an enthusiastic player of the “game” and that her goal was to get the rules right every time. If she carped on clues or occasionally forgot to close a loophole, I put it down to human error. Her aim was to follow this rule, and she did, often with tremendous success.

16. A detective novel should contain no long descriptive passages, no literary dallying with side-issues, no subtly worked-out character analyses, no “atmospheric” preoccupations. Such matters have no vital place in a record of crime and deduction. They hold up the action, and introduce issues irrelevant to the main purpose, which is to state a problem, analyze it, and bring it to a successful conclusion. To be sure, there must be a sufficient descriptiveness and character delineation to give the novel verisimilitude; but when an author of a detective story has reached that literary point where he has created a gripping sense of reality and enlisted the reader’s interest and sympathy in the characters and the problem, he has gone as far in the purely “literary” technique as is legitimate and compatible with the needs of a criminal-problem document. A detective story is a grim business, and the reader goes to it, not for literary furbelows and style and beautiful descriptions and the projection of moods, but for mental stimulation and intellectual activity–just as he goes to a ball game or to a cross-word puzzle. Lectures between innings at the Polo Grounds on the beauties of nature would scarcely enhance the interest in the struggle between two contesting baseball nines; and dissertations on etymology and orthography interspersed in the definitions of a cross-word puzzle would tend only to irritate the solver bent on making the words interlock correctly.

(My god! This rule lasts longer than any descriptive passage Christie ever wrote!) I find it ironic that one of the biggest criticisms of the author might be the result of her following Rule #16 to the letter. I don’t think she saw it as a rule, but her economy of writing, the thing that gets her into such trouble with snobby book reviewers and P.D. Jamesian scholars (include James herself!) is what makes her the best-selling mystery writer of all time. Hell, it’s what makes people rush to James Patterson: that accessibility of language and focus on story that propels readers through their books. And now that I have compared Christie to James Patterson, I’m going to take a long, hot shower with a scrub brush.

17. A professional criminal must never be shouldered with the guilt of a crime in a detective story. Crimes by house-breakers and bandits are the province of the police department–not of authors and brilliant amateur detectives. Such crimes belong to the routine work of the Homicide Bureaus. A really fascinating crime is one committed by a pillar of a church, or a spinster noted for her charities.

I can think of several occasions where the murderer turns out to be a professional criminal . . . and yet I don’t think Christie breaks this rule because that aspect of the killer’s identity is hidden from view until the end. The con artist who repeatedly murders spouses, the Mata Hari-type spy, the head of a gang of smugglers or thieves or drug dealers – these all appear in her books, in suitable disguise. I’m satisfied.

18. A crime in a detective story must never turn out to be an accident or a suicide. To end an odyssey of sleuthing with such an anti-climax is to play an unpardonable trick on the reader. If a book-buyer should demand his two dollars back on the ground that the crime was a fake, any court with a sense of justice would decide in his favor and add a stinging reprimand to the author who thus hoodwinked a trusting and kind-hearted reader.

SIXTH RULE BROKEN . . . SORT OF. We never come to the end of a Christie novel with the realization that there has been no crime. But I can think of two cases where a death was not a murder. SPOILERS AHEAD:

In the novella “Murder in the Mews” (1937), there is a murder being plotted, but it is the murder of the man responsible for the suicide of the woman whose “murder” was faked by the person trying to murder the man who . . . oh, help!

In There Is a Tide, we have three deaths, and they turn out to be a murder, a suicide, and an accident. I don’t think this variety improves the book, to be honest, but, in comparing the men responsible for three deaths, Christie offers us an interesting spectrum of guilt and evil.

19. The motives for all crimes in detective stories should be personal. International plottings and war politics belong in a different category of fiction–in secret-service tales, for instance. But a murder story must be kept gem tlich, so to speak. It must reflect the reader’s everyday experiences, and give him a certain outlet for his own repressed desires and emotions.

I have no idea what “gem tlich” means. Gemutlich is a German word meaning “pleasant and cheerful.” If that is Van Dine’s intent . . . I’m still confused. At any rate, Christie kept it personal where it needed to be. International plottings were left to the thrillers.

An unforgiveable moment in an otherwise fine film: Poirot battles the cobra in DotN!

An unforgiveable moment in an otherwise fine film: Poirot battles the cobra in DotN!

20. And (to give my Credo an even score of items) I herewith list a few of the devices which no self-respecting detective-story writer will now avail himself of. They have been employed too often, and are familiar to all true lovers of literary crime. To use them is a confession of the author’s ineptitude and lack of originality.

- Determining the identity of the culprit by comparing the butt of a cigarette left at the scene of the crime with the brand smoked by a suspect.

- The bogus spiritualistic seance to frighten the culprit into giving himself away.

- Forged finger-prints.

- The dummy-figure alibi.

- The dog that does not bark and thereby reveals the fact that the intruder is familiar.

- The final pinning of the crime on a twin, or a relative who looks exactly like the suspected, but innocent, person.

- The hypodermic syringe and the knockout drops.

- The commission of the murder in a locked room after the police have actually broken in.

- The word-association test for guilt.

- The cipher, or code letter, which is eventually unravelled by the sleuth.

Again, we have that love of the sensational in Christie’s thrillers. In Parker Pyne Investigates, the “cures” to people’s ailments that author Ariadne Oliver concocts often rely on these hoary clichés. As for the whodunnits . . . I think Christie had a good hand with clues, and when she incorporated these old chestnuts, she did it for a reason (Murder on the Orient Express).

The one device she may be considered guilty of is “f”, but the only time I can recall when the idea of look-alikes was crucial to the solution happened quite late in her career and was, to my mind, an utter failure. Her other “twins” were not at the center of the plot: think Murder on the Links. What Christie used to an excessive degree was disguise. It’s hard to imagine that as many people as we find here could be so successful at disguising themselves, particularly when they often would expose themselves – in disguise – to those closest to them. Sometimes it worked for me; sometimes it didn’t. But since it isn’t on Van Dine’s list, it doesn’t matter!!!

We’ve taken a long journey here, and I hope a few of you are still with me. I also hope I’ve proven to you – and to that Sarah Phelps! – that Christie could be a bad girl when she wanted to be and when it suited her . . . but on her terms, not Phelps’!

Be sure and listen to next week’s podcast over at The Invisible Event and The Reader Is Warned: their take on Knox’ Decalogue is sure to intrigue.

As always, Brad, a rich and thoughtful post. I’ve always liked the way that Christie played with readers’ expectations and the rules (Van Dine’s and others). That’s part of what makes her stories distinctive. There are, as you say, no guarantees about who will live (or won’t), or that the killer mus/can’t be a certain sort of character. You’ve mentioned some excellent examples,too; and, as you know, there are others. She took her share of criticism for flouting the rules, too,but I believe time has proved her right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When I think of the flak she took for Roger Ackroyd! And decades later, she was part of the forefront of a new sub-genre. Could Gone Girl have been written without authors like Christie paving the way?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good question! I don’t think it could have. And, since I commented on your post before, I’ve been thinking of all sorts of novels with innovative plots that would never have been published if it weren’t for her willingness to break the rules in service of a good plot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a very interesting topic.

But I’m wondering if van Dine meant, that the detective can’t have a love interest? Surely he can’t possibly mean that no love whatsoever is allowed in crime novels. I mean, I could agree that it doesn’t necessarily need to be in a crime novel. But saying that it shouldn’t been there at all hardly makes sense. By the way, related to that: Your spoiler made the ending of Taken at the Flood sound much better, than it actually is.

Sort of a spoiler regarding Hercule Poirot’s Christmas: I think that the pink rubber is less of a clue than the fact, that it was Magdalene Lee who told him about it, if you understand what I mean.

Also “gemütlich” can have several meanings in german, but the most common ones are comfortable (as in “an armchair can be confortable”) or cozy. I’m afraid van Dine probably meant that mystery novels should be cozy.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“But I’m wondering if van Dine meant, that the detective can’t have a love interest? Surely he can’t possibly mean that no love whatsoever is allowed in crime novels.” I think he did, as an overreaction to a habit of the time. There seems to have been a tendency in popular mysteries at that date (mostly the ones NOT by the classic authors we still read) to have a young-couple-falling-in-love as an intrusion on, and distraction from, the detection. We get a glimpse of this when Harriet Vane is at work on a book, and remembers that she is at the point where she is contractually obligated to include a romantic interlude — and decides she can’t bring herself to do it.

LikeLike

I think your average Golden Age eccentric detective was a loner and an outsider. Some of them – mostly the policemen – were married. Some detectives even met their future wives while on a case. Often, she was a suspect, initially, so the flirting could be combined with official business. I think Van Dine would have disapproved of Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane and all the time spent on their romance. Most of it is at least peripherally connected to detective work.

LikeLike

And he would have been right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not going to read this (you spoilerizing maniac!) but I think Agatha adhered to only one rule: I will try to fool you and make you glad I did. Both halves are equally important.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Because Dame Agatha knew – and I embrace – the fact that most of us true GAD fans want to lose the game every time!

LikeLiked by 1 person

#2 is really difficult, because of POV. Van Dine never broke this rule, because Van Dine stuck to the assistant’s point of view. I love his books (mostly I love Vance – he’s my fav detective), but the world would be a very boring place if all detective novels were written Van Dine’s way. I love it when the reader gets more information than the detective but subsequently misinterprets the meaning of that information.

LikeLiked by 1 person

James, that is exactly what my example from After the Funeral was all about! (See above . . . unless you haven’t read the book!) If Poirot had been there, the case would have never gotten off the ground. Christie lets us see something that questions a character’s motive for a certain act . . . and adds much confusion there! The cool thing is that since no detective WAS present at the time, nobody bothers to clear up this point. It’s just those of us who remember these things who get an extra “ahaaaah!” It’s like an Easter Egg in a movie!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Josef Skvorecky wrote “Ten Sins for Father Knox”, a book of short stories, each of which systematically breaks one of Knox’s rules. He never came across van Dine, as far as I know, though.

“backed bubble and squeak”

Do you mean baked bubble-and-squeak?

Bubble-and-squeak must always be fried.

LikeLike

I know NOTHING about “bubble and squeak,” but you and a FB friend have corrected me. Many thanks! Now I know another thing I don’t want to try!

LikeLike

Rule #11: Don’t tell Julian Fellowes about this one. He’d have to rethink Gosford Park in its entirety…

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re right! I forgot! And it’s one of my favorite movies!

LikeLike

Regarding the picture above with you in the middle, I don’t think that either JJ or Dan will be very flattered by the picture ! 🙂

LikeLike

I regard only 7 of the rules as essential: 1, 5, 6, 8, 10, 14, 15.

LikeLike

I just went through them all without reading your post, and came up with that same list of seven! (I hesitated over adding in 13 as well, but decided that it’s not really an issue.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is an interesting book Sins For Father Knox by Josef Skvorecky (translated from the Czech). It contains 10 detective stories featuring a night club singer Eve Adam. Each story violates one of the rules of Knox. Thus the task for the reader is twofold: to determine which rule of Knox has been broken and to identify the murderer. The 10 rules are given at the beginning of the book. In each story, there is a challenge to the reader before the solution is revealed.

LikeLike

This sounds like Gigi Pandian’s new book of locked room stories, where each tale involves one of JDC’s locked room situations. Given that you have the list before you, it seems to me that the author effectively spoils each tale as soon as the situation makes itself clear. I can’t imagine the challenges to the read in the Skvorecky book are all that challenging.

LikeLike

Well, the rules are not applied serially to the stories. Hence, one does not know beforehand which rule is broken in which story.

LikeLike