Two hundred posts are something to celebrate. It’s time to talk about the book that changed my life.

The fact that Agatha Christie is my favorite author has as much to do with her place in my own history as her position as one of the greatest mystery writers of all time. She did not convince me to become a mystery fan; Encyclopedia Brown, the Hardy Boys and Perry Mason (on TV) had already accomplished that. Also, having the coolest babysitter in the world helped. Steve Levy loved monster movies and mysteries, and his experiences translated into serialized bedtime stories for my brother and me that, under Steve’s tender care, were guaranteed to inspire nightmares. Who else gets put to sleep with the story of Norman Bates, told in ten easy installments? (Steve taught me both the meaning and the efficacy of cliffhangers.) My favorite “Levy-bian” Nights tale was the one Steve related about ten strangers trapped on an island who get bumped off one by one. In his version, the deaths were a whole lot gorier than they turned out to be in the book! Needless to say, when I uncovered the paperback version of Ten Little Indians (a tie-in to the mediocre second film adaptation that came out in 1965 starring Shirley Eaton and Hugh O’Brian) a couple of years later, I begged my mom to buy it for me.

And that could have been that! A few years later I would see Psycho for the first time, and soon after that I would read “The Most Dangerous Game” and this creepy little story from an Alfred Hitchcock collection about a guy who turns into a giant fungus. I could have checked them all off as “Stories My Babysitter Told Me” and been done. Instead, I went back to the paperback rack at the drugstore in Daly City and discovered that the author of Ten Little Indians had written loads of other books. So I bought another one. And out of all the books in all the world, I chose Murder on the Orient Express.

This is me – pretending to be a normal little boy!

This is me – pretending to be a normal little boy!

The rest, as they say, is history. And it’s my history, one of the first really important choices I made. I cannot begin to explain how reading Christie – followed by Queen, and then Carr, and then Marsh and Brand and Box and Stout and on and on – how reading them all got me through the agonies of adolescence. We who banter on about GAD fiction know what mysteries did for a large segment of the human race between World War I and World War II. I was going through my own mental and emotional conflagrations, and Christie “reestablished the social order” in my head and heart.

So let’s embark on a journey aboard the Orient Express, both as a novel and in its four distinct film versions, including the latest by Kenneth “What’s With the ‘Stache, Dude?” Branagh, which I saw this very day! In order to truly have my say, I cannot avoid spoilers, so you had best be familiar with this novel before you hand me your boarding pass.

THE NOVEL

The Set-up

Really? Somebody remained behind who has not read this book?? Ohhhh, very well! Here’s a quick set-up:

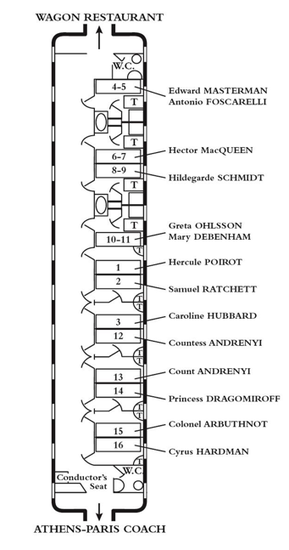

Winter 1934 finds Hercule Poirot in Syria, saving the honor of the French Army. His plans to play the tourist for a few days of relaxation are dashed when he gets an urgent telegram to return to a case in London. He tries to book passage on the famed Simplon-Orient Express, but – oddly for the season – the train is full. Fortunately, Poirot runs into his friend and fellow Belgian, M. Bouc, a director of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons Lits, who wangles Poirot a first-class compartment on the Stamboul-Calais coach. An unwelcome snowstorm strands the train in the Balkans, converting the luxurious transport into an isolated country mansion where a particularly violent (for Christie) murder makes suspects out of an international assortment of strangers.

Christie at Work

If there is a theme at play here – and there is, folks! – it’s Justice. I think we all know that Christie embraced the legal system and the idea of capital punishment with great fervor. In 4:50 From Paddington, after Miss Marple has captured a killer, she expresses with little old lady-like vehemence her disgust that a change in law will rob the community of a good hanging. In 1934, Poirot is at the height of his fame and powers, as evidenced by the international clamor for his services to assist in uncovering criminals and dispense justice. In Orient Express, that need for Poirot figuratively spills over from fiction into real life, for in this tale, Christie applies the Belgian’s skillset to a thinly disguised true crime.

In 1932, America was gripped by the kidnapping of Charles Lindburgh’s son. The baby was taken on March 1, ransom was paid, and then, tragically, his body was discovered in May, buried in the woods. A family maid was suspected of involvement in the crime, and when her protestations of innocence were not believed, she committed suicide. Eventually, the kidnapper, Richard Hauptmann, was captured, convicted and sentenced to death. Seeking privacy after the tragedy, the Lindburgh family fled to Europe and remained there until 1939.

Christie must have started writing during, or immediately after, the trial. She borrowed liberally from the Lindburgh case, including the tragedy of the innocent maid. The novel was published on 1 January, 1934. (Hauptmann would not be electrocuted till 1936.) We’re talking about a novel that was literally “ripped from the headlines” here. I can only imagine the aura of sensationalism that must have surrounded its release.

MotOE certainly seems to have all the trappings of a traditional GAD mystery: an isolated setting, a closed circle of suspects, a detective on hand to investigate the murder. The structure feels traditional too: the set-up, the crime, the examination of evidence, the interviews with the suspects, more ruminations, more discoveries, more interviews, all culminating in a gathering in the dining car to deliver the truth.

The biggest complaint I hear from fellow mystery fans about MotOE is its Marsh-ian aspect of having to wallow through all those interviews. There are no less than thirteen suspects to consider here. (If one began his reading career with Carr, one would expect – what? four or five suspects at most?) The nature of her plot leaves Christie stuck with this large cast, but the pattern of summoning one passenger after another to the dining car for interrogation can seem stultifying to some. This issue is seemingly exacerbated by the fact that these characters are seemingly all strangers to each other, and the uncovering of secret relationships amongst members of the group necessitates further interviews of practically everybody.

To be honest, I’ve never been bothered by this aspect of the novel – and I assure you I can be as prone to “interview burnout” as the next fan. Christie parses out her information in expert fashion, and there is a lot of information to disseminate. The 1960’s Paperback edition’s back blurb called this “the case with too many clues”. Objects are dropped almost indiscriminately around the scene of the crime: the pipe cleaner, the stopped watch, the burnt letters, the lady’s handkerchief with an “H” stitched into it, the button from a conductor’s uniform. Then there’s the lady in the kimono, the mysterious “small, dark” gentleman in a Wagon Lit uniform, the grease spot on a Hungarian passport, and about ten significant verbal utterances! It was my second mystery, folks! I thought they all worked like this!

The Trick

The structure and the trappings may be traditional, but in the end, MotOE is as subversive as a mystery can get! Think of it, folks! My introduction to grown-up mystery fiction turned out to be two Agatha Christie mysteries where, in the first, everybody dies and in the second, everybody done it! If my next two choices had been The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and Crooked House, my mind would have been so sufficiently blown that I might have never recovered! Can you understand now why I can be so critical of other writers, why I approach the so-called Humdrums with an extra sense of caution, why I am enraged when a modern author’s work is described as “in the style of Agatha Christie” or when an author is hired to continue Christie’s legacy and is clearly ill prepared for that task? Through sheer luck, I have been royally spoiled, and it has colored my opinions for lo, these many years!

Christie was a master at manipulating her audience, taking us as far as she dared with a series of seeming coincidences that defy credulity, and she relied on our acceptance of the artificiality of GAD fiction to get us there. Of course it’s going to turn out that passengers knew Ratchett! Of course that list is going to grow exponentially as the investigation continues, until Bouc’s eyes are popping out of his head and Poirot is muttering, “This is extraordinary. They cannot all be in it!” I’m reading a modern mystery now where coincidence runs rampant to the point that I am figuratively throwing the book against a wall (I’m actually listening to it in my car, and it is affecting my driving!)

“And then, Messieurs, I saw light. They were all in it!” says Poirot.

I understand: I was twelve. It all seems so obvious to me now. But the thrill I got when I read those words and understood what Christie had done is almost indescribable. It’s the reason why I don’t ever like figuring out the ending to a mystery! That sense of being confounded is the most delicious feeling a mystery fan can feel, and nobody has made me feel it more often than Christie.

But let’s put the impact of that solution aside. Either you’re going to get it or you aren’t. Either you’re going to appreciate its cleverness or scoff at its artificiality. Your choice, buddy! There’s more to discuss here, since the ending is divided into two parts: the revelation of whodunit and the moral dilemma that follows. For Poirot has presented two potential solutions, and he leaves it to Bouc and Dr. Constantine to decide which he will present to the police. Which answer will leave us with the greater sense of Justice?

It seems to me that not for one moment in the novel does Poirot hesitate to push for the false theory that Ratchett was murdered by an unknown intruder. From the moment he rejects the murdered man’s proffer of taking on his case because “Frankly, Monsieur, I do not like your face,” Poirot has recognized Ratchett as the source of evil here. This is the detective’s gift: he sees Arlena Marshall as a pure victim rather than a seductress; he recognizes that Doctor Morley was not a cad who inspired murder but a good man in the wrong place at the wrong time; he understands the true nature of Mr. Alexander Bonaparte Cust and why John Cristow muttered “Henrietta” at the point of death. Poirot can read people. How else can he tell that a lady’s maid is actually a cook or that a travelling salesman would react so strongly to the sad tale of a French girl’s suicide? It’s only a matter of uncovering Ratchett’s true identity that seals the deal: justice was done before the case was solved. Poirot works that final scene with panache, ensuring that Bouc and Constantine will vote his way.

And so, Hercule Poirot allows thirteen people to get away with murder. And he does this so blithely that six books later he reveals this very truth to a witness in another case – brags about it in fact! Clearly, Poirot has no qualms about his decision. Justice was not served in the Daisy Armstrong case. Not only has that matter been rectified here, but one can see how deeply the sleuth appreciates the form that justice has taken, how carefully it was meted out to mirror what should have happened in the American courts. Each reader has to decide for himself if he agrees with Poirot, but Christie stacks the deck in his favor. To her, Ratchett’s death should signal the end of suffering – not the end of life – for all.

Over the course of forty-three years, four movie versions, two for the big screen and two on television, have tackled this story. Each adaptation’s approach to the murder itself is similar, but it is in that final question that they differ.

THE FILMS

The Albert Finney Version

Everything about the 1974 film version bespeaks class, from the elegant, understated direction by Sidney Lumet to the sumptuous design by Tony Walton and Jack Stephens. By 1974, America had been saturated with cheesy disaster movies like The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno, which were populated by “all star casts” consisting of great stars at the beginnings and ends of their career, with B-list actors firmly in the middle. There is nothing like that here, as Lumet gathered together one of the best ensemble casts since the MGM glory days of Grand Hotel and Dinner at Eight. For the most part, the actors fit the novel’s characters to a tee, so a few character name changes don’t really shatter the screenplay’s fidelity to the text. (Although why the Belgian Bouc had to become an Italian named Bianchi seems like a real shame.) Personally, Vanessa Redgrave and Sean Connery strike me as a little long in the tooth to play Mary and Armstrong, but that’s quibbling; Redgrave lends a quirky joie de vivre to her role, and Connery has never seemed so emotionally present. I especially love Wendy Hiller and Rachel Roberts as Princess Dragomiroff and Hildegarde Schmidt, and I don’t care how short a time Ingrid Bergman is onscreen or how much this has to do with America’s love affair with her, I think she deserved her Oscar for her heartbreaking (and funny) turn as Greta Ohlsson. The only false note for me was Anthony Perkins as Norman Ba – I mean, as Hector MacQueen. Considering how his role in Psycho essentially slaughtered Perkins’ career as a leading man, making him channel that mother-obsessed neurotic as Hector seems cruel and wrong.

The three major roles of Poirot, Mr. Ratchett/Casetti, and Mrs. Hubbard deserve more consideration in our discussions. Finney’s rendition of the sleuth has had a polarizing effect among Christie purists. I think this is largely due to the distracting amount of make-up used to transform the handsome actor into the egg-shaped Belgian, as well as Finney’s semi-comprehensible accent. Yet no one can say he doesn’t commit himself wholly to the role. He brilliantly renders what Poirot is like when he’s on the scent: the drive and passion for the truth, the outrage when he sees himself being played for a fool, the enjoyment of toying with suspects, particularly those he knows are lying to him, the interesting switches in technique as he figures out what will work best on each person to glean information.

Ultimately, I think that out of all the incarnations of Ratchett, Richard Widmark’s is the most successful. He fully captures the psychopath trying to operate as a banal businessman: the cold, dead eyes that belie any attempt at pleasantry, the casual bullying, the attempt to push away any sense of fear that opposing forces are closing in. One can understand why Poirot refuses this man’s request on the spot – Widmark oozes the crass superiority of a brutal man, whether he brandishes money or a gat in order to get his way!

I love Lauren Bacall. All she has to do is whistle – just put her lips together and blow – and I’ll come a’runnin’. But it’s impossible to buy her as Christie’s vision of “a stout, pleasant-faced, elderly woman who was talking in a slow clear monotone which showed no signs of pausing for breath or coming to a stop.” Bacall plays Mrs. Hubbard as Lauren Bacall playing Linda Arden playing Mrs. Hubbard, and something important is diminished in the process. She’s fun to watch, but she doesn’t possess Linda Arden’s ability to tamp down her inner diva and present herself as an ordinary American housewife.

I mentioned above that, knowing the solution, it can be hard to believe that any reader could be fooled by so obvious a climax. Screenwriter Anthony Shaffer doesn’t help matters by opening the film with an extended flashback, gorgeously rendered in sepia tones, of the Armstrong case. That information then sits there, undigested, until we reach the point where Poirot discovers the burnt threatening note: “ – member Daisy Arm – “ I guess that in terms of film structure, it’s a brilliant move that saves us a lot of time wasted on exposition, but it seems to me that it does a lot to give the game away even more quickly.

After the prologue, Lumet takes his time setting up the situation, introducing the characters and – most gratifying – making a character out of the train itself. This Orient Express is sumptuous, its movements gloriously scored by Richard Rodney Bennett. If, after the murder, the interviews begin to go on a little too long . . . and if the final accounting by Poirot stretches out just a bit more than it should . . . well, the film is so damn beautiful and reveals so much love and respect for the source material, that any longueurs can be forgiven in the end. It looks like a lot of money was poured in as well. The budget was a reasonable $1.4 million, and the box office take was $35.7 million. It was successful enough to inspire a run of classy (if increasingly campy) Christie film adaptations.

The Alfred Molina Version

You have to hand it to CBS: it was the first and only American television network to capitalize on Agatha Christie’s popularity. Between 1982 and 1986, CBS produced a half dozen adaptations of Christie novels, including three continuations of the Poirot film series that had starred Peter Ustinov. The deal – and I assume this had to do with saving money – was that the films would be set in modern day and would feature mostly television actors (although there were a number of high profile guest stars, such as Olivia de Havilland, Tony Curtis, and Faye Dunaway. The films were alright – not brilliantly written or acted but sufficiently faithful to the original novels to give this fan a little jolt.

And then everything sort of died away for a while. The big screen version of Appointment with Death was a flop, and producers moved on to other things. Then, in 2001, someone got the bright idea – and the rights – to remake MotOE as a vehicle for Alfred Molina as Poirot, with an all-star cast of . . . oh, who are we kidding? There’s one big star amongst the suspect list: Leslie Caron plays a Spanish noblewoman (the Princess Dragomiroff part – she was in love with a Russian dancer, who gave her a handkerchief as a gift!). A couple of TV celebrities of the day also popped up: Meredith Baxter (playing Mrs. Hubbard like Marilyn Monroe) and Peter Strause (playing Ratchett like Bugsy Malone); the rest of the cast were unknowns at the time . . . and stayed that way. (One wonders if their participation in this travesty was the death knell to their careers!)

Once more, the story is updated to the present, and the opening moments are hilarious. Poirot is again called to the Middle East to solve a case, but this time it’s at the behest of his unbelievably voluptuous on-again, off-again girlfriend, Vera Rossakoff. They have a fight, and Poirot storms off, runs into his friend Bouc (at least here he is a fellow Belgian), and ends up on a very cheap looking “luxury” train. There’s no snowstorm to cause the train to stop, just a paltry rockslide. But that’s the least of the ways this adaptation abuses the source material. For starters, the producers’ desire to save money meant casting fewer actors and eliminating the whole “jury of twelve” issue that was the crux of the novel’s solution.

Modern technology plays a significant part in this version: characters are seen talking on their cellphones, the pipe cleaner clue is replaced with a Blackberry stylus, and despite pining for the “good old days” Poirot cheerfully accesses information on a borrowed laptop. This is helpful since the plot drops the Lindburgh connection and makes Armstrong a Steve Jobs-like software guru. One has to ask why none of the many online videos of this famous figure that Poirot watches include ANY of the people on the train (aside from Arbuthnot, who in this version was Armstrong’s business partner). I mean, his mother-in-law was a famous actress, and the chauffeur has been replaced with a well-known physical fitness expert. Any decent search engine is going to give the lie to these characters’ stories. I guess there is a reason why GAD doesn’t work so well in modern fiction, given the immediate access to information that technology provides the police. There’s even a reference to the O.J. murder case, which evidently happened around the same time as the Armstrong murder, and we know how much video footage was recorded of that event!

Molina works hard to be a sensitive Poirot, if you can accept the detective as a 30-something ladies man! I admire Molina as an actor, but I feel like he underplayed the larger than life Poirot. The rest of the actors – even, alas, the lovely Leslie Caron – are totally forgettable. While this adaptation checks off the basic points of the novel’s plot, at a mere 80 minutes the whole thing feels both like a rush job and a bore.

The David Suchet Version

No one admires David Suchet’s mission to perform the entire Christie canon more than me, and for the most part I consider him the best incarnation of Poirot that we have seen. A lot of actors tire of a character after a while, but Suchet has gone on record numerous times about how much he loved the little Belgian. So it was gratifying that the Suchet version of MotOE was treated as something of a special event, even showing on Christmas Day in the UK.

A lot of love was clearly lavished on this episode, with location shooting in Malta, and a beautiful train set built at Pinewood Studios that, more than any other version, emphasized the claustrophobic atmosphere of this mode of transport. The cast is comprised of excellent actors, including Toby Jones as Ratchett, the always brilliant Eileen Atkins as Princess Dragomiroff, Hugh Bonneville as Masterman, the valet, and two fine American actresses: Barbara Hershey as Mrs. Hubbard and Jessica Chastain (who the following year would take the U.S. by storm with her performance in The Help) as Mary Debenham.

What does one say upon watching the Suchet version of MotOE? From the very start, one realizes that big ideas are at work! It could have been the work of David Suchet, who had demanded that the spiritual side of Poirot be explored. It could have been screenwriter Stewart Harcourt who, the previous year, had adapted The Clocks (and done nothing right with it) and who would go on to pen the execrable By the Pricking of My Thumbs for the new Marple series. (Tuppence Beresford as an unhappily married alcoholic . . . that’s plumbing the hidden depths of Agatha Christie for you!) Whatever the case, it’s clear from the start that in this version, the story has to stand behind an approach to tone and theme that is numbingly dark.

Once again, Poirot is in the Middle East, handling a matter of some delicacy for the French military. His zealous pursuit of justice (a word that I think I counted being said around 43 times in the first 15 minutes of the program) is put on pause when the accused soldier grabs a gun and blows his own brains out. Poirot defends his actions in the cause of Justice, deriding the cowardice of a man who would take the easy way out instead of facing the music like a man. But it’s all talk: you can see in Suchet’s posture that this odd version of Poirot is suffering the pangs of guilt and indecision.

Cut to a scene on the streets of Istanbul where Poirot spots Arbuthnot and Mary Debenham having their secret exchange. This time, they are interrupted by a desperate woman who is being chased down by a mob. It turns out she is an adulteress, and despite attempts by Arbuthnot to help her, she is dragged into a public square and stoned to death. Poirot does nothing to intervene, and later, he defends his lack of action as a decision to not interfere with this local dispensation of “justice”, arguing with Mary that it is not his or her right to judge the brutal methods of a culture or one’s disagreement with the local laws.

Thus, the first murder is of the audience, who is bludgeoned to death with Significant Thematic Events!! Here are Mary and Arbuthnot reeling with horror at local citizens taking the law into their own hands, something Mary and Arbuthnot are on their way to do!! Here is Poirot, refusing to judge these same citizens, something he is set to do shortly on the Orient Express to his fellow witnesses!!! Oh, the irony! Oh, the pain!

Where the heck is Poirot, that charming, funny man, and who replaced him with this stiff, sour symbol of Truth. Playing that part this time around must be a heavy burden for Suchet: he looks ill throughout this episode, he snaps at everyone and prays feverishly when alone, and he provides not a drop of wit or warmth from beginning to end. When he rejects Ratchett’s plea for help, he appears half drunk at the bar and looks like he’d like to kill the man himself. And yet, when Ratchett is murdered, Poirot heaves a sigh and, as if by an instinct he now finds distasteful, takes charge of the investigation. Justice for Ratchett is now his responsibility, and he will see the task through no matter what!

No group of excellent actors or fine scenic design can save this drab and dreary affair. I have to admit that the first time I saw it I stepped back and asked myself, “Is this an interesting question: would Poirot have been troubled by his decision not to tell the police the truth?” I half-convinced myself that it was. But that is not what happens in the novel, and there is really no basis in Christie’s entire canon to think Poirot would question his own actions or find them at odds with his Catholic beliefs. It was almost impossible to watch this one a second time.

And listen: I admit I’m something of a purist, but I honestly believe that it’s okay to explore ideas in someone else’s work, even if this exploration might cause an adaptation to diverge from the source material. It’s interesting to suppose that Philip Blake might have despised Caroline Crale because he loved her husband rather than the woman herself. A man as empty of warmth as Blake could easily have become that way by stunting his true romantic nature. And remember that cocaine binge in the latest version of And Then There Were None? Are ten people trapped on an island who have all murdered before and are now being murdered themselves really going to behave like proper ladies and gentlemen? Okay, sometimes these ideas work, sometimes they don’t. But neither example I offer here sent the teleplay into collapse. Turning the murderous couple in A Body in the Library into lesbians was stupid and did nothing for the adaptation, but neither did it prevent the plot from basically unspooling as it did in the novel.

Unfortunately, Suchet’s MotOE runs right off the rails. At least Barbara Hershey’s Mrs. Hubbard isn’t played for glamor, but neither is she a “typical American tourist.” I understand that a group of modern writers might sit in the common room and ask themselves how a group of people would really feel if they were gathered to execute someone. I fully acknowledge that if I were about to set off with several of my friends to murder someone, my stomach would be tied in knots. I wouldn’t be able to touch the vichyssoise. But when it comes time to show the murder in retrospect, these passengers are just as convinced of the rightness of their action as those in the other adaptations and in the book. This time, it’s Poirot who gums up the works. He presents his two theories but advocates telling the truth. Bouc disagrees with him. The passengers plead with him. They attack his faith. They threaten his life. Everything they do obviates their sense of righteousness and essentially topples Christie’s original belief about justice as presented in the novel. And although ultimately, Poirot lets them go free by his own choosing, that choice tears him apart. He walks away a broken man.

What a delicious set of emotions it must have been for an actor to be allowed to play! And how thoroughly wrong it is, how badly it damages our experience of watching this adaptation. What a shame . . .

The Kenneth Branagh Version

Okay, enough with the stalling – we all know why I’m really here! I come to bury Branagh, not to praise him. I come to ridicule his moustache, to rail against the concept of Hercule Poirot, Action Hero ™, to go on a tirade about Johnny Depp, and to once and for all blast the idea that we needed yet another remake of Murder on the Orient Express in the first place!

There’s just one problem . . . I really loved this movie.

Holy cow, folks, I did not expect to feel this way. But I have to tell you that Branagh has delivered a film that is true to the spirit of the novel and the period and yet brings something that is ineffably modern – but never forced – in its approach to the material. The best way I can describe it is that although the story is definitely set in the appropriate time period (1934), it never feels fustily wrapped in nostalgia. The screenplay by Michael Green (who is known for action movies, like Logan and Blade Runner 2049) creates a sense of immediacy in the chain of events, and I have to say that if I had never read the book before, this is the one adaptation that might have tricked me. Even as we slowly learn of the connection between passengers to the Armstrong case, other options are weighed, and suspicion is legitimately passed around between suspects, something that quite frankly I don’t remember even feeling in the book. MacQueen is stealing from his boss, Masterman is dying and feels no compunction to talk back to his cruel employer. And in a lovely bit of mischief, Mrs. Hubbard has a moment with Ratchett that reminds us that this is a man and a woman before us, and we have several days of train travel to fill before we reach our destination.

The movie is beautifully filmed, and although we do get to spend lots of time on a fabulously appointed train (one that does not feel claustrophobic due to all the big windows – a quality I would imagine a luxury train to have), we also get a sense of the world through which Poirot and Company are traveling. From its starting point in Jerusalem through the Balkan mountain range, Branagh finds ways to let us breathe and not feel trapped in the stultifying atmosphere of a single set.

There is not a false note in the acting. Even the ludicrous moustache on Branagh fades from our minds as we take in his version of Poirot: slightly younger, it is true, funny without being a figure of fun, and haunted by the loneliness that being the best seeker of justice in the world can make a man. Yes, he runs and jumps a bit, but he isn’t playing James Bond here, just ratcheting up the physicality of the character a little. Is it wrong? Sure. Did it bother me? I was surprised at how little it did. Johnny Depp pulls back the histrionics to deliver a fascinating portrait of an evil man running scared but still enjoying the fruits of his crime.

Why make Colonel Arbuthnot a black doctor? Why have Cyrus Hardman disguise himself as an incipient Fascist instead of a traveling salesman? Why make Count Andrenyi a ballet dancer? All I can say is that these choices allow Branagh to bring these characters to life as part of the times in which they lived, making reference to social issues that, in my opinion, served to deepen the characters rather than distract from the story. M. Bouc is made young, the son of one of Poirot’s friends, and we watch how events transform him from a callow rich boy to a man of responsibility.

Meanwhile, the characters who stay true to the original novel are all heartbreaking: Judi Dench’s Princess Dragomiroff, Josh Gad’s Hector MacQueen (Gad is a very funny fellow, and he erases all his comic instinct to create this character), and most of all Derek Jacobi as Masterman. And if Mrs. Hubbard has been written to stick to the filmic tendency of an attractive divorcee rather than a homely widow, no other actress who has assayed the role has managed to show this woman’s transformation and her tragedy as brilliantly as Michelle Pfeiffer does.

Branagh finds a way to make the final summing up exciting and moving. This film does explore the concepts of justice and conscience, of the price one pays to take the law into one’s hands. Branagh’s Poirot is troubled by his final decision, but we also see the genuine compassion of the man, not only because he has weighed the scales and considered that a form of justice has been done, but because he worries about how these people will deal with their act. Branagh starts the film with a twinkle in Poirot’s eye, and he has the grace to bring that twinkle back at the end without negating the weight of what has gone on before.

When I was twelve, I got to the final pages of this book and dropped it on the floor in profound surprise at its revelation. It became the moment by which I measured the success or failure of every other mystery I ever read. And although this set the bar impossibly high, I have clearly experienced much joy in the passing years from the mysteries I’ve read. Watching the latest film, my heart grew full at the idea that, fifty years later, Murder on the Orient Express still has the power to surprise me. I’m grateful to Branagh and Company for pushing that button, and I salute Agatha Christie for setting the train in motion in the first place.

You know, Brad, that book had a profound effect on me, too, so I can completely understand your feeling about it. I have to admit, too, that the closer a filmed version stays to the original story, the better. That’s why I like Suchet best as Poirot, but not that version of the novel, if that makes sense. And as star-studded as the version with Albert Finney was, it diverged too much from the book. Just as one example, Lauren Bacall (fabulous as she was as an actress) was not the Mrs. Hubbard of the book, if that makes any sense.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s exactly how I feel about Bacall, too, Margot. There was much to like about the Albert Finney version, so it comes as a tremendous surprise to me that the Branagh version is my favorite, despite some changes!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This piece was touching because of the reminiscences, entertaining in style, and informative in its critique. Excellent! Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, Christophe!

LikeLike

Fantastic and complete article. Yesterday, I watched MoTOE, the latest Kenneth Branagh version. I found it entertaining, and enjoyable. Although this version of Poirot was a more energetic man physically, his emotional depth for me was missing – the true anguish of his dilemma of balancing justice within the law as opposed to calculated vengeance however justified seemed rushed at the end. I suspect you will disagree here – but where was his anger and outbursts at the group.

The reveal of Mrs Hubbard/Linda Arden as the grandmother could have been given more prominence as it seemed, for me, to be quickly brushed over.

Katherine – Poirot’s relationship, having not read the book I didn’t catch the relevance to the plot.

I did enjoy the many subtle clues and metaphors, for example, Mrs Hubbard looking for a man, and Poirot insisting that all things should balance – equally sized eggs and equal measure of the manure on the shoes.

Your experiences with the additional information from your story has brought extra quality to my experience of watching the film.

Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you, James. I agree that the ending was a little rushed, but if you have seen the 1974 version the ending goes on and on and on . . .

Regarding Poirot’s anger, none of that exists in the book. It was there in spades in the David Suchet movie, and in my opinion it caused that version to topple. I didn’t bring up the Catherine issue because it is not in keeping with Poirot’s character, it is not in the book, and I thought it best to simply ignore it. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great write-up. Brad! I’m looking forward to seeing the Branagh film, but not sure when it hits Colombo cinemas before January.

Have you heard the BBC radio version with John Moffatt? Faithful to the original; top drawer British actors and actresses, including (and I quote from the BBC):

Siân Phillips as Princess Dragmiroff, Francesca Annis as Miss Debenham, Joss Ackland as Mr Ratchett, Frank Windsor as Pierre Michel, Sylvia Syms as Mrs Hubbard, and Desmond Llewelyn as Masterman.

Moffatt may well be the best Poirot of them all, because he plays /Christie’s/ Poirot, in all his wisdom and compassion.

LikeLike

Thanks, Nick. I was tempted to include the radio version here because it is wonderful. I have all the BBC broadcasts, and I enjoy them over and over again in my car. But I figured I was going long, and I want to talk about the radio shows in and of themselves some other time.

LikeLike

Congratulations on 200 posts, Brad, and thanks for this rundown — oh my fur and whiskers, that Molina version was terrible. I remember the Finney version (and the Ustinov Death on the Nile) being on TV soon after I’d started reading Christie, and in both cases I struggled so much with the representation of the dapper, demure, pompous little Belgian as this larger-than-life scenery chewer that I didn’t get much past 15 minutes in. The Molina version was just…weird. He seems asleep half the time. Mind you, everyone seems a sleep half the time. Maybe it was a warm set.

I have seen startlingly little Suchet-as-Poirot. Oh, I know it’s the definitive protrayal but I have a sneaking suspicion — hear me out — that it’s simply because he’s done it for a long time and everyone has gotten used to how he plays it. Maybe one day soon I’ll sit down and watch a whole one and love it (I probably won’t — watch one, I mean). but from mempry he’s not what I got from the books. Weird how the mind works, innit?

As for Ken-Ken…I’m curious, and I welcome a fresh take from an established actor and director, but I just wish that this hadn’t been what they’d used to po(iro)tentially launch a new series. Yes, the setting allows for stunning locations, and grand Acting, but I’d love to see some of Christie’s less-heralded plots get the public acclaim they deserve. I have a sinking feeling, though, that if this is successful enough to jusfity a sequel it’ll be Death on the Nile agian (locations! Acting!), no-one will care all that much, and the whole enterprise will grind to a halt there.

I have, however, been guilty of pessimism before, so who knows…?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Who’s the best Batman? Who’s the best Holmes? You’ll never get me to argue about Suchet or any other actor in a much-played role because it’s all so personal. (I love Basil Rathbone’s Holmes, and even if Jeremy Brett was “better” it has to do with growing up with the films. Heck, I love Nigel Bruce as Watson, and I absolutely understand why this is the wrong thing to do! Bad Bradley! Bad!!).

But I am right behind your point about the blind eye Hollywood has turned to the “minor” stories. This is why the announcement of Kenny’s MotOE filled me with ennui (any why I’m so pleasantly surprised how much I liked it . . . and I’m ALWAYS a big enough man to admit my mistakes!) and why I jumped up and down over the announcement of Crooked House. I don’t think we’ll ever see big screen adaptations of the “local” Christies. The Mirror Crack’d was the only village mystery I can recall being produced, and it bombed. This might be another reason that Carr isn’t produced. Maybe Nine, and Death Makes Ten would have some possibilities . . . if they added a thread from a German U-Boat.

But maybe if Crooked House succeeds, we’ll see Sad Cypress or Peril at End House with big stars! I’ll be right there if it happens! (Even for They Came to Baghdad!!!)

LikeLike

I much like Suchet’s version of Peril At End House and that’s as about perfect and faithful an adaptation as The ABC Murders. I would much rather see stories that haven’t been done such as They Came To Baghdad or Destination Unknown. But what concerns me is if these stories were done on the big screen, in order to appeal to 21st viewers, they will make it so action-packed with explosions and shooting scenes, like many of today’s action-genre films.

LikeLiked by 2 people

An insightful and personal take on a classic. And how I agree with you on the Suchet version. A Poirot warped by the makers’ personal agenda – or possibly severe indigestion – and more grimness than in an Eastenders Christmas omnibus.

LikeLiked by 1 person

>>>I think we all know that Christie embraced the legal system and the idea of capital punishment with great fervor. In 4:50 From Paddington, after Miss Marple has captured a killer, she expresses with little old lady-like vehemence her disgust that a change in law will rob the community of a good hanging.<<<

"I am really very, very sorry that they have abolished capital punishment because I do feel that if there is anyone who ought to hang, it's ———-." This is Miss Marple speaking, not Christie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Too much mercy often results in further crimes which are fatal to victims who need not have been victims if justice had been put first and mercy second.”

That’s Agatha Christie talking.

Her characters all had differing opinions, so I should know better than to consider any of them a mouthpiece for the author. Doctor Haydock in Murder at the Vicarage equates criminal behavior with sickness. On the one hand, he believes that someday all criminals will be “cured.” Until then, he advocates:

“Shut up these people where they can’t do any harm—even put them peacefully out of the way—yes, I’d go as far as that. But don’t call it punishment. Don’t bring shame on them and their innocent families.”

It does seem to be the running theme when Christie’s characters talk about justice. And I say this as someone who is vehemently opposed to capital punishment, so I’m not hoping that Christie believes in this.But when character after character expresses this same opinion, it’s hard to resist coming to a conclusion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t think I’ve ever seen the Molina version, but I noted that the missing characters are Hildegarde Schmidt and Greta Ohlsson, two female characters who are much more interesting than some of the male characters who were retained. I like the way the new version conflates Dr. Constantine and Col. Arbuthnut. That’s a clever adaptation trick and a wise solution to reducing superfluous characters for budgetting purposes.

Of interest to you as an English and theater teacher: There is yet *another* version that I only just learned of. Ken Ludwig, known for his mega hit farce LEND ME A TENOR, wrote an adaptation and reduced the cast to nine suspects, Poirot and Bouc while also adding a prologue featuring the story of the kidnapping. There is a part for Daisy! Why bother? The world premiere was at the McCarter Theater in Princeton last year. I’ve not found any reviews that were hypercritical though some were tepid. I’m very much interested in finding a copy of the script to read.

LikeLike

Me, too! And Kevin Elyot’s Hyper-violent version of And Then there Were None!

LikeLike

Horrible way to spoil a book for those who have not read it yet. You could have easily redacted the name. I’m surprised Brad hasn’t edited the comment to remove that spoiler.

LikeLike

Just saw your comment and put two and two together, John. I’ve edited the name out of her comment.

LikeLike

Phew! Got to the end of your mammoth post to discover were are pretty much in perfect sync on everything! Which is a really nice feeling! Great post Brad, bravo!

LikeLike

Thanks, Sergio! I waited to read your review until after I posted my own. I also loved Olivia Colman (I always do) and Daisy Ridley. The characters mattered in this version more than in 1974. I won’t try and convince other hard liners – heck, I can be just as hard about some things. But I look forward to seeing this one again! (And I can’t WAIT for Crooked House!!!!! 🙂

LikeLike

You did an excellent overview chum, reallyvfirst rate. Not just saying that because I agree 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Possible spoilers about the movie ahead….

Lovely post, Brad. I also enjoyed the movie overall–more than I thought I might (though I still have quibbles). As you mention, the mustache was less distracting than anticipated (after seeing the trailer I was afraid the dead ferret might come to life and crawl off the screen). Speaking of the mustache, I noticed that while they set him up with a mustache-preserving contraption the first night that they didn’t bother with it the night of the murder. I can’t imagine our order and method conscious Poirot forgetting to care for his mustache….

I did enjoy the very lush visuals of the train and the scenery and appreciated that they kept it in period. I’m a purist when it comes to filming vintage mysteries in period and get distracted when they modernize. The two big problems for me are 1. making Poirot into a bit of an action hero (a la Robert Downey, Jr as Holmes–though not quite so much) and 2. Poirot’s moral struggle with the solutions at the end.

The sub-problem with number one is that they do go to great trouble to bring out the fussy, dandified elements of Poirot (immaculate shoes, must have eggs the same size, etc) and then expect us to believe that this fussy man is going to go chasing suspects on train trestles. I did enjoy the clever action-hero bit at the beginning though (when he shoves his stick into the wall). That was a good bit of action that relied on the little grey cells anticipating the culprit’s movements instead of chasing people around in the snow.

Item 2 follows in the vein of Suchet’s agonizing over right and wrong in his version–but tones it down. This would be my biggest, maybe only, quibble with Suchet’s Poirot in MotOE–it’s not true to Christie’s character who in the book says only that he is in two minds about the solution, but never has great agonies over lying to the police about the solution they decide to provide or, in Branagh’s portrayal, dramatizing his dedication to the truth by saying somebody would have to shoot him to prevent him from giving the correct solution to the police.

LikeLiked by 1 person

SPOILERS AHEAD! DON’T READ IF YOU HAVEN’T READ THE BOOK OR SEEN THE MOVIE!

” . . .in Branagh’s portrayal, dramatizing his dedication to the truth by saying somebody would have to shoot him to prevent him from giving the correct solution to the police.”

I don’t know if this was the intention, Bev, but I kind of thought this was a trap on Poirot’s part to see what they would do. There were no bullets in the gun, and Mrs. Hubbard ends up pointing the gun at herself. I thought that might have been the straw that proved to Poirot that these were all good people. The people in the Suchet version actually toyed with killing Poirot and worse! they insulted his faith.

LikeLike

very true on the Suchet version–I really don’t like that ending, so Branagh’s take is better. I’ve actually been processing this more (with the help of another friend’s FB thread. I may have to see it again, because the longer it percolates the better I like it.

LikeLike

Just saw the new film starring Kenneth Branagh. I give it 2 out of 5 stars. Still prefer the book THEN the 1974 version which is still the best adaptation of the book, despite some of its flaws

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post and I agree with your reviews of the two versions I have seen which makes me hopeful for the Branagh whenever I make it to the theaters.

Have you heard the new Audible radio adaptation with Tom Conti yet?

LikeLike

I have not. I don’t have Audible.Is it good? I know Conti is a great actor.

LikeLike

I have only got part-way through the audiobook but I am enjoying it so far. It is considerably longer than the Moffatt version and has some narration (from Art Malik!), though it is cut down from the novel.

So far I’m enjoying Conti’s performance though I empathize with some of the reviews that suggest he can be a little hard to understand. He speaks quite softly at times and it took me a little while to get used to it.

LikeLike

I felt the middle of the film was disjointed, spliced with ridiculous action-scenes and the interviews felt short and rushed. If only the beginning was cut, and middle scenes like the “Katherine” angle, Poirot’s inner struggle, and ridiculous action sequences and more attention was placed on the interviews/interrogations themselves along with a longer film running time, I feel like the pay off clearly would have been more powerful. One complaint about the film that I’ve heard was many viewers didn’t feel they were involved in the solving of the mystery; the clues weren’t all there and they felt cheated. To get to that big payoff, you have to keep the viewers involved and invested in the mystery. I found the ending powerful and it could be because I already know the conclusion (which I always found powerful) and on top of that the music in that scene moved me. But the middle was so crammed together with too many things, I can see how viewers lost interest and if they lose interest, how can they feel the power of the ending? You lost them way before the mystery’s solution. More emphasis should have been on the clues and interviews themselves. That’s the key to a mystery. That’s the key to keep an audience interested whenever a mystery is adapted onscreen. And screenwriters and directors, you can still film it in such a way for a 21st century audience that won’t bore or deter them if that’s something you’re worried about when filming a true whodunit. Because great visuals and cinematography just isn’t enough for a mystery.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“More emphasis should have been on the clues and interviews themselves . . .That’s the key to keep an audience interested whenever a mystery is adapted onscreen.”

With all due respect, Brian, I couldn’t disagree more. Film is a visual, rather than a verbal, medium, and those interviews, while necessary, cannot be excessively long, nor can they be visually static as they are in a book where the detective is looking at a suspect’s eyes and hands, and listening to their tone of voice. As I mentioned, MotOE is teeming with clues, and the film got most of them. If I also feel the mechanics of the mystery were rushed, well, I’m a fervent classic mystery fan. Many of the books I read are chock full of archaic sounding language, but I get through that in order to enjoy the puzzles. One of my students told me the theatre as “jammed” the night he saw it, and I guarantee you that 90% of that audience has not read GAD. They came for the excitement, and the film delivered. It also gave me a lot of what I enjoy about the novel. Cut the “Catherine” part, sure, but I never lost interest, and as a devoted Christie fan, I would be the first to admit if I did.

LikeLike

But Brad, that’s why I said, “Screenwriters and directors, you can still film it in such a way for a 21st century audience that won’t bore or deter them if that’s something you’re worried about when filming a true whodunit.” I felt that the interviews/interrogations in the 1974 version weren’t long but went at a good pace and im my opinion far from boring, but I guess it’s because I’m a mystery fan. Today, many would find that version boring and slow but I think that has more to do with the times and trends in films today where the pace has to be speed on a bit faster than yesteryear.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I may be the only hardcore Christie fan who prefers Finney’s Poirot over all of them. I loved Suchet as well, just not as much. The Molina version I like to tell myself, was just a nightmare of mine. As for this new version, being a purist, I despise variation from the original, changes to characters and the insertion of inappropriate issues into stories where they don’t belong.

Slice it, dice it, mince it, chop it, but a black Cuban doctor is not going to travel on the OE in 1935. Further, he isn’t going to be entangled openly with a white woman. This is just a silly social agenda inappropriate and unbelievable for the times. Moreover, why make the change? Why change the races and stations of the passengers? Their backstories? GAH

Because the writer felt that a train full of white Europeans was too racist? LOL. It was the way it was. Trying to rewrite history to reflect our more “tolerant” and “aware” times, particularly, using someone else’s (then) contemporary mystery story to do it — Blech! Feh!

I am also unable to disregard the carpet remnants. Sorry, I just can’t.

Exceptionally great post Brad, about one of my favorite stories ever.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes you did overlook one very exceptional version of the story. It’s Japanese and names have been changed. But the story continues to provide a backstory for the murder. I think you and your readers would enjoy this immensely.

http://dramacool.es/orient-kyuukou-satsujin-jiken-episode-1.html

LikeLike

Thanks for the link, marblex! I HAD heard of this one but hadn’t seen it. I had heard that it takes a rather comical tone, and from watching the first ten minutes, I would say that this is true in terms of the Poirot figure and the music. Watching a very traditional version of this luxurious story unfold from a different cultural perspective is fascinating! Thanks again!

Oh, and I won’t try to convince you about Branagh’s version, but I wanted to point out that you merged the black doctor and the Cuban car dealer. I read an interview with Branagh. He wanted a more diverse cast in keeping with the wonderfully diverse range of actors available today. He researched and found that both characters could have existed. Whether they could have afforded riding the Orient Express was not something I paid much attention to. They WERE both in second class compartments. I don’t think Luigi Foscarelli or Cyrus Hardman could have afforded the best tickets either.

And I can’t for the life of me recall “the carpet remnants.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I may have mixed up the characters a bit but my point remains. These people wouldn’t have even been in “steerage” in that time period on the OE.. “Diversity” within society is a very modern concept and was not a “thing” in the PostWWI through WWII Europe.

It’s the stash… I can’t get over it at all… it’s too ludicrous and it moves every time he speaks. GAH

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh and don’t forget to watch Part II of the Japanese version, it is truly unique.

LikeLike

I’m shocked. A modern adaption of something, actually good? I’ll have to wait till a friend of mine decides to get it so I can see it then. (Yes, I’m that much of a moocher.)

I’m also dismayed because I’ve *technically* been blogging for like two years and I’ve barely broke ten posts. Now less, because Blogger seemed to read “I would like to add tags and tweak this image” as “Delete the whole post.” Ugh.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Murder on the Orient Express (Movie) – Mysteries Ahoy!

What I found wrong about the Branagh version-which I, on the whole loved-was that it failed to get two key points into the script:

1) That Cassetti was already tried and sentenced to death and had only escaped through trickery and

2) That Cassetti was not a one time opportunist, but a serial kidnapper/killer who had taken and killed other children before Daisy and might very well do it again in the future.

Without these two key points, the moral question is much more black and white. It becomes much harder to justify or excuse the murderers. What they have performed is NOT, as in the novel, carrying out the decision of a court of law, and cannot be said with any conviction to be to prevent future crimes. It’s pure vigilante justice. Thus, there should be NO chance that someone with as rigid a sense of law and order as Poirot would ever excuse this, or that the audience can either. I cannot decide if the writers actually wanted to make the moral question more black and white (why?) or if it was simple ignorance on their parts.

But, as I said, on the whole I loved it. I am the Christie fan who thinks that the criticism often lobbed at Roger Ackroyd-that the mystery is not that interesting and it’s only famous for it’s twist ending-should be applied to MOTOE. I do find the excessive interviewing in the book and especially the 1974 film, tedious and slow, I thought the new version stayed true to the original spirit, while doing a LOT to liven up the story and keep things moving. And the cinematography was magnificent.

LikeLike

I honestly do not remember this aspect of Casetti – and I don’t recall it being included in any of other adaptations either. Certainly, the Suchet version wants you to grapple – and grapple hard – with the murderers’ vigilantism. That group keeps compounding their sin with more and more terrible decisions.

What I loved about the Branagh version was that, for the first time, you saw how utterly awful it was for these people to kill – even so loathsome a man as Casetti.

LikeLike

I don’t think that it was included in any of the adaptions. In fact, in the Finney version Casetti was never caught. But in the book he was caught and trialed and got away by means of blackmail and bribery. That was one the reason why the passengers killed him, because he couldn’t be trialed again.

LikeLike

Pingback: Murder on the Orient Express (1934) by Agatha Christie – Dead Yesterday

Pingback: A CENTURY OF AGATHA CHRISTIE, PART TWO: The Glittering 1930’s | ahsweetmysteryblog

Pingback: Murder on the Orient Express by Agatha Christie – Mysteries Ahoy!

Pingback: A HUNDRED YEARS OF CHRISTIE: Requiem and Rebirth in the 70’s | ahsweetmysteryblog

Pingback: A HUNDRED YEARS OF CHRISTIE. FINAL CHAPTER: The Millennium and Beyond | ahsweetmysteryblog

Pingback: MY AGATHA CHRISTIE INDEX (The Blog-iography!) | Ah Sweet Mystery!