A Caribbean Mystery doesn’t get enough love. I am here to rectify that.

It merits barely a mention in the various Christie biographies. Robert Barnard, in A Talent to Deceive, dismisses the book as “in the tradition of all those package-tour mysteries written by indigent crime writers who have to capitalize on their meager holidays.” Even my go-to guide, Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks is disappointing: Dr. John Curran spends most of the section devoted to this title discussing plot ideas that Christie discarded, particularly the one about a twisted woman who kills anyone who expresses happiness. (It’s an idea that reminds me quite a bit of a certain late Poirot!)

Curran concludes that the notes reveal how “the fertility of Christie’s imagination” might have resulted in “a very different novel from the one we have.” Barnard is more overtly critical: “Nothing much of interest, but useful for illustrating the ‘fluffification’ of Miss Marple.” That process began with The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side, a book I accused of suffering from bloat and an increasingly wandering authorial mind. But that is not what we get with A Caribbean Mystery. I wouldn’t go so far as to argue that this constitutes A-list Miss Marple, but it has much to recommend it, including arguably the last great clue Miss Marple created during her career. And while Christie’s rendition of the Caribbean setting may be problematical, despite her recent trip to Barbados, placing Miss Marple in a tropical setting sets off a chain reaction that transforms our heroine, fluffy though she may be, into something mythical. And like the best myths, this one is a multi-parter, as the notion of Dark Marple, the personification of Nemesis, will return.

I offer a personal note by way of explanation for my defense of this book. A Caribbean Mystery was the first Miss Marple novel I read. After I cut my teeth on And Then There Were None, I returned to the pharmacy where many paperback copies of Christie’s books resided and purchased Murder on the Orient Express and Three Blind Mice, and Other Stories. The first introduced me to Hercule Poirot, and with the short story “Strange Jest” I met Miss Jane Marple. I liked the lady immediately in the four collected tales I read, and my next trip to the drugstore resulted in my buying the book we’re discussing now.

You always remember your first.

* * * * *

The Hook

“Like to see the picture of a murderer?”

The opening of A Caribbean Mystery is as concise as The Mirror Crack’d was meandering. It feels lighter in tone, which costs us that emotional richness that was the best part of the earlier book, but which serves this story better.

We still begin on Page One with Miss Marple, only this time she is not alone. Old Major Palgrave is regaling her with his many stories, and the creative spark this ignites in the narrative is classic Christie. In her boredom, Miss Marple’s mind wanders, allowing her to fill us in on the exposition needed to explain her presence in, for her, such an unusual place and to fill us in on Miss Marple in general. Remember – this was the first novel of hers that I read, and yet, due to Christie’s masterful choosing of facts, Miss Marple emerges as the same recognizable character she must have been to readers who had followed her exploits since 1928. The fluffy exterior belying the sharp mind; her natural insights into people, her ability to deal with characters in difficult situations – all of this is here! (We get much more than that, which I will discuss later.)

But no matter how sharp she is, Miss Marple is bored by Major Palgrave – and that makes for a novel! She’s not listening clearly to his ramblings or taking them seriously enough. As he searches through his stuffed wallet for the picture of a murderer, she assumes everything he says is a little suspect:

“(The photos) we’re part of the Major’s stock-in-trade. It illustrated his repertoire of stories. The story he had just told, or so she suspected, had not been originally like that – it had been worked up a good deal in repeated telling.”

This is certainly what Christie wants us to believe. She employs a stock character – the boring military man – that she has utilized throughout her career; most of these men exist in the books as social scenery. And in the tendency Miss Marple sometimes has to make a mistake early on (see The Murder at the Vicarage and The Mirror Crack’d), she buys into Christie’s cliché. She doesn’t denigrate Major Palgrave, but she is bored and vaguely irritated by him.

We readers are much more observant: we perk up at the story of the killer, and “super” fans make note of Palgrave’s throwaway line as he’s looking for the picture and comes upon another. “Forgotten all about that business. Good-looking woman she was, you’d never suspect – “ What a lovely way to spread the suspicion and fool the reader into thinking he’s ahead of Miss Marple herself. Of course, like the sleuth we forget all about the clue that is presented on Page One and is literally staring us in the face throughout. (Another benefit of Miss Marple’s wandering mind!)

By the end of Chapter Two, we have met all the significant players, gotten Miss Marple’s initial impressions of them (partly by using village parallels, which are not helpful at all in this case), gotten the slyest of whiffs that all is not right with Molly Ralston – and set the stage for murder.

Score: 8/10

The Closed Circle: Who, What, When, Where, Why?

Who?

“The reflections on Anglo-Indian colonels show how little she felt she had to change her stereotypes to bring them up to date.” (A Talent to Deceive, p. 189)

Major Palgrave provides Robert Barnard with an opportunity to take a dig at Christie. So I hope you won’t think me perverse if I take a little time to give the character his due. Of course, Major Palgrave is a stereotype. That’s precisely the point here.

“. . . although he was the victim, it was one of those rare cases where a greater knowledge of the victim does not help you or lead you in any way to his murderer. The point, it seemed to (Miss Marple), and the sole point, was that Major Palgrave talked too much!”

But that doesn’t mean that Christie ignores the social status of men like Palgrave, especially in a later book where her own age weighs informs at least some of what she writes:

“The pattern was essentially the same. An elderly man who needed a listener so that he could, in memory, relive days in which he had been happy. Days when his back had been straight, his eyesight keen, his hearing acute. Some of these talkers had been handsome soldierly old boys, some again had been regrettably unattractive; and Major Palgrave, purple of face, with a glass eye, and the general appearance of a stuffed frog, belonged in the latter category.”

Once he dies, amidst the “sunshine, seas and social pleasures” of St. Honore, he is quickly forgotten. But not by Christie, who creates a poignant portrait of a lonely man who derived pleasure from the company of others, even if it cast him as an old bore. And not by Miss Marple:

“. . . (Major Palgrave) represented a kind of life that she knew. As one grew older, one got more and more into the habit of listening; listening, possibly without any great interest, but there had been between her and the Major a gentle give-and-take of two old people. It had had a cheerful, human quality. She did not actually mourn Major Palgrave, but she missed him.”

For the most part, the rest of the cast is perfectly serviceable, a bit shallow but never dull. Molly Kendall, Lucky Dyson, and Esther Walters are blond and pretty; Evelyn Hillingdon is dark and weather-beaten. Lucky is presented as a sort of femme fatale, almost certainly a murderess herself, and so her murder causes no real feeling. (The bit about Lucky admiring Molly’s scarf is nicely woven into the early narrative. Never take anything Christie writes for granted!) Certainly we feel bad for Molly’s predicament, which at the age of thirteen I did not recognize as a parallel to the women in Palgrave’s story. Lucky has standard genre secrets, but Evelyn and Esther are more layered; both have hidden depths that serve the mystery. We feel for Esther – her final confession of love is sadly pathetic – and I’m glad that Christie let us know Esther’s fate in the book’s sequel.

The men feel more like pieces moved around to serve the plot: dark and charming Tim Kendal, dark and quiet Edward Hillingdon, bluff and hearty Greg Dyson, and the silent, good-looking Jackson. The first three are types who have all been Christie killers before; here, they share the typical story arc of surface happiness giving way to darker feelings. And while Jackson’s purpose for being there doesn’t arrive until the end, Christie has fun with him. He’s so good looking that even Miss Marple sits up and takes notice. (And Mr. Rafiel seems awfully eager for his daily massage!) Meanwhile, Jackson occupies a precarious position in the social scheme of things, as Tim Kendal points out to Miss Marple: he isn’t quite a servant, but he doesn’t have the social cachet of even Esther Walters. As a result, one might assume that, on this island, Jackson is a lonely man.

I’ve saved the worst and best for last. Christie demonstrated in Hickory Dickory Death a limited understanding for – or a refusal to create – the multi-dimensional characterizations to which people of differing cultures are entitled. I’m not going to belabor this because, in all fairness, the tourists and servants who populate the book are filtered through Miss Marple’s perceptions, and these are strictly limited. Still, it’s annoying to see that Victoria Johnson and all her fellow native citizens are characterized primarily by non-human imagery (“a magnificent creature with a torso of black marble”) and the size and brightness of their teeth. She’s cunning rather than bright, and it signals her sacrifice to Second Victimhood. The only other character of color is the beautiful Señora de Caspearo, who despises ugliness (“Oh, how ugly are old men! Oh, how they are ugly! They should all be put to death at forty, or perhaps thirty-five would be better. Yes?”) Her presence amounts to little more than a cameo, but at least she is given the responsibility of waving The Major Clue around like a flag for Miss Marple and the reader’s benefit.

Christie has brought rich old men to life before, most of them benevolent if prickly gentlemen (Lord Caterham, Rufus Van Aldin, Conway Jefferson), and a few of them difficult to monstrous (Simeon Lee, Timothy Abernethy). Mr. Jason Rafiel, supermarket magnate, is the most complex of the lot: difficult and fine, sickly and powerful.

“Mr. Rafiel, in beach attire, was incredibly desiccated, his bones draped with festoons of dry skin. Though looking like a man on the point of death, . . . sharp blue eyes appeared out of his wrinkled cheeks, and his principal pleasure in life was denying robustly anything that anyone else said.”

His relationship with Miss Marple is in marked contrast to the one she had with Major Palgrave because circumstances make it dynamic. Miss Marple bestows upon him the ultimate mark of friendship by relying on him for help. And in Mr. Rafiel’s mind, Miss Marple transforms from one among the multitudes of old hens who come to the tropics and get underfoot into the goddess Nemesis. This relationship forms the heart of the novel, and Christie capitalizes on it by bringing Mr. Rafiel back for Miss Marple’s grand finale in Nemesis.

What?

“Miss Marple lay thinking soberly and constructively of murder, and what, if her suspicions were correct, she could do about it. It wasn’t going to be easy. She had one weapon and one weapon only – and that was conversation.’”

Major Palgrave has told Miss Marple a story about a serial wife murderer. (He has also mentioned two other murder cases in passing – the notorious affair involving Harry Western and the one about a good-looking woman or, as related to Mr. Rafiel, a modern Lucrezia Borgia). The wife murder tale is by far the most dynamic, but even though this was only my fourth Christie, I thought myself pretty clever to not exclude the others. In short, I was thinking exactly what the author wanted me to think.

The body of The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side is flabby. Here the investigation is lean and efficient and, best of all, it is guided from start to finish by Miss Marple. This time, it’s the police who enter halfway through the proceedings in order to investigate Victoria’s murder. Miss Marple disappears for two short chapters (Fourteen and Fifteen), and then we’re back with her on the beach or the patio or anywhere she can engage with members of the closed circle or gossip with Joan Prescott, the Canon’s sister. And while one might expect the “interrogations” to be fluffy like Miss Marple’s head and slow to get to the point, Christie uses these chats to both move the plot along and deepen character.

The degenerative nature of Molly’s mental health plays out pretty organically. I’ll admit that I was thirteen when I first read this novel, but I certainly didn’t recognize in Molly’s behavior the pattern described in the Major’s story. It’s Molly who discovers Victoria, and the question arises as to whether she might have killed the girl herself. I think this helps obfuscate the pattern by making us take our observances in the wrong direction.

We learn about the complicated relationships between the Dysons and the Hillingdons, one couple awful and the other sympathetic. They are tied together by shared scientific interests, but as we learn more about their personal lives, Christie dangles the possibility that either Greg or Lucky is the person in the Major’s picture. Greg’s first wife died, and it seems clear that Lucky killed her in order to marry Greg – and that she used the besotted Edward as a patsy to access the drugs she needed to do the job. But it’s also possible that Greg is the wife murderer – although a clever reader will note that the pattern of his wife’s death does not fit the story. It may not be the most original plotting, but these are red herrings, and they are developed enough to keep readers guessing.

While there are three murders in this book – and we all know how Christie and her fellow GAD writers used extra murders to goose the narrative – this time the other deaths are beautifully handled and integral to the plot. Victoria Johnson’s sharp observation about the Serenite bottle (it wasn’t there before!) opens up the case by giving Dr. Graham second thoughts about the state of Major Palgrave’s health. And the third death serves two purposes, both as a plot point and as an example of Christie-an morality. Plus, it makes for a brilliantly dramatic scene. Everyone thinks that Molly’s madness has finally resulted in her death on the beach, and they all go off to find the authorities, leaving Miss Marple and Evelyn Hillingdon alone with the body.

“The moon had been behind a cloud, but now it came out into the open. It shone with a luminous silvery brightness on Molly’s outspread hair . . .

“Miss Marple gave a sudden ejaculation. She bent down, peering, then stretched out her hand and touched the golden head. She spoke to Evelyn Hillingdon, and her voice sounded quite different.

“’I think,’ she said, ‘that we had better make sure.’

“Evelyn Hillingdon stared at her in astonishment.

“’But you yourself told Tim we mustn’t touch anything.’

“’I know. But the moon wasn’t out. I hadn’t seen – ‘

“Her finger pointed. Then, very gently, she touched the blonde hair and part of it so that the roots were exposed . . .

“Evelyn gave a sharp ejaculation.

“’Lucky!’”

It’s a wonderful moment – and it is quickly followed by the full birth of Miss-Marple-as-Nemesis, as she employs Mr. Rafiel and Jackson to save a life. There’s no need for fake fishbones or throwing voices or faking a blackmail attempt: Lucky’s murder-by-accident has made the killer desperate, and the climax of the novel becomes a thrilling race against time.

When and where?

“Lovely and warm, yes – and so good for her rheumatism – and beautiful scenery, though, perhaps – a trifle, monotonous? So many palm trees. Everything the same every day – never anything happening. Not like St. Mary Mead, where something was always happening ”

Miss Marple is on vacation, the first time that we have seen her in foreign climes. Her reflections while she basks in the sunshine of St. Honore are less poignant, more judgmental and much funnier than we saw in The Mirror Crack’d. It’s as if her creator is also taking a break from the darker tone that underscored her post-war novels, particularly the Marples. The portrait of tourism we get here hearkens back to 1941’s Evil Under the Sun, but they are definitely the impressions of an elderly British lady rather than the more cosmopolitan thoughts of Poirot.

As one might expect, some of these observations are problematic in these modern times. Oh, she’s game to try the native foods – no bread-and-butter pudding for her! And her dislike of the loud steel drums seems so natural it reminds me of my own grandmother and her distaste for rock ‘n roll! Miss Marple enjoys the hard work of the staff and the exotic dancing of the entertainers – but there’s a faintly patronizing tone to her admiration. The servers in the restaurant, “tall black girls of proud carriage, dressed in crisp white” are all efficient,

“. . . but there was an experienced Italian headwaiter in charge, and a French wine waiter, and there was the attentive eye of Tim Kendal watching over everything . . .”

More interesting is the fact that, in finding herself far away from St. Mary Mead, Miss Marple feels that her understanding of people has been out of whack:

“Up to now, she had missed what she usually found so easily – points of resemblance in the people she met to various people known to her personally. She had, possibly, been dazzled by the gay clothes and the exotic coloring; but soon, she felt, she would be able to make some interesting comparisons.”

When she does begin to do her thing, however, she limits her analysis to her fellow Europeans – and really only to those from the British Isles and America. I’m not accusing Miss Marple of anything here; this is the natural behavior for a British colonialist. But because she is not the well-traveled woman that her creator was, and Christie chooses to view St. Honore through Miss Marple’s eyes, we get a very limited view of this exotic place. The setting serves its purpose, but it never comes to vivid life on the page. And Christie, who could have included a more multi-cultural array of major characters, chooses not to do so. I’m not surprised to find this in Christie, whose early travels emphasized British colonies. But one can’t help thinking that, in terms of place and the closed circle, an opportunity was missed.

Score: 6/10

The Solution and How She Gets There (10 points)

“But yes – I tell you it is unlucky here. I knew it from the first – That old Major, the ugly one – he had the Evil Eye – you remember? His eyes, they crossed. It is bad, that!”

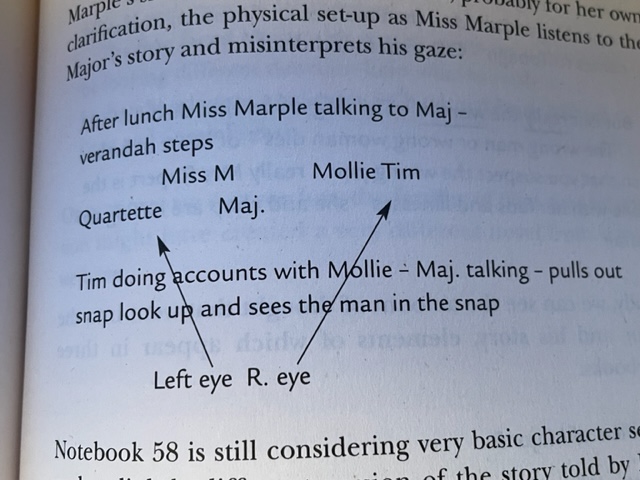

On the beach, Señora de Caspearo gets to give the whole game away as she complains to Miss Marple that the island is an unlucky place, and the Major its evil minion. She tells of making the Sign of the Horns when the Major looked at her, although “since he is cross-eyed, I am not always sure when he does look my way – “ In her notes for A Caribbean Mystery, Christie included a rudimentary sketch of the scene at the beginning and where each character sat in the Major’s false and true eyelines.

It’s really as simple as that: only Tim Kendal is sitting where the Major can see him with his one good eye. Tim Kendal, whose wife is displaying exactly the behavior of all the previous victims of the man in the picture. I’m sure if one catches this clue and/or recognizes the pattern early on, the book is much less enjoyable for that reader. But those of us who study Christie recognize the quality of her books when re-reading them with the solution under our belts is just as enjoyable as it was the first time. And here the journey Miss Marple takes to reach the truth is half the fun.

In Chapter 16, “Miss Marple Seeks Assistance,” she realizes that with time to solve the case running short (vacations are finite affairs!), she needs help.

“She realized, bitterly, that here on this paradise of an island, she had none of her usual allies . . . Sir Henry Clithering – always willing to listen indulgently – his godson Dermot, who in spite of his increased status at Scotland Yard was still ready to believe that when Miss Marple voiced an opinion, there was usually something behind it.

It is at this moment that Mr. Rafiel demands her presence. He is aware of the atmosphere in the place and the gossip flying around on the beach, and he, too wants to investigate. And so a new partnership is born between a man with the status to find out what is needed and a woman with the perceptive powers to analyze the information received. In that way, Mr. Rafiel fulfills the function of the policemen in other cases who respect Miss Marple enough to fill in the blanks in her portfolio of information.

I love how the case is solved by two old people with time on their hands who, although they are worlds apart in personality and life experience, find a deep bond through their shared investigation. Mr. Rafiel comes to the island every year ostensibly to rest and relax, and yet rest and relaxation are anathema to him. “There’s not very much to do out here except make money,” he tells Miss Marple, but even that comes so easy to him that he needs more “entertainment” to challenge his wits. And so he decides to help Miss Marple go after the killer.

Mr. Rafiel’s crabby personality is the perfect foil to Miss Marple’s. He’s so above the fray (“I don’t tell stories!”) that he needs her to lay out her case. And yet he is a smart old cuss and cuts right to the chase:

“There’s something wrong here. The motive’s inadequate . . . Anybody would laugh at such a story. Here’s an old booby telling a story about another story somebody told him, and showing a snapshot, and all of it centering around a murder which had taken place years ago! How on earth can that worry the man in question?”

This is an excellent question, and Miss Marple deduces the perfect answer: the killer intends to strike again. This should take us right to Greg Dyson, whose wife died before, and Lucky’s death a few chapters later would seal the deal for the most inexperienced of Christie readers. (Personally, I was holding out for a female killer!) Ultimately, the Evil Eye of Major Palgrave – a fabulous clue in a series of books that rarely provides them – sets the matter straight, and the pharmaceutical information that Jackson conveniently provides in the eleventh hour seals the deal.

Score: 7/10

The Marple Factor

I’ll be honest: after initiating myself into the Marple-verse with A Caribbean Mystery, I was often puzzled at how little she appeared in my subsequent readings. Here we get all Marple all the time! What’s more, this is Jane Marple as we have never seen her before: the stakes are high as ever, but she does not have the ear of the police. In fact, she has broken trust with the only person whose ear she did have – Dr. Graham, to whom she must admit she lied about the photograph of “her nephew.” Thus, we get a rare inside glimpse into the workings of Miss Marple’s professional mind because here she is on her own:

“Old ladies were given to a good deal of rambling conversation. People were bored by this, but certainly did not suspect them of ulterior motives. It would not be a case of asking direct questions. (Indeed, she would’ve found it difficult to know what questions to ask!) It would be a question of finding out a little more about certain people.”

This is a succinct explanation of what separates Miss Marple from a policeman or private detective. She has her own way of speaking, and it often involves assessing the personality of whomever she is conversing with. Thus, she can be direct with Mr. Rafiel and Joan Prescott but must don the mask of a fluffy old lady with most of the others. And she understands – as we witness through her interactions with the doctor – when she must switch tactics and assess the potential loss from such maneuvers. And, as always, Miss Marple recognizes her own limitations and seeks out help when it is necessary.

Christie also provides us with a fine interior portrait of Miss Marple as foreign traveler, and here it couldn’t be clearer that the author is not speaking through her character. Although her psychological acumen is top-notch, she has never professed to be a woman of the world, and it shows in her limited world-view. Yes, she knows about “queers” and people of color, but she isn’t especially enlightened about them. Some of the opinions she expresses here are difficult to embrace in these modern times, but they humanize her exactly at the right time: the moment she takes on the super-human identity of Nemesis.

I may have a twinkle in my eye as I write this. Suffice it to say that Miss Marple is great here.

Score: 10/10

The Wow Factor

The case presented here is perfectly fine. If you have read your Christie before coming here, you could easily spot the villain early on. If not, I think you have a good read before you. (That is why I would put this book on the list of possible “First Christies” to recommend to friends.)

It is the only time we see Miss Marple overseas. Evidently, she was considered for the leading role in Death on the Nile, but it was not to be. It is the birth of Nemesis, although Miss Marple had already played that role to perfection in A Pocketful of Rye. And it introduces Mr. Rafiel, who serves as a magnificent foil to Miss Marple and will provide the starting point for her final adventure. (That leads to a little problem in the timeline, but we’ll tackle that when we get to it.)

Thus, the case itself may not provide much of a wow factor, but all the accoutrements surrounding our heroine are pretty special.

Score: 6/10

FINAL SCORE FOR A CARIBBEAN MYSTERY: 37/50

(Note: With this score, A Caribbean Mystery comes in at a tie with The Moving Finger. These books top each other in different respects. Caribbean is such a wonderful and rare example of putting Miss Marple front and center, while she barely makes it into Finger. And yet the earlier book, in terms of character, place, and plot, is richer through and through. And, despite a twenty-one year gap in publication dates, they both have “stuck in their time” weaknesses, in terms of anti-Semitism (Finger) and race (Caribbean). The “Cinderella” make-over for Meghan Hunter is problematic, but I have to say I was recently pleasantly swayed by Laura Thompson’s argument on the podcast Tea and Murder that Meghan’s joyful acceptance of Jerry’s offer to travel to London, the plain fact that she wants to grow up and to look the part, somewhat mitigates its “ick” factor.

Ultimately, even though there is a paucity of Miss Marple in Lymstock, The Moving Finger is simply a better written novel that stays with me longer and merits more frequent revisits. Thus, as you will see at the end of this year-long ride, I place it ahead of A Caribbean Mystery.

We all have our “special” favourites, and I suspects I would give it a lower overall score in context but I think you are being pretty thorough in your reasoning here Brad! Glad it stands up – always a nice feeling, that 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

For a minute there, I thought I had gotten the eye wrong in my trivia question – which would, of course, have voided our draft and made us have to do it all over again. And I’m ninety-five percent sure the second draft wouldn’t be identical to the first!

LikeLiked by 1 person

😜

LikeLike

I continue to enjoy your chronological review of the Marple books.

While anyone who has read the book knows why an eyeball would be included in the cover artwork, can I say that second cover with the eyeball staring down at the disembodied head is just plain terrifying 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think both the eyeball covers are profoundly disturbing. One can only hope that Major Palgrave’s was a better fit. If not, it explains Miss Marple’s retreat into flights of fancy while he yammered on.

LikeLike

One of my top three Miss Marples.

LikeLike

I thought it was very problematic that Miss Marple apparently flew to St. Honoré and that Inch doesn’t drive a Tesla. Very “stuck in it’s time”, wouldn’t you agree? (*Sarcasm mode off*)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am so glad someone other than myself loves this story. I don’t understand why it isn’t a top fave for everyone. Christie literally tells you in the first 10 minutes what is going to happen. Then, it happens right under the viewer’s nose. She Penn and Tellered her audience before those two even were born. LOL This alone makes Marple in the Caribbean a total treat.

Her killer was another one of those in a long list of charmers who turn out to be deadly dangerous. They all give me the creeps, which is another reason I really like this story.

The curmudgeonly Mr. Rafiel (who later “appears” in a fashion in Nemesis) is a bit stereotyped, but a rather familiar character for Christie. I compare him to Luther Crackenthorpe (masterfully played by Maurice Denham in the teleplay 4:50 From Paddington) constantly complaining and expecting to be waited on. Miss Marple always knows just how to deal with such gentlemen.

It’s a good read and I always loved playing the teleplay for friends and family, hoping they would recognize the pattern described by the old Major at the start of ACB.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yup, there is little more satisfying than when an author bamboozles you! Christie did it to me a lot; so did Christianna Brand, who was especially clever at slipping something in at the top that makes you smack your head when you get to the end. This is the sort of thing that I’m frankly NOT finding in all the Bushes/Loracs/Flynns, etc. who are being rediscovered these days. Maybe I’m too old and clever, or too impatient or something. But I’m open to suggestions for books or authors who can accomplish this same feat!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: RANKING MARPLE: Settling the Scores | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX (The Blog-iography!) | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Talking about The moving finger, the girl in the book that miss marple reads in the beginning of A Caribbean Mystery somehow always makes me think of Meghan… is that just me. I really like Caribbean, much more than finger, probably because i saw it in the Joan Hickson series when I was quite young, and it helped forming my interest in Agatha Christies works.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love both of them! I don’t really see Megan in that girl from the book, except that both of them project a sort of “sad sack” air. We barely see that fictional character, but I’m certain that Megan has a sharper mind and MUCH better hygiene!!

LikeLike