“I am only stranger, passing through, and it has been well said, the traveling dragon cannot crush the local snake . . . Do not believe, however, that I consider myself dragon. I lack, I fear, the figure.”

Once upon a time, a hundred years ago to this very day, the The Saturday Evening Post began a serialization of the latest novel by Earl Derr Biggers, an author whose popularity for books like Seven Keys to Baldpate had been boosted by successful adaptations to stage and/or screen. This latest work, The House Without a Key, introduced a character who, to my knowledge, was the first Asian-American detective in fiction and who, despite appearing in only six novels over the course of seven years, would maintain a huge popularity due to a series of films that ran from 1926 to 1949.

The Charlie Chan books were not only a general success but a boon for the people of Hawaii, a territory that had had statehood on its mind since its annexation to the United States in 1898. Biggers’ feelings for the land and its people were evident on every page, as was a sense of authenticity in his descriptions of geography and customs. In April 1925, the Hawaii Tourist Bureau expressed its appreciation by sending a large key to Biggers, inscribed thusly: “Hawaii is still the House Without a Key; you have it. Use it often.”

Author Yunte Huang (Charlie Chan, 2010) points out that, as well received as the book was, it also faced criticism over its portrayal of a Chinese detective, particularly his manner of speaking in pidgin English. Biggers published his response in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin:

“I am sorry if Honolulu is still distressed by Charlie Chan’s way of putting things. As I told you, if he talked good English, as he naturally would, he would have no flavor . . . In this dilemma, I turned to the way the Oriental mind sometimes works when its owners take pen in hand.”

On the one hand, this is no different from making Hercule Poirot a punctilious Belgian, or reducing any sleuth to a series of “qualities” like knitting needles and a chronic cough (Miss Silver) or beer and orchids (Nero Wolfe). Charlie Chan is also obsessed with his weight and has a propensity for playing matchmaker for a pair of worthy youngsters. But Biggers’ claim that he understands “the way (of) the Oriental mind” is a problem, and I have to say after reading my first Charlie Chan novel that it struck me how effortful it must have been for Charlie to speak constantly in aphorisms and how aware he must have been of the effect it had on others. One can only wonder if Biggers might have softened this aspect of Charlie’s character had the series continued for many years of social change. Unfortunately, a year after the sixth novel was published, Biggers died of a heart attack at the all-too-young age of 48.

No matter how problematic the depiction of the character may be, (and as we will see in the future, he is more problematic in the films), Charlie Chan was neither written nor portrayed as a figure of fun. And while that doesn’t excuse the issues of casting or the way Chan spoke and carried himself in these representations, Charlie deserves to be considered, even as a starting point for a larger discussion, as one of the few depictions of an Asian hero found in early 20th century American culture. And for mystery fans, his hundredth anniversary must be celebrated.

Thus, the first thing that I did after doing some research on the creation of Charlie Chan was to turn to Biggers’ work itself. On advice of counsel, I chose not the first, but the sixth and final novel that Biggers wrote, 1932’s Keeper of the Keys.

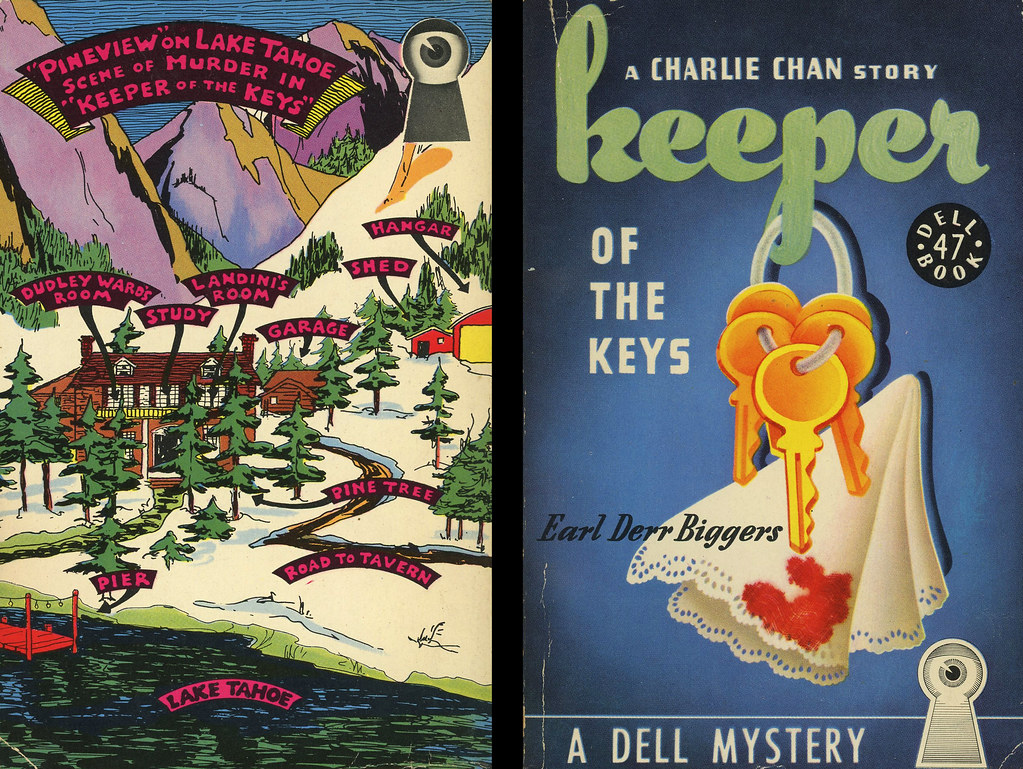

The novel is set in California rather than Hawaii. Charlie has been finishing up a case in San Francisco when he receives a request from tycoon Dudley Ward to hop a train up to Ward’s estate in Lake Tahoe and conduct some sensitive business for him. Eighteen years earlier, Ward had been married to a young opera singer named Ellen Landini. As her star took off, their marriage floundered, and Ward has recently learned of the possibility that Ellen was pregnant when she left, that she gave birth to a son, and that she gave him away to wealthy friends.

Now Ward wants to locate that son and make him his sole heir, and to do this, he has resorted to drastic means. He has invited ex-husbands #2 (a sullen miner) and #3 (a conniving vocal specialist), and soon to be ex-husband #4 (an Italian opera conductor) to the house. Soon, Landini herself arrives with her latest beau, (a much-too-young opera singer), his lovely sister, the ex-chauffeur-turned-pilot who broke up marriage #3, and the pilot’s jealous French wife, who now serves as Dudley Ward’s maid. To round out the list, there’s Ah Sing, Ward’s elderly Chinese servant, fiercely loyal to his employer and so trusted that he is – wait for it! – the keeper of the keys!!!

Just before Landini is set to leave Ward’s house and return to Reno, a shot rings out. All the guests rush up to the star’s room to find that she has been shot to death. Charlie is asked to help but reminds his host that he has no authority in California. Fortunately, Lake Tahoe has just elected a wet-behind-the-ears sheriff named Don Holt, whose father had held the job for fifty years before he went blind. Don understands his own limitations well enough to beg Charlie to take charge, and a lovely, albeit one-time-only, partnership begins.

In its structure, Keeper of the Keys fulfills the promise of a traditional Golden Age mystery. The victim first appears as an appropriate combination of the alluring and the despicable, and then, like Arlena Marshall in Evil Under the Sun, is revealed to have a wholly different character. The setting is appealing: winter in Lake Tahoe fascinates Inspector Chan, who is excited to leave the sun-drenched beaches of Honolulu behind for the bracing cold. The closed circle is not particularly exciting, but the characters are distinct from each other. Biggers spends more time on the budding romance between the young Sheriff and the opera singer’s sister than either Knox or Van Dine might prefer, but both characters make for charming company.

There are all manner of clues, including one of the most commonly used clues in classic crime fiction: I spotted its significance immediately, but Biggers applies ultimately it with great subtlety. There is a second murder that is as well-staged as the first. And the solution, while it probably won’t surprise mass consumers of detective fiction, may have seemed a bit more twist-worthy at the time and does lead to us having to rethink certain facts and events in an interesting way.

Ultimately, the most interesting thing for me was spending time with Charlie Chan. In so many ways, of course, he is the traditional Golden Age detective, a combination of brilliant mind and amusing character tics (the aphorisms, the obsession with his weight). Like a number of sleuths in the early years of the 20th century, he eschews the modernization of his craft for a focus on human nature. He says this many times, most clearly in an early conversation with the sheriff:

“I ain’t never had no use for science – the world was gittin’ along a whole lot better before science was discovered.”

Charlie smiled. “You mean, fingerprints, laboratory tests, blood analysis – all that. I agree, Mr. Holt. In my investigations of murder, I have thought, always, of the human heart. What passions have been at work – hate, greed, envy, jealousy? I study always – people.”

That’s all well and good, but matters of ballistics and other scientific “wonders” do play their part here!

What I didn’t realize – and what makes this reading experience even more rewarding – was that, unlike the films, Biggers did not ignore the matter of Charlie being Chinese-American, and the implications it had on how he presented himself. This is keenly observed in the relationship between the Inspector and Dudley Ward’s servant, Ah Sing. If Charlie’s English is broken, it’s nothing compared to the patois that Biggers applies to the servant’s manner of speech. One could casually dismiss the exchange of “l” for “r” and weird pronouns as stereotypical, but Ah Sing turns out to be so much more than the way he speaks in the book.

The elderly servant is much beloved by the locals who grew up with him, and his loyalty to them is portrayed in a complex manner. At one point, Charlie is asked why he is having so many problems getting the truth out of the servant, since they are both Chinese, and Chan gives a powerful explanation:

“It overwhelms me with sadness to admit it, for he is of my own origin, my own race, as you know. But when I look into his eyes, I discovered that a gulf like the heaving Pacific lies between us. Why? Because he, though among Caucasians many more years than I, still remains Chinese. As Chinese today as in the first moon of his existence. While I – I bear the brand – the label – Americanized. . . . I traveled with the current. I was ambitious. I sought success. For what I have won, I paid the price. Am I an American? No. Am I, then, a Chinese? Not in the eyes of Ah Sing. But I have chosen my path, and I must follow it.”

Biggers does not dwell on the racism experienced by Chinese people in America, but he does not ignore it either. At one point, Ah Sing is assaulted by person or persons unknown, and Biggers provides this commentary:

“What was behind this unprovoked attack on Sing? Or was it unprovoked? Did Sing know who it was that had struck him? If so, – why should he hide it? Fear, no doubt, fear of the white man inspired in the old Chinese of mining-camp days by years of rough treatment and oppression.”

This is only guesswork on my part, but the relationship between Charlie and Ah Sing may be the reason why Keeper of the Keys is the only novel that was never adapted to film. Sadly, classic Hollywood had no interest in exploring the real lives of Chinese people, in America or otherwise, or in honest depictions of the dynamic between Chinese and Caucasian Americans. It would be impossible to play the subservience card here, as the films tended to do. Still, reading this novel makes me want to explore further at some point; I recently read that some consider the fifth novel, Charlie Chan Carries On, to be the best. Who knows when I’ll get there?

However, I will have a lot to report on the films in the near future. And before that I’ll also be looking at a near-contemporary of Charlie Chan’s – another Asian-American detective, and a female one, to boot!

Stay tuned.

I am glad that you enjoyed this novel, Brad, as complex as it may be to navigate today. Keeper of the Keys is not one of the Chan novels I have read. When I was a young, naive Charlie Chan obsessive, I read the first three books in the series and now, in honor of Chan’s centenary, I have returned to Biggers’ work and read Charlie Chan Carries On and I am about 2/3 of the way through The Black Camel as I type this comment. Biggers has many deficiencies as a writer (I personally think his characters are pretty paper-thin and, with 17 suspects to contend with in CCCO, it is almost impossible to keep them all straight), but the books are compulsory reading. I am enjoying Black Camel a lot; it is a complex book and very ambitious. I cannot wait to share my insight when you, Sergio, and I embark upon our ultimate folly in just a few weeks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That huge character count affects my enjoyment of the film adaptation as well (Charlie Chan’s Murder Cruise). The plot needs more than 76 minutes to develop all these people. We’ll talk about all this when we draft; I don’t want to give too much away!

LikeLike

It’s been too long since I read the Chan books. I *feel* like in at least one, he hints or admits his speech is a pose or at least partly so to disarm others, but I may be conflating it with Poirot’s confession of using that same tactic (at the least, in the unlikely event anyone tackles ol’ Charlie again, that would be one way to approach it if they didn’t modernize him entirely, a crafty man playing up the stereotyped expectations, which I think whether the books said so or not, is a valid reading of literary Chan). My copy of Huang’s book is in storage, but it’s amazing in terms of research, covering Chang Apana, and getting an approach to the books and the character by an actual Chinese person.

I actually still have a soft spot for the movies at their best (which… admittedly isn’t a lot of the time), and even the Monograms thanks to one of my heroes, the always funny Mantan Moreland (though of course they overdo his scared act in some of the entries, they also refer to him usually as “number two assistant” rather than a servant, which at the time is something)! There’s a classic bit on Jay Ward’s FRACTURED FLICKERS series from the sixties, where host Hans Conried talks to Roddy McDowall about the cost of CLEOPATRA, and Hans claims INTOLERANCE was the most expensive movie ever made at one million dollars (or whatever). Roddy says for that amount today, “you couldn’t even make a good Charlie Chan movie.” Hans reply, “Well, no one ever *has*!”

I remember enjoying MURDER CRUISE but not comparing it with the source book (which I’m not sure was in my collections, which *did* have THE BLACK CAMEL and HOUSE WITHOUT A KEY). Mainly because the cast had so many actors who specialized in sinister types (Lionel Atwill, Charles Middleton, Leo G. Carroll, Leonard Mudie, etc.), I was surprised by the culprit not because of the plotting or clues but because *any* of them would have been credible!

I heard a 1957 radio episode of CBS RADIO WORKSHOP, an anthology which I love, but this outing had two American tourists going to Hawaii (still not a state yet), and the Hawaiian characters (all played by white people) speak *sub* Chan pidgin. It’s agonizing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So glad you had a positive experience with the book – this is the one I remember best (been at least 3 decades since I read a Chan novel).

LikeLiked by 1 person