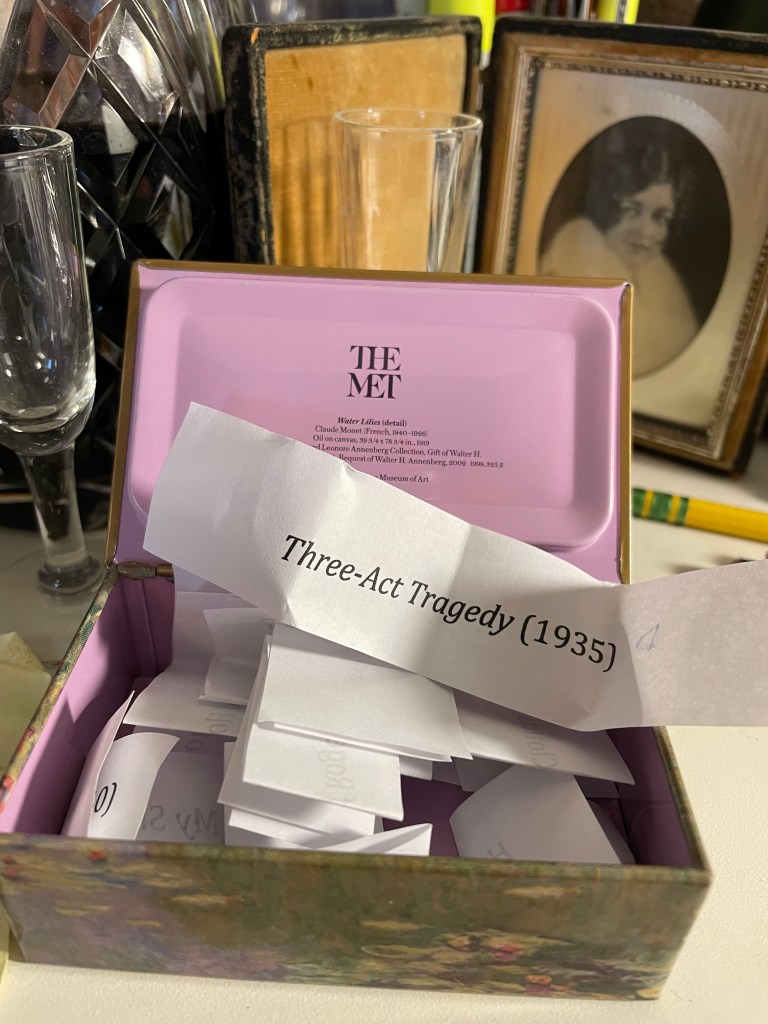

The order in which I read the sixty-six mystery novels of Agatha Christie was a total crapshoot, based largely on what cover or blurb struck my teenaged fancy. I couldn’t recite my reading chronology if I tried, although you always remember your first – and in my case, I remember my first four: And Then There Were None, Murder on the Orient Express, The Mousetrap and Other Stories, and A Caribbean Mystery. When it came to purchasing these books, I was on my own, at least until the 1970’s, when my Aunt Rosalie bought me the final six titles, one a year, as my own “Christies for Christmas.”

One year, I decided to splurge and buy two Christies at once, a Poirot and a Miss Marple; after all, two is better than one, right? I didn’t know any better, so I purchased two 1950’s titles: They Do It with Mirrors and Dead Man’s Folly. Maybe I thought from reading the blurb that Mirrors would combine classicism with modernity (“Two hundred-odd juvenile delinquents were no problem at all, compared with the half-dozen members of a wealthy family who were intimately connected with murder!”), but then I went and solved the mystery on page 57 – two pages before the murder occurred! Mirrors ended up 10th out of 12 in my rankings of the Miss Marple novels. The puzzle may be weak, and those extra murders feel extraneous, but I’ll tell you right now: at the time, I enjoyed it a lot more than Dead Man’s Folly.

And yet Folly contained a far more interesting blurb, at least on the back of my Pocketbooks edition: “’We are going to play Murder Hunt,’ explained Mrs. Oliver to Hercule Poirot . . .“’Each Player has a set of clues that lead to the body. The one who guesses the killer wins, and you, Monsieur Poirot, will present the prize.’”

The idea of a Murder Hunt tickled my fancy, especially one that ended, as this does, in a real murder!. And the return of Mrs. Oliver, my favorite character from Cards on the Table, was a welcome treat. But in the end, Dead Man’s Folly was an experience that this voracious young Christie fan had never expected: it was dull. Thus, when I pulled the slip last month indicating which book I would read for this month’s entry into The Poirot Project, I didn’t particularly jump for joy. However, I didn’t necessarily regret this third or fourth return to Nasse House, either, for the simple reason that – I have actually been there!!!

Nasse House, the mansion and grounds that make up the fictional setting for Folly, is based on Greenway, Agatha and Max’s summer home. When I read this passage – “Poirot was directed to a winding path that led along the wood with glimpses of the river below. The path descended gradually until it came out at last on an open space, round in shape, with a low battlement parapet. On the parapet, Mrs. Oliver was sitting.” – I knew exactly where Poirot was going because last September, fellow blogger John Harrison and I walked down that exact winding path to that same parapet, and I sat exactly where Mrs. Oliver had sat. We then wandered around the very same boathouse where Marlene Tucker had been killed and then hung out at the drawing room where the novel’s characters gathered for tea on the day before the fete. (Frankly, I would have put everyone in the library, a larger, nicer room.) I think we examined the bookshelves in what would have been Hercule Poirot’s guest bedroom – but I might have to go back and look around Greenway again to make sure. (Well, if you insist!)

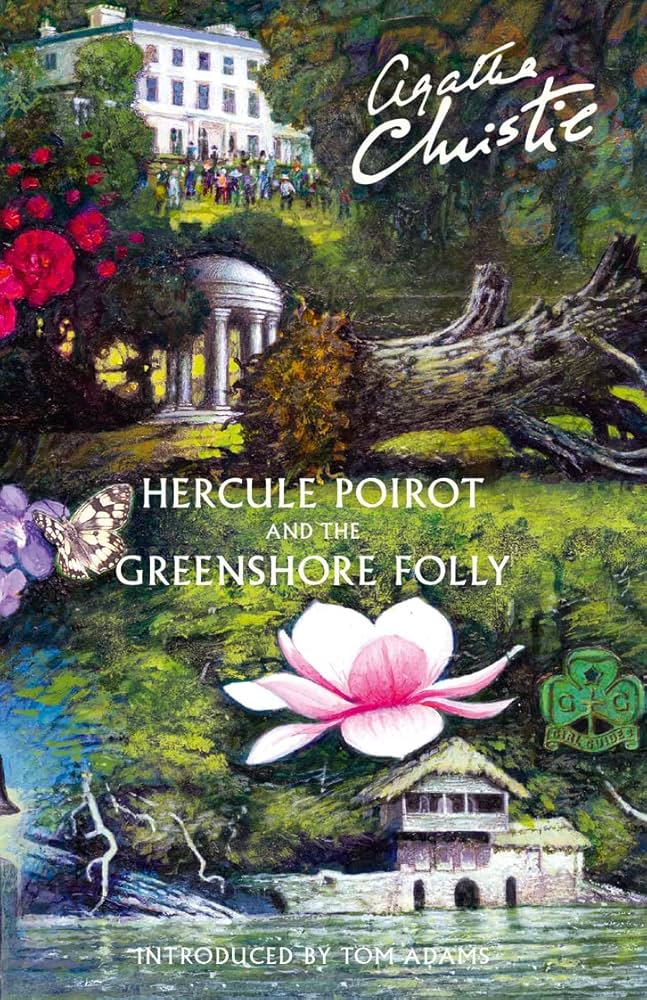

There is one more factor you should know about, since it had some influence on my opinions of the book this time. One of my first stops in London last September was to the flagship Waterstone’s in Piccadilly Circus. The mystery section was huge and the Christie sub-section impressive. Naturally, I had to buy something, and I selected Hercule Poirot and the Greenshore Folly, the one with the specially painted Tom Adams cover. For any of you not aware of this title, it’s part of the complicated history of Dead Man’s Folly, which began in 1954 when Christie approached her local place of worship (Churston Ferrers Church) to see if they would install stained glass windows. The author was prepared to write an original Poirot short story and assign the rights to the church to help pay for the windows.

The Diocesan Board accepted Christie’s generous offer – but as she wrote, the story grew in size until it became a novella, an awkward length for magazine publication. Christie also felt she had too good a story here: with some (as she calls it in her notes) “elaboration” of scenes, she thought she had the makings of a fine novel. Thus, she withdrew this particular story, wrote another one featuring Miss Marple, and not only got the job done at the Churston Ferrers Church but supplied her publishers with the 1956 “Christie for Christmas.”

I read The Greenshore Folly while in London, and when I started my re-read of Dead Man’s Folly, my strong inclination was that, in this case at least, shorter was better. (Which has nothing to do with the fact that, in my stockinged feet, I stand at a walloping 5’5″!) The following will explain whether or not I held to that attitude until the end.

* * * * *

The Hook

“I daresay I’m a fool, but I think there’s something wrong.”

Here’s the good news: Hercule Poirot’s old friend, the mystery novelist Ariadne Oliver, appears on Page One. I can understand Miss Lemon being upset about the lady interrupting Poirot’s dictation and demanding, without explanation, that he hop the next train to Nassecombe (a fictionalized Paignton) to assist her. Because while I, too, would drop anything to hang out for a while with Ariadne Oliver, the mission she has for Poirot is frustratingly vague.

Mrs. Oliver has been hired by the residents of Nasse House to develop a Murder Hunt for an upcoming fête, in place of the traditional treasure hunt that everyone has grown tired of. Everything is arranged for the next day’s festivities, but now, as the writer tells Poirot, “I daresay I’m a fool, but I think there’s something wrong.” The author believes that she has been subtly manipulated to alter her original murder plot in order to benefit some behind-the-scenes force, probably with malignant intent. “I can only say that if there was to be a real murder tomorrow instead of a fake one, I shouldn’t be surprised!” she tells Poirot.

This is fun, but if you understand both the character of Mrs. Oliver and the way the scenario plays itself out, it doesn’t hold together quite so well. First of all, there is her credo as a writer:

“. . . you see, this is my murder, so to speak. I’ve thought it out and planned it and it all fits in – dovetails. Well, if you know anything at all about writers, you’ll know that they can’t stand suggestions . . . That sort of silly suggestion has been made, and then I’ve flared up, and they’ve given in, but have just slipped in some quite minor trivial suggestion, and because I’ve made a stand over the other, I’ve excepted the triviality without noticing much.”

Mrs. Oliver can’t say for sure who is behind this jiggering of the plot (“It makes one feel such a fool not to be able to be definite.”), and one must accept that this vagueness is necessary to Christie’s puzzle – although Ariadne might have remembered one definite suggestion and the person who made it. Still, this isn’t the problem for me; Mrs. Oliver’s muddle-headedness has been well established. No, I have a couple of bigger issues to settle.

First, Mrs. Oliver insists that she has thought out and planned the entire basic plot. She even calls it “my murder.” But the gist of the murder game is that most of the characters Mrs. Oliver has created all have parallels to the characters in Folly’s actual plot: the country squire, the atom scientist, the disgruntled housekeeper, the European girl hiker. In fact, one of the characters, Esteban Loyola, the “uninvited guest,” is a direct copy of Etienne de Sousa, Hattie Stubb’s unwelcome cousin – a character who isn’t mentioned until long after the Murder Hunt has been developed. (I suppose one could argue that this is a Clew!!)

This parallelism suggests that Mrs. Oliver is far more susceptible to literary manipulation than she imagines. That’s all very well – until we learn which character she has selected to be the killer in her game. That choice conforms to a delightful running joke concerning Mrs. Oliver’s character: while she is often made fun of for her insistence on the power of feminine intuition, she just as often stumbles onto the truth before anyone else. This happens in Cards on the Table, and while she doesn’t name Mrs. McGinty’s killer correctly, she does offer up another suspect who turns out to be a second killer – someone who tried to do away with Hercule Poirot himself!

So why on earth would the real killer allow Mrs. Oliver to stick with this solution, especially since every other aspect of the plot proves the efficacy of their influence over her? It’s a minor point, I guess, but it bothers me. Aside from that, the opening scene between Poirot and Mrs. Oliver is fun, and the hook is concise and – as I admitted from my own youthful experience – effective.

Score: 7/10

The Closed Circle: Who, What, When, Where, Why?

Who?

“Poirot blinked and looked at Mrs. Oliver in mute incomprehension. ‘A magnificent Cast of Characters,’ he said politely.”

I’ve mentioned before how biographer Laura Thompson’s denigration of Christie’s writing from 1950 on ruffled my feathers. She describes how, by 1950, Christie’s best work was behind her, and the publication of A Murder is Announced – “set the standard for much of what followed: supremely accomplished, utterly readable, but the product of ‘Agatha Christie the phenomenon, rather than Agatha the writer.”

The 50’s are full of highpoints: four Miss Marple novels, three of which are gems and the fourth (They Do It with Mirrors) full of interesting characters and juicy Marple backstory; the rich darkness of standalone Ordeal by Innocence; and several extremely enjoyable Poirot adventures.

Three out of five ain’t bad! I would suggest that the main evidence of Thompson’s claim of a dip in greatness comes smack in the middle of the decade with the two Poirot novels, Hickory Dickory Dock and Dead Man’s Folly. We’ll get to the former soon enough, but I will say that it has too many interesting aspects to it to dismiss it; even its flaws are interesting! Folly, to me, is duller fare, but it touches, like some of the better novels surrounding it, upon a prevailing theme of Christie’s 50’s work: England’s rapidly changing society.

A Murder Is Announced and After the Funeral dealt with the transformation of British life in a village and a manor house, respectively. Funeral focuses chiefly on matters of place, while A Murder Is Announced poignantly depicts how the ravages of war have affected the population. People are relative strangers to each other in Little Paddocks. In Funeral, we have an extended family, but even they are generational strangers to each other. In Folly, Christie quickly establishes the circle of people who have come together to plan a fête. They seem to work easily with each other, and there are enough intrigues going on – petty jealousies, suggestions of affairs – to suggest that they all know each other well enough.

But in an early conversation with Poirot, civic leader Mrs. Masterton dashes this impression. She is one of the old school in Nassecombe and has known Mrs. Folliat, the previous owner of Nasse House, for years. But the same can’t be said for most of the others in attendance. Sir George Stubbs? “He isn’t even really Sir George – was christened it . . . Rich men must be allowed their little snobberies . . . “Captain Jim Warburton? “Silly the way he sticks to calling himself ‘Captain.’ Not a regular soldier and never within miles of a German.”

In appearance and behavior, both of these men are old Christie “types” that she has stuck into plots again and again. Sir George has traces of Lord Easterfield from Murder Is Easy, and Warburton goes back to Commander Challenger of Peril at End House or Commander Haydock from N or M. Neither Stubbs nor Warburton is as well developed as these or other examples, and while the fact that at least one of these men is a fake (a fact important to the murder plot), we never get to know either one well enough to care much.

The central figure of the book is Hattie Stubbs, one of the most discomfiting characters in the canon. In appearance she vaguely resembles Arlena Marshall, right down to the coolie hat, although while Arlena was an actress, it’s Hattie who seems completely artificial. Overly made up to accentuate her foreign roots, she is repeatedly and uncomfortably described as “a mental defective.” Everyone calls her this, perhaps most insultingly, her own cousin, Etienne de Sousa:

“Oh, it is no secret. At fifteen Hattie was mentally undeveloped. Feeble minded, do you not call it? She is still the same?” When Poirot concurs, Etienne excuses it: “Oh well! Why should one ask it of women – that they should be intelligent! It is not necessary.” Why, indeed? Sadly, we need to add this to the list of small crimes that Christie committed against her own sex.

Hattie spends most of her appearances in the book contemplating her jewels and developing a headache. Her eyes are the most interesting thing about her. When Poirot meets her, he is struck by her “childlike, almost vacant stare.” Later, however, at a pivotal moment, he watches her:

“. . . her eyes came up and cast a swift glance along the table to where he sat. It was a look so shrewd and appraising that he was startled. As their eyes met, the shrewd expression vanished – emptiness returned. But that other look had been there, cold, calculating, watchful. . . .”

Since this look conforms to nothing we have been told about Hattie, I guess you would say that, in retrospect, it becomes, I suppose you would say, a “clue” as to her true nature. Perhaps it would have been a more effective one if the character didn’t disappear from the scene soon after, never to return.

The rest of the characters are, in my opinion, frankly boring. My overall opinion of They Do It with Mirrors notwithstanding, at least Christie has created an interesting set of people, with a complex history centered around the many marriages of Carrie-Louise Serrocold. Even minor characters like the Restarick brothers are recognizable as people. In Folly, we have the Legges, Peggy and Alex, who despite their marital and/or legal troubles, never come to life. Miss Brewis is the latest in a long series of ugly, efficient secretaries who stand up for a murderer. Mrs. Masterton, Captain Warburton, Michael Weyman, and Etienne de Sousa simply can’t be taken seriously as suspects.

That leaves three characters who are more successfully conveyed. Old Mr. Merdle and his granddaughter Marlene Tucker, the two victims of the novel, make interesting cameos. Marlene feels like a 50’s teenager, obsessed with sex and comic books. As often happens when Christie places the murder of a child into one of her plots, most of our feeling for the victim comes from a visit to her family. We saw this in The Body in the Library, and we’ll experience it again in Hallowe’en Party. As for old Merdle . . . while we’ve seen garrulous countrymen like him a dozen times, at least he is given a nasty death and the opportunity to pronounce the central, if weak, clue to the whole business: “There will always be Nasses at Nasse House!”

Amy Folliat is another of those charming older ladies at which Christie excelled. She’s a warmer Mrs. Lorrimer, a kinder Mrs. Inglethorpe, a saner Miss Waynflete. She is also one of another line of characters in Christie: the bad mother – although there is no malevolence or malfeasance in her raising of her children, merely over-indulgence. Yet it’s impossible for me not to cast a lot of the blame for all that happens here to Amy’s inability to reign in her bad seed of a son or to protect her adopted daughter Hattie. I don’t think any of this is developed as well here as it is in other novels, but Amy’s is the most interesting backstory – and the most central to the puzzle plot, such as it is.

What?

The plot leading to the murder in both Dead Man’s Folly and its predecessor Hercule Poirot and the Greenshore Folly can be summed up thusly: Hercule Poirot meets the residents of Nasse House, in Nassecombe (called Greenshore House, in Lapton, in the novella). On the day of the fête, Lady Stubbs announces that her cousin Etienne de Sousa/Paul Lopez is arriving; she is definitely upset about this. During the festivities, the cousin arrives, Hattie Stubbs disappears – and poor Marlene Tucker is found strangled in the boathouse.

The basic problem with the novel from here can be summed up thusly: the murder in the novella occurs at the end of Chapter Seven (out of ten chapters), and Poirot begins revealing the killers and their plot fifteen pages later. In Dead Man’s Folly, the murder occurs at the end of Chapter Six (out of twenty chapters), ands Poirot reveals the truth 110 pages later. The enjoyment of the book rests then on two precepts: is the essential puzzle plot a good one, and is the material that Christie added to transform a long short story into a novel intriguing in and of itself, or does it amount to padding?

I’ll speak about the solution later. As to expansion of the material, I fear I land on the side of padding. In The Greenshore Folly, aside from Sir George and Lady Stubbs, Mrs. Folliat, and Marlene Tucker, none of the characters matter to the plot, aside from creating the sense of community and supplying information to Poirot about the family. This isn’t a fatal blow to a Christie novella: although I prefer a more active circle of suspects, as in The Underdog or Dead Man’s Mirror, Christie has demonstrated charm and cleverness with a smaller cast (Murder in the Mews) or a circle of nice-people-who-aren’t-really-suspects (The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding).

For over a hundred pages, we follow Poirot as he considers Mr. de Sousa, Miss Brewis, and Alec Legge for the role of murderer. As none of these characters has particularly come to life for us, it’s hard to take their potential culpability seriously. I’m trying to remember who I suspected when I first read this. I want to say that it was Mrs. Folliat, committing the crime to save the reputation of her beloved family. In the end, I needn’t have wasted my time.

When and where?

The pleasure of being treated to a scenic tour of one of Agatha Christie’s favorite residences cannot be overestimated. As I mentioned earlier, it was great fun touring Greenway and visiting the sites of various nefarious activities that I grew up with. Standing in the boathouse or on the battery, gazing out over the gorgeous River Dart, was inspiring. Every room was decorated but not in a pristine fashion; rather, it felt lived in, as if Agatha or Max could walk in the door at any minute. And, since our visit coincided with Christie’s birthday, there was even a small fête going on when we got there; unfortunately, the celebration seemed to be petering out when we arrived on the green, and what we saw was nothing compared to the fête at Nasse House as described in Chapter Six. (But I did get to sample some mighty good cider!)

Some of the puzzle plot depends on geographical factors and is a matter of societal interest that Christie explored in her 50’s fiction. In After the Funeral, one of the major events hanging over the heads of the Abernethie clan is the inevitable sale of the family home and its probable transformation into a hotel, home for refugees, or other commercial venture. Poirot takes advantage of this by going undercover as a potential buyer for the fictional UNARCO. By the time of Folly three years later, that sort of sale is a done deal: the house next door to Sir George Stubbs is now a hostel for foreign travelers, a situation of which the killers take full advantage.

And while the whole of the novel takes place in this single spot over the course of several months, Hercule Poirot traverses it quite a bit, traveling around the house and grounds, with its many gardens, to the tiny lodge where Mrs. Folliat lives, and of course the river and boathouse, where poor Marlene and her grandfather both meet their ends. The only thing you will find no sign of in your tour of Greenway is a folly, but then its presence, noted at the start by architect Michael Weyman for its unsuitable placement, is another major clue.

Score: 6/10

The Solution and How He Gets There (10 points)

Out of sixty-six novels, one of the most oft-used tropes (I count thirteen examples, but an argument could be made for one more) is the Diabolical Couple, who sometimes present themselves as strangers, or at odds with each other, but sometimes not, and who often provide alibis and other material to cast suspicion away from each other. Christie must be applauded for the variety she mines out of this technique, but if you think about it, the set-up for Dead Man’s Folly has essentially been seen before (in an early 40’s novel) and will be seen twice again in the 1960’s. All four instances have their problems for me, but at least they’re different problems. Here, I think the issue is that the truth – that James Nasse survived the war, married a wicked Italian girl, came back to England and claimed his family home under a new identity, got his mother to arrange his marriage to wealthy but stupid Hattie, killed her right after the wedding and switched out his actual wife, who then spent years pretending to be Hattie, and then had to kill Marlene Tucker and her grandfather because they threatened to expose the truth of the first wife buried under the poorly placed folly, all while his own mother lived right on the grounds and did nothing about it – all of this is only tangentially clued. Why did a man of such good taste as Sir George choose a poor setting for the folly? What did Old Merdle mean about there always being Nasses at Nasse House? What could explain some of Mrs. Folliat’s vague statements about the missing Hattie that seemed to refer to two different people? It comes together in the end, but as a puzzle plot? Not so much.

Which means that Hercule Poirot’s task is to take all of this in and make sense of it without having much to guide him. In that manner, he performs his job much as Miss Marple performed hers – with an understanding of human nature and a lot of lucky guessing. The savvy reader will probably be ahead of Poirot here, as it’s hard to be taken in by the old chestnut of Sir George engaging his wife in “conversation” by standing at his balcony and shouting to her unseen presence inside, all in order to establish an alibi for her. While “Hattie” is fond of oodles of make-up, there is nothing to suggest she has the ability to play different characters – except the insinuation that her eyes betray a greater intelligence than what she presents.

And that’s all there is. When Poirot delivers his solution, appropriately enough, to Mrs. Folliat alone, (who else in this cast any sort of personal stake in this affair?), he offers a straightforward narrative as to what happened, without any real clues to support it. This makes his few references to his own thick-headedness a rare example of Poirot being a little hard on himself. That he got everything so right with so little evidence is actually something of a miracle.

Score: 5/10

The Poirot Factor

How can you not love Hercule Poirot appearing on Page One and never leaving the scene until the final words on Page 178? He displays a generosity of friendship to Mrs. Oliver that is nice to see, and a kindness to Mrs. Folliat at the end that I’m not convinced she fully deserves. (I might bring her up on charges as an accessory after the fact to the real Hattie’s murder.) Poirot is never less than charming, and since his sleuthing amounts more to physical activity and semi-logical guesswork than to any intellectual application of those little grey cells to actual clues, he comes across more as a miniature Philip Marlowe . . . or maybe, more appropriately, a tinier, more humane Holmes. Naw – he’s Poirot all the way. I just wish that the case had been a better challenge for his, and our, sleuthing skills.

Score: 6/10

The Wow Factor

Aside from Christie setting the book at her summer home, I don’t see much to “wow” about here. In fact, there’s something of a negative wow in that this is one of those novels Christie expanded from a shorter work. None of these that I can recall – The Mystery of the Blue Train, Dumb Witness, or Sparkling Cyanide – was improved upon by expansion.

Score: 4/10

FINAL SCORE FOR DEAD MAN’S FOLLY: 28/50

THE POIROT PROJECT RANKINGS SO FAR . . .

- The A.B.C. Murders (46 points)

- Cards on the Table (36 points)

- Dead Man’s Folly (28 points)

- The Mystery of the Blue Train (26 points)

Next time . . .

We return to the 1930’s . . . and to a title certain to include a hefty discussion about motive!

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX (The Blog-iography!) | Ah Sweet Mystery!

We didn’t plan well enough to get to visit Greenways, darn it!

Next time.

IIRC correctly the novel (and not the movie versions), I thought Poirot let Mrs. Folliat off too easy. She was an accessory every step of the way, leading directly to the deaths of Old Merdle and Marlene Tucker.

But peasants don’t matter compared to their betters.

The Ustinov film provided a very nice clue to Poirot when he visited Mrs. Folliat. Her walls, which should have been plastered with proud family memorabilia dating back hundreds of years, were bare.

LikeLiked by 3 people

It has been many years since I saw the Ustinov film because, as much as I love Jean Stapleton, she is NOT Ariadne Oliver. But that is a clue worthy of Christie herself!

LikeLike

I wasn’t thrilled with the Ustinov version.

Then I saw the Suchet version, normally the gold standard.

And Ustinov edged him out!

Shocking, I know but it all came down to the ending for me. Mrs. Folliat got a pass and the Tucker family didn’t get the justice and acknowledgement of a public trial.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I liked the shorter “Greenshore” version as well. I read it for the first time last month. It is not really a Christie book which gets a lot of press.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s astonishing to me that it took so long to publish the novella after Christie’s death. But then I think of the dog’s ball story that John Curran unearthed – which is just as good as Dumb Witness – and it all makes some kind of nonsensical sense.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps the fact Greenshore is so similar/identical to Dead Man’s Folly might have put them off?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good point! “The Affair of the Dog’s Ball” has a different solution. This novella is almost identical and might have pointed out what, to me, are the novel’s weaknesses.

LikeLike

Thanks for this detailed breakdown.

I think I have read this. “There will always be Nasses” rang a bell. However, when you first started describing it, I was thinking of Hallowe’en Party, which I remember much better.

I think I would have enjoyed this despite all the flaws you describe. I’ll even read padding by Christie. The characters might be stock, but they are stock *English* characters from the 1950s, which is so far from my experience that reading Christies as a teenager was truly a cross-cultural experience. Same for the setting. What even is a folly? It was all new to me, and I loved it, and I was just along for the ride. I didn’t know enough about English social realities to solve the puzzles even if I had wanted to.

Have you read anything by Andrew Klavan? One thing I appreciate about him is that he often features sleuths who are very intuitive, like Miss Oliver, and they get a hunch but can’t explain exactly why, which is frustrating to them. In A Strange Habit of Mind, Cameron Winter is described as going into a “fugue state,” during which his not-exactly-conscious solves puzzles. Hard to imagine that this served him well as a spy, but … ya know. I think you would enjoy Klavan if you haven’t read any yet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know his name, but I’ve never read Klavan. We studied English literature at the same time at U.C. Berkeley, a huge department where I managed to make friends with no one. (I spent every moment I could in the Drama Department.) We were two liberal Jewish boys whose lives couldn’t have taken more opposite paths. He became a devout Christian conservative, and I . . . didn’t. I envy him his writing success, while I did other things. Can you recommend a title that pretty much sticks to traditional detection?

LikeLiked by 1 person

He has a lot of novels that he wrote before his Christian era. They tend to be more hard-boiled-detective thrillers than drawing-room puzzle mysteries, but they are usually twisty and have a number of subplots going on. He likes stories where the protagonist has reason to doubt his own mind. The script for Don’t Say A Word was written by him, from one of his novels.

As I looked up his books, I realized there’s a lot of his body of work that I haven’t read yet. But for 100% crime, no paranormal stuff, I recommend Damnation Street and Identity Man. If you can put up with some paranormal stuff, I loved Werewolf Cop. Especially the title.

His most recent Cameron Winter series was actually what I had in mind when I wrote my original comment, though. That’s: When Christmas Comes, A Strange Habit of Mind, The House of Love and Death, A Woman Underground. All of those are thrillers with a sleuth who used to be a spy and is now an English professor. Small world, eh?

Sorry so long. tl;dr : Damnation Street, Identity Man

LikeLike

“But in the end, Dead Man’s Folly was an experience that this voracious young Christie fan had expected: it was dull.” If you do mean that you expected it to be dull, OK. But it seems as if there’s a “never” missing before “expected.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

How can that be?!? I make that mistake – I mean, I NEVER make that mistake . . . er, it’s fixed!! (Thanks!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #5: Three-Act Tragedy | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #7: Death in the Clouds | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #8: The Big Four | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #9: The Murder of Roger Ackroyd | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #10: Murder in Mesopotamia | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #11: Hickory Dickory Dock | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #12: Elephants Can Remember | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #13: Hallowe’en Party | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #14: Death on the Nile | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #15: Peril at End House | Ah Sweet Mystery!