This is an analysis/reflection of a classic piece of mystery literature. Be warned that the identity of the murderer and other details salient to the plot will be revealed and discussed. Do not read this post if you have not already read the book.

I wonder.

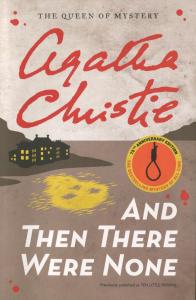

I wonder if Collins Crime Club sensed when it published And Then There Were None on 6 November 1939, eighty years ago today, that this would turn out to be, thus far, the most successful mystery novel ever written. This claim is both statistically verifiable and aesthetically just. Current sales estimates place it as approximately the sixth best-selling novel of all time – of any genre. It is read and loved by mystery and non-mystery fans alike; indeed, in his Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, E.D. Hirsch listed ATTWN as a must-read book for any “educated” person. And as late as 2015, Christie fans from over one hundred countries voted it the best of all her books.

Exposure helps. As Mark Aldridge points out in Agatha Christie on Screen, “. . . many people’s first experience of Agatha Christie is not through her original texts, but through adaptations of her work for film and television.” And Then There Were None has been adapted for the screen more than any other mystery, with four English-language films (1945, 1965, 1974, 1989) of diminishing quality, four loosely adapted films from India (including 1965’s Gumnaam, containing one of my favorite song sequences in all of Bollywood, although purists may scratch their head as to how this fit into Christie’s tale), a very good, very grim, very Russian adaptation, and numerous TV adaptations in England, the U.S., and Japan.

I love it so much that I’m linking it twice!!

I love it so much that I’m linking it twice!!

I wonder if these video fans know that the book itself is the very best of them all.

There were also three stage versions, the first by Christie herself, but these are distinctly problematic. Produced in wartime, Christie was convinced that the powerfully grim ending of the novel would not sit well with audiences. And so she gave the play a happy ending. Make no mistake: it’s entertaining, but she ruined it. To make matters worse, most of the film adaptations adopted this touch of happy romance in their screenplays. (The Russian version and the most recent BBC adaptation are the ones to see.)

A Scottish theatre company adapted the play the year after it opened in London and received permission to restore the original ending. All well and good, but unless you were in Dundee in 1944 (and again in 1965) . . . well, nuts to you. The third stage adaptation, by Kevin Elyot, played briefly in London a few years ago. I understand that it was a bloodbath, both onstage and in the critics’ reviews.

I wonder if Christie herself understood how significant the book would be as the starting off point of a whole new approach to her writing. If the nine titles of the 1920’s showed Christie finding her bearings, (and creating one classic with The Murder of Roger Ackroyd) and the sixteen mysteries from 1930’s Murder at the Vicarage to 1939’s Murder Is Easy, with their well-clued puzzles and trick endings, established her reputation as the Queen of Crime, And Then There Were None ushered in a third period of rich, character-driven mysteries that often chronicled the changing social climate of WWII and post-war England, achieving along the way an emotional resonance previously unseen in her writing.

It’s even more personal for me: ATTWN was the first Christie that I read, my gateway into the world of Golden Age Detective fiction. (You can listen to me talk about it here.) It ranks as one of my favorite books of any genre, and I want to publicly celebrate its eightieth birthday because, without getting too dramatic about it, And Then There Were None changed my life. On a fundamental level, reading Christie – and, because of her, Queen, Carr, Brand, Marsh, and the rest – provided me with the mental stability I needed to survive an emotionally tumultuous youth. Early 20th century England became my escape from everyday traumas; solving (well, let’s be fair and say “trying to solve”) her mysteries gave me focus and something positive to look forward to.

And if my first readings were a fanboy’s frenzied attempts at armchair detection, I would return to her works again as an adult to study her, both for her brilliant plotting skills and as a chronicler of a specific time, place and attitude. Thus, And Then There Were None is a novel that I return to again and again, reveling in certain aspects which have remained etched in my mind for decades, and always finding something new to ponder. And so, if you don’t mind, let’s reflect on it together for a bit.

First let’s talk about that title . . .

The challenge for many of us who take delight in art from the past 150 years is how often we must confront the casual racism that ran rampant through popular culture. It happens to me more often than you’d think, even in my teaching. Only this morning, one of the students in my Musical Theatre class came to me with a problem: “Shakin’ the Blues Away,” an Irving Berlin song he wanted to sing, contained an offensive racial slur. We located an alternate line, but my mind raced with images of well-dressed people in a 1930’s nightclub dancing raucously to the original lyrics.

We all know that Christie was drawn to children’s literature and, in particular, nursery rhymes. The verse that inspired her original title comes from an old counting rhyme that children used (and in some cultures, evidently, still use) to learn their numbers. An interesting supposition I encountered in my research is that the term “Indians” probably came before the epithet Christie used. In 1868, a popular songwriter named Septimus Winner (“Listen to the Mockingbird”) adapted this rhyme into a song. Some of the verses varied from what we find in the novel, but the effect was essentially the same: the genocide of Native Americans had been transformed into a children’s numbers lesson. It also seems clear that the song was performed during the same time at minstrel shows, where actors sang it in blackface, which could explain how it reverted to that other word by the time Christie heard of it.

I wonder if Christie gave any thought to the potential for her original title to offend. I rather think not. It suited her purposes, both as the structure for her murderer’s plot and as a metaphor: the ten characters in her novel are bound by a certain trait, in this case a murderous past. And yet, to some degree, each is damaged by this act, disenfranchised from normal society just as the racial group represented by the title has been. One could say that U.N. Owen’s plot is a form of “genocide” against a group that he despises to an insane degree. And isn’t this the very definition of racism?

For twenty-five years, Christie’s U.S. publishers, who switched from black people to Indians, buried the offensive bits on the inside by renaming the book on the outside, nd despite robbing the mystery of one of its most significant twists, it’s not a bad title.

And yet the book I purchased in 1965 from Pocket Books was called Ten Little Indians, possibly in advance of George Pollock’s 1965 film, and it stuck on American reissues until 1986. Now we have become politically correct. Modern versions of the novel have switched to ten soldiers on Soldier Island, which is as nonsensical as it is inoffensive; indeed, being a soldier is antithetical to what these people are. But more about that later

Just what sort of mystery is it?

It is a closed circle whodunit, where a finite group of people are trapped on a remote setting and come to realize, as their number dwindles, that one amongst their own must be the killer. And yet, it is the only mystery I can think of where the entire closed circle dies. Many of you are probably aware of a 1930 GAD novel by Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning called The Invisible Host, which includes some of the same plot strands as Christie’s later novel, most significantly the use of a recorded voice to announce to the eight guests that they will soon meet the ninth member of their party – Death. Argue if you want that Bristow and Manning got there first; still, Christie’s novel is superior to its predecessor in every way.

What makes And Then There Were None most unlike a typical Christie whodunit is the way she leavens the suspicion amongst the characters. In most of her mysteries, Christie suffices with two, maybe three murders. That leaves anywhere from five to ten or so characters remaining who could have done it, and the baton of suspicion is passed carefully amongst them until Christie reveals all – including the possibility that the killer never actually handled that baton!

For a significant portion of And Then There Were None – up through Chapter Eight and just before the third death – the guests believe that the source of evil comes from the outside, from a maniac hiding somewhere on the island. Once they are forced to accept that the killer is in their midst, the characters conform to a standard GAD psychological reaction. General Macarthur dies, and they suspect the servant. By the next morning, Rogers is dead. Thus is born a new pattern: suspect a person and then (s)he dies. This lasts all the way until two are left standing.

Yet, even as the characters’ external suspicions turn from one to the other, their internal lives are operating at a different level. Each of them has been affected – hardened, weakened, or isolated – by their past crime, and the toll it takes on their emotional state affects how they come to terms with their actions before they die. Marston and Mrs. Rogers die before anyone quite realizes what is happening and thus don’t engage in this interior moral reckoning; that is the killer’s gift to them for lying at the edge of the spectrum of guilt. For the others, a different fate awaits, unique to each player in the game. Rogers is made to endure widowhood and the isolating suspicion of the others before he is hacked to death. Armstrong and Lombard become patsies, Blore dies a fool’s death, quick and violent, and Vera alternately suffers the most and receives the most autonomy over her own fate. (She could hang herself or wait for the police to arrive and hang her.) This “gift” represents Mr. Owen’s admiration of Vera as the best of her species.

It is a thriller in that, while we are interested in figuring out whodunnit, Christie provides minimal clueing, and her focus is constantly on the action of finding the killer and on the psychological effect this murderer’s game has on the players. The suspense generated here ranks at the highest level of any story Christie every wrote. Since the “detection” mostly happens by committee, complete with our understanding that one of these unofficial sleuths is, in fact, the killer, the novel never bogs down with interviews or the weighing of evidence. It moves as a thriller must move. It is full of violence. Its characters are governed more by emotion than by rational thought; indeed, one of the best elements of the novel is how Christie lets us into the thoughts of her characters, includingthe villain, as we observe everyone’s growing desperation.

It is an impossible crime mystery, like the works of Carr, Berrow, Talbot, and the like; yet, unlike these experts, Christie structures her novel so that the impossibility itself is one of the novel’s greatest surprises. Perhaps she doesn’t play quite fair in this regard because she withholds a piece of information from her readers until the penultimate chapter. However, this doesn’t spoil the book at all for us; in fact, it provides an incredible jolt when we discover, through the simple replacement of a chair, that we have been hoodwinked, and it makes us eager to discover a truth that, at least at first, the killer had no intention of revealing:

“When the sea goes down, there will come from the mainland boats and men. And they will find ten dead bodies and an unsolved problem on Indian Island.”

For someone like me, whose mind isn’t mechanical enough to figure out how a man could get shot from within a sealed hut, or killed on a sandy tennis court with no footprints around, or be attacked and killed by a flying ghost-spirit-monster, I find a delicious thrill when faced with ATTWN’s two diametrically opposed “facts”:

- The killer has to be one of the ten dead people on the island;

- The killer cannot possibly be one of the ten dead people on the island.

The guests/sleuths/victims never solve the case. The police never solve the case. Christie herself acknowledged that the only way she could paint herself out of a corner and fulfill her contract with the reader was to tack on an epilogue, a literal message in a bottle:

“It was my ambition to invent a murder mystery that no one could solve. But no artist, I now realize, can be satisfied with art alone. There is a natural craving for recognition which cannot be gainsaid. I have, let me confess it in all humility, a pitiful human wish that someone should know just how clever I have been . . . “

It is a psychological drama about the ravages of guilt. I’m not much of a fan of the inverted mystery, and thankfully Christie did not indulge in this sub-genre. However, as And Then There Were None unfolds, we become involved in not one, but nine retrospective inverted mysteries. The ravages of suspicion and fear found in a typical GAD novel are nothing to the complex feelings of terror and guilt experienced by this closed circle. Death here is punishment, and they each acknowledge that they deserve punishment. That doesn’t mean they all want to die, but the level of psychological torment here is delicious because it is built into the murderer’s plot

The killer is a master of psychology and takes into consideration the ways that fear, shock, suspicion, and self-preservation will play into the reactions of the guests. He is a self-professed sadist; he wants the guests to suffer before they die. Ironically, he is more merciful in his cause of death, taking most of his victims by surprise and ending their lives quickly. The primary issue that governs his plan is the sense of guilt that lies within his fellow guests. Those with the least amount or sense of responsibility for the death of others die first. As guilt increases, the victim suffers more, a point of importance to the killer’s plan, since the last two living souls must behave in a certain way for the plan to work.

I wonder if the naysayers – you know, those people who despise the novel, who were wandering around the blogosphere and came upon a 5,300+ word-long essay on a book they hate and thought, “Wow! This will be a fun read!” – are asking themselves if this “levels of guilt” thing really works here. Does Mr. Blore, who dies later, feel more awful about the death of Landor than General Macarthur does about sending young Richmond to his death? Does Philip Lombard, the ninth to die, feel anything about the deaths of those twenty-seven natives? And if it had been Lombard who shot Vera instead of the other way around, would he have hanged himself or been coerced into doing so by an older, frailer person?

Here’s what I think: I think that the levels of guilt come from the perspective of the killer – that he picked and chose in what order punishment should be meted out from a unique perspective based on his age, his profession, and his personality. And so, although the name of the killer does not appear until the final words of the novel, this turns out to be an inverted crime after all. Christie usually reserves her best character study for the murderers in her novels. Here we reap the benefits of everyone being a killer, so the character studies are rich, and U.N. Owen’s profile is the most fascinating of all.

Perhaps now would be the perfect time to . . .

Open the door and see all the people.

First, a few facts:

Like most of Christie’s characters, these are middle class, although three – Justice Wargrave, Dr. Armstrong, and General Macarthur – enjoy more wealth and prestige than the others. The Rogers may be servants, but as butler and cook/housekeeper, they are at the top of that heap. They are also the only suspects who are married, conveniently to each other, reinforcing the sense of emotional isolation that these people bring to this truly desolate place.

One could divide the guests into three age ranges:

- The young: Anthony Marston, Vera Claythorne, Philip Lombard

- The middle-aged: Dr. Armstrong, William Blore, Mr. and Mrs. Rogers

- The elderly: Emily Brent, General Macarthur, Justice Wargrave

Marston is significantly younger than the others and one of the few who seems to have a large circle of good friends. His is the reckless amorality of youth, and a quick exchange when he is confronted with his earlier crime is telling:

“I’ve just been thinking – John and Lucy Combes. Must have been a couple of kids I rean over near Cambridge. Beastly bad luck.”

Mr. Justice Wargrave said acidly, “ For them, or for you?”

Anthony said, “Well, I was thinking – for me – but of course, you’re right, sir, it was damned bad luck for them. Of course it was a pure accident. They rushed out of some cottage or other. I had my license endorsed for a year. Beastly nuisance.”

Notice Wargrave’s tone when he responds to Anthony: the sarcasm, the contempt for such a flippant reaction to the death of children. Dr. Armstrong is even more outraged at young men and their sports cars. At this point, Christie was about to turn fifty. She was an avid driver and a good one. I imagine she had little sympathy for Marston, but like the killer she understood that the plan to inflict suffering would be wasted on this Adonis. Marston is the first to go, and he goes quickly.

Vera and Lombard are more of an age and gravitate toward each other throughout the book, more on the basis of age than of attraction. This is significant. Every play and movie makes theirs a romantic pairing because in her play Christie saw this as the natural culmination of a happy ending. In the book, Lombard’s first opinion of Vera is that she is “quite attractive – a bit schoolmistressy perhaps . . . A cool customer, he should imagine – and one who could hold her own – in love or war. He’d rather like to take her on . . . “

Aidan Turner notwithstanding, Lombard does not take Vera on. Instead, she becomes first his confidante and then his fatal weakness: he seeks to protect her and underestimates her ruthlessness. This may help explain why Lombard gets the coveted ninth spot as victim: Owen wants Vera to be his last little soldier, and he needs to play on Lombard’s macho maleness to guide Vera to that final spot.

Vera is my favorite character in the novel, an object lesson in how well Christie manipulates us to think what she wants us to think. By allowing us regular access into Vera’s mind, we begin to empathize with her vulnerability; not until the end, however, does Christie lead us deep enough into Vera’s past to demonstrate how truly evil she was, how expertly she manipulated young Cyril to become accessory to his own murder. Her sense of abandonment by Hugo reveals her sociopathic nature, reinforced later by her expert manipulation of Lombard.

Philip Lombard is a character whom we will see often in the author’s work: the lost boy or wrong ‘un who finds some measure of heroism as a soldier and then gets lost again. From Ralph Paton to George Challenger, David Hunter to Sir George Stubbs, these men all share traits with Christie’s doomed brother Monte. They are sexually appealing, out for the main chance, sometimes redeemed but more often jailed. We can’t help but fall victim ourselves to Lombard’s charms, and for much of the novel he is the third smartest person on the island. Remember that he is the one who figures out the identity of the killer; unfortunately, he does it as part of a flirtation with Vera and promptly tosses that valuable insight away. His death fascinates because it is one of the rare cases in Christie of murder by proxy, something she will develop more deeply just a few years later, with just as fascinating results.

The characters comprising the middle-aged lot conform most specifically to various “types” often found in Christie: the bluff, hearty doctor, the stupid policeman, the dignified butler and frightened housemaid. In an early post on this blog, I pointed out the popularity of medical murderers in the canon. At least internally, Dr. Armstrong admits his culpability early on, and then he ascends to the coveted seat of “most likely suspect” due to his easy access to poisons and scalpels. His struggle to overcome his sense of guilt to minister to the dwindling party, along with his secret position of honor in the murderer’s plot, makes him a multi-faceted character – up to a point! Armstrong is Christie’s sacrificial lamb, the character we all come to suspect until that fateful, surprising moment on the beach when everything stops making sense to the survivors. It would be so easy for Armstrong to be the killer, and yet, given what we know about him and what his tormented inner thoughts reveal, it would not make any sense. The dream he has at the start of Chapter Six of the operating room and a revolving door of fellow guests/murder victims lying beneath his scalpel reveals a man who cannot make peace with the death of Louisa Mary Clees juxtaposed against his subsequent occupational success. He is the perfect victim for U.N. Owen to toy with.

The servants are the servants. Despite the fact that they fit into Owen’s plot as much as the others, Christie’s tendency to separate the classes and basically nullify servants as legitimate murder suspects causes her to limit our access to the Rogers. We barely get to know Mrs. Rogers at all, and the most we can say about the butler is that he continues to try his best to “buttle” right up to the end. Chop chop!

William Henry Blore ends up being the problem character here. All too often, the buffoon detective becomes an object of scornful humor in any detective novel, and many of the accusations Blore makes reminds us of policemen like Inspector Slack. In Christie’s play and in the 1945 film, Blore is the comic relief. (Roland Young could certainly do more than comedy – his Uriah Heep in David Copperfield is a villainous delight in false humility – but he will always be Cosmo Topper or Uncle Willie Tracy to me.) In the recent BBC mini-series, Sarah Phelps takes it in the opposite direction, portraying Blore as a closeted sadist. It is one of the most jarring changes of her adaptation.

In the book, he is one of three characters appearing “in disguise” (the other two being Lombard and the murderer), and he is lousy at it, making stupid mistakes when he poses as a wealthy South African and struggling throughout the ordeal to be the man in charge. His murder (“a big bear hugged one”) is the most awkward in the novel and becomes downright odd in the BBC version. And yet, when I directed Christie’s play and admittedly changed much of the dialogue to reflect the novel, Blore’s presence added a great dramatic dimension to the Lombard/Vera dynamic. While they all suspected Armstrong, he was the one who gave the two younger people hope for some sort of future. His death, heralded by a queer little thud in the distance that Vera mistakes for an earthquake – now the island itself is plotting against them – is more hopeful than sad because it seems proof that Armstrong is after them which gives them a certain, solid enemy and, by the way, proves their innocence. (And nobody ever much liked Mr. Blore anyway.)

The Murderer

I’ve saved the three elderly characters for last, for several reasons. Foremost is the fact that the killer resides here. If one reads carefully, none of the others could have done it. And isn’t the rendering of a final judgment usually the act of someone who possesses the experience and wisdom – even self-perceived – to judge? We’re looking here at someone who plays God, and while doctors and policemen have done so, in Christie and elsewhere, Armstrong is too craven and Blore too stupid. The idea that Lombard would waste his energy devising some self-devised moral scale and evaluating others by it, let alone playing executioner to those he finds wanting, seems completely out of character. And we know by following her more closely than any other character in the book that Vera is innocent – of these crimes, at least.

That leaves General Macarthur, Emily Brent, and Lawrence Wargrave. Despite the small matter of one being clubbed to death, another fatally injected with poison, and the third shot in the head, one of these three should be U.N. Owen.

It’s not the General. His is the most pathetic, the most humane, of backstories. He killed for love, then recognized almost immediately the consequences of his actions and suffered for the rest of his life. This is not to excuse what he did or to say he is deserving of our sympathies. Still, in a book populated essentially by monsters, we grab at whatever humanity we can find. Before he dies, the General sinks softly into madness, embracing his fate not as a punishment but as a release from it. Ironically, his untethering to reality brings to the General the first true cognizance of their dilemma, as he tells Vera:

“None of us are going to leave the island. That’s the plan. You know it, of course, perfectly. What , perhaps, you can’t understand is the relief . . . the blessed relief when you know that you’ve done with it all – that you haven’t got to carry the burden any longer. You’ll feel that too someday . . . “

This is prescient of the General, for even as Vera shrinks away in fear from the old man, she will, indeed, have the exact same experience in a couple of days, standing on a chair and placing a noose around her neck, eager to join her beloved Hugo in eternal peace.

The killer could have been Emily Brent. She is cold, ruthless, judgmental. She is not unintelligent, although her faith has narrowed, rather than widened, her insight into others. Throughout her career, Christie wrote compellingly about the lives of spinsters in 20th century life: the financial vicissitudes of Dora Bunner, the social prominence of Emily Barton and Honoria Waynflete, the good works of Miss Wetherby and Miss Hartnell, the obnoxious yet pathetic heartiness of Aimee Griffith.

Christie has shown us what spinsters are capable of, from the committing of crimes to the solving of them. They succeed at what they do by understanding and exploiting the weaknesses and follies of the world around them. Their ascent to greatness or their descent to evil depends, at least in part, on how they channel their repressed emotional lives. Miss Marple loves her hopeless nephew, gently teaches her orphaned servant girls, does good works, has a wide circle of friends, and dispenses justice with cold ruthlessness. How easy to picture Miss Brent as the Dark Marple as she twists all of that good lady’s charity into something vicious.

Which leaves only one little soldier left . . .

I remember this moment back in 1965 as if it were yesterday. Long before I ever found and read the book, our babysitter, Steve, was giving the final instalment of his oral recounting of And Then There Were None. His narrative had been lush and detailed. He took us through the ten murders and the accounting made by the police, and he left us hanging with the words of the baffled Inspector Maine: “But in that case, who killed them?” At that point, Steve paused and let the question hang in the air. It was a delicious moment and it drove me crazy. I was nine! I had no idea who the killer was. It was essentially the pilot episode of countless reading experiences I would have for the rest of my life.

Steve let that moment stretch out, a smile on his lips. And then he said: “It was the Judge.”

The oldest one. The one who dispenses justice for a living. (They even call Wargrave “the hanging judge.”) The one who manipulates the group into figuring out that the killer was one of them, raising the aura of fear and driving them to do desperate things. The smartest one. Really the one most likely to have done it. An old trick of Christie’s, it turns out, but played so well here. She employs some of her favorite bluffs. First, she pushes the notion of Wargrave as the killer by having Lombard making a rational aargument for his guilt. We see this dangling of rightful suspicion quite often in the canon, and it has the effect, even on the most hardened Christie fan, of dispelling suspicion.

The second trick is to seemingly eliminate the murderer from suspicion with a certain finality. This is usually accomplished by providing them with a perfect alibi that is sprung at a crucial moment, either early on or after an arrest. Here the author audaciously “bumps off” her suspect, leaving it up to the reader to suss out how this might be connected to the “red herring” mentioned in the next stanza of the rhyme.

The third and best bluff of all is how Christie can offer a killer’s words and thoughts and manipulate us into misinterpreting them. This can be seen from the very opening of the novel. Justice Wargrave opens and closes the book – first suspect/victim and murderer. He is sitting in a train carriage, pondering all that lies before him. Like the other guests, most of this will take the form of a reminiscence over the invitation received to Soldier Island. Wargrave even has a letter, which he draws from his pocket, from an old friend.

“Mr. Justice Wargrave cast back in his mind to remember when exactly he had last seen Lady Constance Culmington. It must be seven – no, eight years ago. She had then been going to Italy to bask in the sun and to be at one with Nature and the contadini. Later, he had heard, she had proceeded to Syria where she proposed to bask in yet stronger sun and live at one with Nature and the Bedouin.”

Look at what Christie does here: In one brief, highly humorous paragraph, she brings an aristocratic eccentric to life with such authority that we must believe in Lady Constance (whom we will all be rather disappointed not to meet) . . . and in her letter.

“Contance Culmington, he reflected to himself, was exactly the sort of woman who would by and island and surround herself with mystery! Nodding his head in gentle approval of his logic, Mr. Justice Wargrave allowed his head to nod . . . He slept . . . “

“In gentle approval of his logic?” What could logic have to do with any of this?

Oh, the cleverness of Constance Culmington. Oh, the genius of Agatha Christie.

An excellent discussion, Brad. I agree with you that this one is several sorts of novels all in one, you might say. And it certainly calls into question the belief that many have had that Christie was ‘all plot, no character.’ For me, anyway, it’s the characters that make this as deep and memorable as it is. Yes, the plot’s ingenious and the solution is, too. Yet, its equal (greater? Up to you to decide) strength lies in the way Christie explores the characters’ psychology, and how that is impacted by the situation in which they find themselves. More than that, she explores the psychology that drove these characters to act as they did in the first place. On that score alone, it’s a fascinating story. And, from what I read, one of the ones she personally liked best.

LikeLiked by 1 person

She was certainly proud of the reception it got because she claims she worked harder on this one than on most! It shows in every seamless corner! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Enjoyed this, Brad – and what fabulous book covers!

LikeLike

Thank you, Chrissie! Hope to see you within the next 365 days!

LikeLike

Likewise, Brad!

LikeLike

Since you mentioned the Invisible Host: The movie version is under the title “The Ninth Guest” on Youtube, for everyone who’s interested.

I watched it, it’s entertaining and one can’t deny the parallels, especially in the first half. But I agree that Christie’s version is much better done, especially regarding the ending (including the choice of the killer).

And I can’t speak about the book, since I haven’t read it. But at least in the movie there are a bunch of servants trapped with the eight guests. They are neither killer, not victims nor serious suspects at any point, and one of them clearly serves as comic relief. Both tonally as well as logically these characters didn’t make sense at all.

And (slight spoiler): When the survivors are escaping the place in the end, the servants aren’t mentioned and probably stay behind in the deadly trap, with nobody caring (unless I missed something. English isn’t my mothertongue, so it’s certainly possible, but I don’t think so).

And now I’ll continue reading your review. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I guess that ties in nicely with my last post about servants! I do like the movie, and I acknowledge that Bristow did it before Christie . . . but she certainly didn’t do it better.

LikeLike

Yeah, at least Mr and Mrs Rogers served a purpose. They are probably the worst written of the ten characters. I don’t think many readers every seriously suspected them and IMO even Hugo, who only appeared in Vera’s thoughts, had more depth. But they basically had the same function for the plot as the other victims. And at least the other characters suspected Rogers instead of acting like he isn’t there.

LikeLike

I just realised that this is a german movie poster for the Russian film. Meaning a german dub must exist and I never heard about it. Hopefully I can find it. Thanks for that picture!

LikeLike

Thanks, Brad, for a fascinating and thorough critique.

The reader has been racing through a thriller counting down the victims until there are just two, and the Vera saves herself, so is she the killer? Oh, she’s hanged herself – that’s odd – and then things slow down as two policeman calmly discuss what has happened, there’s only a few pages left and now you’re telling me the whole thing is impossible???

At this point has anyone ever sat back and thought the whole thing through? I very much doubt it!! Although can you imagine a Challenge to the Reader being inserted here?

Turning the page it is quickly apparent that it is the judge and yet the how is still kept until the final page.

Looking forward to your big 100th anniversary piece next year!

LikeLike

Oh, John, you know me so well! October, 2020 . . .

LikeLike

And how seriously did they suspect him? One out of three of the victims had been poisoned, and they still wanted him to serve them lunch.

LikeLike

“Gumnaam, containing one of my favorite song sequences in all of Bollywood, ”

It is also shown in the opening credits of the film Ghost World

It is also used in the 2011 Heineken commercial The Date

LikeLike

I saw the recent theatrical adaptation when it was on tour, and it was actually pretty good IMHO. Like the other versions referred to above it came close to restoring the original ending, the only difference being that the killer reappeared at the end just before Vera’s suicide (which we didn’t actually see, leaving the possibility that she changed her mind…) I thought Paul Nicholas was excellent as the judge (for non-UK readers, he’s best known for the Cockney character Vince in the romantic sitcom Just Good Friends, and also had a few top ten hits in the 1970s).

LikeLiked by 1 person

A first-rate discussion, Brad. Very interesting indeed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Martin! 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: #592: Reflections on Detection – The Knox Decalogue 1: The Criminal | The Invisible Event

My first Christie too, after watching the 1948 movie as a wee bairn, so about 1969 or 1970.

As you say, it’s all been downhill since.

LikeLike

Pingback: LET’S FACE THE MUSIC AND RANK: My Top Ten Christies | ahsweetmysteryblog

Pingback: A CENTURY OF AGATHA CHRISTIE, PART TWO: The Glittering 1930’s | ahsweetmysteryblog

Pingback: ” . . . CRACK’D FROM SIDE TO SIDE”: Madness in Christie | Ah Sweet Mystery!

I’ve often wondered if this might have been an even better book without the confession in the bottle at the end. Brad, you very astutely point out the one clue which, if noticed, will definitively point the reader to the solution, namely an unusual turn of phrase in the judge’s thoughts that makes very little sense unless he is the killer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Michael, I do believe that mystery writers enter into an unseen contract with their readers to answer the questions posed in the text. I can’t imagine the outrage that people would have felt if they never learned the identity of U.N. Owen; however, I do believe that if Christie had gone there, she wouldn’t be read by half as many people who read her today. Even though it’s not a traditional whodunit like she had been writing for the past twenty years, Christie set up a situation that begged an answer. I think she came up with the best answer. Is the “message in a bottle” a bit clunky? Sure. Perhaps she could have just provided an epilogue narrated by the murderer. But I’m not going to quibble . . .

LikeLike

Yes, you make a good point that Christie’s readers want and expect a denouement where the mystery is fully explained. I think to have left it unsolved at the end (as a kind of challenge to readers to solve it themselves using the clues provided) might have made an interesting book, but probably a far less enjoyable and popular one. I’m in the middle of an Agatha Christie re-read at the moment and am really enjoying your blog and the other GAD blogs you have linked to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope you’ll come by and leave

Comments as you hit this or that book. If you’re reading them chronologically and are about to hit the 40’s, there’s so much to talk about!

LikeLike

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX (The Blog-iography!) | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Oh, Brad! (May I call you Brad?) There is sooooo much I could/want to say about this book and all the various adaptations. But I’ve already said a bunch of crap on your blog so I will content myself with a comment about the title.

My understanding was that the original N-word in the title referred to people of the Indian subcontinent in Southeast Asia. And some stuff was changed around in the text to first make it refer to a person of African ancestry and then to a person of Native American ancestry and then we get the soldiers. Have you heard this? Or is it something I made up myself? (That happens sometimes.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Julie, my understanding is that the word stems from the Latin (one n in the middle) for “black,” and while it was ostensibly meant to be used in a neutral way, slave traders and owners used it in a patronizing way. The important fact is that by 1939, it was a racist epithet, and Christie’s casual use of it (because of the children’s rhyme that contained the word and centered the plot) is troublesome. And the U.S. saw the problem immediately and never published it under that name. (Of course, we’re no better when you think of how we appropriated the word “Indian!)

And you can call me Brad and dump as much “crap” as you want here! I love it all!!

LikeLike

“one n in the middle” ? It should be “one g in the middle” .

LikeLike

Pingback: “WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM MY FRIENDS . . . ” An Agatha Christie Starter Kit | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: “I’ve got a little list . . . ” Part II: Ten Favorite Mysteries of the 1930’s | Ah Sweet Mystery!