I talk to my mother every night on the phone, and invariably, we get around to the news of the day. It wears my mother down, and she moans, “What a world, what a world we live in today!” That’s when I have to remind her, ever so gently, that the world isn’t so very different from when she was a girl. For proof, all I have to do is take her back to Hollywood in the ‘40’s.

That’s what I recently did myself: this winter, Stanford University offered a class on the Hollywood Blacklist, taught by my friend Elliot Lavine. Over the course of six weeks, we watched around thirty films, mostly crime dramas, films noirsand Westerns, that illustrated the shameful history of Hollywood’s capitulation to the demands of HUAC (the House Un-American Affairs Committee). Our focus was narrow, so I’m not going to give you a lecture on the general history of the committee or of the times. But here’s a smidge:

Suffice it to say that we had formed an uneasy alliance with the U.S.S.R. during the war, and that this merger swiftly fell apart in the wake of the war’s end. Was Communism a threat in America? There were certainly instances of espionage, ranging from the Soviet capture of plans from the Manhattan Project in the early 40’s to the Ethel and Julius Rosenberg’s treason in 1951. The blacklist, however, concerned something far more insidious. It was a way of targeting progressive intellectuals, Jews, Black people, union organizers and others who had been drawn, however briefly, toward the precepts of the American Communist Party in the wake of the Depression. HUAC used Communism to draw a line in the sand between those who were loyal to America and those who were not. To prove one’s loyalty, a person had to renounce Communism – even if they hadn’t embraced its views or thought about it for years. Then they had to help the committee supplying the names of anyone they knew who had also been associated with the Party, however briefly or fleetingly. Failure to do so would result in the loss of one’s job, even one’s freedom, and destroy one’s standing in society.

HUAC believed that Hollywood, run by Jews and proud of its legacy of shining a light on society’s ills, had long been a hotbed of Communists, liberals and rabble rousers. In truth, the industry had certainly gathered among its writers, directors, and actors many people who had dabbled in a wide range of ideologies, including Communism. Some were still avowed Communists, but most had merely sampled the Party and then left it behind a long time ago.

That didn’t matter: writers, directors and actors were called before HUAC and, in a series of public hearings, were asked about membership and associations. If you watch any of these hearings (many are on YouTube), it may or may not surprise you to watch famous people from stars to studio heads fall all over themselves declaring their loyalty to America and showing their willingness to throw their friends and fellow workers to the wolves. Some tried to capitulate as quietly as they could so that they could get back to work; others, like Ginger Rogers and Ronald Reagan, became spokespeople for the Cause.

And then there were the ones who refused to cooperate. The most famous of these perhaps came to be known as The Hollywood Ten, a group of producers, directors and screenwriters who, in 1947, appeared before HUAC, refused to name names, and paid for their uncooperativeness with imprisonment and banishment from the film industry. Several of these men – producer Adrian Scott, director Edmund Dmytryk, and writer Dalton Trumbo – became part of the focus of our class. Joining them were later victims, like directors Abe Polonsky, Jules Dassin and Joseph Losey and a wealth of actors, including John Garfield, Howard da Silva, and men like Art Smith whom you’ve probably never heard of because they were blacklisted, One of the overriding messages we took with us from this class was the acknowledgement of all the potential great art lost because of what happened to these artists.

Here are some of the highlights of the course:

We had a fascinating match-up of films for our third class: Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954) and Thieves’ Highway, a 1949 film noir directed by Jules Dassin. Elia Kazan is notorious for his full cooperation with HUAC. There is no denying his artistic genius or the price he paid for naming his peers to the Committee. Kazan came to resent that cost, and the result is On the Waterfront. The film is powerful, a bit dated, and justifiably famous, but Dassin’s film, dealing with similar themes, is leaner and tougher. It concerns a trucker (Richard Conte) trying to get back at the San Francisco fruit seller who destroyed his father’s career.

The villain in both films is played by Lee J. Cobb, but in Dassin’s film he’s more petty, more charming, and more subtle. And while Waterfront’s Eva Marie Saint is a sweet faded prize for Marlon Brando’s Terry Malloy if only he can do the right thing (which, for Kazan, meant naming names), she’s no match for the sultry Valentina Cortese (Dassin’s girlfriend at the time) as Rica, the “heart of gold” prostitute in Thieves’ Highway, who flips the usual noir narrative between the sexy bombshell and the “good” girl, here played by Barbara Lawrence, who turns out to be an opportunistic priss.

The hardest thing to take during the six weeks was seeing how much these historical films paralleled current events. The ability of men in power to stir decent folks into a mob or to convince us to abnegate our own rights and freedoms has been going on for a very long time (sorry, Mom!) Politicians have always represented opposing factions, but they had occasionally managed to strike compromises and get the job done. Now, in the name of their beliefs, they refuse to work. And they have encouraged the citizenry to reject opposing points of view, even to the point of violence. This abuse of power and/or responsibility made for some of the most powerful viewing in our class. We watched so many hard-hitting scenes of mob violence that we couldn’t not think of the January 6 insurrection and other recent examples.

Some of my favorite films:

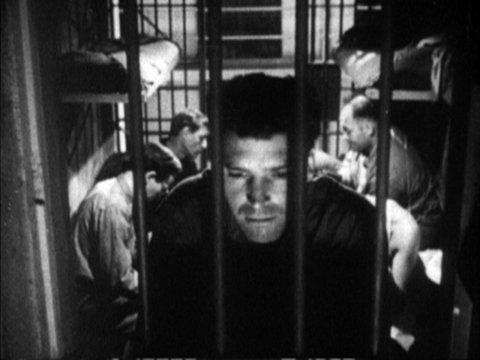

Brute Force (1947)

Directed by Jules Dassin, this indictment of the prison system concerns a group of inmates, led by Burt Lancaster, who fight back against the prison guard (Hume Cronyn) who seems to have modeled his fascistic rule after Adolf Hitler. He physically tortures prisoners and “turns” them with promises of gentler treatment if they “name names.” It leads Lancaster to plot a group escape which, this being a film noir, ends badly for all. The final riot is breathtaking to behold. Like director Dassin, actors Jeff Corey and Art Smith were blacklisted.

Force of Evil (1948)

We spent a week covering the tragic career of John Garfield, an actor I believe was every bit as good as Cagney and Bogart, and whose work presaged the “New Age” of actors like James Dean and Montgomery Clift. Garfield had heart problems, but it is widely believed that the stresses placed on him by HUAC led to his early death at 39 from a heart attack. We watched Force of Evil in a pairing with the more famous Body and Soul. These are the two films Garfield made with his own company before he and the film’s director, Abraham Polonsky, were blacklisted. One of the great crimes is that Polonsky, a gifted artist who was a screenwriter for Body and Soul, was unable to work for years.

I like the boxing picture all right, but Force deserves to be a classic in its own right. Garfield is the bad guy here, a young lawyer for the Mob who conceives of a plan to control the numbers racket by forcing out all the small betting concerns who sell lottery tickets to the working class. One of these concerns is run by Garfield’s older brother (Thomas Gomez), who had sacrificed his own dreams to put his kid brother through law school and into a better way of life.

Of course, the film focuses on the conflict between siblings, but it also explores the problems of various secondary characters to tell its tragic story. The final scene is devastating, although it does offer a measure of hope.

High Noon (1952)/Terror in a Texas Town (1958)/Silver Lode (1954)

We spent one session discussing three Westerns, all with ties to the Blacklist. Although they couldn’t have been more different in style, all tackled the theme of the individual’s responsibility to his neighbors. High Noon was the glossiest of the three, and some scholars call it an allegory for McCarthyism because its screenwriter, Carl Foreman, was summoned during the film’s production to testify before HUAC He readily admitted that he had joined the Communist Party in 1938 and had remained a member for four years before becoming disillusioned. Because he would not reveal the names of fellow members, Foreman was blacklisted and barred from writing in Hollywood. He managed to earn his living writing screenplays for which other writers got the credit by acting as fronts. This extended to 1957’s Bridge on the River Kwai, which earned a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar – for Pierre Boulle, the novel’s author, who spoke no English and had had nothing to do with the film. Foreman would eventually receive the credit for Bridge and make several other successful films, including The Mouse That Roared and Born Free.

In High Noon, Marshall Will Kane (played by Gary Cooper, after John Wayne turned the role down because he felt the script was “un-American”) must postpone his honeymoon to face down the outlaw he put in prison. Because of her religious principles as a Quaker, the Sheriff’s bride (Grace Kelly) refuses to condone her husband taking up a gun to defend himself. This is somewhat understandable, but the actions of the rest of the townsfolk of Hadleyville are inexcusable: despite their ready acknowledgement that the Marshal singlehandedly made their town safe to live in, not one person will stand beside him to face down the outlaw and his gang. Their reasons range from cowardice to jealousy, and the end result is that Marshall Kane stands alone at the end. Well, not quite alone – at the last minute, his wife renounces her principles, picks up a gun, and saves her husband’s life!

I have to admit that watching Cooper in those final scenes, looking too old to play the part, made me think of President Biden’s current situation with the voting public, who deem him too old to run, despite that fact that he is certainly not standing alone as our country’s leader. Will Kane and the missus manage to defeat the outlaw and his gang – at which point the townsfolk slink out of their hiding places to offer their congratulations. It’s too little, too late, and the Kanes depart Hadleyville forever.

The Swedish immigrant in Terror in a Texas Town (Sterling Hayden) and the young capitalist in Silver Lode (John Payne) also have to face down a criminal element with no help from the population. Silver Lode is practically a remake of High Noon, with the big difference that the town doesn’t so much cower in fear as slowly turn against the hero. Their willingness to believe the worst in him allows them to excuse or ignore the worst in themselves. Texas Town was written by Dalton Trumbo and, deals with, among other things, the immigrant experience. Considering how, at the time, all these characters were immigrants of the children of the same, it’s a powerful indictment of those with power wielding it to subjugate others. It’s tragic how easily the folks in all these films forsake their own power by abnegating their responsibility to preserve it.

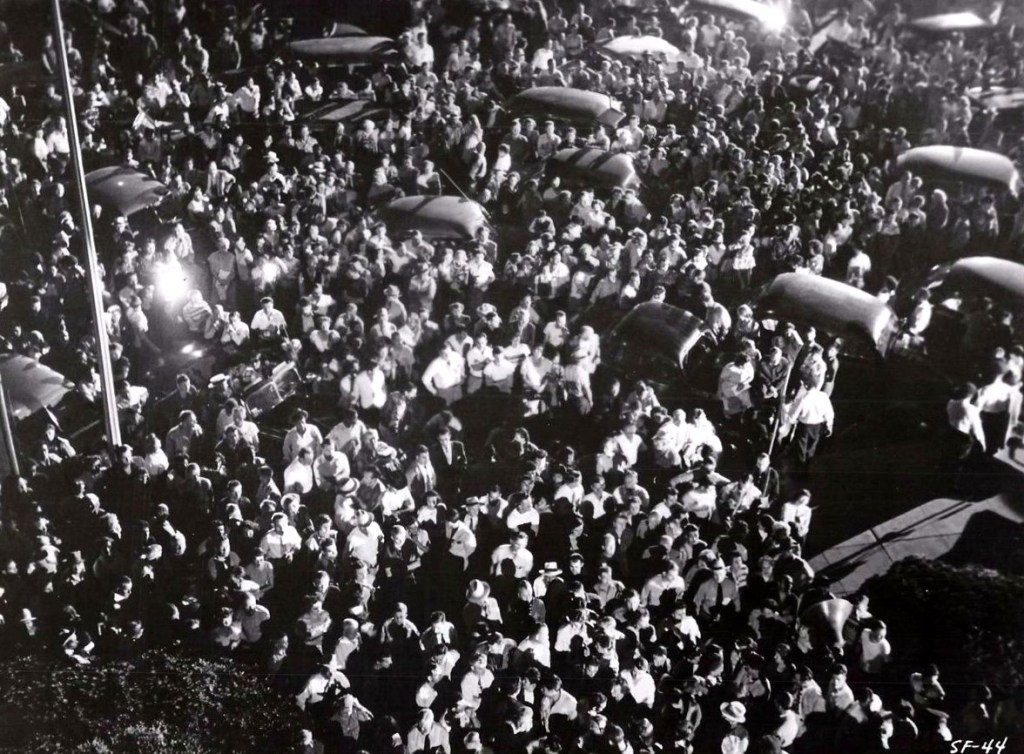

The Lawless (1950), The Sound of Fury (aka, Try and Get Me, 1950) and M (1951)

Our final round of films, depicting issues of anti-immigrant bias and mob violence, induced squirms in the class for their connotations to modern events. Cyril Endfield directed The Sound of Fury, and Joseph Losey directed the other two films. Both were blacklisted, and Losey would spend the rest of his life directing films in Europe. Endfield went to England as well, but years later he would actually name names and resume directing in the States, much to the chagrin of his fellow exiles.

Both The Lawless and The Sound of Fury have ties to Fritz Lang’s 1936 classic of mob violence, Fury. Losey studied Lang’s film while preparing for The Lawless, a wrenching study of a town where the white population is all too eager to blame all of its ills on the Mexican community that lives on the other side of the tracks. MacDonald Carey plays one of the most wishy-washy of heroes, a journalist who pretty much has to be shamed into taking action on the right side. His stance prompts a horrific riot where the populace, angry at being lectured to by the press, destroys Carey’s office and tries to lynch an innocent immigrant boy who has been railroaded on a variety of charges. The ending is open-ended, but at least it affords us a measure of hope – as long as we find the courage to stand up for our principles.

The Sound of Fury is actually based on the same murder case as Fury, the murder of Brooke Hart that took place right down the road from me in San Jose, California in 1933. Two men were arrested and charged with Hart’s murder, and the press coverage so inflamed the town that both men were lynched by a mob. While Spencer Tracy was innocent of any crime in Fury, the guilt of both men in the later film is unassailable. One of these men, played by Lloyd Bridges, is a narcissistic psychopath, while the other (Frank Lovejoy), is a down-on-his-luck family man who seems fated to make one bad choice after another. After watching the final thirty minutes of this film, you can’t help feeling sorry for both these men. And the scenes of the mob assaulting the jail, attacking policemen, and smashing property, are eerily reminiscent of the scenes we all witnessed on January 6, 2021.

The same goes for M, Losey’s remake of the 1931 Fritz Lang film of the same name. I have to say I think the remake is even better, and it leads us to the same weird feelings of pity for the child murderer at its center (a remarkable David Wayne) who is nearly destroyed by a kangaroo court made up of criminals and street people. In the climax, a drunken mob lawyer (stage actor Luther Adler, also blacklisted), tasked with “defending” the killer, decides to take his job seriously and implore the crowd to let the man have the access to real justice that is the right of all people. His words infuriate the mob boss (Martin Gabel) who insists the lawyer stop lawyering and “make the crowd laugh.” In the end, the killer is quietly escorted away by the police, and it is the lawyer who is shot to death, ensuring that the mob boss who killed him will face real justice for taking the law into his own hands.

Both M and The Sound of Fury inspired discussion of our legal system, justly elevated above the Biblical “eye for an eye” morality and now sadly besieged from without and within. Yes, our system grinds slow, and we have seen instances where it is manipulated. But we have films like these, created by men who were tossed out of society by a rigged system for having ever examined points of view that contrasted with what HUAC deemed acceptable. These are films that remind us of how things are supposed to be, how easy it is to regress to brutality, and the consequences of that regression. Many of these films stayed under the radar for years, paying a price for the ideas they presented at the time. Seeing how closely these works of art from seventy years ago parallel our current behavior makes viewing and studying them more relevant than ever.

Sounds like a great class but such a dreadful period (I’m with your Ma in this, it seems even worse now – it’s this sense of rowing backwards that is so upsetting). Hellman’s terming of the McCarthy period as “scoundrel time” always seemed the most appropriate to me. Are you sure Foreman actually worked on MOUSE THAT ROARED? I know his company made it but not sure what he actually did on it. THE GUNS OF NAVARONE is a better-known example of his later work on which his name actually appears as a writer and producer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you’re right: on Wikipedia, he’s listed, as only the “presenter!” From now on, when I write about movies, you’re going to have to be my editor!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry, too busy learning from you and enjoying what you write.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: GOURMET VS. G-MEN: The Doorbell Rang | Ah Sweet Mystery!