“Crime? Can’t we talk about anything else? Don’t we get enough of it in books and films? I’m sick to death of this crime, crime, crime, wherever you turn.”

If this sounds like an odd complaint coming from a member of a Classic Crime Book Club– well, you’re right. While we have tended to have more strike-outs than home runs in our title selection, it’s not for lack of trying. Despite our incredibly varied tastes, the one fact upon which we’re all agreed is our (here comes the pun!) undying love for murder mysteries.

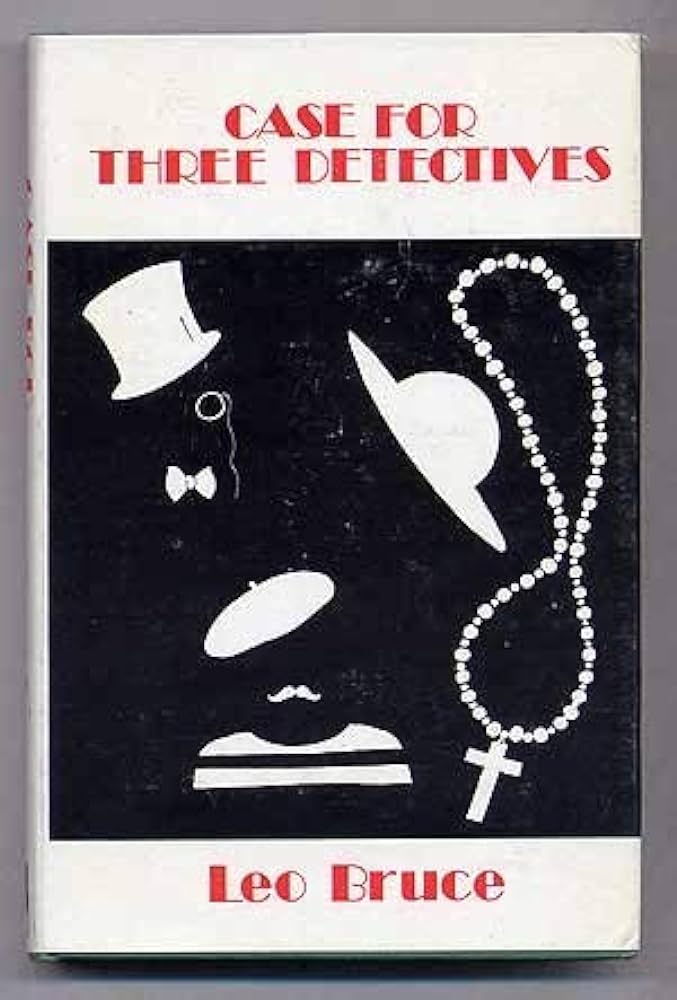

No complaints from me his month, for we picked a beaut called Case for Three Detectives. It’s my first time reading a novel by Rupert Croft-Cooke, a well-born, well-educated, well-traveled and highly prolific author whose homosexuality would send him to prison and then into exile (although he did manage to make it back to jolly old England in time to live to a ripe old age. In case you’ve never heard of Rupert, it might be because when he started writing mysteries in 1936, he assumed the pen name of Leo Bruce. Under that pseudonym, he wrote eight mysteries featuring homely Police Sergeant Beef and then switched sleuths and produced two dozen novels about schoolmaster Carolus Deene. From all I’ve heard, Bruce’s first was his best, and whenever people read a Carolus Deene mystery, they end ujp muttering, “Where’s the Beef?”

In many ways, Case is an extraordinary debut. It certainly works as a traditional puzzle mystery; in fact, it’s even an example of a locked room murder (with an entry in Robert Adey’s invaluable reference work to prove it!) If conventional hindsight suggests that here we are only a few years until the slooooooww demise of the Golden Age commenced, Bruce’s book works as both an homage to some of its greatest writers and a parody of their work and the work of the dozens of classic crime authors whose titles covered the bookshop shelves that year.

(Just for example, 1936 saw new works from the likes of Margery Allingham, E. C. Bentley, John Bude, Christopher Bush, John Dickson Carr, Agatha Christie, Clyde B. Clason, Freeman Wills Crofts, Todd Downing, Brian Flynn, Erle Stanley Gardner, E.C.R. Lorac, Ngaio Marsh, E.R. Punshon, Ellery Queen, Patrick Quentin, Helen Reilly, John Rhode, Rex Stout, Josephine Tey, S.S. Van Dine, and Henry Wade. About half these people published more than one title that year; as might be expected, John Rhode published five.)

From the start, Case for Three Detectives announces itself as a stunning work of meta-fiction, the best to my knowledge since Anthony Berkeley’s The Poisoned Chocolates Case from 1929. The main point of Berkeley’s novel was to show that a basic crime scenario could be twisted in innumerable ways to allow for any solution its creator wished. But the novel also played with the idea of the Great Detective: Roger Sheringham, the ostensible hero-sleuth of Berkeley’s novels, offers the most insanely clever solution – and then is utterly crushed by the mousy Mr. Chitterwick, who not only imparts the correct solution but also provides the perfect meta-fictional commentary:

“I have often noticed… that in books of that kind it is frequently assumed that any given fact can admit of only one single deduction, and that invariably the right one. Nobody else is capable of drawing any deductions at all but the author’s favourite detective, and the ones he draws (in the books where the detective is capable of drawing deductions at all which, alas, are only too few) are invariably right.”

Bruce’s debut novel is moving in a similar direction, but he goes one better on Berkeley by providing not one, not two but three brilliant sleuths to tackle the problem of who murdered the affable hostess Mary Thurston in her locked bedroom. As for the meta-commentary, it comes flying at us from the start, in conversation among the guests at the Thurston’s weekend party and in great part from our narrator-slash-Dumb Watson, Mr. Townsend. We come upon the house party one evening arguing the merits and detriments of detective fiction.

The party makes the distinction between real life murders, which tend to be “a sordid business about a strangled servant-girl” and the more glamorous, exciting world of fiction:

“You, all of you, know these literary murders. Suddenly, in the middle of a party – like this one, perhaps – someone is found dead in the adjoining room. By the trickery of the novelist all the guests and half the staff are suspect. Then down comes the wonderful detective, who neatly proves that it was, in fact, the only person who you never suspected at all. Curtain.”

The chief detractor is one of the guests, a writer named Alec Norris, who might remind you of an even more charmless Raymond West. He bemoans the fact that his novels of psychological despair don’t hold a candle in popularity to crime fiction.

“Literary crime is all baffling mystery and startling clues . . . It has become a mere game like chess, this rating of murder mysteries. While in real life, it is no game, but something quite simple and savage, with about as much mystery wrapped around it as that piano leg. And that’s why I’ve no use for detective fiction. It’s false. It depicts the impossible.”

When actual murder rears its ugly head a mere few hours later, Bruce amusingly chronicles how the brutal crime quickly veers into classic crime territory. Townsend is having a brandy before bed with his host and the family solicitor when they hear several piercing screams. They rush upstairs to Mrs. Thurston’s room and have to break down the door, only to discover her in bed, her slashed throat covered in blood.

The local policeman, Sergeant Beef, is summoned from the pub where he just won a darts tournament. But, unaccountably, three world-famous sleuths also show up to investigate. Each is a slightly comical but spot-on parody of a famous sleuth. First, we have Lord Simon Plimsoll, who not only emulates the qualities of Peter Wimsey, right down to the accompaniment of his manservant Butterfield (who seems to do all the legwork), but he also illustrates the distinct shift in tone that tends to accompany an eccentric sleuth into a murder investigation, as Townsend relates:

“I liked him, because from the moment he arrived at that house the somewhat macabre atmosphere of the previous evening was dissipated. His cheerful and inquisitive nature seemed to discourage any morbid dwelling on the horror of Mary Thurston‘s death, and to induce everyone, whether bereaved or guilty, into a pleasant and eager state of curiosity.”

The game is afoot for more than one sleuth. Also on the scene is M. Amer Picon, the spitting image of a certain Belgian detective:

“I became aware of a very curious little man who was on all fours beside the flower bed in which I had discovered the knife during the previous evening. His physique was frail, and yooped by a large egg-shaped head, a head so much and so often egg-shaped that I was surprised to find a nose and mouth in it at all, and half expected its white surface to break and release a chick.”

The little man calls himself “Papa” Picon, and he peppers his dialogue with constant French-isms; my favorite is how he calls the local cop “Sergeant Boeuf!” Finally, we have Monsignor Smith, a brilliant homage to Father Brown. (One of the most startling coincidences associated with this novel is that it was published in the year of G.K. Chesterton’s death.) Townsend describes him as “a human pudding,” and aside from napping and tearing bits of bread with his fingers, he is given to weird homilies and symbolic speech. When someone suggests the the murderer flew out of the victim’s window as if he had wings, Smith pontificates:

“There are the wings of aeroplanes and of birds. There are angels’ wings, and . . . there are devils’ wings . . . but there is flight without wings, more terrible than flight with wings. The Zeppelins had no wings to lift them. A bullet has no wings. A skillfully thrown knife, flashing through the air like a drunken comet, is wingless, too.”

For a great swath of the novel, the three detectives sit in consultation with Townsend and Sam Williams, the attorney, trying to determine which of the guests or servants murdered Mary and how they went about it. Townsend also gets his chance to “work” with each sleuth separately, which he quickly comes to realize means asking questions and acting awestruck. In short, he behaves as he has seen countless Watsons and witnesses behave in the detective novels he loves. In a more serious vein, Townsend comes to see the dark side of treating murder as a game. Having forgotten “more than a perfunctory duty of mourning,” Townsend begins to resent the cavalier lightness with which these three egotists treat the case:

“I felt nauseated, suddenly, with the whole affair. This relentless tracking down of the criminal seemed gruesome. Lord Simon, gently sipping his brandy, so obviously considered it all to be a most absorbing game of chess, ‘something to occupy a chap,’ that for a moment I lost all patience with him. And the brilliant little Picon, whose humanity was more evident, he too, could not help enjoying his own efforts – and that disturbed me. Certainly, I had never known Monsignor Smith actually hand a man over to the Law, but even that was partly because the criminals he discovered had a way of committing suicide before he revealed their identity.”

As for poor Sergeant Beef, he isn’t in the house an hour when he frankly announces that he knows who the culprit is. But the power of Knox’ Commandments is too great: Beef is dismissed as a boob, and the Three Detectives do their business until each one formulates a solution that is emblematic of the kind to which Wimsey, Poirot and Father Brown tend to arrive. Each solution is certainly worthy of the mind that conceived it – but, as you may expect, in this novel it’s slow and steady that wins the race, as Sergeant Beef knocks three fairy tale endings out for the count and comes up with the truth. As he explains,

“I’ve told you I ‘aven’t got no theories. I’m no good at anythink like that. I’m just an ordinary policeman, as you might say . . . I ‘ave to use these regulation methods. Never do for me to get up to any fanciful tricks . . . “

This is disingenuous of the good Sergeant, or perhaps of the author speaking through him, for the solution he propounds is no less imaginative or twisty as the theories proposed by the others and the most satisfying of them all. I thought I had it figured out, and I did manage to get some of it. But there is that twist at the end, and it’s a good one. I especially like how Bruce takes some of these meta elements and turns them into actual clues. My only problem is that I would argue that Beef’s actions at the climax result in an unnecessary and tragic death, one that – surprise! – nobody seems to take very seriously.

Never mind: with its combination of the traditional and the meta-fictional, Case for Three Detectives is a fresh, lively celebration of – and commentary on – the Golden Age of Detection. Sergeant Beef is that rare thing: a well-done country policeman! And if Wilson and Chandler want to grumble about the Beef – let ‘em eat cake!

“Just for example, 1936 saw new works from the likes of Margery Allingham, E. C. Bentley, John Bude, Christopher Bush, John Dickson Carr, Agatha Christie, Clyde B. Clason, Freeman Wills Crofts, Todd Downing, Brian Flynn, Erle Stanley Gardner, E.C.R. Lorac, Ngaio Marsh, E.R. Punshon, Ellery Queen, Patrick Quentin, Helen Reilly, John Rhode, Rex Stout, Josephine Tey, S.S. Van Dine, and Henry Wade. About half these people published more than one title that year; as might be expected, John Rhode published five.”

This is one of the most fascinating things about the Golden Age to me! So much so that I have started a spreadsheet for my own edification.

Case for Three Detectives has long been on my to-read list and I have never gotten hold of a copy. I will need to rectify that. Your praise for it only adds to the many accolades I have come across over the years.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Plus . . . it’s funny (wink, wink!)

LikeLike

About time you read this terrific book – but dude, you really have to stop nicking my titles for our forthcoming battle of the books!

LikeLike

Case for Three Detectives is Bruce’s best book; it’s a brilliant parody. The rest of Bruce, by and large, is negligible; he’s an atrocious plagiarist, and the Deene books are dull. That’s *my* “Beef”!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Otherwise, I remember reading one of Rupert Croft-Cooke’s novels – Exiles? – when I was in high school; between that and Evelyn Waugh, I got the impression that being gay meant emigrating to North Africa and being miserable.

LikeLike

Oh, and Gore Vidal, too. The City and the Pillar, much?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, yes, Vidal’s book gave me nightmares for, oh, forty years.

LikeLike

Pingback: “I’ve got a little list . . . ” Part II: Ten Favorite Mysteries of the 1930’s | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: MORE FUN AND GAMES WITH BOOK CLUB: Five Great Mystery Debuts | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: EVE OF POSSIBILITIES: Looking Back on ’24 and Forward to ’25 | Ah Sweet Mystery!