“I’ll never forget the way he kissed me just before he beat it with all of my money.”

On a fateful day in 1930, a young woman walked into the San Francisco offices of private detectives Sam Spade and Miles Archer. Miss Wonderley asked them to find her missing sister, who had gotten herself involved with a cad named Floyd Thursby. Spade and Archer liked the money she offered; they also liked her legs, and so they took the case. By the next morning Miles Archer would be dead, and Sam would come to realize what he had already suspected: everything about “Miss Wonderley” – her sister, her story, even her name – was a lie.

It’s pretty much a rule of the genre that when a pretty dame walks into a P.I. or a lawyer’s office in search of help for her “sister” or her “cousin” or says she’s “asking for a friend” that the girl is, to put it mildly, stretching the truth. And so, when Helen Crocker comes to Perry Mason’s Los Angeles office one morning in 1934 and asks “on behalf of a friend” whether the woman’s husband would be considered legally dead if he went down in an airplane crash seven years earlier, Perry is disinclined to believe her. And as her questions grow curiouser and curiouser – can the woman collect the man’s insurance if there is no body? ss her new marriage invalid if he turns up alive? can she be held liable for the murder of a “legally” dead man? – Perry’s back is up!

In such a situation, Sam Spade played it cool – and lost his partner. But in The Case of the Curious Bride (1934), Mason’s fifth recorded case, the ace attorney pushes back hard against Miss Crocker. He insists that her “friend” must come to him “herself” for the answers. He even alludes to the idea that perhaps Miss Crocker herself is the new bride in this perilous situation; hadn’t his secretary, the cool, competent and delightful Della Street, already deduced that the client was only recently married by the way she tenderly stroked her own wedding ring?

Unfortunately, Perry’s tactics misfire: rather than own up to the truth, the girl flees the office. She is fortunately spotted on her way out by legal wingman Paul Drake, Mason’s own Sam Spade, who notes the direction in which the client is fleeing and the interesting fact that she is being tailed. And because this is early Erle Stanley Gardner, not only is the plot about to get a whole lot more byzantine and noirish, but the author is going to let us in on Mason’s thought processes, both as a lawyer and a detective, starting with his immediate understanding that he has done wrong by a client:

“What right have I got to sit back with that ‘holier than thou’ attitude and expect them to come clean with a total stranger? They come here when they’re in trouble. They’re worried and frightened. They come to me for consultations. I’m a total stranger to them. They need help. Poor fools, you can’t blame them for resorting to subterfuges. I could have been sympathetic and drawn her out, won her confidence, found out her secret and lightened the load of her troubles. But I got impatient with her. I tried to force the issue, and now she’s gone.”

It is to Perry Mason’s credit that he refuses to give up on the girl that got away. As he points out, the fact that Della had collected a retainer made him legally responsible to help her, but still, in the early part of the novel, Perry goes to frantic lengths to track down Miss Crocker – whose real name, by the way, turns out to be Rhoda Montaine and who, you can be sure, was not asking questions about marriage, dead men, and murder “on behalf of a friend.” Frankly, this latest client is a real piece of work, but then desperation can render a person equal parts cunning and clueless. Soon enough, Perry meets the “dead” first husband, who is a total monster, and the second husband, who is no prize either. There really are no admirable characters here, although Rhoda’s chief crimes are impetuousness and naivete. How else to explain her belief that she could pull a fast one on Perry Mason?

Yes, a murder occurs, and, yes, Rhoda is arrested for it, and even in jail she manages to confound her lawyer’s wishes and nearly land herself in the electric chair. Ultimately, Curious Bride gives us only the bare bones of a whodunnit; mostly, it is an object lesson in The Flim Flammery of Perry Mason, how he manipulates the law and the press (in a wonderful scene where Mason confronts Rhoda in an airport phone booth) to get his client an acquittal. At one point, we get the rare pleasure of watching Mason superbly handle a divorce case. But the real example of his artistry has to do with a very long con he pulls over some eventual evidence in Rhoda’s murder trial that deals with the various bells that ring in our homes.

Other than that, it’s business as usual. Della is bright and starry-eyed throughout, and Paul Drake is dogmatic and helpful. We also get the typical ADA in the person of John C. Lucas. Determined to bring Mason down where others have failed, Lucas starts out pompous and over-confident and winds up an apoplectic mess. In a way, you can almost feel sorry for him, not only because he’s clearly no match for this defense attorney but because Mason’s gimmicks this time around seem particularly sleazy. Sleazy enough for even Della to question her boss:

“’Chief,’ she said, ‘was that doorbell business on the square?’ He smiled down into her troubled eyes. ‘Why?’ he asked. ‘I’ve always been afraid,’ she said, ‘that someday you’d go too far and someone might make trouble for you. You see . . . ‘ His laugh interrupted her. ‘My methods,’ he said, ‘are unconventional. So far they’ve never been criminal. Perhaps they’re tricky, but they’re the legitimate tricks that a lawyer is entitled to use. And cross examining a witness. I have got a right to use any sort of test I can think of, any sort of a buildup that’s within the law.”

Having witnessed the machinations of several teams of modern-day lawyers to stall the multiple legal trials of one ex-president these days, I’m more willing to believe Mason’s self-defense. One of the many delightful aspects of reading the earlier novels is the amount of insight Gardner gives us along into Perry’s methodology and philosophy. In later books, the author tended to insert a dry preface about a point of law, although this didn’t necessarily have anything to do with the case before us. Here, at least, Gardner offers some explication for his hero’s zany tactics:

“Perry Mason specialized in trial law, mostly criminal law. His creed was results. Clients came to him because they had to. There was no repeat business. Ordinarily, a man is arrested for murder but once in a lifetime. Mason realized that his business must come from new clients, rather than from those who had previously been acquitted. As a result, he ran his office without regard for appearances or conventions. He did what he pleased when it suited him to do it. He had sufficient ability to score in the conventions.”

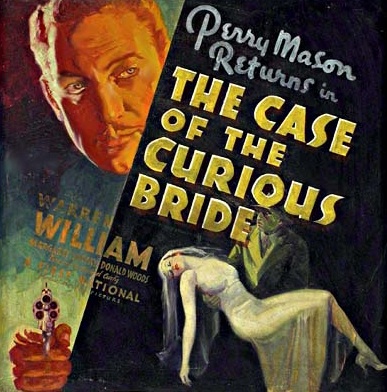

As I said, in the end The Case of the Curious Bride barely cuts it as a whodunnit. With only five major characters, including the victim and the defendant, there aren’t many options for where the case can end up. (A better title might have been The Wising-Up of Rhoda Montaine.) Still, there are actually two adaptations to this novel, a 1935 film starring Warren William as Mason, Margaret Lindsay as Rhoda, Claire Dodd as Della Street, and featuring a young actor named Errol Flynn as the late, unlamented Gregory Moxley, and, of course, an episode of the 1950’s TV show, Perry Mason(Episode #5 of Season Two, to be exact.) Both take advantage of the relative simplicity of this plot to be pretty darn faithful to the original. The film suffers a bit from that ol’ Warner Brothers humor, largely due to Allan Jenkins as Paul Drake-stand-in Spudsy. The TV episode lifts dialogue wholesale out of the book; too bad it couldn’t lift a little of the dramatic zip, and Raymond Burr makes a pretty stodgy Perry compared to the guy on the page.

In the end, Curious Bride makes a fair-to-middling start in our Gardner-esque journey through the world of matrimony. Next month we switch genders for a 1941 nightmare in Hollywoodland!

I do like the Warren William version, though Warners did lighten the tone greatly as part of a deliberate attempt to model it after the success of The Thin Man. It moves at a great cllip and Michael Curtiz as always does a great job directing it, a fun double bill with his version of The Kennel Murder Case.

LikeLike

I agree with Sergio – I have not seen the 1935 film in a long time, but I remember it being entertaining and done with the usual Michael Curtiz aplomb. The novelty of seeing pre-stardom Errol Flynn made it a curiosity too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: THE ERLE STANLEY GARDNER INDEX | Ah Sweet Mystery!