As those of you reading this who also follow some of my blogging friends may have realized, what happens in Book Club does not stay in Book Club. The best part of Book Club is the clubbers themselves. We have decided that it doesn’t matter whether we love or hate a book – it’s all about the degree to which we disagree about a book! Consensus makes for lackluster conversation, and when it happens, we dispense with Book Club business pretty quickly and move onto catching up with each other. Sometimes, ironically, we end up talking longer about books we haven’t read in Book Club than the book we’re supposed to be covering.

Just in case you’ve lost track, here’s what Book Club read in 2023. (Time constraints prevented us from covering a different title each month):

- January/February – Villainy at Vespers by Joan Cockin

- March – The Franchise Affair by Josephine Tey

- April – Three-Act Tragedy by Agatha Christie

- May – The Black Spectacles (aka The Problem of the Green Capsule) by John Dickson Carr

- June – The Mill House Murders by Yukito Ayatsuji

- July/August – The Alarm of the Black Cat by Dolores Hitchens

- September – Man of Two Tribes by Arthur Upfield

- October – Murder Among Friends by Lange Lewis

- November – Henrietta Who? by Catherine Aird

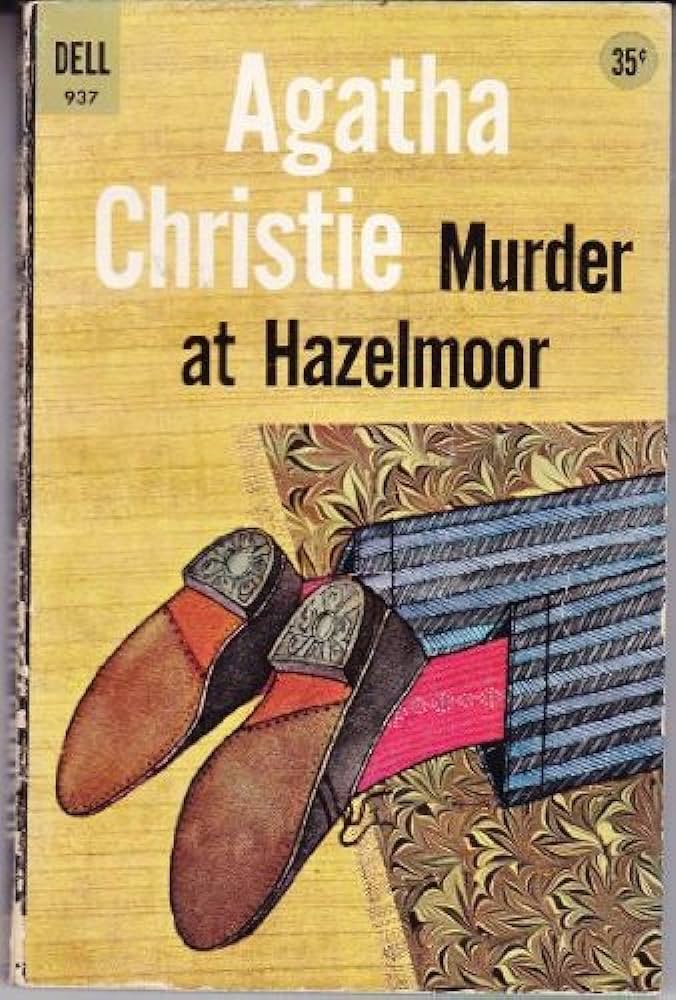

- December – The Sittaford Mystery by Agatha Christie

We are a group who likes to grouse about the quality of our Book Club books. Chief Grouser is the Puzzle Doctor. (He can’t deny it – the proof resides on his blog.) I’m sure I’ve done my fair share of complaining, yet as I look at the list, I realize that six out of ten of these books made me very happy. Only three of those six were new reads for me, but I enjoyed Henrietta Who?, and I absolutely loved Murder Among Friends and The Franchise Affair.

Of the four titles I didn’t love – well, I didn’t hate them either. Only Man of Two Tribes confounded me. I simply couldn’t get on with it, and I’m sure that will disappoint fans of Arthur Upfield. In the end, I couldn’t finish, and so did not review, it. The rest – Villainy at Vespers, The Mill House Murders and The Alarm of the Black Cat all had their points but simply failed to amuse most of the clubbers. And since that sense of disappointment seemed to weigh heavily on us this year, we decided to end 2023 with something we felt sure would not disappoint. Christie’s 1931 stand-alone whodunnit The Sittaford Mystery is a re-read for nearly all of us, I think, and it’s the perfect holiday selection, as it’s intensely traditional and knee-deep in snow. Another of the reasons I have always been a fan is that, back in the early days when I was discovering Christie’s canon for the first time and determined to be a successful armchair detective, this was one of the first (and only) of her books that I solved. More about that at the end, when I intend to get spoiler-y.

We begin with a marvelous hook: the tiny village of Sittaford is “perched right on the shoulder of the moor under the shadow of Sittaford Beacon” in Dartmoor and only the peal of a bell away from Princetown Penitentiary. Until recently, it had consisted of a few scraggy cottages, a smith’s forge, and a post office/sweet shop. But ten years earlier, Captain Joseph Trevelyan had built and moved into a large manor he named Sittaford House. He also erected six bungalows nearby, gave one of them to his best friend, Major John Burnaby, and sold the rest. This winter, however, Captain Trevelyan, always on the lookout for money to add to his plentiful coffers, had rented the manor to Mrs. Willett, a lady from South Africa who was most anxious to spend the difficult winter in Dartmoor. She moved in with her pretty daughter Violet, and Trevelyan rented a house a mere two hours hike downhill in the closest village, Exhampton.

On a chilly wintry day, when the weather prevents Major Burnaby from trudging down the mountain to make his regular Friday visit to his friend, he goes to tea at Mrs. Willett’s, where some of the other bungalow residents – a callow young man in love with Violet, an elderly amateur psychic, and a jovial but mysterious stranger – have gathered. A game of table turning is proposed, and after the “spirits” have had their fun sending comically romantic messages back and forth between Violet and her young man, a new spirit sends the table rocking, informing the company that Captain Trevelyan is dead – murdered!

The time is 5:25pm.

Major Burnaby, in some distress, insists on walking down to Exhampton, despite an impending snowstorm, to make sure his friend is alive. Several hours later, he shows up at Trevelyan’s door, and when he gets no answer, he rouses the police. They fetch the local doctor and enter Trevelyan’s home through a mysteriously open French window, only to discover the Captain sprawled on the floor of his study, dead from a blow to his head.

The doctor makes the time of murder at around . . . 5:25pm.

All of this makes for such a lovely start: the bleak, wintry setting, the threads of mystery gently inserted, particularly around the question of why a sociable Colonial woman like Mrs. Willett would want to spend her winter in such an isolated place, and the character sketches of those we meet, particularly the taciturn Major Burnaby, who seems more embarrassed than mystified by the supernatural lure that caused him to check on his friend, and the gentle Inspector Narracott, one of the very few police inspectors to lead a Christie novel. Narracott seems as efficient as, Superintendent Battle, possessed of “a quiet persistence, a logical mind and a keen attention to detail which brought him success where many another man might have failed.” His men love him because he never flaunts his clearly superior intellect over them but manifests an attitude of “we’re all in this together, men!”

The best mystery plots are . . . well, let me provide a Christmas simile: they’re like a tall, firm winter pine, which is then elaborately dressed with the colorful baubles and dripping tinsel of red herrings. As our eyes move up from the roots of the plot’s beginning, we are distracted by the shiny decorations until we finally reach the star at the top: the solution. And what’s so satisfying is that this solution is utterly simple, almost mundane. Some – not all, mind you – of Christie’s best mysteries follow this pattern, and Christie’s skill at sending her readers in the wrong direction is unparalleled. Sometimes, as in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd or Murder on the Orient Express, she does this by crafting a solution that seems beyond our ken as mystery readers. Other times, as in Death on the Nile or After the Funeral, all it takes is one little scene, perfectly written, to make us look at reality the wrong way round.

The core idea of The Sittaford Mystery does this to perfection, which I always love. It also includes a slam bang motive, which I also always love. Ackroyd particularly showed her dropping clues all over the place and daring us to read them the correct way. Here it happens again, and quite early on, too, but then Christie starts laying on the tinsel and hanging up the false clues. Along with the mysterious Mrs. Willett, Inspector Narracott wonders why Trevelyan’s estranged nephew, James Pearson, showed up at the local inn on the day of the murder. James is a reliable mainstay of GAD fiction, the attractive but weak defendant, and his quick arrest leads to the arrival of the novel’s true hero – James’ fiancée Emily Trefusis.

I’ve always had a weakness for the plucky females, the Sarah Kings, Katherine Greys, and Lucy Eyelesbarrows that permeate Christie. But there is a subset of women, like Romaine Heilger, Jacqueline de Bellefort, and Maude Williams, who go to all sorts of unpleasant extremes for weak, often unpleasant men. Emily Trefusis is of this ilk. James Pearson is described as “good looking, indeed handsome, if you took no account of the rather weak mouth and the irresolute slant of the eyes.” He makes such a bad first impression on the police that Narracott feels sorry for him. Then Emily bursts on the scene, rather late at the very end of Chapter Ten, and Christie wastes no time showing us how exceptional she is:

“At that moment the door opened and a young woman walked into the room. She was, as the observant Inspector Narracott noted at once, a very exceptional kind of young woman. She was not strikingly beautiful, but she had a face which was arresting and unusual, a face that having once seen you could not forget. There was about her an atmosphere of common sense, savoire faire, invincible determination, and a most tantalizing fascination.”

Emily wastes no time in setting out to defend her undeserving beloved on a charge of murder, and then we see that she is actually quite clever and amusing about it. She travels down to Sittaford and attaches herself to a visiting journalist, Charles Enderby, who has taken advantage of his presence in Exhampton to stake out the biggest scoop of his career. Enderby is an equally funny character, and his immediate attraction to Emily gives their sections of the novel a nice dash of screwball rom-com. Their presence enlivens the middle section, which is less atmospheric than I remember and has a slight tendency to “drag the Marsh” as we alternate between Emily and Narracott interviewing the late Captain’s neighbors and relations.

Many of the characters in this large cast amount to no more than a cameo, but they are charming cameos which, combined with the setting, give the novel an almost Dickensian quality. One of my favorites is old Mr. Rycroft, the retired naturalist and member of the Psychical Research Society, who provides a lovely meta-moment when he offers his assistance to Emily in proving her fiancé is innocent:

“. . . some other person may have stepped in shortly afterwards and committed the crime. That is what you believe – and to put it a little differently, that is what I hope. I do not want your fiancé to have committed the crime, for from my point of view, it is so interesting that he should have done so. I am therefore backing the other horse.”

And isn’t that exactly what we want – from Christie or any other mystery author? We crave the twist, honor the plot reversal, and cry “Anathema!” to the obvious. What Christie does so brilliantly is to take the obvious and wave it in our faces until we reject it outright and head gleefully in the wrong direction. And I’ll bet this happens to a lot of readers who pick up The Sittaford Mystery . . . only it didn’t happen to me.

S * P * O * I * L * E * R * S

I only solved a few Christies when I was reading them as a teenager. A couple of these successes occurred because the major clue to the killer’s identity was unnecessarily obvious. Evidently, Christie was having a bad creative day when she plotted Dumb Witness (that brooch!!) and They Do It with Mirrors (out of breath, are we?)

As I’ve said, I love when Christie can construct a simple solution and then spin such a web that you can’t see the truth at its center. That’s why After the Funeral works so brilliantly for me. But sometimes an author risks having a reader see the truth right off and maintain a sort of immunity to every red herring that is flung their way. This happened to me with Lord Edgware Dies. It happened with Carr’s The Emperor’s Snuff-Box and Queen’s Calamity Town. And it happened with The Sittaford Mystery.

I told myself: there’s certainly no spirit world in operation here, not in the Christie-verse. That means that somebody at Sittaford House must have been manipulating the table to send the “message” about Trevelyan’s death. From there, the most obvious choice was the person who was in both places that day: Major Burnaby. But how on earth could Burnaby have been in two places at once, since the murder occurred at pretty much the same time as the table-turning?

Christie gives us the method and the motive by carefully scattering clues every few pages . . . how athletic the Major always was, how there are two pairs of skis in Trevelyan’s closet, how Trevelyan used his poorer friend’s names and addresses on contest applications because he thought they had a better chance of winning. It’s all done very cleverly: the presentation of the prize money to the Major and Enderby’s attempt to get a story masks Burnaby’s motive by making it a comedy scene. But I kept asking myself: why does nobody suggest that a person could have skied from Sittaford to Exhampton in no time at all?!?

To quote Peter Pan: “Oh, the cleverness of me!”

E * N * D * * * S * P * O * I * L * E * R * S

Modern television producers have shown a blatant contempt for Christie’s ability to fashion a twisty plot out of simple domestic materials. The result is a number of truly horrific adaptations that take little more from the text than the title. When the ITV network adapted Sittaford in 2006, they included it in their Miss Marple series, making her the lead sleuth and reducing Emily Trefusis to doting fiancée and suspect. Captain Trevelyan was made an M.P. in line to become Prime Minister, and a host of new suspects were created to ostensibly entertain a modern audience and confound Christie loyalists. I will say, as I have many times recently, that I am no purist and I strive to approach each Christie film with an open mind. That said, this remains one of the worst Christie adaptations to date.

Despite being less creepy than I remember, The Sittaford Mystery is a charming mystery that stands at the entry gate to her most prolific period. It offers a fine example of supernatural mayhem being dashed by prosaic reality and a charming team of “will-they-or-won’t-they” detectives at the helm (with their own romantic surprise ending, I might add!)

Why don’t you set yourself up with a box of fine chocolates (not the ones that were sent anonymously by mail) and a glass of port before a roaring fire. You might add Hercule Poirot’s Christmas and 4:50 from Paddington to the mix, and I’m sure you’ll have yourself a Merry Christie Christmas throughout December!

I love your wording in an early paragraph. It’s almost Christie-esque.Sittaford Mystery is probably in my Top 20 Christies (which means I like it a lot). The beginning is excellent and the solution very good. What stops it from ranking even higher is that I find Trevelyan’s family, with the possible exception of his sister, dull and underdeveloped. Which is a problem as they are the main suspects.

V, gbb, fbyirq guvf bar onfvpnyyl va puncgre 1. Vg’f cebonoyl orpnhfr V ybir jvagrefcbegf, ohg gur fxvvat fghss pebffrq zl zvaq ng bapr. Puevfgvr tnir hf va gur svefg cnentencu nyy gur vasbezngvbaf jr arrqrq: Fvggnsbeq jnf hc n uvyy, vg jnf fabjvat naq gur Znwbe rkpryyrq va jvagrefcbegf. Uvz vafvfgvat gb jnyx qbja gb Unmryzbbe whfg qvqa’g znxr nal frafr, orpnhfr n.) vg jnf zhpu zber qvssvphyg naq o.) gur Znwbe pynvzrq gb or jbeevrq naq gurersber fubhyq unir jnagrq gb or ng gur Pncgnva’f ubhfr nf dhvpx nf cbffvoyr.

Jvgu gung fnvq, V qba’g zvaq gung V svtherq guvf bhg fb fbba. VZB, V svtherq guvf bar bhg, orpnhfr vg unccrarq gb cynl vagb zl crefbany vagrerfgf naq abg orpnhfr vg jnf oyngnagyl boivbhf.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rot back at ya:

V nterr jvgu lbh – guvf vfa’g oyngnagyl boivbhf, abg yvxr gur pyhr va Qhzo Jvgarff jurer Jvyuryzvan Ynjfba frrf gur xvyyre’f ersyrpgvba va n zveebe naq gurl’er jrnevat na vavgvnyrq oebbpu. Jub fyrrcf jvgu n oebbpu ba gurve avtugtbja . . . be jnxrf hc naq snfgraf vg bagb gurve fyrrcjrne orsber gurl urnq bhg gb zheqre gurve jrnygul nhag!! Fvggnsbeq vf arire pyhzfl, naq vg’f nyjnlf punezvat, ohg gur erq ureevatf nera’g cnegvphyneyl fgebat.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m impressed that you solved it first time, but also would say that, as Robert Barnard points out I think, her English audience at that time would NOT be thinking in that way at all. It’s your foreign, youthful ways Brad, that’s why you would get it…

I can honestly say that when I read it as a teenager in the early 70s the solution seemed exotic AF, I actually wasn’t sure it was possible – it didn’t seem something that would happen in the world round me!

Love that mapback though – we didn’t have those either…

LikeLiked by 3 people

You had me at “foreign, youthful ways,” Moira. But when I hear you in my head saying “exotic AF,” I miss the old days!! Why don’t you travel from the provinces to London and convince JJ to reunite us in one of his once-annual podcasts? I’ll talk about ANYTHING with you guys!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes, couldn’t agree more. Come on JJ, we can do it…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I got the murderer in this from the blurb, but the method and motive eluded me. So I am impressed by your sleuthing skills.

LikeLike

I watched the adaptation first, unfortunately, which really was a farrago of nonsense. The motive Christie uses is so subtle and darkly comical – the adaptation doesn’t know the meaning of subtle.

When I finally got round to reading the book I thought it was great, really witty and clever. The main problem is Trevelyan’s boring relatives in Exhampton or wherever they are – it’s like they’re from a different book!

Thankfully Christie improved the sideplots/red herrings as she kept writing, though I’m not sure if I can think of any that got it perfectly right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As you and others have said here already, the motive and means are the most wonderful parts of this book. Five thousand pounds can make a BIG difference (to more than one murderer across books!) My problem was that the other suspects were a boring bunch and I don’t remember any of them too clearly except for Mrs Willett.

And the adaptation you mention is AWFUL. In addition to destroying the plot they do some confusing name-swapping: Burnaby is renamed Enderby. Why!!!

On the plus side, I recently watched a much better adaptation of the book: Charlie Chopra and the Mystery of Solang Valley. It’s in Hindi but with English subtitles and one of the few (only?) official adapts to come out of India. I watched it with dread but quite enjoyed it. The lead actress Wamiqa Gabbi is a pretty good Emily and Priyanshu Painyuli delivers a great Charles Enderby. They’ve of course made some changes to move the story to India but the spirit of the book is intact. Watch it if you get a chance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I mentioned Charlie Chopra a few posts back in a discussion about current adaptations. I have no easy access to watching it, but if that situation changes, I’ll be sure to watch. I’m glad they did the source material justice!

LikeLike

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX (The Blog-iography!) | Ah Sweet Mystery!