Three-Act Tragedy is the first of nine Poirot novels to appear back-to-back in the latter half of the 1930’s. (Between 1931 -38, there were twelve in total.) It was an extraordinary decade for the Belgian detective: he traveled across Europe on the Orient Express and on a steamer down the Nile, with side trips to Mesopotamia and Syria. Every vacation he took became a busman’s holiday, and he came across nearly every twist ending in the book! Everybody did it! Nobody did it! His client, The most likely suspect, the police inspector, , Poirot’s own client – nobody was safe from suspicion!

Three-Act Tragedy shares a number of features with other titles of the period: like Peril at End House (1932), it begins in Loomouth, Cornwall and includes the delivery of a box of poisoned chocolates; it shares a theatrical setting with Lord Edgware Dies (1933) and doubles down with an actor’s masquerade at a dinner party as part of the murder plot; it shares the trope with Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? (1934) of a servant being a central feature of the case, and both novels contain a scene where a character fakes an automobile accident outside a manor in order to gain entrance; and it is the first of the 30’s novels to incorporate a team of investigators, a trope that is repeated in Death in the Clouds, The A.B.C. Murders and Cards on the Table. (And in three of these four novels, the killer turns out to be a member of the team.)

Then what sets Three-Act Tragedy apart from the rest of the pack? For one thing, it trades in the conventions of classic detective fiction in a different way. “Theatricality” suggests artifice, and the book doubles down on that quality by having a murderer who manipulates classic tropes to achieve his goals. For example, a central feature of the plot is that the main suspect in the central murder is that old standby, the butler. And yet the investigators don’t want the butler to have dunnit. And why?

“Mr. Satterthwaite did not finish his sentence. He had been about to say that if Ellis was a professional criminal who had been detected by Sir Bartholomew and had murdered him in consequence the whole affair, would become unbearably dull.”

Two other related distinctions come to mind, both stemming from the issue of motive. The first is the unique motive for the first murder and, to a lesser degree, the third. The second is that, for reasons that Christie herself apparently could not remember, she changed the killer’s motive from its initial U.S. publication to its U.K. printing. The Brits and the Yanks have been reading different versions of this book for years!!

In America, madness was the condition that prompted the culprit to kill – and it makes sense, particularly considering those outrageous motives, which disregard the value of life so much as to seem . . . well, crazy. In Murder in the Making, John Curran suggests that this is “by far the more compelling” motive. But as I pondered this 4th or 5th re-read of the novel, I found myself disagreeing with John on this point. It’s the other motive, which involves a British point of law regarding marriage, that raises the importance of the novel and sets it apart all the more from any other.

Then there’s the issue of the title. In America, which unusually had the earlier publication date, the book was called Murder in Three Acts. Most U.S. publishers preferred straightforward words like “murder,” “death” and “kill” to loftier ideas, like “tragedy.” But this novel is a tragedy in three acts. The first title (and its attendant condition of madness) makes for a far more prosaic crime novel than what U.K. citizens picked up in 1935. And here I emphasize the word “novel,” not over “crime” but, in this case, right beside it.

Of course, contemporary critics of the author evaluated it as a mystery. The critic Edward Powys Mathers, a.k.a.”Torquemada” summed up the general opinion in his review for The Observer: “Three Act Tragedy is not among this author’s best detective stories; but to say that it heads her second best is praise enough. The technique of misleadership is, as usual, superb; but, when all comes out, some of the minor threads of motive do not quite convince.”

In her Sunday Times review, Dorothy L. Sayers barely mentions the mystery, reserving her praise for the charms of Hercule Poirot. But she ends her short commentary with these words: “Indeed, when Mrs. Christie is writing at the top of her form, as she is (here), all her characters have this reality . . . However surprising or enigmatic the behavior, we believe that everything took place just as she says it did because we believe in the reality of the people . . . This is the great gift that distinguishes the novelist from the manufacturer of plots . . . Mrs. Christie has given us an excellent plot, a clever mystery, and an exciting story, but her chief strength lies in this power to compel belief in her characters.”

Three-Act Tragedy is certainly a clever mystery, with an impossible crime trick (performed twice), a shocking pair of motives, and a surprise killer. I imagine the surprise was even more stunning in 1934/5. For most of its length, however, it is also a love story, and as much of the suspense, comedy and emotion found here is generated by the relationship between the romantic protagonists as it is by the mystery they investigate. And because of that, in the end this book is a tragedy – maybe not as rich and mature as we find in the 1940’s mysteries like Five Little Pigs and The Hollow, but a moving tragedy nonetheless.

And while Christie didn’t write nearly enough about her books, I have to assume that she meant for us to feel this way. My “clue” is that no characters come to life nearly as well as our central quartet of Sir Charles Cartwright, Lady Hermione “Egg” Lytton-Gore, and Mr. Satterthwaite. That is how I felt about the novel midway through this re-reading, and that is what affected my rankings.

* * * * *

The Hook

Before we get to the book proper, Christie gifts us with a special announcement in the form of a “program note”: Directed by Sir Charles Cartwright, Assistant Directors, Mr. Satterthwaite and Miss Hermione Lytton-Gore, Clothes by Ambrosine Ltd., Illumination by Hercule Poirot.”

This playful opener is audaciously clever, for reasons that those familiar with the book will immediately recognize. The reason I mention it right off the bat is that it imbues the novel with a great sense of fun – and fun is what Three-Act Tragedy provides right up through the final line. The novel is divided into three sections – acts, of course – and the first, “Suspicion,” hooks us good and proper in its five short chapters. We are plunged into a vibrant setting – Loomouth in Cornwall – and to Crow’s Nest, the modern bungalow of retired actor Sir Charles Cartwright. We are made acquaintance with the fourteen people who will attend a cocktail party at the actor’s home, a lively mix of show people from the city and a few locals. To our delight, the guest list includes Mr. Satterthwaite, that charming observer of humanity, on loan from Mr. Harley Quin.

A last-minute addition to the gathering is the famous detective Hercule Poirot, described as a “rum little beggar. Rather a celebrated little beggar, though,” and “the most conceited little devil I ever met.” Sir Charles’ oldest friend, the noted nerve specialist Sir Bartholomew Strange, shares his theory “that events come to people – not people to events,” and he wonders, only half-jokingly, if the presence of a famous detective will result in a crime being committed over the weekend. Sir Charles isn’t helping matters with his guest list – more specifically, the number of guests:

“’In that case,’ said Mr. Satterthwaite, ‘perhaps it is as well that Miss Milray is joining us, and that we are not sitting down thirteen to dinner,’

“’Well,’ said, Sir Charles handsomely, ‘you can have your murder, Tollie, if you’re so keen on it. I make only one stipulation – that I shan’t be the corpse.’”

By the end of Chapter Two, Strange’s fears are realized, as death comes for one of the guests. But despite the suspicions of murder that Sir Charles voices, neither Strange nor Mr. Satterthwaite, not even Poirot himself, seem suspicious. First of all, the victim is the local parson, Reverend Babbington, a mildly infirm old man with a sweet, gentle nature and not an enemy in the world. An examination of the body and the man’s cocktail glass yields nothing. Case closed, right? Except Sir Charles can’t help wondering. And his suspicions are shared by Lady Hermione Lytton-Gore, known hereafter as “Egg,” one of Christie’s most delightful heroines, who shares Sir Charles’ opinion for reasons of her own.

The section ends in a way that connotes its title – “Suspicion” – with a strong frisson of tension: Charles has departed Crow’s Nest, never to return, on account of his seemingly unrequited affection for Egg; Egg is furious because her plan to snare Sir Charles has backfired; and ten other people go their separate ways, little knowing that the death of Reverend Babbington is merely the harbinger of more terrible things to come.

Score: 10/10

The Closed Circle: Who, What, When, Where, Why?

Who?

The central trio of investigators who occupy most of our attention are beautifully rendered. And in Sir Charles Cartwright, Christie has created one of her best characters. We all know how she felt about actors. (Cue the alarm from All About Agatha.) Only a year earlier, Christie had published Lord Edgware Dies, and the parallels to this novel are obvious. Jane Wilkinson is a very different sort of personality to Sir Charles, but they share the same utter lack of morality, that sense that anything is allowable, even murder, if it paves the way for one’s own success. And, most importantly, both culprits are murdering for love: since they cannot divorce one spouse to obtain another (a situation to Christie would return in the late 50’s), they have no recourse but to kill, again and again and again.

The biggest difference is in our perspective of these characters. While Jane Wilkinson is “the most likely suspect proved innocent,” Sir Charles Cartwright is essentially the protagonist of the novel. Poirot is conveniently pushed to the sidelines through much of the book, and Sir Charles takes on the role of sleuth, playing the part of “that mastermind of the Secret Service,” Aristide Duval, a name that can’t help but remind us of another Gallic sleuth.

Both Sir Bartholemew Strange and Mr. Satterthwaite note that role-playing is a natural part of the man’s make-up. At the start, Strange observes:

“I’ve known Charles since he was a boy. We were at Oxford together. He’s always been the same – a better actor in private life than on the stage! Charles is always acting. He can’t help it – it’s second nature to him. Charles doesn’t go out of a room – he ‘makes an exit’ – and he usually has to have a good line to make it on.”

We mostly see the man through the keen observational powers of Mr. Satterthwaite, another of Christie’s best series characters who makes one of only two appearances in a Poirot mystery (the other is the novella Dead Man’s Mirror). As a personal preference, like my Watsons intelligent and droll, like Satterthwaite, rather than a loyal doofus like Captain Hastings. This “dried up little pipkin of a man . . . a patron of art and the drama, a determined but pleasant snob” is sharp as a tack and contributes much to the investigation, even if he isn’t programmed to see the solutions ahead of others.

Throughout the book, Satterthwaite observes Sir Charles playing one role or another, switching between “Commander Vanstone”, a retired man of the sea and “Aristide Duval”; Satterthwaite even notices that as “Duval,” Sir Charles unconsciously appropriates the slight limp he used playing the role onstage. Only toward the end do we discover that “Sir Charles Cartwright” himself is a construct, put together by an ambitious man named Mugg.

This is Christie at her best! She is parading before us a man who never plays an honest version of himself, and then she dares us to interpret that fact correctly. Her most audacious use of this occurs when Cartwright and Satterthwaite are looking into the disappearance of Ellis, Sir Bartholomew Strange’s temporary butler and the main suspect in the doctor’s murder. Sir Charles drags Satterthwaite back to the man’s rooms to investigate the significance of an ink stain on the floor, and the older man watches the actor think:

“Charles Cartwright had become Ellis the butler. He sat writing at the writing table. He looked furtive, every now and then he raised his eyes, shooting them shiftily from side to side. Suddenly he seemed to hear something. – Mr. Satterthwaite could even guess what that something was – footsteps along the passage. The man had a guilty conscience . . . ’Bravo,’ said Mr. Satterthwaite, applauding generously. So good had the performance been that he was left with the impression that so and only so could Ellis have acted.”

Since Sir Charles kills three times for the love of a woman, it’s important that the lady be worthy. And Lady Hermione “Egg” Lytton-Gore is the other triumph of this book, an “Elaine” worthy of her aging Lancelot. Throughout the story, everyone raises their eyebrows and then smiles indulgently at how men in their fifties develop mad passions for girls in their twenties. But Christie does everything in her power to make us root for this pair, even going to far as to make the requisite younger swain (which Christie always supplies so that the leading lady won’t be alone when her “one true love” is carted off to jail), Oliver Manders, both attractive and – gasp! – a Jew.

Sir Charles, Egg, and Mr. Satterthwaite command our attention throughout, like a romantic comedy-mystery with a glamorous couple and their aged duenna. The problem is that we’re not supposed to suspect any of them of the killings of Reverend Babbington, Bartholomew Strange, and Mrs. de Rushbridger, and so Christie supplies a list of “suspects” for us to consider.

These characters appear at the top of the novel, attending the cocktail party where Babbington dies. And then, since nobody believes Sir Charles’ assertion that the Rev has been murdered, these folks disappear for over a hundred pages. We know that most of them attended the fatal dinner at Strange’s manor, but we get little more than impressions about them from the servants.

They’re not bad characters: Christie supplies impressive sketches of them all, although we have seen most of them before and will see them again. Angela Sutcliffe, the aging actress (shades of Linda Arden and Carlotta Adams), Cynthia Dacres (Rosamund Darnley without the warmth), Freddy Dacres (yet another portrait of Monty Miller), Miss Milray, the ugly secretary/housekeeper (like a dozen women from Miss Lemon onwards), and so on. The most interesting of these, perhaps, is Anthony Astor, a.k.a. Muriel Wills, another woman writer whose observational skills rival that of a detective – and nearly cost her her life. And the nicest of them is Egg’s mother, the kindly and impoverished Lady Mary. Bad mothers tend to outweigh the good ones in Christie, so it’s nice to see such a lovely mother-daughter relationship. (Shades of Agatha and her own mom? Who can say???)

Although this circle of suspects is mentioned frequently, their actual page time is relatively brief. I can’t help thinking that if Christie had put a bit more into these secondary characters, the solution would seem less obvious. But then I’m speaking after years of acquaintance with this book and multiple readings. Plenty of people have been surprised by the ending, myself included!

What?

The 1930’s saw the Golden Age of Detection in full flower. Those who hate traditional mysteries for their artifice can wave novels like this one in the air as evidence of their own sour theories of literature. Conversely, those of us who love that artifice can embrace Three-Act Tragedy as Grade A stuff. The situation is one of Sir Charles writing and performing – executing as it were – a Golden Age mystery of his own. That he has included both Poirot and Mr. Satterthwaite, who have sleuthed before, in his game is deliberate, and it allows for some delicious meta-fiction moments. My favorite is when Sir Charles and Mr. Satterthwaite are investigating the possibility of Ellis’ guilt in the murder of Sir Bartholomew Strange. This would mean that “the butler did it,” and Mr. Satterthwaite’s heart sinks at how boring this truth would turn out to be. As it turns out, Sir Charles takes pity on the man (and the reader) by recasting Ellis as a blackmailer rather than a murderer.

But bear with me here: even though we’re smack dab in the middle of a mid-30’s puzzle plot, at the heart of this mystery novel lies a love story, one that you would find in films throughout the Golden Age; that of a sophisticated man of the world thrown together with a vibrant but inexperienced girl. Let me remind you that the third of S.S. Van Dine’s Rules, published in 1928, expressly forbids this: “There must be no love interest in the story. To introduce amour is to clutter up a purely intellectual experience with irrelevant sentiment. The business in hand is to bring a criminal to the bar of justice, not to bring a lovelorn couple to the hymeneal altar.” Agatha Christie tends to reserve romance for her thrillers and Tommy and Tuppence. Her lovers are just as likely to end up on the dock as at a chapel by book’s end.

But that doesn’t seem to be the case here. We have successful actor Sir Charles Cartwright, newly retired and settled in his sophisticated bungalow in Loomouth, and Egg Lytton-Gore, striking, restless, impoverished. Her social life had been taken up with “boys,” specifically that Jewish Leftist Oliver Manders, but now she has fallen hard for an older man. Today we might find the thirty-year age difference a tad creepy; back then, it was considered a “good marriage.” Lady Mary, Egg’s mother, sees in Sir Charles a chance for her daughter to escape an impoverished and dull village life – and to rid herself of Oliver, a dangerous young man because he has ideas! Mr. Satterthwaite presses Lady Mary on the topic:

“’All the same, Lady Mary, you wouldn’t like your girl to marry a man twice her own age.’

“Her answer surprised him.’ It might be safer so. If you do that, at least you know where you are. At that age, a man’s follies and sins are definitely behind him; they are not – still to come . . .’”

The fact that Hercule isn’t around much suggests that here is a couple who have little need for “Papa” Poirot. Solving the mystery will by necessity throw them together and ultimately banish all obstacles to love. We see how Egg uses the situation to get closer to Sir Charles, how she bristles at the presence of a chaperone like Mr. Satterthwaite, how both Mr. S. and Poirot seem to give their blessing to this May/December union. Satterthwaite is determined to prove Oliver Manders guilty of the crimes, while Poirot lays aside his own vanity and assures Satterthwaite that even if he finds the solution, “Sir Charles must have the star part. He is used to it. And, moreover, it is expected of him by someone else.”

The only person who seems to be sensible here is Sir Charles himself. Sensible as to murder, as all mystery heroes are, and sensible to the wrongness of his romance with Egg. After Babbington’s death, he absents himself from the scene, sells his bungalow and repairs to Monte Carlo. It works as a plot twist in either genre – I believe Sir Charles is psychologically aware enough to know that his absence will heat up Egg’s feelings for him; plus, he knows they will meet soon enough because she will be part of Strange’s weekend. And Sir Charles has made sure that Manders will be there, too, which again plays into both genres: Manders is the third wheel in this romance and he is the sap who will take the fall for the real murderer.

Unlike Jane Wilkinson, whose murder plan consisted of switching places with an actor-impersonator and who then spends the rest of the novel essentially playing herself, Sir Charles runs the gamut of dramatic skills, from intense rehearsal, to character roleplay, to brilliant and deadly improvisation. In the end, three people lie dead, two of them unwitting pawns in Sir Charles’ meta-fictional establishment of a traditional closed circle mystery. Reverend Babbington’s murder is a mere dress rehearsal for the real thing so that Sir Charles can practice switching out glasses. And Mrs. de Rushbridger’s death is a ruse designed to convince people that the totally ignorant woman knew something. And there is the potential of a fourth murder: the deliberate framing of Oliver Manders for the murders. It’s cold and ruthless and horrible.

The things one does for love, eh?

When and where?

“The sea – there’s nothing like it – sun and wind and sea – and a simple shanty to come home to.’ And he looked with pleasure at the white building behind him, equipped with three bathrooms, hot and cold water in all the bedrooms, the latest system of central heating, the newest electrical fittings, and a staff of parlor maid, housemaid, chef, and kitchen maid. Sir Charles’s interpretation of simple living was, perhaps, a trifle exaggerated.”

Given that this novel is not one of the travel books, Poirot and company do a lot of traveling: from Loomouth to Monte Carlo, Yorkshire to London. While there is little in the way of description, the plethora of locations adds a brisk pace to the book. You would think that a mystery that begins with “thirteen at dinner” would have more of a Marsh-like pace in the middle, but the suspects aren’t interviewed until Act Three, and then each meeting is brief. That certainly makes the novel move, but it doesn’t help us take all these “suspects” seriously.

Score: 8/10

The Solution and How He Gets There (10 points)

The major weakness of this clever plot is that it isn’t properly clued at all. There is one “legitimate” clue: Poirot receives a letter purportedly from Mrs. de Rushbridger, but that lady could not have known that the detective was on the case.

The rest of Poirot’s deductions suggest that his little green cells are highly magical this time. How could he know that Sir Charles was not in Monte Carlo but in England? How could he do more than guess that the reason the killer had not proposed to Egg was that he was already married? (We see numerous instances where Sir Charles suggests he is too old for Egg; why couldn’t this be the reason for his reticence?) Poirot cannot figure out how Babbington and Babbington alone was poisoned, and while the answer is fascinating – anyone could have been the victim, the point was to practice switching glasses – Poirot comes to the truth immediately after hearing a fortuitous comment from Egg about attending a dress rehearsal.

In Agatha Christie’s Golden Age, John Goddard discusses Christie’s choice of nicotine as a poison. The substance has a terribly bitter taste, and three people have to down it! Babbington doesn’t like cocktails, Strange lost his sense of taste after a recent bout of influenza, and Mrs. de Rushbridger . . . well, she was too startled by the bitterness to spit the candy out. It’s all too convenient, given Christie’s ability to work out plot points like this.

I also have to say that, for a fiendishly intelligent killer, Sir Charles behaves stupidly on several occasions. The first is inviting Hercule Poirot down to Loomouth in the first place. Oh, the ego of actors!! The second is that he kept his nicotine distillery up and running at Crow’s Nest where Miss Milray and Poirot could find it. And the third is that Sir Charles makes a point of questioning Muriel Wills because he suspects her of knowing something about the real identity of Ellis, the butler. His interview with her would suggest that this is correct, and yet he goes right ahead and fills in Poirot on what she said – information that Poirot uses to incriminate Sir Charles in his summation.

Poirot crosses the London crowd who came down to Crow’s Nest off his list of suspects because none of them could have known that Reverend Babbington would be at the party. However, he doesn’t reverse this deduction once he establishes that anyone could have been the victim. I’ll agree that the host of the party seems the most likely suspect here . . . so why doesn’t Poirot or the police or Satterthwaite or anyone suggest looking into the man who issued the invites and fixed the cocktails? No, Sir Charles is given a pass because the plot dictates he must be considered the sleuth of the tale. It’s absolutely clever, and I will repeat it again: it fooled me the first time. But well-clued? Not really.

Score: 6/10

The Poirot Factor

“Like the chien de chasse, I follow the scent, and I get excited, and once on the scent, I cannot be called off it. All that is true. But there is more. It is – how should I put it? – a passion for getting at the truth. In all the world, there is nothing so curious and so interesting and so beautiful as truth . . .”

Considering Poirot here is interesting for the ways his presence and purpose contrast to the novels around him. Coming after Peril at End House, Lord Edgware Dies, and Murder on the Orient Express, where Poirot makes his first appearance literally on Page One and never leaves, the sleuth is remarkably absent for much of this novel. This, of course, works to force Sir Charles upon us as the detective du jour and to set us up for the surprise ending.

Conversely, Three-Act Tragedy is the first of three Poirot novels, published one immediately after the other, where he works as part of a team of investigators who are not police and where the murderer is ultimately revealed to be a member of that team. We have discussed this matter as it pertains to the third of these novels, The A.B.C. Murders, and we will get to the second example later this year. In this particular case, Poirot is drawn into the team rather than its instigator, and seeing him from the sharp vantage of Mr. Satterthwaite, we get an extraordinary amount of insight into the character of Hercule Poirot.

When he learns that Poirot will be attending Sir Charles’ party, Mr. Satterthwaite reveals that they have met before. “Rather a remarkable personage,” he says of the detective. When they meet at the cocktail party, Satterthwaite’s thoughts are more revealing:

“Mr. Satterthwaite suspected (Poirot) of deliberately exaggerating his foreign mannerisms. His small, twinkly eyes seemed to say, ‘You expect me to be the buffoon? To play the comedy for you? Bien – it shall be, as you wish!’”

Throughout the first section, Poirot’s presence is kept to a minimum. In a charming meta-moment, the others joke that Poirot’s presence is a surefire sign that a crime will be committed. (Well . . . isn’t that the truth?) Yet when he is consulted over Babbington’s death, rather than leap to the dramatic conclusion of murder., like Sir Charles, Poirot takes a more cautious approach:

“As a judge of human nature, it seems to me, unlikely in the extreme that anyone could wish to do away with a charming and harmless old gentleman. Still less does the solution of suicide appeal to me. However, the cocktail glass will tell us one way or another.”

When he meets Satterthwaite again in Monte Carlo after Sir Bartholomew Strange’s death, the Poirot we see constitutes a much more realistic portrayal of a retired gentleman than what we were given back in ’26 with Roger Ackroyd. During their conversation, Poirot reveals more about his past than I think we’ve seen since Styles:

“See you, as a boy, I was poor. They were many of us. We had to get on in the world. I entered the Police Force. I worked hard. Slowly, I rose in that Force. I began to make a name for myself. I made a name for myself. I began to acquire an international reputation. At last I was due to retire. There came the war. I was injured. I came, a sad, and weary refugee, to England. A kind lady gave me hospitality. She died – not naturally; no, she was killed.”

This catches us up to Poirot’s first recorded case, and then he describes how that led him to a rewarding second career as a private detective (“I employed my little grey cells.”). Now he really does seem to have retired, and it does not suit him. The scene is played out against their observations of a small child who is bored with leisure and nags his mother for something to do. Mr. Satterthwaite, as perhaps the most erudite companion with whom Poirot ever worked, understands this and appeals to Poirot, both as a criminologist and as a student of human nature, to come along to investigate.

Again, I love the relationship between the two men and wish there had been more of it. Captain Hastings loves Poirot but complains about him incessantly. He finds the sleuth’s vanity an irritant. Here’s Mr. Satterthwaite on the enormous ego of Hercule Poirot:

“Mr. Satterthwaite studied him with interest. He was amused by the naïve conceit, the immense egoism of the little man. But he did not make the easy mistake of considering it near empty boasting. An Englishman is usually modest about what he does well, sometimes pleased with himself over something he does badly; but a Latin has a true appreciation of his own powers. If he is clever, he sees no reason for concealing the fact.”

We learn here that Poirot, like Satterthwaite, is aware that Sir Charles is playing a role:

“Aha! . . . What zeal he has, our Sir Charles. He is determined, then, to play this role, the role of the amateur policeman? Or is there another reason?” The other reason being the burgeoning relationship with Egg, which Poirot has also observed. His acumen at reading these characters explains why Poirot has to enter the case so late; as it is, he has rejoined the group for only a matter of minutes when he begins to conceive of “a very monstrous idea – which I hope and trust cannot be true. No, of course it is not true –“

Of course, Satterthwaite isn’t really Poirot’s “Watson” – he’s Cartwright’s and Egg’s, acting as a combination old wise man and duenna (much to Egg’s annoyance) to the pair. Poirot’s participation is also not Egg’s preference (although, ultimately, she is lucky to have him around.) This is one of four or five 30’s novels where Poirot detects as part of a group but the only one where he has to ask to join in and where he actually apologizes to Sir Charles for not taking his early sleuthing impressions seriously. It’s a fascinating position in which to find the world’s greatest detective.

Score: 10/10

The Wow Factor

Is it a back-handed compliment to name Three Act Tragedy one of the best of Christie’s second-tier mysteries? Is it even true? I do think the novel comes close to greatness in its theatrical playfulness with classic mystery tropes, its mixture of death and romance that remains light-hearted until the very end, and, most especially, the matter of motive. The reason for Babbington’s death is unique within the canon and ties in beautifully with the novel’s theme. The reason for the death of Mrs. de Rushbridger is chilling, and the fact that both sides of the Atlantic got their own motive for Strange’s death is a fun side note.

Three-Act Tragedy has never been thought to break any new ground in the canon. It doesn’t contain the exoticness of the classic foreign-travel mysteries, and while the solution exposes one of Christie’s “unexpected” murderers, it doesn’t have the cachet that places it alongside, say, Roger Ackroyd, Orient Express, or Crooked House, those “special cases” about which people feel so strongly. But I think Christie knew her audience, those movie-going, love-happy folks who relishes a good romantic comedy. She placed one at their feet, and then she pulled the rug right out from under them. It’s a delightful read. I enjoyed its meta-fictional aspects and its humor, best exemplified by the final lines:

- “’My goodness,’ (Mr. Satterthwaite) cried, ‘I’ve only just realized it. That rascal, with his poisoned cocktail! Anyone might have drunk it. It might have been me.’

- “’There is an even more terrible possibility that you have not considered’, said Poirot.

- “’Eh?’

- “’It might have been ME,’ said Hercule Poirot.”

Score: 8/10

FINAL SCORE FOR THREE-ACT TRAGEDY: 42/50

THE POIROT PROJECT RANKINGS SO FAR . . .

- The A.B.C. Murders (46 points)

- Three-Act Tragedy (42 points)

- Cards on the Table (36 points)

- Dead Man’s Folly (28 points)

- The Mystery of the Blue Train (26 points)

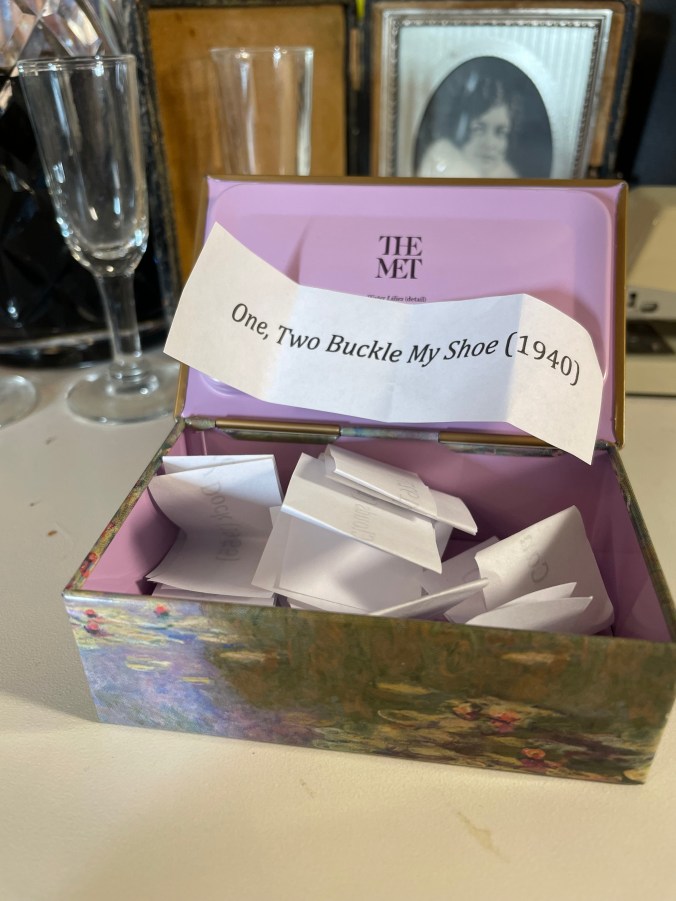

Next time . . .

Is it wise to mix Poirot and politics? Does Christie get extra points for putting her sleuth in the dentist’s chair? Find out next month!

I have had a growing appreciation of this book after re-reading it as well as seeing the Suchet and Ustinov adaptations. Your analysis as usual is spot on.

Still I fell the second murder is just not believable. Even if the dinner guests did not see through the deception of the culprit, there is no way the servants/staff would have been fooled.

LikeLiked by 1 person

But they were. Oh, not enough for the most experienced to not see that Ellis was a most unusual butler, but the fact that nobody recognized the man behind the make-up at close quarters is one of those classic mystery tropes you just have to ride with.

What really fascinated me this time around is the perspective Christie gives us of the murders. The first happens in an instant AND WE ARE THERE, while the other two happen offstage, the last almost as an afterthought. It lightens the tone and thereby lessens suspicion of the killer.

LikeLike

Wouldn’t Ellis have been recognised is a question I asked too. But Christie does say in the book that if Sir C had been outed at his role-playing, he would have simply passed it off as a prank. As he and Dr. Strange were old friends, it wouldn’t have seemed weird.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also, one of the housemaids said, that Ellis spent most of the time by himself in his room.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good point. And since he was a temporary replacement, all the other servants probably thought that was a perfectly proper thing to do. “Don’t get too close.”

LikeLike

Yes, they do say that, and here’s my response: Sir Charles was willing to murder a random person out of a group of friends he’d gathered as a DRESS REHEARSAL for the most technical aspect of his plan to kill Strange. So why not have a similar rehearsal to make sure he could fool all these close friends with a disguise. Why not, say, deliver something or play a waiter at a restaurant or something?

(I’m truly nitpicking here. I like Christie’s plot just fine!)

LikeLike

Playing a waiter—a Christie murderer does do that successfully ten years later in 1944. So perhaps that idea did cross Agatha’s mind too. 😁

LikeLike

Logically, I know that this is – as you say – second tier Christie, but I place this one high in my own personal ranking. To this day I kick myself that I didn’t try and play it when we did our Christie Draft (if only to see what happened). I love Christie mining the theatrical tradition and spirit, the motive for the first murder is one of my favorites in Golden Age fiction, and the deployment of Poirot first on the sidelines before taking center stage is excellent. For what it’s worth, it’s one of the best Suchet adaptations too.

That Sayers quote you cited really resonates with me. A perfect encapsulation of the magic trick that Christie was able to pull time and time again.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I feel like I want to write a big piece on how Christie “presents” her killers. Plenty of culprits are eliminated early on situationally, I.e., the establishment of an alibi. But I love when Christie can manipulate our way of thinking as readers: our understanding of character patterns, our familiarity with character tropes, our tendency to second-guess or wholly misinterpret the significance of things. The famous calendar clue is trotted out incessantly as an example. I love when Christie states a plain fact (“That amiable youth Jimmy Thesiger”) and lets our minds jump to all the wrong conclusions. Here EVERYONE notes that Sir Charles is “playing a role” and canny readers – even the ones who recently read LORD EDGWARE DIES – ignore or excuse that fact because we think he’s Cary Grant!

LikeLike

Great write-up! I didn’t rate this one too highly when I read it – I thought it did get a bit Marsh-y in places. If it seems like nobody had a reason to do it, I can’t weigh up who did or didn’t do it in my head, and the investigators can end up going round in circles. But perhaps you’re right, and reading it as a “romance” instead would set my expectations correctly.

I never noticed that the books with the investigative-team-where-one-investigator-did-it come hot on the heels of each other. Clouds actually has the exact same setup! But Tragedy does it better in terms of the puzzle and the novel elements. The rest do all have different dynamics; here Poirot steps back and the others take the lead; in ABC Poirot is unquestionably the leader of the group; in the whodunnit outlier Cards the partnership is more equal.

As you say, her incredible skill in misdirecting the reader means we don’t notice the same trick being pulled yet again, and it takes a few re-reads to even realise it’s the same trick.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We’ll get to Clouds pretty soon, I imagine. It does a few things very well, but in almost every respect is a paler version of this title.

LikeLike

“One of the best of Christie’s second-tier mysteries” is an apt description. I feel like I can usually remember a mystery’s murder trick, but the cast blur together over time. With Three-Act Tragedy, I can remember the culprit and motive quite clearly 10+ years later, but almost nothing about the murders. It speaks to the strength of the character element here. The ending totally got me!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX (The Blog-iography!) | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #7: Death in the Clouds | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #8: The Big Four | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #9: The Murder of Roger Ackroyd | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #10: Murder in Mesopotamia | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #11: Hickory Dickory Dock | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #12: Elephants Can Remember | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #13: Hallowe’en Party | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #14: Death on the Nile | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #15: Peril at End House | Ah Sweet Mystery!