This month, my Book Club decided to read 1929’s Murder by the Clock, the second mystery novel by Rufus King and the first of eleven books featuring a most unusual policeman, Lieutenant Valcour. At some point, Book Club decided to push the book back to April, but I went ahead and read it anyway since my routine is about to be disrupted by a short road trip. Let me just say that the word “tripping” can’t help but come to mind after reading Murder by the Clock.

If you want to know something about Rufus Frederick King’s life, I have two excellent resources to share with you. Curtis Evans dishes the dirt on King’s fascinating private life, both in his blog The Passing Tramp and in his collection of essays on queer crime fiction, Murder in the Closet. (I’m particularly keen on the way Curtis links Rufus both to fellow Yale classmate (and musical theatre hero), Cole Porter, and to heinous criminal (and classic mystery fan), John Dillinger. You also must check out Mike Grost’s in-depth commentary on the books that sprang from King’s pen.

I offer you these links in case you’re interested in getting up close and intimate with Rufus King – because what you’re going to find here is a review from a reader who just spent the last couple of days flying by the seat of his pants. Of course, I’m grateful to Otto Penzler, whose American Mystery Classics imprint has reacquainted readers with mystery authors great (Queen, Carr, Gardner, Woolrich) and nearly forgotten (Baynard Kendrick, Dolores Hitchens, C. Daly King). In fact, standing ovations to all the small presses who arrange this invaluable service, including Wildside Press, which bought the rights to the Valcour novels over ten years ago and released a lot of them back then.

In her introduction to this new edition, mystery writer Kelli Stanley compares King to his contemporary S. S. Van Dine, but I don’t really see it. Perhaps King’s earlier sleuth, dilettante Reginald De Puyster, had more than a whiff of Philo Vance upon him. But if you want to read a contemporary mystery inspired by Vance, I would suggest Ellery Queen’s The Roman Hat Mystery or 1930’s About the Murder of Geraldine Foster by Anthony Abbot.

What both Queen and Abbot share with King is the concept of the mystery as procedural, as their books follow the investigation into bizarre crimes: Abbot features Police Commissioner Thatcher Colt, while at least the early Queens star Inspector Richard Queen, with assistance from his erudite son. Murder by the Clock introduces us to Lieutenant Valcour, “a mild elderly man with features that were homely but not undistinguished, well dressed in tweed, and not smoking a cigar . . . The faint traice of cultured precision in his speech made (one) suspect foreign origin.”

Valcour is a naturalized citizen from French-Canada, incredibly observant, able to switch from being fatherly to flirtatious, delightfully modern in his attitudes toward race, and abominably wretched in his views on women. I name these last two not as charming traits of a detective but what I suspect were attitudes of his creator.

Clock is every inch the procedural, actually tracking the time it takes for Valcour to investigate and solve the murder (twice over!) of Herbert Endicott, an outright cad, who seems to have suffered a heart attack after surprising an assailant in his bedroom, is pronounced dead, is then pronounced not dead, is revived with a new miracle drug called adrenaline, and then . . . is shot dead under mysterious circumstances right in front of a pair of policemen and another man who was in the act of trying to stab Endicott to death.

If this all sounds sufficiently intriguing to you, then purchase your copy today. I have to tell you, though, that once Valcour has a real corpse on his hands, everything turns loopy in a way that was alternatingly interesting and infuriating.

It’s not that the narrative flags. Divided into thirty-one chapters that take place over a twelve-hour period one night, the book moves pretty swiftly. (The final chapter is a coda that occurs five years later and contains a twist soooo off the rails and poorly explained that it annoyed me to no end), Sometimes the prose creaks a bit, as early twentieth century prose can do, and other times it’s quite lovely. And for a mystery taking place in 1929, King focuses a lot on characterization. Here is Valcour reflecting on the central character of Endicott’s wife:

“A curious, curious woman, with youth and beauty that almost passed belief. He knew her instinctively as one of life’s misfits: complex to a note far beyond the common tune; essentially an Individualist; essentially unhappy from an inevitable loneliness which is the lot of all who are banished within the narrow confines of their own complexity; a type he had seldom met, but of whose existence he was well aware.”

This passage speaks as much to Valcour’s poetically reflective nature as to the type of woman Mrs. Endicott may be. And Valcour pulls this trick on everyone he meets, including his own staff of policemen, every one of whom seems to be from Ireland since they all speak like this: “Sure, and you’ll be wanting the doctor’s report, won’t you, boy-o?” Some of it is fine, and many of the characters we meet are interesting. Occasionally the point of view switches to another character, such as the nurse assigned to guard Endicott after the shot of adrenaline has gotten his heart beating again. Her ruminations on every man she comes across – the doctor, the policemen, the victim! – as potential objects of matrimony is amusing.

And some scenes are quite effective as drama (King did dabble in the world of Hollywood), such as a climactic scene in the Endicott’s attic between Valcour and a character about to attempt suicide. However, all of this is linked together in the strangest of ways. The plot wavers and bumps around, and I found it more difficult to maintain interest in the goings-on than in the trappings.

This might have to do with the character of Valcour, as Stanley describes him in her intro:

“Rather than what would become the standard trope of the stoic, hardworking, step-by-procedural-step police officer, Valcour is an introspective dreamer. Though the novel hops into other voices occasionally, his predominates. He stands apart, alone, and coments on other characters and on his own thoughts in a reverie of near-meta self-awareness and observation. He is as much a Greek Chorus commenting on life as he is a detective.”

That inner commentary interrupts the flow of the narrative but is interesting nonetheless. Maybe it’s the underlying queer sensibility, noted by both Evans and Grost, that one finds in the relationship between Valcour and his younger associates, or in a bizarre scene where the Lieutenant makes one of his only exits from the Endicott home to check on a suspect and finds himself in an interview with a young sociopath named Smith, whose charming Southern persona is both seductive and deadly.

Also in King’s favor is the surprisingly positive consideration of race he imbues in Valcour, moving away from the non-white stereotypes that permeated crime fiction of the early 20th century. Witness the Lieutenant’s thoughts as he examines the scene of the crime:

“For a happy moment he considered the possibility of that curious and sinister Oriental influence that crops up so perennially in the very finest murder cases . . . that elusive figure swathed in gray, white turban above coffee-colored skin, who has a penchant toward religious fanaticism, the esoteric rights of which involve dust . . . Had one, Lieutenant Valcour wanted to know, such an enigma to deal with here? No, he informed himself sternly, one knew damned well one had not.”

But man, oh man, what Valcour and his men think of women! We’re told that all women lie and that, in fact, it’s part of their charm. We learn how women’s reputations are justifiably damaged when they don’t stick by their man – even if that man is a serial philanderer and a rapist. And while I really don’t want to get spoiler-ish, just as Valcour is about to reconsider his extreme chauvinism, King throws in a twist to suggest that women are as bad as men consider them to be.

Do I think I’ll return to the career of Lieutenant Valcour? Well, I’ve had a tattered copy of Murder on the Yacht on my shelves for decades, but Mike Grost says it’s boring. Both he and Curtis are enthusiastic about Murder by Latitude, so one of these days I might give it a shot. I’ll be interested in seeing what my other Book Clubbers think and any thoughts those of you familiar with King would be willing to share.

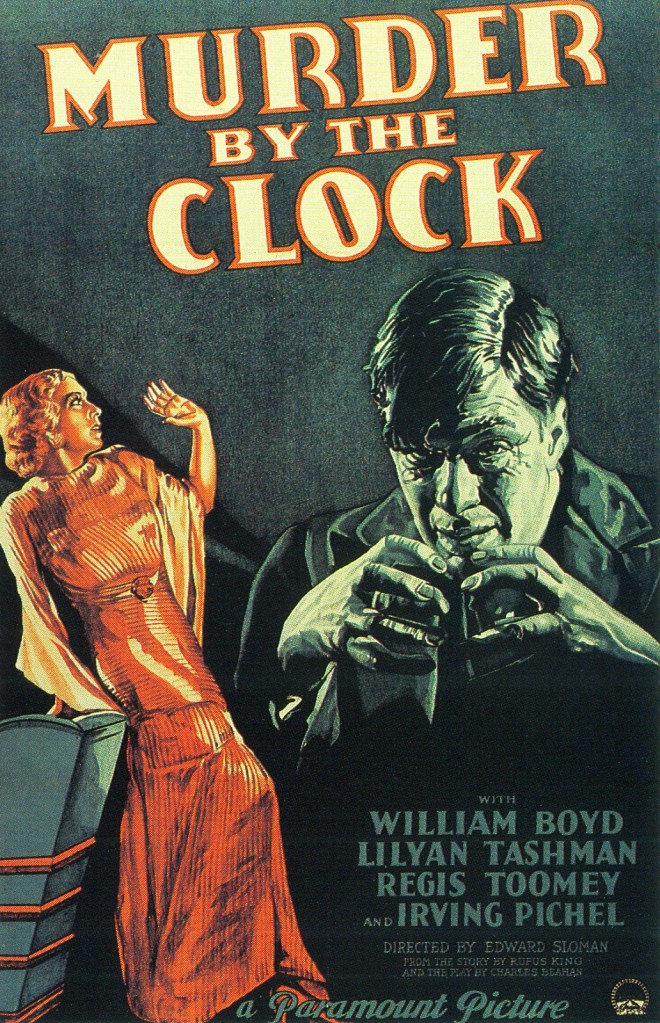

Oh, yes, I mentioned Hollywood earlier: Murder by the Clock was turned into a film in 1931. Oddly, though, the screenplay is an amalgam of the plot from King’s book and a play by Charles Beahan called Dangerously Yours. Some of the characters have the same names as the ones you find between these pages, but the whole mystery skews differently. You can find it on YouTube in a not-very-good print if you’re interested.

I’m only familiar with this novel via the 1931 film version, which, as you know is more gothic horror than whodunit. However, another Lieutenant Valcour novel, The Case of the Constant God, was made into a 1936 film at Universal and is by far one of the best whodunit films of the decade. Unfortunately, it’s very difficult to get to see a copy (I saw it at Cinecon in Los Angeles about 10 years ago). I highly recommend both the book and the novel, though as I say, the latter is very difficult to track down.

LikeLike

I’m only familiar with this novel via the 1931 film version, which, as you know is more gothic horror than whodunit. However, another Lieutenant Valcour novel, The Case of the Constant God, was made into a 1936 film at Universal and is by far one of the best whodunit films of the decade. Unfortunately, it’s very difficult to get to see a copy (I saw it at Cinecon in Los Angeles about 10 years ago). I highly recommend both the book and the novel, though as I say, the latter is very difficult to track down.

LikeLike

I thought I was going to write the intro for this one, I’ve researched a great deal about King’s life, but Otto P., who was throwing me the intros on queer mystery writers, thought on Facebook last year that I said he was homophobic so I got proscribed from writing for Mysterious Press anymore. (I did say the Cornell Woolrich bio he published was homophobic, which I stand by.) It’s too bad the person they asked to do it in lieu made the facile Van Dine comparison. I haven’t read it, but that doesn’t suggest a deep understanding of the period. I’m sorry I was not able to writer for MP on him.

Anyway, thanks for mentioning my blog writing on King, there’s a long piece on Crimereads too. You really should read Murder by Latitude, I think you’d find it fascinating. Murder by the Clock is interesting but as successful in my view, though critics were fascinated with the lead woman character, King often portrayed powerful women with boytoys in tow. He was did drag himself in college and was fascinated by women. And, cliche alert, although a Great War hero and accomplished person, he was dominated by his widowed mother, who refused to listen when he tried to come out to her. So his love turned into loathing, I think. Yet, Woolrich like, he never left her and was narrowly saved from fatal alcoholism after she died.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: “I’ve got (another) little list . . . ” Ten Favorite Mysteries of the 1940’s | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: Murder by the Clock (1929) by Rufus King – crossexaminingcrime