Let me be among the first to wish a happy thirtieth anniversary to one of our most beloved small presses, Crippen & Landru. Founded in 1994 by author and scholar Douglas Greene and his wife Sandi, and named after two of the most deliciously infamous murderers in history, C&L has spotlighted the best in short crime fiction from authors both classic and contemporary.

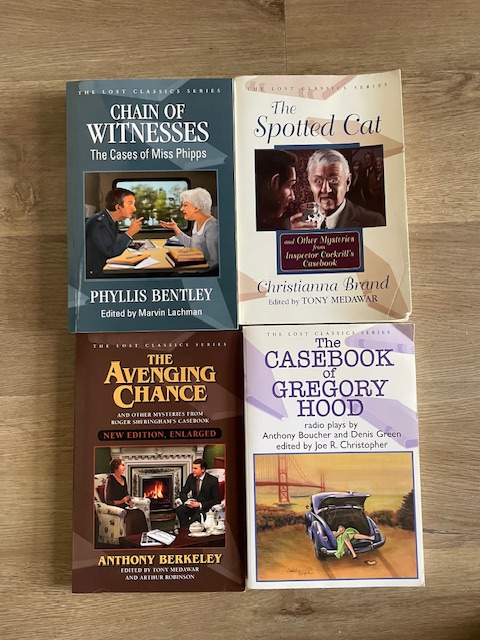

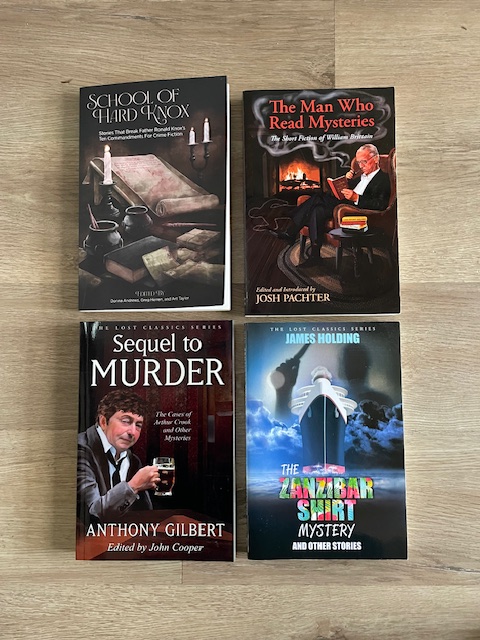

This Golden Age aficionado is particularly grateful for the many rare or lost works by GAD authors published under C&L’s Lost Classics series. My passion for old radio mystery series has been fed by collections of scripts by Ellery Queen (The Adventure of the Murdered Moths), John Dickson Carr (The Island of Coffins, Speak of the Devil, 13 to the Gallows) and The Casebook of Gregory Hood (written by Anthony Boucher and Denis Green when their Sherlock Holmes series took a summer vacation!) I’ve also had the opportunity to dive into the short fiction of favorite novelists like Christianna Brand, Anthony Berkeley, Helen McCloy, and Patrick Quentin and to walk down memory lane from the days when I subscribed to Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and looked forward to the latest stories by Phyllis Bentley, William Brittain or Edward D. Hoch.

In 2018, Greene passed the publishing reins over to fellow writer/scholar Jeffrey Marks and assumed the position of Senior Editor, ensuring that C&L’s work would continue for a long time to come. And now Jeffrey has offered those of us who have reaped the bounty of these collections a chance to join the celebration by highlighting one of C&L’s nearly 140 books. I chose one that straddles the realms between classic detective fiction history and contemporary writing.

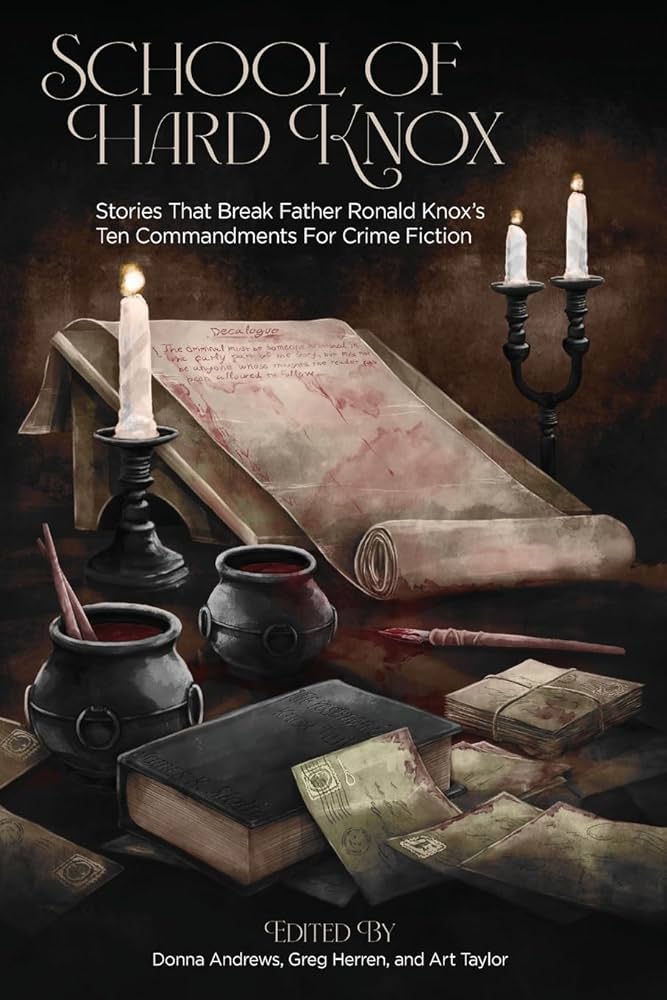

The School of Hard Knox, edited by Donna Andrews, Greg Herron and Art Taylor, gathers fifteen writers together to pay homage to theologian and author Ronald Knox (1888 – 1957). In the midst of his distinguished scholarly career, Knox managed to write six mystery novels and three short stories. But where Knox really made his mark with GAD enthusiasts was in the creation of a Decalogue of Rules, also known as The Ten Commandments for Detective Novelists, which no less august an institution than The Detection Club adopted as its oath of initiation for membership. While they may be slightly tongue-in-cheek, the Commandments provide intriguing insight into the early history of classic crime fiction, as Marks explains in an introduction that lays out the reasoning behind each rule.

Each modern author was invited to select one or more of Knox’s rules and, well, break them in a story of their own. Marks has even invited readers to play along with the game by trying to guess which rule(s) will be broken in each tale and to send their “solutions” to this question to the publisher. I’m not sure that this game is still going on, but Jeff mentioned prizes, so, if you want to go for the gold, you should read the book and send in your answers before you read my review! I will tell you this from my own experience reading the stories: it’s not easy!

Of course, the answer seems to stare you in the face with the title of the first story, “Not Another Secret Passage Story,”by Donna Andrews. This short-short tale, really more of an amuse bouche, manages to cram a murder and a centuries-old treasure hunt into its few pages, but all of that is outdone by the lovely play on words that closes the story.

The second story, Frankie Bailey’s “Matter of Trust,” is more substantial but also very much a modern crime drama rather than a classic mystery, despite it’s being set around the holidays in 1948. There’s an interesting dual narrative going on, which Bailey merges together by the end, but the beats of the story have been dramatized in so many modern cop shows that there’s very little here that will surprise you. And I’m darned if I can figure out which of Knox’ rules this one violates – a problem that will continue to haunt me throughout the collection!

The fraught dinner party has been a staple setting of mysteries since I don’t know when. How many times have thirteen people sat down to a sumptuous feast – and only twelve arise from the table at meal’s end? “The Dinner Party” by Nikki Dolson offers a distinctly modern take on the idea. Teresa is Black, gorgeous, a young widow whose precarious financial situation has forced her into employment for a mob boss. Her job is to collect debts, and she is supported (and guarded) by a handsome giant named Clayton. Their latest job is to replace the mob boss and his wife as guests at a posh dinner party in the desert outside Las Vegas in order to collect a debt from one of the guests. A violent rainstorm strands everyone together; a murder is committed, and Teresa switches roles from collector to detective.

This is the longest story in the book, and it meandered too much for my taste. The murder happens quite late, and the detection doesn’t amount to much. I could hazard a guess as to which of Knox’s rules is violated here, but it is more by process of elimination. However, I like Teresa and Clayton, and there’s a little sting at the end that makes me think this pair belongs in a longer book with a better developed plot.

Author/Anthologist Martin Edwards knows something himself about what makes a good short story, and his contribution here, “The Intruder,” sharply sets the parameters for a pithy inverted story from the very beginning: “Peering through the trees, Gough watches his wife ring another man’s doorbell.” Gough is a respectable shlub, a park ranger who has managed to snag a beautiful wife ten years his junior. You can’t help but sympathize with the guy when he suspects his wife of infidelity, but at the same time there’s something a little off about him, an impression confirmed when he decides to do away with his wife’s lover. It’s not till the final line that the Knox Connection becomes clear, but it packs a sweet wallop.

The Commandments served as a warning to authors to avoid tired cliches (no twins! No secret panels!) and as a manual toward maintaining a pact of “fair play” with all the armchair detectives who bought their books. Of course, great authors like Christie and Carr managed to break a rule or two and still play fair or, at least, come up with something fresh and exciting. One rule is especially tricky, however, because breaking it tends to push a story out of the mystery genre entirely. That’s what happens with “The Ditch” by Greg Herron, which starts out in a YA Hardy Boys vein (the teenaged narrator is reading The Secret of the Lost Tunnel in bed when the story begins) and escalates into something out of a Vault of Horror comic book. It’s suspensefully written and good, gory fun – but is it a mystery story? What I will say here is that Herron does a great job exposing the different kinds of horror that can pervade the lives of young people.

In 2004 author Naomi Hirahara began a series of seven novels featuring Mas Arai, a survivor of Hiroshima who has moved to Pasadena and become a gardener. Haunted by his past, Mas Arai landscapes the homes of wealthy Angelenos, has a stormy relationship with his daughter Mari – and solves mysteries. The series ended in 2018, but Hirahara has resurrected her taciturn gardener in the short story, “Dichondra.” Now 82, he is pressed into service once again at the behest of his daughter and son-in-law to work for a Mark Zuckerberg-type billionaire who has recently installed a Japanese garden on his estate and wants to consult Mas Arai on its cultural accuracy.

Murder ensues, and Mas Arai literally has his moment in the sun, assisted by the billionaire’s devoted housekeeper, Rebeca Garcia. It’s a beautifully written but slight tale, with too quick and expected an ending, but it serves as a great inducement to further explore Mas Arai’s world.

At first glance, no predilection of the modern mystery author seems to fly in the face of the sense of “fair play” than the all-too-common trope of the “unreliable narrator.” Knox’s first rule includes the idea that the murderer “must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to follow,” while Rules 8 and 9 concern the detective and the Watson (often the narrator) concealing facts from the reader. Of course, seasoned fans know the delicious thrill when an ace author plays fair despite breaking the rules! (See that novel by Agatha Christie, or read any footnote in a John Dickson Carr book where the author swears the reader is not being lied to!) But those were the days when mysteries were clued. The modern unreliable narrator is just that, a liar whose lying lies are exposed in the end. There’s rarely anything “fair play” about their deception – but this is not to say there’s nothing clever or fun about how the presentation of “the world as it appears to be” is transformed into the world as it truly is.

Which brings us to Toni L.P. Kelner’s “Baby Trap.” It begins with one of those online entreaties we tend to read in horrified fascination, drawn to how some people endure lives of unrelenting drama. A young woman asks for advice to protect herself from her horrific mother-in-law, known as “The Harridan,” who once accused the girl of trapping her son into marriage through pregnancy and, now that her son has tragically died, wants the baby for herself. What follows is an entertaining tale where, from the start, you can tell that something is up. It twists and turns and makes very clever use of its title to bring about a satisfying conclusion – but, in the end, is it a crime story at all?

Given the distinctly modern bent of this collection, it’s nice to finally come upon a no-holds-barred homage to the Golden Age with “The Stolen Tent” by Richie Narvaez. Set during wartime aboard the Dittbrenner, a dirigible bound across stormy skies for Lakehurst, New Jersey (a poor choice of destination, I must say!), we find the great Puerto Rican detective Balthazar Miró, assisted by that self-centered gourmand of a Frenchman, Doctor Dusfrene, investigating the locked-room death of the obese manufacturer, Hugo Alvedine. With only fifty-six passengers, forty-one crew members and a stowaway aboard, this is a true closed-circle mystery!! It’s also more parody than pastiche, and before that twist of a finale, Narvaez manages to break at least a half dozen of Knox’s Commandments.

Commandment #2 states, “All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.” To my mind, this means that anything having to do with the crime in a mystery must be explained by natural means. The séance announcing a murder, the weapon floating in air, the monster flying through the sky . . . all of these must by story’s end have a rational explanation. On the other hand, if you are attempting to mix genres (i.e., mystery with horror or mystery with science fiction), it’s only fair that readers ust be made cognizant ahead of the solution of any special abilities of, say, werewolves or alien technology that might be significant to finding the solution.

Still, I don’t see how this Rule of Knox’s has any bearing on the nature of the detective in a story. Charles Todd’s Inspector Rutledge works with a ghost (maybe it’s in his head, but the ghost helps solve cases); Sookie Stackhouse works with vampires, werewolves and a host of other spooky critters. So what if your sleuth is a vampire or an alien . . . or a three-foot tall French gargoyle named Dorian Robert-Houdin who fancies himself a modern-day Hercule Poirot (they both possess “little grey cells” – Dorian’s are literally grey!) Gigi Pandian has written seven novels about Dorian and his friends as they solve impossible crimes, and for this collection, she has produced her first short story about the stony sleuth, “The Rose City Vampire.”

The city of Portland is agog with the news that high-powered attorney Melissa Babcock has been attacked in her bedroom by a vampire. She awakened with oozing fang marks on her neck, and both she and her son saw the blood-sucker floating outside her window. Panic has set in, to the point that the vampire himself has written a letter to the editor stating that he means no harm to anyone with a pure heart! Can Dorian solve the problem of the vampire before anyone is seriously hurt or killed?

The explanation of how the vampire moves in and out of a solidly protected mansion and then “floats” outside Melissa’s window is clever and rooted in the logic of the real world, So cudos to Pandian for that. However, I don’t buy that the culprit would resort to this plan or that sophisticated Portlandians would respond as they do – except, perhaps, in a world where gargoyle detectives exist. And unless we’re counting the presence of a living gargoyle as la règle enfreinte, I fail to see what commandment has been broken here.

I have this same problem at the end of “Chin Yong Yun Goes to Church” by S. J. Rozan. The presence of an Asian protagonist/sleuth is certainly better than the evil stereotypes of Sax Rohmer and Edgar Wallace, but is the mere presence of this character breaking Knox’s Commandment? Rozan is another prolific author who has dipped into a beloved series. She has been writing books about the crime-solving team of New Yorkers Lydia Chin and Bill Smith since 1994. Chin Yong is Lydia’s mother and has previously appeared in her own short cases. In this one, she investigates shady happenings at the local Catholic church where a new priest, one Father Knox (!), seems to be running a scam. No language barrier will keep Chin Yong Yun from sorting the problem out, and she makes for as charming and funny a narrator as she is a wise amateur sleuth.

My two favorite stories both channel The Great Detective. Daniel Stashower’s stunning tale, “The Forlorn Penguin,” begins: “I saw a little of my friend Sherlock Holmes during the chill winter of ‘97.” From there, it takes off into areas I dare not spoil here. I suppose it breaks a rule not found in Knox (who is referenced here), something to do with presenting a problem without a solution. But sometimes you have to put genre aside and just let a story get to you the way this one does me. Stashower’s previous writings include Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle, and his love of Sherlockiana is laid out in abundance here in ways that will surprise you.

“The Island Boy Detective Agency” is a delight from start to finish, thanks to its nine-year-old narrator and budding sleuth, James Jackson Judd. Jackson lives in a Bahamian paradise, much like his creator, Marcia Talley: a long narrow spit of sand where his mother manages the hotel restaurant and where Jackson spends much of his time reading the books left behind by sailors and other guests. Everything he reads provides knowledge to the boy, none more so than his favorite book, The Complete Sherlock Holmes. As a result, whenever crime strikes, Jackson manages to steer the local Constable to the culprit. And when danger from the outside world threatens the sanctity of his island home . . . I dare you to read this story and not be impressed!

In contrast, the final story, “Ordeals” by co-editor Art Taylor, is a little clunky. A three-character drama set in some olden time (the dialogue feels as if it has been translated from a dead language), I can hazard a guess as to which Commandment it’s breaking, but it’s also an advertisement for that oft-heard advice: “Never underestimate the help!”

We get a lovely sorbet at the end of our Knoxian meal from none other than Peter Lovesey, the focus of one or two C&L collections himself. “Knox Vomica” is a poem in the vein of Ogden Nash which gathers all the great detectives of yore together to witness the savaging of every Commandment during a series of murders. That the deaths take place at Cliché Manor will give every veteran mystery reader a leg up as to whodunnit! It’s a fitting end to a charming collection.

Happy 30th, Crippen & Landru! Long may you continue to publish!

Wonderful! Thank you! I have the book on order!

LikeLike

Thank you for the review! Let us know if you want to review future works.

LikeLike

Pingback: Who Was That Lady? Craig Rice: The Queen of Screwball Mystery (2001; 2021) by Jeffrey Marks – crossexaminingcrime