Let me set the stage for you . . .

Everyone who loves Agatha Christie has discovered her in their own unique way. Ask someone “What was the first Christie you read?”, and there are sixty-six possible answers – and that’s if you’re only counting her mystery novels. Each of us has our origin story, whether it was a cast-off paperback found in a summer cabin or a gift from a mystery-loving aunt, or even a cozy evening curled up with Mum watching David Suchet. For as Mark Aldridge reveals at the very start of Agatha Christie on Screen, some of her most adoring fans have never read a page of Christie in their lives.

My story is a little different: I was nine years old, and had a favorite babysitter named Steve who loved to regale us with detailed retellings of books or movies he loved. These stories could last for hours and often took place over several sessions. The one that stuck with me the most concerned ten strangers trapped on an island with a homicidal maniac. As they get bumped off, one by one, in horrible ways, they begin to realize that the killer was not hidden on the island but a member of their own party!!!

Sixty-one years later I keenly remember that experience. It was a tale that lent itself to theatrics! The first victim tossing back a cocktail and clutching his throat in agony! The search for a butler that ended in the basement with the discovery of his body hacked to pieces! (Okay, maybe Steve exaggerated the violence a bit for our benefit.) The moment Vera enters her darkened bedroom and feels the touch of a clammy hand! Amateur actor that he was, Steve told it so well, but when I discovered the actual book in a store a year later and begged my mom to buy it for me, Christie’s own words cast the same spell over me.

Just as our origin stories are different, so are our reasons for loving her. Obviously, we adore her facility with puzzles – although there are those who prefer her thrillers! And we are crazy for Hercule Poirot, right? Except some of us are devout Marple fans! We re-read her over and over for the nostalgia factor, or because her canon constitutes a social history of middle-class England from the final days of World War I through the Swinging Sixties. We love her dialogue, which lends itself so well to adaptation. We love the cleverness of Death on the Nile, the comedy of Mrs. McGinty’s Dead, the darkness of And Then There Were None, the human drama of Five Little Pigs.

And there are qualities about Christie that may achieve personal importance depending on the things that matter to us in our own lives. I have devoted my professional career to the theatre. As a child, I entertained notions of being a movie star. But life contains as many twists as an Agatha Christie mystery, and in the end, I became not an actor but a director, as well as a teacher of theatre arts and film studies. Through the years, I incorporated my love of Agatha Christie in any way I could. I taught my drama students the elements of a classic whodunit – the closed circle of suspects, the isolated setting, the layering of clues – and then I made them write and perform their own mystery plays. I also had the good fortune to direct a half dozen productions of plays adapted from Christie’s stories. And while our discussion ahead is not about her work in the theatre, it is with her plays that I’d like to begin.

* * * * *

Agatha Christie’s first novel was published in 1920. Her first play appeared ten years later. Black Coffee was written as a response to Christie’s dissatisfaction with how other playwrights adapted her work. Many are aware of her diffidence regarding how Hercule Poirot was portrayed onstage; Black Coffee would be the only play she wrote that included her famous sleuth. But Agatha was more concerned with the awkward attempts by other writers to transfer the plots of her books to the stage. She writes in her Autobiography:

“A detective story is particularly unlike a play, and so is far more difficult to adapt than an ordinary book. It has such an intricate plot, and usually so many characters and false clues, that the thing is bound to become confusing and overladen. What was wanted was simplification.”

And simplify she did, excising characters and clues at will, honing the focus of the action on the emotional effects of murder on a small circle of people. Nowhere is that more clearly seen than in Murder on the Nile, one of six productions of Christie’s plays that I had the good fortune to direct. The cast of characters from the book is cut in half, and nearly every red herring is eliminated. What we end up with is a human drama that can be emotionally gripping, but it is hard to keep audiences mystified by a puzzle with no suspects. The play was not a commercial success.

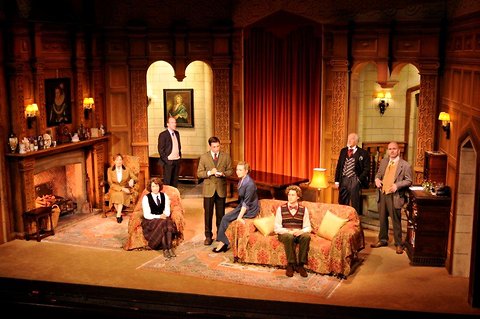

On the other hand, The Mousetrap is the longest-running play in human history, and it manages this with hardly a clue in sight. Christie makes brilliant use of the tropes of classic detective fiction – a secluded setting full of atmosphere, a group of strangers cut off from the rest of the world, a serial killer loose amongst them – all concluding with one of her signature surprise endings. I’ve directed it twice, and I consider it “a well-made play” but not a particularly extraordinary one. What makes it work is not necessarily the characters or the surprise ending; it’s the way Christie puts everything together. The Mousetrap is a success because of its inherent theatricality: the series of introductions to each character, culminating with a dramatic entrance on skis of the policeman; the moment when a radio announcer gives a description of a murderer’s costume, just as the heroine is hanging up her husband’s cast-off clothes . . . and, item by item, they match! There’s the murder of Mrs. Boyle that ends Act I, performed before our eyes. And there’s the final confrontation between the killer and their final victim-to-be, which starts off oh so quietly and builds into a scream.

The Mousetrap is one of a triumvirate of plays considered to be Christie’s best. The other two are And Then There Were None and Witness for the Prosecution. To my mind, Witness constitutes a potentially brilliant evening of theatre. Some of the elements of the play can be found in the short story upon which it is based, including one of the most theatrical elements – a bit of disguise. But Christie knew how inherently dramatic a courtroom drama could be: she had, in fact, tried to end her first novel in a courtroom before being shot down by her publishers. Witness is awash with drama from the start, and its boldly melodramatic finish is a distinct improvement on the intellectual twist of the story’s ending.

I’m less enthusiastic about Christie’s adaptation of And Then There Were None, no doubt because it is my favorite novel. The plot from the book is more or less there, but Christie was convinced that 1943 audiences would complain about the novel’s dark ending and came up with a happy romantic finish that subverts the powerful nihilism of the book. The same could be said about the insertion of comedy, particularly in the reworking of William Blore. Maybe this all worked “theatrically” at the time, and the play garnered good reviews and had a long run. When I directed it, however, I couldn’t stop fiddling with it: I managed not only to insert the original fates of every character into the script but to add dialogue from the novel that I felt was inherently more theatrical than scenes written for the play.

* * * * *

I tell you all this because I’m about to tackle a question that was posed to me by my friend, Teresa Peschel, the author of, among other works, two books about the film adaptations of Christie’s work. When we met, at the 2024 Agatha Christie Festival, we bonded over our love of these films. A year after this, Teresa reached out to me with an idea that she thought, given my love for Christie and for the theatre, would be more up my alley than hers. The question she posed was: “How did Agatha’s extensive experience in the theatre affect her novel writing?”

Initially, I’ll admit that I was tripped up by the question. By “extensive experience in the theatre,” I assumed Teresa was referring to her forty-plus-year long career writing for the stage. Yet here’s the thing: Christie’s first play was produced in 1930, after she had written nine novels, and the next play wouldn’t appear for another thirteen years, coinciding with her 33rd mystery novel – the halfway point of her writing output! Meanwhile, we can find strong evidence of Christie’s sense of theatricality with her very first novel!

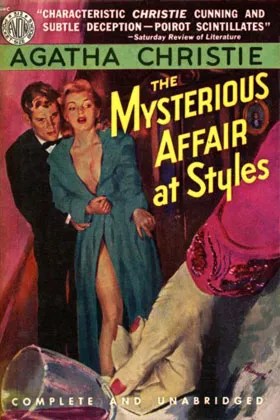

1920’s The Mysterious Affair at Styles is loaded with theatrical elements! The scene of the crime, Mrs. Inglethorpe’s bedroom, feels throughout like a stage set. The entrances and exits of characters are carefully delineated, there is heightened drama in Emily’s manner of death and the family’s reaction to it, and the room is chock full of important props that are strewn all about the place. Hercule Poirot is given a powerful entrance as befitting the introduction of what will become one of the most famous and beloved detectives of all time. In one of the most descriptive passages in the canon, Christie presents a character who, her own opinion notwithstanding, was born to appear on the stage and screen.

“Poirot was an extraordinary looking little man. He was hardly more than five feet, four inches, but carried himself with great dignity. His head was exactly the shape of an egg, and he always perched it a little on one side. His mustache was very stiff and military. The neatness of his attire was almost incredible. I believe a speck of dust would have caused him more pain than a bullet wound. Yet this quaint dandified little man who, I was sorry to see, now limped badly, had been in his time one of the most celebrated members of the Belgian police. As a detective, his flare had been extraordinary, and he had achieved triumphs by unraveling some of the most baffling cases of the day.”

Despite the limp (which would shortly disappear), Poirot moves with more agility here than he ever will again, scampering throughout rooms and landscapes in search of clues. The moustache will change as well – and speaking of facial hair, a final theatrical touch is the employment of disguise – a false beard – in order to give the murderer an alibi. Clearly, Christie began imbuing her stories with theatrical elements and flourishes long before she experienced success on the London stage.

So . . . how to tackle this question. The first thing I did was to pull down a copy of Aristotle’s Poetics from my shelf. In it, the famed Greek philosopher identifies six crucial elements of theatre: plot, character, thought, diction, music and spectacle. I began to brainstorm, just as Christie might have done when coming up with the skeleton of a new novel. (I should have used a notebook because my list of ideas started to stretch the size of my Word document to an unwieldy size!)

My first thoughts looked like this:

- 1. Plot – the “soul” of the tragedy, perhaps the most important element in Christie

- Theatrical moments within a plot

- Entrances and exits

- Order of Scenes

- 2. Character – or community, or closed circle of characters

- Actors as characters

- Characters who play a role within the “reality” of the story

- 3. Thought (Theme) – the why, the motive

- Orient Express (tragedy)

- And Then There Were None (horror)

- After the Funeral (comedy)

- 4. Diction (Language)

- the dialogue – the rhythm of speech?

- the distribution of clues within dialogue

- 4. Music (Song)

- the utilization of actual song

- nursery rhymes?

- 5. Spectacle (Visual Elements)

- The creation of theatricality within a setting (crime scenes; country houses; planes, boats & trains)

- Costume/characters in disguise

- Other visual trickery

I thought that if I began with the early influences of theatre on Agatha and then simply followed this outline, I might just have my . . . my book? My series of posts? My future presentation? Let’s just call it my whatever it is that this turns out to be. Today is the fiftieth anniversary of Agatha Christie’s death, and she is as popular as ever. If I feel at all reticent about whether sharing these thoughts is a worthwhile enterprise, I take comfort in the message Teresa recently shared with me. She and her husband Bill have undertaken a project around the work of Jane Austen (another favorite author of mine). Jane wrote six novels that were published over the course of six years – two of them posthumously because she died at 42. Agatha’s career spanned fifty-six years and encompassed sixty-six novels, dozens of short stories, and a parallel career in the theatre, before she died at the age of eighty-five. And yet Teresa points out that a bibliography of books about Jane Austen would run to hundreds of pages of small print, whereas the one the Peschel’s included in their book on Christie’s film numbers only a dozen pages.

Teresa’s message concludes: “Think how much more Agatha wrote than Jane and how much more she did in her much longer life . . . As Agatha recedes into the past and out of living memory, there will be more and more and more to write about to explain her world. Your book, Brad, will be the first of many.”

Okay, Brad, let’s begin next time at the beginning, with Christie’s childhood introduction to the world of the theatre. Break a leg!

I very look forward to seeing where this project goes!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am THRILLED with your new, exciting project! I knew you could do it. This will be a marvelous book, a worthy addition to the bibliography about Agatha, and ground-breaking scholarship in its own right.

Is that high praise? Yes! Is it likely? Yes! According to my newest issue of JASNA news (we recently joined), a big new book about Jane Austen is about the writers that she read. Who has written about the authors who influenced Agatha?

Anyway, Agatha has had a theatrical mind since her earliest writing days. In “International Agatha Christie, She Watched,” we include a chronological listing of Agatha’s writing starting on page 298. According to the Agatha Christie wiki — I’d vote that Dr. John Curran discovered this fact and if he didn’t, it was Julius Green — she wrote her first play, “The Conqueror” in about 1909. To my knowledge, “The Conqueror” has never been published. Agatha was 19.

Sometime between 1910 – 1920, she wrote the play “Teddy Bear.”

In 1914 (about), she wrote the play “Eugenia and Eugenics.”

Between 1915 – 1920, she wrote the play “The Clutching Hand.”

In the 1920’s (no year is known), she wrote three more plays: “Ten Years”, “Marmalade Moon,” and “The Lie.”

in 1921, when she was 31, she wrote the play “The Last Seance” and after that, you know how much she wrote.

Until I worked out her chronology of writing, I had NO IDEA how much she’d written from the very beginning! I didn’t know how many plays she’d written. Or poems!

I’m really looking forward to seeing what you discover about Agatha Christie and the theater’s influence on her novels and short stories. This will be fun and I don’t have to do any work.

LikeLike

Do you know what Best Babysitter Steve went on to do? I have always been curious: he pops up more frequently than Tommy and Tuppence.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I realized that, too, and so a couple of years ago, I tried to track him down. I really did! I think I had heard a rumor that he became a judge, and I looked all over the place and finally found a judge with his name up north. I went so far as to leave a message on an office phone. Either I got the wrong person, or he was way too embarrassed to respond to me! Anyway, sometimes you’re heroes just get bigger because you never find out what happened to them!

LikeLike

A judge? After enthralling you with a story about ten people lured to an island where they are picked off one after the other by a twisted evil genius – but who could it be?

Delicious if true.

LikeLike