“Hamilton Burger arose ponderously to his feet. ‘Just a moment, Your Honor’, he said. ‘I’d like to be heard on that question. I believe there has been a very deliberate attempt on the part of someone, and I am not at the present time naming that someone, although I hope to be able to do so, before this case is concluded – I think there has been a very deliberate attempt on the part of someone to tamper with the evidence in this case.’”

Three guesses as to the identity of that “someone” . . .

There seems to be a consensus that later Perry Mason books aren’t as strong as early ones. Based on my reading of 1954’s The Case of the Restless Redhead, I think that I can definitely state that . . . well, I’m not sure. I will say that Mason here seems older, slicker, more at ease with himself. As D.A. Burger complains above, Mason plays fast and loose with the rules – here he wrecks the ballistic evidence in a blatantly illegal way and just sits back, calmly assured that the police and prosecution will run with it in all the wrong directions, all but cinching an acquittal for his client. Della Street is still staunchly at Perry’s side (Paul Drake has almost nothing to do in this one, alas), but their relationship is all professional. She even nags him to answer his mail!

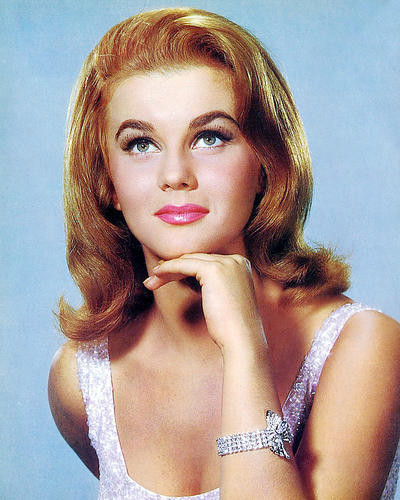

As for the restless redhead herself, well . . . she’s a more interesting character than the borrowed brunette was and probably on par with the black-eyed blonde. Evelyn Bagby has always wanted to make it in L.A., to have the Hollywood studios recognize her acting talent. But on the road to achieving her dreams, she has run into one nasty obstacle after another. The worst is a con artist named Staunton Vester Gladden (oh, how I love your names, Mr. Gardner!) who promised Evelyn her own key to the star dressing room and then took her for a ride:

“He gave me a ninety-day course. By the time he had finished, I had lost a lot of things. I’d picked up some polish and a lot of wisdom. He had absconded with all of my little inheritance, and I was flat broke, disillusioned, and had to take a job as waitress.”

Evelyn struggles to pick herself up and try again, but on the way to Los Angeles her old car breaks down in Corona, and Evelyn winds up involved with Hollywood royalty: gorgeous actress Helene Chaney, on the way to Las Vegas to marry for the third time, has stopped at a Corona motel to connect with her maid-of-honor, Irene Keith. Irene is carrying all the jewels that Helene will wear at the wedding, but they are stolen out of her car. And then a witness steps forward who claims he saw Evelyn Bagby exploring the trunk of that car . . .

Restless Redhead begins cleverly in medias res with Perry driving to Riverside for a meeting with one Judge Dillard, only to find His Honor presiding over Evelyn’s trial on larceny charges. Unfortunately for the defendant, her court-appointed attorney is very wet behind the ears. But young Frank Neely is about to have a stroke of good luck in the form of a tutorial on cross-examination by Perry Mason. His mentoring of young Neely throughout is my favorite part of the novel; once Evelyn is accused of murder, Neely returns to help Mason with her defense, and the veteran instructs the neophyte in the ways of an expert attorney’s courtroom strategy:

“’Make an objection once in a while, Neely. Let them know you’re in the case.’

“’I’m afraid to,’ Neely whispered. ‘I might be objecting to the wrong thing. You’ve got that prosecutor so puzzled now he doesn’t know just where you’re going to make your fight.’

“’Object to anything,’ Mason said, ‘just so it isn’t important. Let them get in all the important facts whether they hurt us or not. Save your objections for the facts we already know. Throw a little variety into the case and give him something to think about. After all, your girl(friend) is watching you back there in the courtroom, and the newspaper men are taking this stuff down.’”

Nobody will argue that the Perry Mason books aren’t formulaic. That may have something to do with the fact that Erle Stanley Gardner employed plot wheels to provide the slight variations to each of his novels. To all intents and purposes, it works for me: the problems his clients bring Mason are varied enough to focus on different points of law and provide different types of drama. Sometimes there’s more Della than Paul, and sometimes it’s vice versa. Sometimes we get Sergeant Holcomb and sometimes we get Lieutenant Tragg. In the books, the District Attorney employs multiple ADAs to try Mason’s clients, and these young men tend to blur in their overweening zeal to show up and/or bring down the greatest defense attorney of them all. And in the end, Mason wins. Always. All the time.

What never seems to vary is that Perry Mason stands at the center of it all, from page 1 to page 200, and hanging out with him is always, for me, a pleasure. Funny story: I decided to look up “Frank Neely” to see if he appears in any future cases. A lot of reviews of The Case of the Restless Redhead came up, including a 2016 review from my friend Kate Jackson of Cross-examining Crime. Unfortunately, Kate didn’t get along with this book, finding the courtroom scenes dry as dust. She asked for feedback as to other people’s experience, and among the comments was one wet-behind-the-ears blogger who talked about how much better the TV series was than the books.

Today, I hang my head in shame for having made that remark. My comments were based on not having read a Perry Mason novel for many years, and let me say here that this know-it-all knew nothing when it comes to Perry Mason. My great fondness for the series has been tempered by several years of getting reacquainted with Erle Stanley Gardner, and I never stop marveling how a man so prolific could be so consistently entertaining.

And because the plot wheel is ever-spinning, it is hard for me to make a generalization about the quality of older Mason novels vs. newer ones. Restless Redhead has a strong beginning and that wonderful subplot of Mason mentoring Frank. Irene Keith, Helene Chaney, and Helene’s fiancé Mervyn Aldrich (a particularly obnoxious specimen whom you can’t wait to see Mason bring down) are better suspects than the characters in Borrowed Brunette but not quite as good as those in Black-Eyed Blonde. There’s much more time spent in court here than in the other two novels I’ve covered, and while poor Kate found this part of the book tedious, I lapped it up.

The trouble here is two-fold. First, all of Evelyn’s troubles hinge on a coincidence involving her old nemesis Mr. Gladden that is really hard to swallow. And then there’s the solution, which truly comes out of nowhere. Oh, it was clear from the start that more than one person was out to get Evelyn. But in the end this conspiracy involves a lot of people who are completely extraneous to the text we’ve been following. Two of them don’t appear until the penultimate chapter, where another conspirator is mentioned for the first time (and it’s someone we never meet!) And as clever as Mason is in defending his client, his summation of the facts behind the murder comes out of nowhere. The concept of fair play aside – and Gardner wasn’t really an author of traditional whodunnits – any general sense of fairness to the reader goes right out the window here.

That said, The Case of the Restless Redhead is fast-paced and entertaining. And “The Case of the Restless Redhead,” which first aired on September 21, 1957 and has the great distinction of being the debut episode of Perry Mason, makes for a great introduction to the series. We meet Perry (Raymond Burr looks especially tousled and handsome in these early episodes), sitting at home reading law books for fun; Della makes her entrance popping into the office at 1am with a helpful thermos of coffee; and Paul Drake is introduced at a poker game which he grumpily interrupts to check a gun’s serial number (the same number, I might add, as the murder weapon in the novel!) We even get a rare glimpse of Sergeant Holcomb, who looks like he would make a slimy adversary for Mason – except he’s dropped, as in the books, in favor of Lieutenant Tragg, who runs the investigation here. The great Ray Collins receives his own dramatic entrance, banging on Mason’s door in the middle of the night in search of the murder suspect he is sure the attorney is hiding.

Up to a point, the episode provides a well-condensed version of the novel, but it also establishes the pattern each episode of the series will follow. The victim’s rank behavior toward Evelyn is evident in the book, but here other characters have also fallen victim to his schemes and now have stronger motives. One of the best book suspects is cut out altogether, the conspiracy that ruffled my feathers in the book is dropped, and the murderer is given a whole new occupation and backstory that sets them up nicely to deliver the dramatic courtroom confession that will become a trademark of the series.

The most dramatic bits from the novel are preserved: we actually get to see Evelyn attacked in her car, and most of the ballistic brouhaha in the trial is preserved. I couldn’t help wondering, however, if a certain change here made a legal difference: in the book, Holcomb pushes past Mason, removes a pistol from his car, and basically perjures himself in order to look like a competent policeman. In the episode, however, Lieutenant Tragg asks Mason for the murder weapon and Mason hands a gun to Tragg. To my mind, this would imply that Mason was representing the gun he handed over as the murder weapon, even though he knew it wasn’t. (Clearly, I should’ve gone to law school, as my momma dearly hoped I would.) Still, this is an excellent start to a series that will captivate audiences for ten years and expand “Perry Mason” into a household name. And if the novel represents how “bad” some people feel the later Mason books got, then all I can do is heave a sigh of relief at how much I enjoyed it. Now I can explore those titles from the 50’s and 60’s with more confidence.

This ends my present mini-series about Perry Mason and his dames. But I have one more Mason up my sleeve to wrap up this year – one of those hot titles from the 1930’s coming at you in December!

I think Lucy was the only one of your choices that was not a natural redhead … which is my way of saying I’ve not read the book 😆

LikeLiked by 1 person

No pic of Rita Hayworth? Maybe she wasn’t a natural redhead, but she sure had a restless life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I actually had a picture of Rita, but I ran out of space, and as I contemplated moving all the other pics around, I just didn’t think this was a good enough snap of her to include it.

LikeLike

I loved Mason’s mentorial inclinations and thought the better of him for it, particularly when he shoves his young study in the limelight. It’s a great bit, and I always imagined it reflected the author’s own leanings.

“Lieutenant Tragg asks Mason for the murder weapon and Mason hands a gun to Tragg” while reminding him that the gun may not be evidence of anything, He never identifies the gun as “the murder weapon” and in fact, tries to warn Tragg off of the assumption that the gun is the murder weapon. No reason not to hand the gun over, Tragg had a warrant, unlike Sgt. Holcom’s completely unconstitutional search and seizure in the book.

A very good mystery overall. I love Gardner’s pace, his ability to draw a character sharply, dialogue and most of all, his clever understanding of the law and trials, particularly.’

I thought the story was a good, solid launching point for the tv series, but I was a bit peeved at the rewrites.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I tell you, this deep dive into the Mason oeuvre is wreaking havoc on my long-standing love of the series. Obviously, every adaptation here has to simplify the book’s plot and make it adhere to the series formula. At best, the series is showing me how much ESG liked to play with his own formulae and how many of the books simply cannot translate well into a fifty-two minute “Law and Order”-style template.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agree! The series didn’t do most of the stories justice. If you want to read a good one, try the Bigamous Spouse.

LikeLike

Pingback: THE ERLE STANLEY GARDNER INDEX | Ah Sweet Mystery!