“’Elephants don’t forget,’ said Mrs. Oliver. ‘You know, a story children get brought up on? How someone, an Indian tailor, stuck a needle or something in an elephant’s tusk. No, Not a tusk, his trunk, of course, an elephant’s trunk. And the next time the elephant came past he had a great mouthful of water and he splashed it out all over the tailor, though he hadn’t seen him for several years. He hadn’t forgotten. He remembered. That’s the point, you see. Elephants remember. What I’ve got to do is – I’ve got to get in touch with some elephants..’”

Thirty years before Agatha Christie, at the age of 82, published Elephants Can Remember, the last novel about Hercule Poirot that she would ever write, she produced Five Little Pigs, arguably the best novel about Hercule Poirot that she would ever write. Both books rest on the same premise: a young girl’s marital happiness rests on the uncovering of the truth about her parents’ long-ago deaths. Poirot himself acknowledges the parallels when he reminisces with Superintendent Spence over the many murders in retrospect he had investigated. The enthusiasm both men share over these past cases, two of which (Mrs. McGinty’s Dead, Hallowe’en Party) they worked on together, is so infectious that I wouldn’t have minded reading a hundred pages of such remembrances.

Unfortunately, Elephants is – what, replete? burdened? Saddled? with page after page after page of vague remembrances that are so unhelpful –they have to be if this in order to stretch this out to novel length – that our chief pleasures reside in outlying descriptive passages and side conversations, like the one between Poirot and Spence. There is a puzzle, of sorts, that I imagine most of you will solve well before the solution is revealed – just like I did at the age of 17 – because of Christie’s use of a trope decried by both Knox and Van Dine. That solution reveals the spark of a tragic novel that might have been, had it not been for the two hundred pages of elephantine mis-remembering that came before, along with a great deal of charming but unnecessary filler. Ultimately, the facts don’t add up – where on earth were the editors?? – but the final reckoning does touch the heart.

John Curran informs us that the scant twenty pages of notes, scattered over four notebooks, contain much confusion and many irrelevancies and concludes that the book is “a disappointing swan song for Poirot.” Mark Aldridge sums it up well, calling the book “probably Christie’s least exciting mystery novel, as it stretches a good idea for a short story beyond breaking point . . .” I myself appreciate the solid amount of time we get to spend in the presence of Ariadne Oliver, who has never been given so much to do (and has never before seemed so clearly a stand-in for her creator), but . . . oh, how I wish dear Mrs. Oliver had been given a better case to investigate.

Well, my friends, we had better proceed – before I forget . . .

* * * * *

The Hook

“’You see, it is a matter of the greatest moment to me. Something that I really feel I must find out. Celia, you see, is going to marry – or thinks she is going to marry – my son, Desmond . . .’ Mrs. Burton-Cox leaned forward and breathed hard. ‘I want you to tell me, because I’m sure you must know or perhaps have a very good idea how it all came about. Did her mother kill her father or was it the father who killed the mother?’”

Mrs. Oliver meets the odious Mrs. Burton-Cox at a literary luncheon, the kind both she and fellow mystery author Agatha Christie detested. By the time they start talking, ten pages in, we have been treated to dissertations on the wearing of hats, hairstyles, false teeth, and the general unpleasantness of a luncheon for a shy author. (At least the food was delicious!) Finally, Mrs. B-C says hello, lays out the premise of the book, and Mrs. Oliver is off and running.

At first, she wants to run in the opposite direction; the questions, after all, were impudent and none of the woman’s business. She also might want to ask herself (as I asked myself) how on earth the woman knew Mrs. Oliver was Celia Ravenscroft’s godmother! It isn’t the sort of fact you would find in an author’s CV. Still, as Mrs. Oliver says, “I’m afraid really I’m just a nosey-parker, “and so she consults Hercule Poirot and, over coffee and cordials, they decide to pursue the answer. As much as I love seeing Poirot and Mrs. Oliver together again, things start to go off the rails pretty quickly.

Most of the trouble revolves around dates and ages. One has to assume that Christie’s own mindset was responsible for this, but it feels illogical for Poirot to follow such a garbled path to the truth. It would have been so easy to pin down facts from newspaper articles and police reports – although Poirot does consult the police and even they are vague about time – and further information could have been gathered with more reliable resources, like the mysterious Mr. Goby. Heck, there’s a graveside Poirot visits where the dates everyone died are literally etched in stone. And yet, he waits and waits to visit that graveside. And he doesn’t call in Mr. Goby until Chapter 16! It’s as if Poirot and Mrs. Oliver want to base their investigation not on facts, but on the fragile memories of elephants.

And make no mistake: our sleuths are a pair of old elephants as well. Mrs. Oliver is vague on the details about her long friendship with Molly Preston-Grey. They both quickly forget Mrs. Burton-Cox’s name. And neither can quite remember how long they themselves have been friends. (I’ll tell you: it was in 1936 that you solved the murder of Mr. Shaitana together, so . . . thirty-six years and change!)

I fear we’re in for a bumpy ride!

Score: 5/10

The Closed Circle: Who, What, When, Where, Why?

Who?

“Mrs. Burton-Cox dipped a lump of sugar in her coffee and crunched it in a rather carnivorous way, as though it was a bone. Ivory teeth, perhaps, thought Mrs. Oliver vaguely. Ivory? Dogs had ivory, walruses had ivory and elephants had ivory, of course. Great big tusks of ivory.”

In a way, it’s a shame that Poirot mentions Five Little Pigs here because in every way, Elephants suffers in comparison. This is especially true with the characters. In Pigs, the client, Carla Lemarchant, the five titular suspects, and even the various attorneys and others who provide testimony all leap from the page. The “elephants” all make for interesting cameos, although their “testimony,” which contradicts and doubles back and forth, is infuriating. The all-important trio of Molly, Dolly, and Alistair should be the shining beacon here, since Christie was a master at creating romantic triangles.

Unfortunately, due to both the vagaries of the elephant’s recollections, coupled with the necessity for Christie to be vague so as not to spill the beans immediately, it’s hard to pin down who these people are until Poirot reveals the tragic truth at the end. Their descriptions are all over the place. As author/biographer Robert Barnard notes: “At one time we are told that General Ravenscroft and his wife (the dead pair) were respectively sixty and thirty-five; later we are told he had fallen in love with his wife’s twin sister ‘as a young man’.” And if we figure Molly’s proximity to Mrs. Oliver in age, both of these suppositions must be wrong as Mrs. Oliver is somewhere between 70 and 85.

Christie does much better with the present-day characters of Mrs. Burton-Cox and Celia Ravenscroft. The former is a magnificent gorgon who is unmasked at the end as the true villain of the book. And Celia strikes me, much like Carla Lemarchant, as a realistic depiction of a young woman under these circumstances, the kind of character Christie did really well throughout her career. Desmond Burton-Cox is an earnest young man who proves worthy of Celia’s love and our sympathies.

Once again, I must recommend that if you want to tackle this book you listen to Hugh Fraser reading it. He creates distinctive voices for a dozen old women, and his Mr. Goby – nasal and pedantic – is a delight!

What?

As my friend Kemper Donovan will tell you, the plot of a mystery is essentially double-layered in that it consists of the world as it appears to be and the world the way it truly is. A good readable mystery will entertain you with the first layer while subtly weaving clues to point you in the direction of the second layer, all the while obfuscating that truth by interweaving intriguing red herring subplots into the mix.

Elephants suffers because 1) the world as it appears to be is garbled beyond belief, and 2) no red herring subplots are introduced into the narrative. Poirot starts with Mrs. Burton-Cox’s question: did General Ravenscroft murder his wife and then commit suicide, or was it Molly Ravenscroft who wielded the gun, shot her husband and then herself? Acting on the premise (which turns out to be wrong) that nobody is alive who knows the answer to that question, Poirot and Mrs. Oliver must turn to the “elephants” from the past to determine a possible motive on the husband and/or wife’s part.

They come up with vague stories of a children’s tutor who Molly fancied (never proven, and the tutor is never sought out to be questioned) and of a young woman who took dictation for the General as he wrote his memoirs and with whom he might have dallied (if this was Zelie, then that theory was simply a story). A single vague reference to the gardener being an angry man goes nowhere. A lot of the elephants give contradictory descriptions of Molly’s personality, which clearly means they’re mixing her up with her twin sister, Dolly. But this makes no sense whatsoever, because as much as Molly loved her sister, they spent very little time together and it makes no sense that friends would mix up their very different temperaments.

While we wait and wait and wait for the true facts to come out, I found myself entertained by the present-day story of Mrs. Burton-Cox and her attempts to separate her son from his girlfriend. The interfering mother is a tried-and-true villain, from classic literature to soap operas. (Two of the most entertaining characters on The Gilded Age are I.M.s, and they have both just gotten their come-uppance in delicious fashion!) It turns out that Mrs. B-C is more of a monster than we thought, and the unwrapping of this information helps us pass the time until someone can hand Poirot specificinformation about the principal characters.

One may ask why everyone in Five Little Pigs could remember what had gone down sixteen years earlier just fine, but they can’t get their facts straight about the Ravencrofts. It turns out that Mrs. Oliver may be interviewing the wrong elephants! It’s interesting (I use that word ironically!) that the first few old women are garrulous but unhelpful, but the last few characters are clear as a bell. Otherwise, the story may have never ended.

When and where?

I have already alluded to this matter several times, but this is the most infuriating aspect of the book. When did this couple die? Wasn’t it in the paper? How old is Celia? She can’t or won’t pin her age down. It’s impossible to nail down details of time and place because by letting us see everything through the rheumy eyes of extremely forgetful people, most of whom shouldn’t be nearly as old as they are, testimonies are awash with contradiction. In the end, it’s better to not even try; just let the story and the better details wash over you.

Score: 2/10

The Solution and How He Gets There (10 points)

“We are standing here where two lovers once lived. Where two lovers died, and I don’t blame him for what he did. It may have been wrong, I suppose it was wrong, but I can’t blame him. I think it was a brave act, even if it was a wrong one.”

The final chapter “Court of Inquiry” lays out the solution, which should be obvious to any reader with some experience of the genre. But it is a tragic story, and it hints at what might have been a lovely Westmacott-type novel, had not the insistence been made on or by Christie to craft another puzzle book. I solved this case as soon as I spotted the word “twin.” It was clear to me that Dolly had killed Molly and that Alistair had shot Dolly as one would put down a rabid pet and then shot himself because he could not live without his wife. (This strikes me as a very English thing, in that the children were simply sent away to school with no thought as to how they might take the deaths of their parents.)

In my vague memories of an earlier read, I thought Dolly was trying to replace Molly as Alistair’s wife. They had, in fact, been lovers until Alistair sensed something wrong about Dolly’s mental state (shades of Lord Easterfield and Miss Waynflete!) and turned his attentions to her conveniently beautiful twin sister. (Dolly then went on to marry someone else and become a child murderer, like another Christie madwoman, Mrs. Lancaster from By the Pricking of My Thumbs.) It’s a relief to know that no replacement was involved: Alistair simply let Dolly live Molly’s life for a few weeks as he made arrangements for the children and set up his execution-suicide.

Of course, Zelie, who loved Alistair, was in on the whole thing, and if Poirot or Mrs. Oliver had only gotten to her sooner, this whole novel would have been unnecessary. But there were a few clues that led Poirot to the truth. The most obvious was that the family dog turned against his beloved mistress in the final weeks. (Dogs know their masters!) Then there’s the matter of the wigs – if the word “elephants” is found in the text four hundred times, then the word “wig” is used nearly as frequently. Molly had four wigs. For some reason, that seemed a crazy amount to everyone. Christie had to save the fact till the very end that Molly had TWO wigs – a reasonable amount – but that “Molly” had ordered two more right after her sister’s death.

Add to this that the housekeeper was nearly blind. Put it all together and it spells . . . something. How lucky that Zelie was able to give the whole story – as an eyewitness, yet! – so that Poirot’s mad suppositions could be proven correct. I can’t help thinking that if you removed Poirot and the clues and made this a story about Celia trying to find the truth in order to save her impending marriage that this might have been a better story.

Score: 5/10

The Poirot Factor

Once again, we have the pleasure of Poirot’s company from start to finish. This time, he shares the stage evenly with Mrs. Oliver, and it feels more like a partnership than ever before. That is the best thing about this book. But, as I’ve gone over before, as much as their approach to this case may have involved a lot of luck, I still believe that there was a more logical way to gather information and that their reliance on elephants was a caprice to serve the needs of their Creator – Agatha Christie.

Score: 8/10

The Wow Factor

Whether or not there is enough meat on its bones to craft a puzzle plot, the central idea that Christie came up with, at eighty-two years of age, is emotionally evocative. And though the novel is stuffed with woolly-headed “elephants” half remembering past tragedies, Christie still managed to give us a great villain in Mrs. Burton-Cox and provide some lovely scenes between Poirot and Mrs. Oliver.

It’s interesting to watch the adaptation that premiered during the final season of Poirot. Most of the novel is contained there, and it is quite moving. However, the writers saw that they didn’t have a real mystery: as soon as mention is made that Margaret and Dorothea were twins, everything clicks into place. And so, the adaptation drops in a modern-day murder and a wholly original killer – someone who is briefly mentioned in the novel but never makes an appearance – and that scenario is rather skillfully interwoven into the original plot. And while it’s not a particularly original or mystifying plot line, it does employ a couple of ideas that we have seen in other Christies – the question of who is alibiing who, and the theme of a child avenging a wronged parent (although the idea that this parent was “wronged” is laughable). Greta Scacchi makes a great Mrs. Burton-Cox, and Zoe Wanamaker really shines as Ariadne Oliver here.

None of this gives the novel itself much of a “Wow” factor, but I thought it was worth a couple of points.

Score: 2/10

FINAL SCORE FOR ELEPHANTS CAN REMEMBER: 22/50

THE POIROT PROJECT RANKINGS SO FAR . . .

- The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (48 points)

- The A.B.C. Murders (46 points)

- Three-Act Tragedy (42 points)

- Cards on the Table (36 points)

- Death in the Clouds (35 points)

- One, Two, Buckle My Shoe (34 points)

- Murder in Mesopotamia (30 points)

- Hickory Dickory Dock (29 points)

- Dead Man’s Folly (28 points)

- The Mystery of the Blue Train (26 points)

- Elephants Can Remember (22 points)

- The Big Four (21 points)

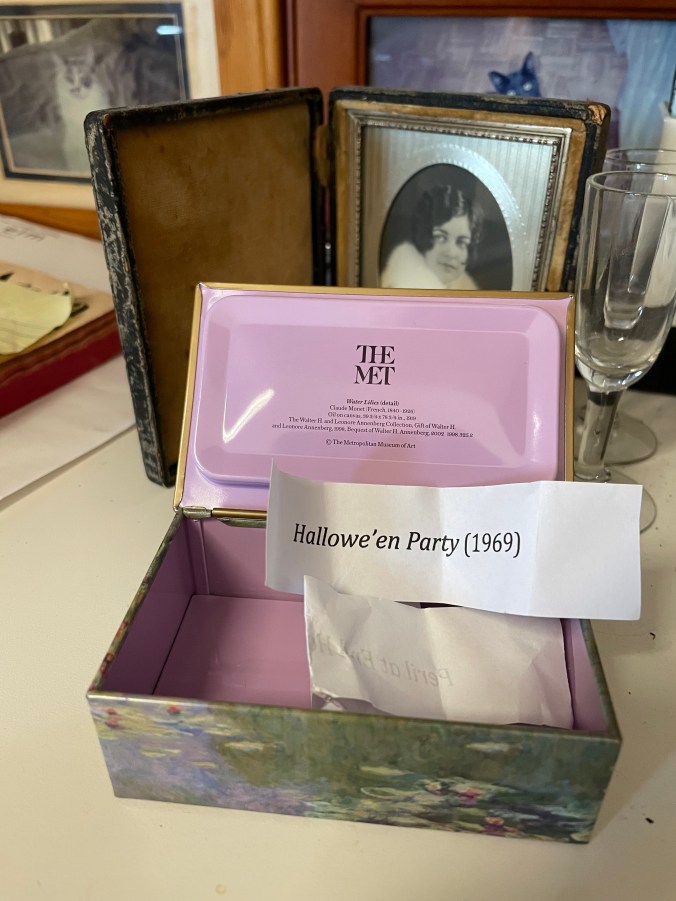

Next time . . .

By the luck (?) of the draw, we have the perfect title for Hallowe’en. (I just wish it was a better book!)

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX | Ah Sweet Mystery!

So sad that this in the last Poirot. I suppose no-one had the courage to tell her that it was time to stop. Best really to think of Curtain as his swan song. I agree too about Hugh Fraser – he’s wonderful!

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

I keep asking myself: was Christie editor-proof? Did her publishers feel it wasn’t worth the bother, that her name would make them millions no matter what the product she put out? I think this could have been a much better book if only an editor had pored over it with her!

LikeLike

Perhaps they couldn’t even broach it with her. She was so famous by then.

>

LikeLike

It’s all very sad, equally so in the case of POSTERN. Brad will know more – my understanding is that Christie had been increasingly intransigent when it came to the editing of the manuscripts after her dictations were transcribed

LikeLike

Something has gone wrong with your scoring system, Brad. There’s no way Elephants is better than Big 4! This would have made a really good short story and I do like the flip from “same woman, different hat” to “same hat, different woman” and the dog’s behaviour – which is logical unlike that which we saw in book group’s Keeper of the Keys.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Story-wise, they’re both problematic in their own peculiar ways. And TB4 is admittedly more fun to read. What makes this one slip just ahead of can be summed up in two words, John: Ariadne Oliver. And, frankly, I think Mrs. Burton-Cox makes a better villain than Numbers One, Two, Three or Four!

LikeLike

This is still one that I need to re-read at some point. Just need to brace myself lol It might have been nice if the final solution had been a false solution in the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, and that all three of those obnoxious people had been murdered by the dog!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was a sad swan song for Agatha and for Poirot.

Where was the editor?!?!?!?!

The movie really improved on the novel, taking those bare bones and spinning them into something gothic.

The Thai film “Twin” or “Alone” is VERY loosely based on this novel and it is a winner.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #13: Hallowe’en Party | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #14: Death on the Nile | Ah Sweet Mystery!

Pingback: THE POIROT PROJECT #15: Peril at End House | Ah Sweet Mystery!